Research Article

Utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Factors among HIV-Positive Women attending Public Hospitals in North Shoa, Ethiopia, Mixed Study

- Bacha Merga Chuko 1*

1Department of maternity and neonatology, Ameya Primary Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

2Department of maternity and neonatology, Holeta Primary Hospital, Holeta, Ethiopia.

3Department of midwifery, College of health sciences, Metu University, Metu, Ethiopia.

4Department of midwifery, College of health sciences, Salale University, Fitche, Ethiopia.

5Departments of Anesthesia, Waliso General Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

6Department of maternity and neonatology, Muka-Turi Primary Hospital, Muka-Turi, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Bacha Merga Chuko, Department of maternity and neonatology, Ameya Primary Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

Citation: M.C. Bacha, Y.G. Mitiku, N.M. Shambal, F.Mulugeta, A.K. Fikiru et al. (2024). Utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening and associated factors among HIV-positive Women attending Public Hospitals in North Shoa, Ethiopia, mixed study. Journal of BioMed Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 5(1):1-12. DOI: 10.59657/2837-4681.brs.24.093

Copyright: © 2024 Bacha Merga Chuko, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: June 14, 2024 | Accepted: June 28, 2024 | Published: July 06, 2024

Abstract

Introduction: Cervical cancer screening is used to find changes in the cells of the cervix that could lead to cancer. Despite, screening is one of the secondary preventive strategies, the case is still growing. Therefore, the study aimed to assess the utilization of cervical cancer screening services and associated factorsamong Women living with human immunodeficiency virus at public hospitals in North Shoa, Ethiopia, 2022.

Methods and materials: A mixed-study method among 396 women was conducted from April 1- June 25, 2022. Systematic random sampling was used to select women for face–to–face interviews and purposive sampling was used to select 18 mothers for in-depth interviews. The bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were done. The data were collected through the face-to- face interview by a structured questionnaire. For analysis, the data were entered into Epi data version 4.6 and exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26 software. Bivariate analysis for candidate variables selection (p< 0.25) was used. Multivariable analysis for p- value < 0.05 and 95% confidence level were considered as significantly associated.

Results: The proportion of cervical cancer screening utilization among HIV-positive women was 12.1%, 95% confidence interval of 9%- 15%. Variables like an age between 40-49 years [AOR=3.65; 95%CI=1.20, 11.07], having college above educational level [AOR = 3.04; 95% CI: 1.05, 8.80], Urban residents [AOR = 3.49; 95%CI=1.64, 7.44], and having good knowledge [AOR 3.9; 95%CI: 1.70, 8.83] were significantly associated with utilization of cervical cancer screening service. Service interruption, poor awareness, and rumor were barrier of utilization of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women. The results were presented by tables, text, and charts.

Conclusion and recommendation: The finding of this study showed that only one in ten HIV- positive women was screened. We recommend that increasing women’s knowledge about cervical cancer screening, particularly targeting the younger ones, is crucial to enhance the utilization of screening and promote health education among rural women so that recommended cervical cancer screening can be utilized more effectively.

