Research Article

Tubogram, A Useful Investigation for Evaluation of Patients Post Cholecystostomy Drain for Acute Cholecystitis, Single Centre Experience

- Badreldin Mohamed *

- George Simmons

- Khalid M. Bhatti

- Sami Taha

- Abdalla Hassan

- Muhammad Chauhan

- Salma Babikir

- Mohamed Mohamed

- Diya Mirghani

- Ruben Canelo

Department of General and Vascular Surgery, Cumberland infirmary, Newtown Road, Cumbria, UK.

*Corresponding Author: Badreldin Mohamed, Department of General and Vascular Surgery, Cumberland infirmary, Newtown Road, Cumbria, UK.

Citation: B Mohamed, G Simmons, Khalid M Bhatti, S Taha, A Hassan, et al. (2023). Tubogram, A Useful Investigation for Evaluation of Patients Post Cholecystostomy Drain for Acute Cholecystitis, Single Centre Experience. International Journal of Medical Case Reports and Reviews, BRS Publishers. 2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2837-8172.brs.23.006

Copyright: © 2023 Badreldin Mohamed, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: November 17, 2022 | Accepted: December 06, 2022 | Published: January 02, 2023

Abstract

Background: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the gold standard treatment for cholecystitis. However, for co-morbid or unstable patients, a less invasive approach can be adopted such as cholecystostomy drain (CD) insertion. CD can be a bridging operation or can be used as a definitive treatment if patient unsuitable for surgery.

Methods: Retrospective study of patients who had Tubogram at Cumberland Infirmary, post CD for non-malignant cause between January 2019 and January 2022, comparing their outcome with the patients who did not undergo tubogram investigation. Patient data list collected from information department, Cumberland Infirmary.

Results: Cholecystostomy drain placed for 58 patients; 21 patient (36.21%) had tubogram. Of the 58,44 patients (75.86%) had one CD; only 10 patients (22.73%) of them had tubogram. 14 patients had more than one CD (11 patient of them had tubogram). 66.67% patients had tubogram at 3-4 weeks following CD insertion. Outcome of tubogram patients was 47.62% (n=10) had Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC) 6 weeks after cholecystostomy drain removal and 28.57% (n=6) had Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography then Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Non-tubogram patients’ group had more visits to same day emergency clinic comparing to tubogram patients’ group.

Conclusion: Tubogram is a useful, cheap, non-invasive test linked with lower recurrence rate of cholecystitis symptoms after removal of CD; it is also associated with earlier CD removal. We recommend that tubogram should be a routine investigation for all patients three to four weeks post CD insertion.

Keywords: acute cholecystitis; cholecystostomy drain; tubogram; cumberland infirmary

Introduction

Gallstones are prevalent in 10-15% of the adult population in the United Kingdom [1]. It is one of the most common emergency department attendances and admissions to a general surgical department, estimated to account for 10% of all patients presenting as an emergency with abdominal pain, with more than half of this patient cohort being elderly [1, 2]. Acute biliary infection, as define by Tokyo guidelines, can be acute cholangitis or acute cholecystitis which can be varied from oedematous cholecystitis, progressing to necrotizing cholecystitis, suppurative cholecystitis and ultimately perforation of the gallbladder or pericholecystic abscess [2].

Tokyo guidelines 2018 classifies acute cholecystitis into; (1) Grade I (mild) acute cholecystitis, can be defined as acute cholecystitis in a healthy patient with no organ dysfunction and mild inflammatory changes in the gallbladder. (2) Grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis, associated with any one of the following conditions: elevated white blood cell count more than 18000 >18,000/mm3, palpable tender mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant, duration of complaints more than 72 hours or marked local inflammation (gangrenous cholecystitis, pericholecystic abscess, hepatic abscess, biliary peritonitis, emphysematous cholecystitis. (3) Grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis associated with any one of the following: hypotension requiring treatment with dopamine 5 μg/kg per min, or any dose of norepinephrine, decreased level of consciousness, respiratory dysfunction, oliguria, serum creatinine more than 2.0 mg/dl, hepatic dysfunction: international normalized ratio (INR) more than 1.5 (INR>1.5) or platelet count less than 100,000/mm3 [2].

The gold standard treatment of acute cholecystitis in United Kingdom is laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the index admission, or within seven days of presentation [3]. On late presentation patients can be treated with antibiotics followed by interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy [4]. Patients who are not suitable for surgery either because of frailty, sever sepsis or co-morbidities, alternative options such as cholecystostomy drain can be used as a treatment option [5].

