Case Report

Vascular Mirage: When Sarcoidosis Conjures a Spontaneous Pseudoaneurysm in the Superficial Femoral Artery

1Department of Medicine Shifa college of Medicine, Islamabad, Pakistan.

2Department of Rheumatology, Shifa International Hospital Islamabad, Islamabad, Pakistan.

3Department of Histopathology, Shifa International Hospital Islamabad, Islamabad, Pakistan.

*Corresponding Author: Asim Mehmood, Department of Medicine Shifa college of Medicine, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Citation: Mehmood A, Rida, Ullah Z, Mamoon N. (2024). Vascular Mirage: When Sarcoidosis Conjures a Spontaneous Pseudoaneurysm in the Superficial Femoral Artery, Clinical Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia publishers. 2(2):1-4. DOI: 10.59657/ 2995-6064.brs.24.017

Copyright: © 2024 Asim Mehmood, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: November 18, 2023 | Accepted: January 18, 2024 | Published: January 24, 2024

Abstract

A pseudoaneurysm is a pulsating, encapsulated hematoma that communicates with a damaged vessel. It can develop either iatrogenically or spontaneously. In both cases, it is a cause for major concern because it can rupture, bleed, or potentially lead to sudden death. In this case report, we present the development of a pseudoaneurysm in the Superficial Femoral Artery (SFA) of a 51-year-old male patient with sarcoidosis. It is relatively uncommon for pseudoaneurysms to arise spontaneously, particularly in patients with sarcoidosis. Early diagnosis and timely intervention are critical in preventing potentially life-threatening complications associated with pseudoaneurysms. The successful management of this case underscores the effectiveness of these treatments in addressing vascular anomalies, ensuring the patient's well-being, and minimizing the risk of complications.

Keywords: vascular mirage; sarcoidosis conjures; pseudoaneurysm; superficial femoral artery

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous illness that often affects the pulmonary system, as well as other organs such as the eyes, skin, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Its clinical signs are nonspecific. Sarcoidosis typically presents with erythema nodosum, weight loss, fatigue, a persistent dry cough, and eye and skin symptoms [1]. It is an inflammatory granulomatous illness that can affect any organ and is estimated to impact 2 to 160 individuals per 100,000 people worldwide. Approximately 10% to 30% of sarcoidosis patients progress to develop a chronic lung condition. The 5-year follow-up period is associated with a mortality rate of about 7%. Pulmonary sarcoidosis, especially the severe form, accounts for more than 60% of fatalities [2]. In this context, our attention is drawn to the pseudoaneurysm of the SFA, which formed without any evident predisposing factors or femoral fracture resulting from forceful trauma. These are localized vascular enlargements that can develop spontaneously or as a consequence of medical interventions. They arise due to arterial wall ruptures and controlled bleeding [3]. The etiology of pseudoaneurysm in the context of sarcoidosis remains poorly understood and requires further investigation. Fortunately, advances in endovascular repair techniques have expanded the range of treatment options, encompassing conservative approaches to surgical interventions.

Case Presentation

A 51-year-old male patient presented to the outpatient department with a complaint of right inner thigh swelling persisting for the past 2 months. The swelling was characterized as painful and pulsatile, although non-tender, and was not linked to any traumatic incident. The patient exhibited no skin lesions or swellings on other areas of the body. Additionally, he did not report experiencing dizziness, weakness, or fatigue. His medical history revealed hypertension for the past 6 years and a known case of gout, with the presence of small non-obstructive uric acid calculi in the right renal system. Upon examination, his blood pressure measured at 140/80 mm/Hg, with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. His pulse rate was recorded at 78 beats per minute. Local examination unveiled an expanding, pulsatile lump measuring 4 × 4 cm, which was palpable on the upper inner side of the right thigh, approximately 6 cm below the inguinal ligament. A bruit was auscultated over the femoral artery. Swelling of the right calf was evident compared to the left side, and distal pulses on the right were weak but palpable. The temperature was consistent on both sides. Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) was requested, revealing the presence of a pseudoaneurysm in the superficial femoral artery. Laboratory tests demonstrated normocytic normochromic anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 12.2 g/dL (normal range for males: 13.5-18.0 g/dL). C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels were elevated to 20.23 mg/L (normal range up to 5 mg/L), and the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) was increased to 87 mm/h (normal range: 0-20 mm/h).