Keywords: utilization; cervical cancer; hiv-positive women; north shoa; ethiopia

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by autonomous and uncontrolled growth of cells originating from the uterine cervix, an anatomical structure connecting the lower uterus to the vagina [1]. It begins with aberrant cell alterations known as pre-cancerous (dysplasia), which can either regress or progress into cancer over time and differs from other cancers because it grows slowly [2]. The problem is worse for women living with HIV who are at a six-fold greater risk of developing cervix cancer than non-HIV-positive women. This elevated risk manifests itself during a person's lifetime, beginning with a greater risk of acquiring the human papillomavirus, especially HPV 16 and 18 types which handle 70% of cervical carcinomas [3,4]. Cervical cancer screening is a secondary prevention type used to find changes in the cells of the cervix that could lead to cancer (4). Its efforts aim to reduce cervical cancer incidence and mortality by identifying and treating precancerous lesions in women (1). The most frequent method for cervical cancer screening is cytology, and there are alternative methods, such as HPV DNA tests and visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA). In resource-limited countries, VIA is the preferred approach [5]. About 7,445 new cervical cancer cases are reported annually in Ethiopia, with 5,338 cervical- cancer deaths [3,6-8]. Despite gains in life expectancy associated with access to HIV care and treatment in the countries the hardest hit by the epidemic, cervical-cancer in HIV-positive women has not gotten the attention or resources it deserves for prevention and treatment, and screening coverage is often low [9]. To reach vulnerable women at high risk of cervical-cancer and HIV infection, integrated human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, screening, and treatment services for both diseases must be prioritized to optimize efficiency and maximum effect [6] In 2020, an estimated 604 000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer and about 342 000 women died from the disease. It is a tragedy that every two minutes, a woman dies from cervical cancer around the world, which is alarming [5]. Of the 604 000 new cases of cervical cancer in 2020, 5% were attributable to HIV infection. Its burdens vary greatly between countries, approximately 85% of women living with HIV occur in the WHO Africa Region, 7% in South-East Asia and 4% in the Americas [9-11]. In Ethiopia, it is the second most frequent and primary cause of cancer-related death in 2015 with an estimated 4648 new cases and 3,235 dying from it [7]. Regarding medical, nonmedical, and human terms, the worldwide cost of cancer as the primary cause of long-term mortality reflects a colossal waste of resources. E.g., inside the United States, the estimated cost management has risen from $124 billion in 2010 to $157 billion in 2020 [12]. Cervical cancer and HIV are intrinsically interlinked. Women living with HIV have higher rates of HPV infection and precancerous lesions, with a six-times higher risk of invasive cervical cancer compared to women without HIV [3]. The higher risk is manifested throughout the life cycle, starting with an increased risk of acquiring HPV infection, more rapid progression to cancer, and developing cervical cancer at a younger age [13]. As women living with HIV have a higher risk of cervical cancer, they require regular screening to ensure timely detection and successful treatment of precancerous lesions to prevent them from developing invasive cervical cancer [9]. Currently, coverage for cervical cancer screening is inadequate in LMICs (10). In Ethiopia, the planned goal was to achieve 80 percent coverage for cervical cancer screening in 2016-2020 (14). Despite this, less than 10% of women had been screened in the last 5 years in 2021 [15]. Even previously many researchers tried to rule out factors like socio-demographic characteristics area of residence the flow of information and knowledge about the disease were contributed to low rates of screening uptake in the populations [16,17,18,19]. Despite these efforts has done still utilization of cervical cancer was low. To date, insufficient attention has been given to the links between cervical cancer and HIV-positive women [9] This prompted an investigation into why so few women follow recommended practices for cervical cancer screening by using mixed study approach. Consequently, the aim of this study was to assess cervical cancer screening service utilization and associated factors among HIV-positive women of North shore, Oromia. Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Area and Period

The study was carried out at public hospitals in the North Showa zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. North Shoa is bordered on the south by Sulilat Oromia special zone on the southwest by West Shoa, on the north by the Amhara Region, and on the southeast by East Shoa. It has 13 districts and one administrative town. Fiche is one of its’ towns in central Ethiopia. It is the administrative center of the North Shoa Zone of the Oromia Region and a separate woreda. The total population in the zone was 1,431,305 of whom 717,552 are men and 713,753 were women. 146,758 lived in urban and 1,284,547 were rural. There are five public hospitals, but only four of them have ART-clinic. The study was conducted from April 1-June 25, 2022.

Study Design

A facility-based, cross-sectional study design was supplemented by a qualitative study / convergent parallel study design.

Sources of population

All HIV-positive women attending ART-clinic at public hospitals in North Shoa, Ethiopia. Study population is all sampled HIV-positive women presented during data collection and who full fill inclusion criteria at public hospitals with ART-clinic in North Shoa.

Eligible Criteria

Inclusion criteria

All HIV-positive women who had a current follow-up at the ART clinic presented during data collection. Women who were unable to communicate due to any illness were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination

A single population proportion was used to estimate the sample size and the following assumptions were made.

n =

Where n = sample size; Z = standard normal distribution curve value for the 95% confidence interval (1.96) d = the margin of error or accepted error (0.03); P is the estimated utilization of cancer cervix screening among HIV-positive women was 8.7% from a study that was done at Ambo town, Ethiopia (20).

Substitution of the figures above into the formula gives a sample size of = n = = 339

= 339

By adding a 10% non-response rate the final sample size was 339+34=373

For the second objective, the sample size is calculated by using Epi-info version 7.25 and different variables with a strong correlation with the dependent variable from various types of literature were used to establish the sample size for specific objectives by using double population proportion, 80% power, 95% CI using identified associated factors with utilization of cervical cancer screening such as education Status Information from health profession and area of residence [20,21,22]. Since the sample size for specific objective one (373) is smaller than the sample size for specific objective two, Hence the specific 2 objective sample size (396) was used.