Cholecystostomy drain can be a bridging operation to allow the patients to recover from acute illness and become stable enough to undergo surgery at a later date [5]. For those who remain unsuitable or too co-morbid for surgery, cholecystostomy drain can be used as a definitive treatment [5, 6]. Following cholecystostomy drain insertion, the decision to remove the drain is carried out based on several factors: clinical, laboratorial and radiological investigations, such as computed tomography (CT) abdomen or Cholangiogram [7].

Radiologic visualization of the biliary tree was introduced by Burckhardt and Müller in 1921, however the first report of Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography (PTC) was done by Huardand Do-Xuan-Hop, et al. in 1937, they used lipiodol as the contrast agent [8]. With the rapid advancement of cross-sectional radiological imaging, especially after introduction of Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP), it is recommended that percutaneous fluoroscopic investigations of the biliary tree only done if intervention procedures are needed or planned [8].

Materials & Methods

Information was gathered retrospectively from medical records for patients of either sex who were over the age of 18 and who had cholecystostomy drain (for non-malignant cause-acute cholecystitis) over three years at Cumberland Infirmary (Carlisle- United Kingdom) between January 2019 and January 2022 and comparing their outcome post cholecystostomy drain placement with the patients who did not have tubogram investigation.

Aim of the study is to investigate and compare the clinical factors and the outcome of patients who had tubogram as part of cholecystostomy drain management of acute cholecystitis at Cumberland Infirmary versus those who did not undergo tubogram.

Inclusion criteria was all patient elder than age of 18 who had cholecystostomy drain placed for management of acute cholecystitis. All patient who had cholecystostomy drain placed for malignant biliary tract lesion, bridging bile duct stricture, bile duct fistula output diversion, biliary tract decompression in cholangitis were excluded from our study group.

58 patients had cholecystostomy drain for acute cholecystitis management, 21 patients of them had been investigated by tubogram during their management course. The patient data list from which they were identified and anonymised for inclusion was collected and collated by Cumberland Infirmary Information Department, using the code J 24.1. The need for patient consent and approval from the research council was discounted because the study was observational and did not involve identifying information about individual patients.

The median patients age, time till removal in weeks, number of cholecystostomy drain placed for each patient, Time from cholecystostomy drain placement till tubogram had been done, other radiological investigations performed after placement of cholecystostomy drain apart from tubogram, numbers of visits to same day emergency clinic, outcome of the patients who had cholecystostomy drain and/or tubogram and post-procedure complications were among the data points collected. SPSS V. 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY USA) was used for both descriptive and inferential analyses of the data.

In our institution, patients selected for cholecystostomy drain insertion based on their clinical presentation, and local trust guideline (either grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis patients, who were too ill because of sever biliary sepsis or not fit to have general anaesthesia or Grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis patients as per Tokyo Guidelines 2018), the advantages and disadvantages of the cholecystostomy drain procedure discussed with the selected patients, and written consent was obtained. Cholecystostomy drain was then performed under local anaesthesia by interventional radiologists in the radiology department. For tubogram investigation, verbal consent was obtained from the selected patients and tubogram performed in the radiology department as well.

Results

Of 58 patients had cholecystostomy drain inserted, from January 2019 to january2022. 21 (36.21%) patients had tubogram done through the cholecystostomy drain, 13 patients (61.90%) of them were male, and eight patients (38.10%) were female (Table 1).

| Patients age in years | CD patients’ number (N) | CD patients’ percentage (%) | Tubogram patients’ number (N) | Tubogram patients’ percentage (%) |

| 20-30 years | 01 | 01.72 % | 00 | 00.00 % |

| 30-40 years | 02 | 03.45 % | 00 | 00.00 % |

| 40-50 years | 02 | 03.45 % | 01 | 04.76 % |

| 50-60 years | 10 | 17.24 % | 03 | 14.29 % |

| 60-70 years | 14 | 24.14% | 05 | 33.33 % |

| 70-80 years | 14 | 24.14% | 07 | 23.81 % |

| 80-90 years | 15 | 25.68 % | 05 | 23.81 % |

Table 1: Cholecystostomy drain (CD) patients and tubograms patients’ demographics

Of the 58 patients underwent cholecystostomy drain in our study; 44 patients (75.86%) had one drain inserted, only ten patients (22.73%) of them had a tubogram; ten Patients (17.24%) had two cholecystostomy drains inserted, seven patients (70%) of them had a tubogram; three patients (05.17%) had three cholecystostomy drains and one patient (01.72%) had four drains, all of these patients had a tubogram. For the patients who had more than one drain, they were investigated with tubogram on recurrence of the symptoms (Table 2).