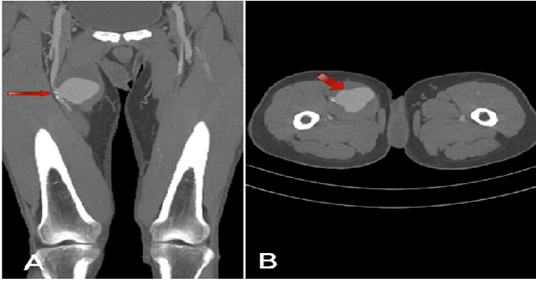

Figure 1: CT scan: Coronal view (A) and axial view (B).

Saccular aneurysm along the right proximal SFA measures 6.1 × 6.4 cm (anteroposterior × craniocaudally) and exhibits an irregular circumferential partial thrombus. It is situated approximately 8 cm from the right hip joint. A workup for vasculitis was initiated due to the suspicion of Takayasu's Arteritis (TA). The patient was also commenced on medications for presumed TA, which included deltacortil (5mg) and azathioprine (50mg). During this period, the patient developed bilateral (left > right) axillary lymphadenopathy. Positron Emission Tomography and Computed Tomography (PET-CT) revealed multiple nodes with avid uptake, with the largest measuring 1.3 cm in the left axilla. Under local anesthesia, an ultrasound-guided left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed, and the specimen indicated a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. No evidence of vasculitis or malignancy was observed in the examined sections, and Tissue Culture/Sensitivity (C/S) also yielded negative results for Acid Fast Bacilli.

Figure 2: Axillary lymph node biopsy.

A: Cores of nodal tissue showing round, non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas (H/E 4× obj).

B: Well-formed epithelioid granuloma surrounded by multinucleated giant cells (H/E 20 × obj).

Based on the findings of the biopsy, a diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established. Methotrexate was subsequently incorporated into his ongoing treatment regimen. The patient underwent surgical management for the pseudoaneurysm of the SFA, involving the excision of the aneurysmal SFA segment and evacuation of the aneurysmal cavity. This was followed by an above-knee femoral-popliteal bypass using a synthetic graft, all performed under general anesthesia. Biopsy of the excised specimen yielded two distinct parts. The first part, labeled as the aneurysmal wall, measured 1.0 × 1.0 × 0.7 cm and revealed fibro-collagenous cyst-like tissue with chronic inflammation and hemosiderin deposits in the wall. The second part, labeled as the arterial wall, measured 1.3 × 0.7 cm and exhibited mild intimal myxoid changes and foci of dystrophic calcifications in the wall. Tissue culture and sensitivity (C/S) showed occasional pus cells, with no growth observed after 48 hours of incubation. Post-surgery, the patient received prophylactic antibiotics to prevent surgical site wound infections, and his previously prescribed medications for sarcoidosis were continued. He was discharged from the hospital after a 2-day stay. A follow-up appointment one week later revealed a healthy wound, with palpable distal pulses.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that often affects the pulmonary system as well as various other organs, such as the eyes, skin, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Clinical symptoms are typically nonspecific. Most commonly, symptoms such as coughing, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, dyspnea, and low-grade fever are mild and non-specific. Systemic symptoms like fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats are also typical, while hemoptysis is a rare occurrence [4]. Sarcoidosis can manifest as acute, subacute, or chronic, with many cases remaining asymptomatic. Lofgren syndrome, characterized by the coexistence of bilateral hilar adenopathy and erythema nodosum, is one of the most common acute presentations of sarcoidosis. Subacute sarcoidosis patients may experience nonspecific symptoms such as weakness, fever, weight loss, arthralgia, and peripheral lymphadenopathy [5].

Sarcoidosis granulomas, unique in their aggregation of multinucleated giant cells and epithelioid macrophages, are encircled by a rim of CD4+ T cells. B cells and CD8+ T cells are less prevalent in the vicinity of this rim. The granulomatous inflammation observed in sarcoidosis is believed to result from a dysregulated antigenic response triggered by unidentified environmental factors in genetically susceptible individuals. Onset and specific disease characteristics have been linked to genetic loci containing antigen presentation genes like HLA class II and BTNL-2. While the mechanisms remain unclear, dendritic cells are thought to play a substantial role in antigen presentation and the ongoing immune response. Recent evidence also suggests that sarcoidosis may involve not only an elevated Th1 immune response but also potential dysfunction of regulatory immune cells and immunological exhaustion, leading to the failure to eliminate antigenic substances [6]. Various treatment protocols have been proposed, with corticosteroid administration as the primary approach for symptomatic patients with abnormal function or imaging results. This is followed by a minimum of one year of steroid tapering. In cases where patients do not respond to therapy, experience severe side effects, or cannot discontinue corticosteroids, second- and third-line medications may be introduced. It's important to note that variations in clinical response and toxicity profiles highlight the need for a patient-centered approach.