For the qualitative study

Sample size was determined after ideas of women were got saturated and 18 women were included in the study

Sampling technique and procedure

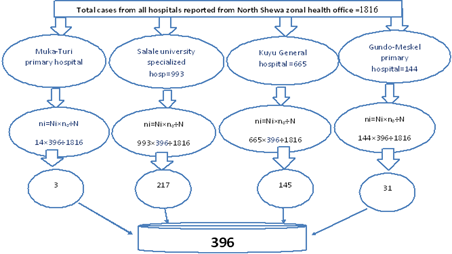

A systematic random sampling method was used to select 396 women. First, all four public hospitals with ATR-clinic found in the North Shewa zone: Muka-Turi primary hospital, salable university specialized hospital, Kayu general hospital, and Gundo Meskel primary hospital were included in the study. To select study participants from each hospital the total sample size was allocated proportionally to size as the following. Based on proportionate the total sample size of 396 was allocated to each selected hospital by the following formula.: in = Ni x no/N Where: in = number of women that are needed from each health institution Ni = total number of women who were attending within each Hospital from reports of North Shewa zonal health office (Muka-Turi primary hospital=14, Salale university specialized hospital=993, Kayu general hospital=665, Gundo Mekelle primary hospital=144). No = calculated sample size =396 N = Six months report of total HIV-positive women in North Shewa zone hospitals were received from North Shewa zonal health office =1816. Finally, for each facility, systematic random sampling was conducted at every constant interval (Kth=N/n). K=1816÷396=4.6 ~4. We selected the first participant via lottery (see figure 1).

Figure 1: schematic presentation of sampling procedure.

For qualitative part of the study

purposive sampling technique was used based on women`s willingness to participate in IDI (In-depth interview).

Study variables Dependent variable

Utilization of cervical cancer screening service

Independent variables

Age, marital status, residence, occupation, educational status, knowledge status,

Operational definitions

Cervical cancer screening utilization

Participants who had screened at least once in in the past five years were considered to have used cervical cancer screening". It was assessed by asking “Have you ever had cervical cancer screening in the past five years?”, if the respondents answered, “yes” it is considered as use cervical screening and labeled as “1” for analysis, while if the respondents answered “no”, it is taken as didn’t use cervical screening service and labeled as “0(20).

Knowledge

Seven items composite score of knowledge to measure the knowledge level of respondents regarding vulnerable groups, risk factors, signs, symptoms, and prevention methods of cervical cancer. We estimated the cumulative mean score of knowledge of participants about cervical cancer using a mean score. Based on this, those who had a score less than the mean were considered to have poor knowledge and those who had a score greater than or equal to the mean value were considered to have good knowledge [23]. Method of data collection (instruments and procedure). The principal investigator adapted the structured questionnaire in the English-language version after reviewing different literature. Then, it is translated into Afan Oromo by a language expert. A pretested structured questionnaire on 5% of the total sample size was used to collect data by four BSc nurses with face-to-face interviews and one supervisor who do not work in the service ward. The data collectors were oriented for one day by the principal investigator about the purpose of the study, how to interview and fill out the questionnaire properly. Orientation was given by the local language on how to ask and fill the questions, selection criteria of participants, keeping privacy and how to approach the respondents. We collected data during hospital visits. The data collector was informed of the selected participants, as she was selected to take part in the study. From the selected participant, informed consent was got, and the data were collected. One data collector was assigned to one hospital and supervised by the supervisor.

For the qualitative part of the study

The qualitative data was collected by using a semi- structured interview guide with probing questions linked to Utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening. During the in-depth interview, voice recorded and notes were taken. The questionnaires contain 4 guiding questions and 7 probing questions

Data quality control

Data were controlled through the orienting of data collectors and supervisors on objectives and questionnaires. Data collectors were supervised by the supervisor and the principal investigator received a report daily. Before the actual data collection pretest was performed by taking 5% of the study of the population at a fitches 01 health center. After analysis of the pre-test result, minor modification like typing error was corrected.

Also, Cronbach's alpha was computed by SPSS version 26 to assess the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaires. A construct is reliable if the alpha value is greater than 0.7 (24). The result revealed that the knowledge level was assessed consisting of seven items and the value for Cronbach’s Alpha for the knowledge level was α =0.91.

During data collection, all data were checked for completeness and consistency. After being collected, the data was cleaned manually, coded, and entered into Epi data version 4.6. Double data entry was done by one data clerk and the consistency of the entered data were cross-checked by comparing the two separately entered data then exported to SPSS version 26 software for further analysis. To ensure the consistency of the questionnaire, the English version was translated into Afan Oromo.

For the qualitative study part

To ensure the quality of data trustworthiness was considered. The fundamental criterion of trustworthiness for qualitative study as follow: To maintain the credibility, of the research findings IDI guide were evaluated by the professionals, before the data collection. Orientation about the purpose of IDI and responsibility was given before the IDI takes place to avoid unnecessary interruption and keep the rights of the participants. To maintain the transferability of the finding, appropriate probes were used to obtain detailed information on responses.

To maintain the dependability of the finding the research process member checking was made by returning the preliminary findings to the participants to correct errors and challenge what were perceived as wrong interpretations. Detailed field notes and digital audio recordings were done for all IDI and data analysis in each IDI was crossed checked and the results were reviewed in relation to themes and subthemes with their original data.