Five patients out of the 14 patients (35.7%) who had more than cholecystostomy drain, drain removed early in the first week, either for dislodgement or accidental misplacement, whilst the remaining cohort had recurrence of symptoms. In regard to the duration of the cholecystostomy drain, of the 15 patients (25.86%) who had the cholecystostomy drain for two weeks or less, only one patient (6.67%) of them had a tubogram. similarly, only one patient out of the nine (15.52%) patients who had drain removed in three weeks had a tubogram. The number of patients who had a tubogram increase as duration of the insertion of the cholecystostomy drain prolongs, such that out 17 patients (29.31%) who had the cholecystostomy drain for six weeks or more 12 patients (70.59%) of them underwent tubogram during the due period cholecystostomy drain management (Table 2).

| Duration of the CD/ weeks | Number of tubogram patients (N) | Percentage of tubogram patients (%) |

| Duration of the CD | ||

| 2 weeks | 01 | 04.76 % |

| 3 weeks | 01 | 04.76 % |

| 4 weeks | 05 | 23.82 % |

| 5 weeks | 02 | 09.52% |

| 6 or more weeks | 12 | 57.14% |

| Number of CD | ||

| 1 drain | 10 | 47.62% |

| 2 drains | 07 | 33.33 % |

| 3 drains | 03 | 14.29 % |

| 4 drains | 01 | 04.76 % |

Table 2: Duration/Number of Cholecystostomy drain (CD) in tubogram patients in weeks

The timing of requesting tubogram in our study group is around the third to fourth week from the cholecystostomy drain insertion, as 14 patients (67%) had tubogram around this time of the drain insertion. This is correlative as the patients by this time will be reviewed in same day emergency clinic (SDEC) to assess their clinical suitability for cholecystostomy drain removal (Table 3).

| Time from CD insertion to tubogram in weeks | Number of patients (N) | Percentage of patients (%) |

| 2 weeks | 01 | 04.76 % |

| 3 weeks | 07 | 33.33 % |

| 4 weeks | 07 | 33.33 % |

| 5 weeks | 05 | 23.82% |

| 6 weeks | 00 | 00.00% |

| 7 or more weeks | 01 | 04.76 % |

Table 3: Time from Cholecystostomy drain (CD) insertion to tubogram in weeks

Apart from tubogram, 17 patients (80.95%) had computed tomography (CT) abdomen scan at some stage from the time of cholecystostomy drain insertion till its removal, in comparison with non tubogram patients' group of which 18 patients (48.67%) had been investigated with CT abdomen. However, abdominal ultrasound scan was requested in 14 patients (66.67%) of tubogram patients' group and in only eight patients (21.62%) non tubogram patients' group. Most of these investigation modalities were requested prior requesting the tubogram.

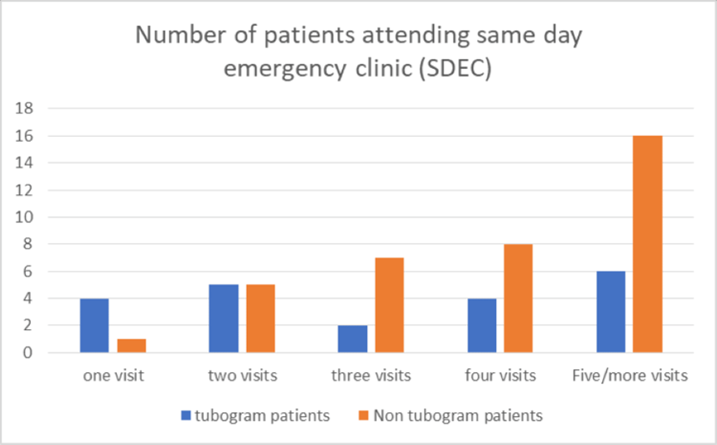

The cholecystostomy drain patients who were managed without been investigated with tubogram had more SDEC visits in comparison of tubogram patients' group. As four patients who underwent tubogram visited SDEC only once and in the non tubogram patients' group, and only one patient visited SDEC once till the time of cholecystostomy drain removal. In contrast to this, 16 patients of the non-tubogram group visited SDEC five times or more, whilst in tubogram group only six patients attended SDEC five times or more during C cholecystostomy drain management period (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of patients versus same day emergency clinic (SDEC) visits