A pseudoaneurysm of the SFA is characterized by the outward protrusion of one or two outer layers of the arterial wall. In contrast, a true aneurysm affects all three layers, including the intima, media, and adventitia. Clinical manifestations of a PSA may include active extravasation, pulsatile hematoma, discomfort, or ecchymosis. In chronic cases, a fibrous capsule may develop, allowing continuous communication with the arterial lumen. The clinical progression of pseudoaneurysms varies, with consequences dependent on size, the cause of injury, duration, patient comorbidities, and neck diameter. Possible side effects include expansion, rupture, embolization, extravasation with artery wall compression, and ischemia. Clinical evaluation should be highly suspicious, especially when a pulsatile mass is detected, particularly if the patient reports recent intervention [7].

Hemorrhages are contained by the surrounding tissue or by the intact middle or adventitious tunica layers. Femoral artery pseudoaneurysms have been reported frequently following vascular procedures. Since the widespread use of SFA access for endovascular operations, it has become a common complication [8]. Pseudoaneurysms can occur spontaneously or as a result of medical interventions. Both scenarios are concerning because they can lead to rupture, hemorrhage, or even sudden death. As demonstrated by our patient, the occurrence of a pseudoaneurysm without a femoral fracture following forceful trauma is a rare clinical phenomenon. The cause of pseudoaneurysms in the context of sarcoidosis remains unknown and requires further research. With advancements in endovascular repair, various treatment options have been described, ranging from conservative to surgical approaches. The "gold standard" for treatment is the surgical closure of the femoral artery pseudoaneurysm. Depending on the location of the pseudoaneurysm, the surgeon may choose to perform a simple stitch of the defect after the hematoma is removed, or a surgical repair with a patch. A hematoma is formed when there is no flow into and out of the sac, whereas blood flows in and out of a pseudoaneurysm. Indications for surgery include critical limb ischemia, rapid growth, failure of conventional treatments, skin necrosis, and compressive symptoms like neuropathy [9]. The choice of treatment is typically made by the surgeon based on the location of the pseudoaneurysm, their expertise, and the potential for minimally invasive treatment.

Conclusions

Spontaneous pseudoaneurysms of the SFA can be a rare but serious complication, potentially resulting from a range of factors, including medical interventions. Timely diagnosis and intervention are crucial for their management, with surgical closure typically considered the gold standard, especially in cases involving critical limb ischemia or infection. This report highlights that pseudoaneurysms can occur spontaneously without any history of trauma or surgery, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. These medical conditions underscore the need for ongoing research to better understand their underlying causes and to develop more tailored treatment approaches. The complexities of both sarcoidosis and pseudoaneurysms of the SFA emphasize the importance of a patient-centered and multidisciplinary approach to care, were individual factors and clinical presentations guide treatment decisions.

Competing interests and Patient consent

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- Belperio JA, Shaikh A, et al. (2022). Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis: a review. JAMA, 327:856-867.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sokhal BS, Ma A, et al. (2005). Femoral artery aneurysms. Br J Hosp Med, 83:1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jain R, Yadav A, et al. (2020). Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med, 9:1081.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA. (2007). Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med, 357:2153-2165.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gerke AK. (2020). Treatment of sarcoidosis: a multidisciplinary approach. Front Immunol, 11:545413.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Drent M, Cremers JP, et al. (2014). Pulmonology meets rheumatology in sarcoidosis: a review on the therapeutic approach. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 26:276-284.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Darigny S, Astarci P, et al. (2021). A rare case of spontaneous superficial femoral artery pseudoaneurysm in a young patient: case report and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep, 8:327.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gupta PN, Basheer A, et al. (2013). Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm as a complication of angioplasty. Heart Asia, 5:144-147.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Azzo C, Driver L, et al. (2023). Ultrasound assessment of postprocedural arterial pseudoaneurysms: techniques, clinical implications, and emergency department integration. Cureus, 15:43527.

Publisher | Google Scholor