Data processing and Analysis

Collected data were cleaned and coded for completeness and accuracy, and then entered Epi data version 4.6 and exported to SPSS version 26 software was used for further analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the result in proportion, frequencies, cross-tabulation, and measures of central tendency. Tables, text, and charts were used to present the result.

A binary logistic regression was used to show factors associated with cervical cancer screening service utilization. Bivariate analysis for candidate variables selection (p< 0> 0.05.

Consequently, these results revealed Hosmer and Reshows test statistic indicates that the model adequately good fit since chi-square=6.07, do=8. P-value=.69. Hence there is no difference between the observed and predicted models.

Qualitative data were analyzed thematically by transcribing recorded audio and notes taken during the Interviews. The recorded audio was first transcribed word by word into Afan Oromo, and then translated into English by the language translator. The transcribed data into English was coded manually (color-coded) with similar ideas with the same code. Then, the narrated qualitative information was organized and categorized according to their similar ideas to form sub-themes. Sub-themes emerged together to form the main themes. Then, the study participant's comment was written in quotes. Ideas related to the objective of the study and commonly indicated by women were taken to triangulate the quantitative results.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval and clearance were taken from the Ethical Review Board of Salale Ambo University, College of Health science by Ref. number HSC/878/2022 on the date of 20/03/2022. Informed verbal consent was obtained from study participants to confirm their willingness to participate in the study after explaining the objectives, benefits, and risks of the study. Participation in the study was voluntary and a study participant has the right to accept or refuse participation in the study at any time. Confidentiality was assured and no personal details were recorded in any documentation related to this study.

Results

A total of 391 women living with HIV took part in this study and completed the questionnaire with a 98.7% response rate.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The mean age of the study participants was 41 years, SD±7 and more than one-third of women n=131(34%) fell in the 30-39 years age rang. More than half of the study participants 215 (55%) were married. One hundred thirty-four (34%) of women had attended primary education level (see table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents among HIV-positive women in North Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022

| Variables | Categories | Frequencies(n=391) | Percent |

| Age in years | ≤29 | 68 | 17 |

| 30-39 | 131 | 34 | |

| 40-49 | 94 | 24 | |

| ≥50 | 98 | 25 | |

| Marital status | Married | 215 | 55 |

| Divorce | 70 | 18 | |

| Widowed | 66 | 17 | |

| Single | 40 | 10 | |

| The educational level status of women | No formaleducation | 107 | 27 |

| Primary | 134 | 34 | |

| Secondary | 105 | 27 | |

| collage and above | 45 | 12 | |

| Women’s occupation | Housewife | 122 | 31 |

| Merchant | 58 | 15 | |

| government employee | 42 | 11 | |

| private employee | 89 | 23 | |

| Student | 29 | 7 | |

| Farmer | 52 | 13 | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 182 | 46.5 |

| Rural | 209 | 53.5 |

Knowledge about cervical cancer

Seven questions were used to assess the knowledge status of HIV- positive women in the North Shewa zone of public hospitals. Among 391 of HIV- positive women 146(37) were heard about cervical cancer screening services. Three hundred two of HIV- positive women (82%) were doesn`t know HIV-AIDS was risk factors for cervical cancer (table 2).

Table 2: Knowledge items about cervical cancer screening among participants, North Shewa, Ethiopia, 2022

| Variables | Response | Frequency | Percentage |

| Have you ever heard about cervical cancer? | Yes | 146 | 37 |

| No | 245 | 63 | |

| Do you know HIV- AIDS is the risk factors for cervical cancer? | Yes | 71 | 18 |

| No | 320 | 82 | |

| Do you know the way of transmission? | Yes | 51 | 13 |

| No | 340 | 87 | |

| Do you know the signs and symptoms? | Yes | 52 | 13 |

| No | 339 | 87 | |

| Do you know the way of prevention? | Yes | 51 | 13 |

| No | 339 | 87 | |

| Is it important for every woman who has HIV to screen for cancer of the cervix? | Yes | 232 | 59 |

| No | 159 | 41 | |

| Do you know the availability of the service? | Yes | 104 | 26.5 |

| No | 287 | 73.5 |

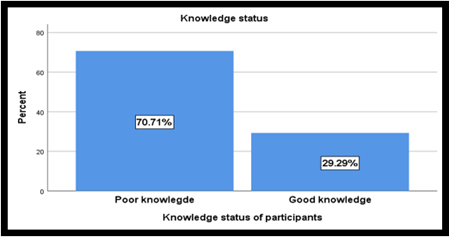

The finding of this study revealed that less than one-third (29.3%) of the respondents had good knowledge with [95%CI 25%, 34%] (figure 2).

Figure 2: Knowledge about cervical cancer among HIV-positive in North Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022 Reason for Cervical Cancer Screening services

The main reasons for screened were seeing the need 34 (71%) and obedience to the health profession was 32 (67%). Among 47 women who screened cervical cancer 4(8%) were knew the screening service was free (see table 3).