The outcome of tubogram patients, 11 patients (52.38%) had common bile duct (CBD) stones and underwent Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP), six patients of them underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and ten patients (47.48%) tubogram was normal and showed flow of the contrast from the cholecystostomy drain to cystic duct, CBD and to proximal small intestine (via sphincter of Oddi). However, the total number of the patients who had Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in tubogram patients were 16 patients (76.19%). No deaths related directly to the cholecystostomy drain or tubogram reported in our study group, however two patients passed away as a complication of sever biliary sepsis within two days post cholecystostomy drain insertion. No complications related to cholecystostomy drain insertion or tubogram reported in our patients, including allergy to contrast medium (Table 4).

| Patients’ outcome | CD patients’ number (N) | CD patients’ percentage (%) | Tubogram patients (N) | Tubogram patients’ percentage (%) |

| Conservative Management | 26 | 44.83% | 05 | 23,81% |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) | 11 | 18.97% | 11 | 52.38% |

| Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy 6 weeks after CD removal | 19 | 32.76% | 10 | 47.62% |

| ERCP and Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy | 11 | 18.97% | 06 | 28.57% |

Table 4: Outcome of the Cholecystostomy drain (CD) patients versus tubogram patients

Discussion

Cholecystostomy drain technically has a high success rate with few short-term complications and a low mortality attributed to the procedure. No death directly related to the procedure has been reported in our study group [9]. Patients without severe sepsis responded well to cholecystostomy drain, however there is limited data about the role of the cholecystostomy drain in severe sepsis or septic shock; therefore, many authors tried to examine the efficacy of cholecystostomy drain in critically ill patients such as Simorov, et al. in the study of 1725 critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis, suggested that cholecystostomy drain decreases the morbidity, recurrence rate and significantly improves the peri-procedure outcome, comparing to the surgery. In our study group no cholecystostomy drain related mortality was reported and no significant complication encountered, besides recurrence of the biliary symptoms which was recorded in the patients who had more than one cholecystostomy drain. Out of the 14 patients (24.13%) who had a inserted, nine patients (64.29%) of them had recurrence of the symptoms that required another drain insertion [9, 10].

The decision on cholecystostomy drain removal after resolution of cholecystitis is controversial as there is no definitive guideline regarding the matter. Therefore, many authors believe that removal of the drain prior to the surgery is associated with higher recurrence rate and morbidity [11, 12]. However, many authors supported cholecystostomy drain removal for many reasons. Firstly, the tract requires three to four weeks to mature based on previous work by D’Agostino, et al. the mature tract will prevent intra-peritoneal bile leak so the drain can be safely removed. In our study group five patients (23.82 %) who had tubogram had their drain removed in four weeks, compared to seven patients (18.92%) who did not have a tubogram. Whereas 12 patients (57.14%) had cholecystostomy drain removed after six weeks or more in tubogram patients' group and five patients (13.51%) in the non-tubogram cohort [13]. Secondly, prolonged indwelling of cholecystostomy drain was found to be a precipitating factor to recurrent biliary events; in our study group, 14 patients (24.13%) had more than one cholecystostomy drain inserted and nine patients (64.29%) of them had recurrence of the symptoms that required another drain insertion, all of them had cholecystostomy drain more than five weeks [14].

Many authors were inquiring about patency of the biliary tree prior the cholecystostomy drain removal. By cholangiography or tubogram, they define biliary patency as no obstruction of cystic duct, common bile duct as well as contrast to be seen in the duodenum, however other authors believe it is only a non-obstructed cystic duct [15-17].

Tubogram can be performed as patient lying supine, with contrast injected through the cholecystostomy drain and x-ray imaging to visualize the bile ducts [7]. Hung, et al. reported in a retrospective study that no significant difference in peri-procedure complications, hospital stay or timing of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy between the patients who had tubogram or those who did not [18]. In our study group, 11 patients (52.38%) of the tubogram group had biliary obstruction and underwent Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP), no patient of non tubogram group needed ERCP.

Loftus et al. compared the outcome of the patients who had routine or on demand tubogram and concluded that the recurrence rate is similar between the two groups, however patients who underwent requested tubogram had early cholecystostomy drain removal as well as laparoscopic cholecystectomy [19]. In our study group, ten patients (47.62%) of tubogram group had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, while on the non-tubogram group nine patient (24.32%) had laparoscopic cholecystectomy. All patients had tubogram on demand rather than routine as they were symptomatic prior tubogram.