Table 3: Reason for screening among HIV-positive women in North Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022

| Response n=47 | Frequency | Percentage |

| Saw the need for screening | 34 | 71 |

| Obedience to health professional’s instructions | 32 | 67 |

| I am at risk of getting cervical cancer | 17 | 35 |

| The service was available at the clinic | 6 | 13 |

| The screening service was free | 4 | 8 |

| I know someone who screened | 4 | 8 |

| My husband encouraged me | 4 | 8 |

Barrier of Cervical Cancer Screening

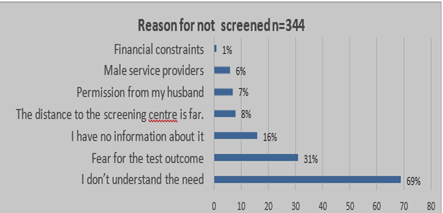

The current study was showed that in contrast to motivators, there are barriers to screening services. The most common barriers mentioned were didn’t understand the needs 68.43% and fear of test outcome while financial constraints 1% were the least stated (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Barriers of cervical cancer screening services among HIV-positive women in North Shoa, Ethiopia, 2022 Prevalence of Utilization of Cervical cancer screening

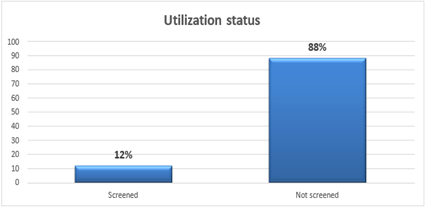

In this study, we have found that 12% [95% CI 9%, 15%] of HIV-positive women were utilized cervical cancer screening at least once in their lifetime (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Utilization of cervical cancer screening services among HIV-positive women in North Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022

Associated factors for Utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening

In bivariate logistic regression analysis, the age of women, marital status, maternal occupation, area of residence, educational level of women, information about screening services and knowledge level of women were candidate variables for multivariate analysis at (p-value less than 0.25). After controlling a possible confounding variable by multivariable logistic regression analysis, age, educational level, residence, and knowledge status had a significant association with the utilization of cervical cancer screening. Adjusted in a table 4. Women aged 40-49 years were 3.65 [AOR = 3.65, 95% CI=1.20, 11.07] times more likely to receive cervical screening services when compared to women aged ≤29 years old. This study found that women who lived in urban areas were 3.49 times [AOR = 3.49, 95%CI=1.64, 7.44] more likely to receive cervical cancer screening service utilization as compared to those who lived in rural areas. The odds of cervical cancer screening service utilization among those having educational level college and above were 3.04 times [AOR = 3.04, 95% CI:1.05, 8.80] higher as compared to those who had informal education. Also, women who had good knowledge about cervical cancer were 4 times [AOR 3.9=, 95%CI: 1.70, 8.83] more likely to be screened as compared to those who had poor knowledge about cervical cancer.

Table 4:Bivariate and multi-variable analysis of selected variables with cervical cancer screening utilization among HIV-positive women in North Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022

| Variables | Screening service utilization | COR [95%CI] | P<.25 | AOR [95%CI] | P<.05 | ||

| Yes | No | ||||||

| Age category | ≤29 | 6 | 62 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30-39 | 15 | 116 | 1.33[.49,3.61] | .56 | 1.757[.57,5.33] | .320 | |

| 40-49 | 20 | 74 | 2.79[1.05,7.38] | .03 | 3.65[1.20,11.07] | .022** | |

| ≥50 | 6 | 92 | .67[.20,2.18] | .51 | .94[.26,3.42] | .936 | |

| Area of residence | Rural | 13 | 196 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Urban | 34 | 148 | 3.46[1.76,6.79] | .000 | 3.49[1.64,7.44] | .001** | |

| The education a l level of woman | No formal education | 9 | 98 | 1 | |||

| Primary | 13 | 121 | 1.17 [.48,2.85] | .73 | 1.05 [.39,2.82] | .909 | |

| Secondary | 10 | 95 | 1.14 [.44,2.94] | .77 | .60 [.21,1.75] | .359 | |

| collage and above | 15 | 30 | 5.4[2.16,13.69] | .00 | 3.04 [1.05,8.80] | .040** | |

| Knowledge status | Poor | 15 | 262 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Good | 32 | 82 | 6.81 [3.51,13.2] | .000 | 3.9 [1.70,8.83] | .001** | |

Keys: ** =Statistically significant at p less than 0.05; 1=Reference; COR=Crude Odds Ratio; Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Qualitative study results

A total of 18 HIV-positive women who attending Public Hospitals in North Shewa (Muka-Turi primary hospital, Salale university specialized hospital, Kuyu general hospital, Gundo Meskele primary hospital) were participated in in-depth interviews. The results of the qualitative study showed that among 18 women, the age of women was ranged from 24-67 years old. Half of the women 9 (50%) who participated in IDI were living in urban areas.

The finding of the qualitative study revealed that the barrier of utilization of cervical cancer screening was identified by using interview guide questions with probing. Six sub-themes were formed based on similarities of women`s opinions. Then, the sub-theme was merged together, and three main themes were formed.

Themes 1: Services interruption

Women who were faced services interruption were less likely to utilize cervical cancer screening. This was supported by the result from IDI: “I came here from the Countryside for follow-up of HIV AIDs. I have started follow-up at this hospital. When I finished my medication, I came back to this hospital. Then, doctor working there told me about the benefits of cervical cancer screening and he told me to have cervical cancer screening. Then he passed my folder to the cervical cancer screening room. He told me to go there and get the service. I went to the cervical cancer screening room. Health care providers working there told me to keep a little until he brings material from the store. But, after some minutes he returned from the store and told me that the item was not there and he told me an appointment. Today I come for my second appointment” (Women participated in IDI 15).

Other women narrated; “I referred from fiche health center for cervical screening. At that day the service was not given. Health care provider who is working there informed to return at the day which services given and he appointed me. At my appointment day Health care provider who gives services was not there, now I come for the three times to get cervical cancer screening services. I recommend that it well if a service was given at all days” (Women participated in IDI 04).

Women explained as: “I was referred for a cervical screening from Fiche Health Center. However, service was not provided at that day. The on-site healthcare practitioner gave me an appointment and told me to return on the day the services were provided. I came three times to receive cervical screening services since the healthcare provider who was supposed to administer the services was not there on the day of my appointment. I think it would be great if services were provided every day” (Women participated in IDI 10).

Women responded as: “I came for cervical cancer screening services as well as for follow-up. But I didn’t get service at this day. Doctors who are working at this room told me that there is no medical supply to give this service for you” (Women participated in IDI 17).

Women narrated as: “I visit for follow-up as well as cervical cancer screening services. However, on this particular day, I was not served. The medical staff in this room informed me that there isn't enough medical equipment to provide you this service” (Women participated in IDI 15).

Themes 2: Poor Awareness

The finding of the present qualitative study showed that the respondents who were not awared on cervical Cancer Screening were no utilizing Cancer Screening services. The following were some of the women`s ideas: “I was transferred from other health center to this hospital. Then I started my follow up at this hospital two months ago. The health care giver at this hospital doesn`t inform me the benefits of cervical cancer screening he said for me simply you have to get cervical cancer screening. At that time, I didn`t understand the advantage of cervical screening properly” (Women participated in IDI 05).

Women explained as: “I didn`t understands the advantage of cervical screening after infected with HIV AIDS. No one advices given for me on advantage of cervical cancer screening” (Women participated in IDI 11).

Themes 3: Rumor

The rumor was also one of the barriers of utilizing cervical cancer screening services. This was explained by: “I was grown up in rural area. After testing my blood when I went for my check-up, they informed me that I had HIV/AIDS and moved me to the ART department. At this hospital, I received ART services for a full year. Upon learning about cervical cancer screening services, I spoke with some friends, who informed me that cervical cancer doesn't affect people who are too elderly. They told me that you didn't need this particular service. Then, I instantly left the service” (Women participated in IDI 13).

Women who participate in IDI explained: “As I heard from community lived with them. Person who was once contracted HIV AIDS disease no need of cervical cancer screening” (Women participated in IDI 05).

Other respondents narrated: “Before I came here, I had follow-up at health center. Now I was transferred to this hospital for ART services. Usually, I heard that cervical Cancer screening was not important for women who didn`t have sexual intercourse with more men. After that I ignore using of cervical Cancer screening service” (Women participated in IDI 16).

Discussion

This study aimed to summarize the utilization of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among HIV-positive women at a public hospital in North Shewa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022. This study found that only 12% with [95% CI 9.1%- 15%] of women had utilized cervical cancer screening. In line with this finding; Study was done in Taiwan 14.7 percentage Addis Ababa, 11.5% and Northwest Ethiopia 10% [22,25,26]. However, this finding was lower than the study conducted in Northern Italy 91% Ontario, Canada 68% in Côte d’Ivoire 72.5%, Estonia 61.45% [28,30]. The probable explanation for the discrepancy might be because the difference in utilization of cervical cancer screening is attributed to the difference in socio-demographic status, geographical barriers, availability, and accessibility of services. Another probable explanation might be the ineffectiveness of a health information system (HIS) on a routine collection of essential data and generation of regular monitoring reports at the health-facility level. This study found that women aged 40-49 years were positively associated with cervical cancer screening when compared to women aged ≤29 years old. It is concurrent with studies in Taiwan and Côte d’Ivoire [25,29]. This is explained as women’s age increases, the probability of getting information about cervical cancer and its screening will be increased, which leads them to use cervical cancer screening services and the chance to have more contact with health facilities increases as age increases.

The odds of cervical screening service utilization among those having an educational level of college and above were positively associated as compared to those who had informal education. This study finding is concurrent with studies done in Ghana Côte d’Ivoire [29,31]. This is explained by the education enhances the knowledge of screening services and access to communicable disease and reproductive health information that might help women to utilize screening to the recommended time. Education might lead to an increased focus on preventative care and a decrease in health-risk behaviors. According to this finding, there is a sizable difference between rural and urban women's rates of cervical cancer screening utilization. Women who lived in urban areas were positively associated to receive cervical cancer screening services utilization as compared to those who lived in rural areas. This is supported by a study done in the United States of America in Ethiopia [17,32]. This is explained by women of urban dwellers were more accessible to information and might have more knowledge about the need to be screened. Finally, knowledge about cervical cancer screening was another significant factor in the utilization of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women. This study found that women who had good knowledge about cervical cancer were positively associated with cervical cancer screening as compared to those who had poor knowledge about cervical cancer. This also supported by qualitative study findings. Women who had less awareness on cervical cancer screening were less likely to utilize cancer screening. This is supported by research done in Northern Tanzania Ethiopia.

Hawassa town, Ethiopiaand Addis Ababa city [19,20,23,33)]. The possible explanation might be being aware of disease-associated risk behaviors may promote prevention strategies, sustain healthy lifestyles and positive choices for seeking screening services.

Limitation

Since the data were collected from patients only attending hospitals where a cervical cancer screening program is available, the findings of this study might not be generalized to all age-eligible women for cervical cancer screening receiving in public health institutions in the North Shoa, zone. Finally, during the interview, very few women had trouble remembering how they had previously been exposed to risk factors.

Conclusion

The finding of this study showed that nearly one in ten HIV-positive women was screened. The main factors that were significantly associated with cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women were: age, being an urban resident, having screening service information, and having good knowledge about cervical cancer. The results of this study could potentially be applied by stakeholders to enhance cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive and prevention programs. So, some recommendations had been made. All age eligible women having ART follow-up should utilize for cervical cancer screening services, creating awareness on benefit of cervical cancer screening and engaging cervical cancer survivors (persons who have successfully been treated for cervical cancer) in education and advocacy for cervical cancer prevention. Work hard to empower rural women with health education which enhances the utilization of recommended cervical cancer screening.

What already known on this topic. Magnitude of utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening. This study adds. Magnitude of Cervical Cancer Screening among HIV-positive women. Identify factors associated with Cervical Cancer Screening among HIV-positive women. Identify barrier Cervical Cancer Screening utilization among HIV-positive women.

Declarations

Funding

There is no fund

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict-of-interest respect to this study.

Data availability

The corresponding author is willing to provide the dataset that was used in this study based upon reasonable request using’ bachamerga11@gmail.com

Author contribution

All the authors contributed to the proposal development, questionnaires, and data collecting process, analysis, and interpretation.

Data curation by: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Mitiku Yonas Gindaba Mulugeta Feyisa, and Shambel Negese Marami

Format analysis: Bacha Merga Chuko, Mitiku Yonas Gindaba, Mulugeta Feyisa, Gebreyes Mengistu Geda and Shambel Negese Marami

Investigation: Bacha Merga Chuko, Mitiku Yonas Gindaba, Mulugeta Feyisa, and Shambel Negese Marami

Methodology: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Mitiku Yonas Gindaba, Mulugeta Feyisa, and Shambel Negese Marami

Revise the manuscript: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Mitiku Yonas Gindaba Mulugeta Feyisa, Gebreyes Mengistu Geda and Shambel Negese Marami

Final version of the article was checked by all authors.

Consent

Informed consent was taken from every study participant before the actual data collection started.

Abbreviations

ART; Anti-Retroviral Therapy, H

PV; Human-Papilloma Virus,

IARC; International Agency for Research on Cancer,

STI; Sexually Transmitted Infection,

WLHIV; Women Living with Human Immune Virus

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Salale University, college of health science, Department of Midwifery and data collectors for their contribution to accomplishing this research

References

- WHO. (2020). WHO framework for strengthening and scaling- up of services for the management of invasive cervical cancer.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Christina RC. (2018). What Every Woman Should Know about Cervical Cancer.

Publisher | Google Scholor - WHO. (2020). New WHO recommendations on screening and treatment to prevent cervical cancer among women living with HIV Policy brief, 1-6.

Publisher | Google Scholor - ACOG. (2021). Cervical Cancer Screening, 20024.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Health Organization. (2021). Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem and its associated goals and targets for the period, United Nations General Assembly, 1-3.

Publisher | Google Scholor - WHO. (2020). Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem.

Publisher | Google Scholor - FMOH. (2015). National cervical cancer prevention training package participant manual.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ethiopia ICO/IARC on HPV report. (2021). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report.

Publisher | Google Scholor - UNAIDS. (2017). Data Program HIV/AIDS [Internet], 1–248.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Stelzle D, Tanaka LF, Lee KK, Ibrahim Khalil A, Baussano I, Shah ASV, et al. (2021). Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Heal, 9(2):e161–e169.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Menon S, Rossi R, Zdraveska N, Kariisa M, Acharya SD, Vanden Broeck D, et al. (2017). Associations between highly active antiretroviral therapy and the presence of HPV, premalignant and malignant cervical lesions in sub-Saharan Africa, a systematic review: Current evidence and directions for future research. BMJ Open, 7(8).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bona LG, Geleta D, Dulla D, Deribe B, Ayalew M, Ababi G, et al. (2021). Economic Burden of Cancer-on-Cancer Patients Treated at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. Cancer Control, 28:1-288.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chambuso RS, Kaambo E, Stephan S. (2017). Observed Age Difference and Clinical Characteristics of Invasive Cervical Cancer Patients in Tanzania; A Comparison between HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Women. J Neoplasm. 02(03).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cancer N, Plan C. (2020). Federal Ministry of Health.

Publisher | Google Scholor - WHO. (2021). Cervical cancer profile.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Woldetsadik et al. (2020). Socio-demographic characteristics and associated factors influencing cervical cancer screening among women attending in St. Paul’ s Teaching and Referral Hospital, 1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Locklar LRB, Do DP. (2021). Rural-urban differences in HPV testing for cervical cancer screening. J Rural Heal Off J Am Rural Heal Assoc Natl Rural Heal Care Assoc.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mugassa AM, Frumence G. (2020). Factors influencing the uptake of cervical cancer screening services in Tanzania: A health system perspective from national and district levels. Nurs Open, 7(1):345-354.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mrema D, Ngocho J. (2021). Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening and the Associated Factors Among Women Living. With HIV in Northern Tanzania.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Assefa et al. (2019). Cervical cancer screening service utilization and associated factors among HIV positive women attending adult ART clinic in public health facilities, Hawassa town, Ethiopia a cross-sectional study, 5:1-11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Getachew S, Getachew E, Gizaw M, Ayele W, Addissie A, Kantelhardt EJ. (2019). Cervical cancer screening knowledge and barriers among women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One.14(5):1-13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nega et al. (2018). Low uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV positive women in Gondar University referral hospital. Northwest Ethiopia: cross-sectional study design, 1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shiferaw S, Addissie A, Gizaw M, Hirpa S, Ayele W. (2018). Cancer Medicine. 1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tavakol M, Dennick R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ.2:53-55.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chen YC, Liu HY, Li CY, Lee NY, Ko WC, Chou CY, et al. (2018). Low papanicolaou smear screening rate of women with hiv infection: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan, 2000-2010. J Women’s Heal. 2018;22(12):1016-1022.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Belete et al. (2015). Willingness and acceptability of cervical cancer screening among women living with HIV / AIDS in Addis Ababa , Ethiopia : a cross sectional study. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract, 4-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Maso LD, Franceschi S, Lise M, Bianchi PS De, Polesel J, Ghinelli F. (2018). Self-reported history of Pap-smear in HIV-positive women in Northern Italy: a cross-sectional study.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Burchell AN, Kendall CE, Cheng SY, Cotterchio M, Bayoumi AM, Richard H, et al. (2017). PT US CR. Prev Med (Baltim).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tchounga B, Boni SP, Koffi JJ, Horo AG, Tanon A, Messou E, et al. (2019). Cervical cancer screening uptake and correlates among HIV-infected women: a cross-sectional survey in Côte d ’ Ivoire , West Africa, 3-5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fitzpatrick M, Pathipati MP, McCarty K, Rosenthal A, Katzenstein D, Chirenje ZM, et al. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of cervical Cancer screening among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women participating in human papillomavirus screening in rural Zimbabwe. BMC Womens Health, 20(1):1-10

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ebu NI. (2018). Socio-demographic characteristics influencing cervical cancer screening intention of HIV-positive women in the central region of Ghana. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract, 5(1):3-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Oncol A, Treat R, Gelibo T, Roets L, Getachew T, Bekele A. (2017). Advances in Oncology Research and Treatments Coverage and Factors Associated with Cervical Cancer Screening: Results from a Population-Based WHO Steps Study in Ethiopia. 1(2):1-5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mekonnen BD. (2020). Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake and Associated Factors among HIV- Positive Women in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 12-155.

Publisher | Google Scholor