The recurrence rate of acute cholecystitis was low in the study conducted by Park, et al. as the use of the clamping test showed protective factors prior drain removal [20]. On the clamping test, patients should tolerate continuous clamping of the cholecystostomy drain for 24-48 hours and should be symptom free. However, if the patient experienced any symptoms or signs of recurrence of cholecystitis or biliary symptoms, the cholecystostomy drain should not be removed [20, 21]. Assessing the patency of the biliary system was evident in our as 70% of patients who had two drains investigated by tubogram was due to recurrence of their symptoms. All of the patients who had three drains or more had tubogram as well due to recurrence of symptoms.

The burden on the health system is high with patients who did not have a tubogram early during their management, as they had more frequent same day emergency clinic (SDEC) visits. 16 patients (43.24%) visited SDEC five times or more during their management, while in tubogram patients only six patients (28.57%) visited SDEC five times or more chart [1]. Similarly, these patients also underwent further radiological investigations, such as Computed Tomography (CT) abdomen and abdominal ultrasound scan (USS) prior tubogram. Frequents imaging side-by-side with recurrent hospital visits (SDEC) increases the cost burden on the National Health Service (NHS).

The limitations of the study were the limited number of published literatures related to the investigation topic, the relatively small study cohort and the study was retrospective study which is subjected to selection bias.

Conclusions

The management of the patients post cholecystostomy drain is diverse and individualized. While an interval of six to eight weeks between cholecystostomy drain and cholecystectomy is commonly applied, the optimal timing is still inconsistent. The decision to maintain or remove cholecystostomy drain is controversial, however, more evidence supports cholecystostomy drain removal. Visualization of the patency of the biliary tree by tubogram prior cholecystostomy drain removal is highly recommended.

Tubogram is a useful, cheap and non-invasive test linked with lower recurrence rate of biliary symptoms following removal of cholecystostomy drain and is also associated with earlier cholecystostomy drain removal.

We recommend that all patient who have cholecystostomy drain should have a tubogram as a routine investigation after four weeks post cholecystostomy drain insertion.

References

- Edlund G, Ljungdahl M: Acute cholecystitis in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1990, 159:414-6. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81285-1

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fumihiko Miura, Kohji Okamoto, Tadahiro Takada, et al.: Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis . JHepato‐Biliary‐Pancreatic Surg. 2018, 25:31-40. 10.1002/jhbp.509

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Gallstones disease. diagnosis and management of cholelithiasis, cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis,2014. Available at. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg188/resources/gallstone-disease-diagnosis-and-management-pdf35109819418309..

Publisher | Google Scholor - ashita Y, Takada T, Strasberg SM, et al.: TG13 surgical management of acute cholecystitis. JHepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013, 20:89-96. 10.1007/s00534-012-0567-x

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ansaloni L, Pisano M, Coccolini F, Peitzmann AB: Fingerhut A, Catena F, et al.2016 WSES guidelines on acute calculous cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016, 11:25. 10.1186/s13017-016-0082-5

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pang KW, Tan CH, Loh S, et al.: Outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis. World J Surg. 2016, 40:2735-2744. 10.1007/s00268-016-3585-z

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yu-Liang Hung , Chang-Mu Sung , Chih-Yuan Fu, et al. (ed): Management of Patients With Acute Cholecystitis After Percutaneous Cholecystostomy: From the Acute Stage to Definitive Surgical Treatment. 2021, 15:616320. 10.3389/fsurg.2021.616320

Publisher | Google Scholor - ocio Perez-Johnston , Amy R Deipolyi , Anne M Covey : Percutaneous Biliary Interventions. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018, 47:621-641. 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.04.008

Publisher | Google Scholor - Simorov A, Ranade A, Parcells J, et al.: Emergent cholecystostomy is superior to open cholecystectomy in extremely ill patients with acalculous cholecystitis: a large multicenter outcome study. Am. J. Surg. 2013, 206:935-940. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.019

Publisher | Google Scholor - Anderson JE, Inui T, Talamini MA, et al.: Cholecystostomy offers no survival benefit in patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis and severe sepsis and shock. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 190:517-521. 10.1016/j.jss.2014.02.043

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pomerantz BJ: Biliary tract interventions. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009, 12:162-70. 10.1053/j.tvir.2009.08.009

Publisher | Google Scholor - Picus D, Hicks ME, Darcy MD, et al.: Percutaneous cholecystolithotomy: analysis of results and complications in 58 consecutive patients. Radiology. 1992, 183:779-84. 10.1148/radiology.183.3.1533946

Publisher | Google Scholor - D’Agostino HB, vanSonnenberg E, Sanchez RB, et al.: Imaging of the percutaneous cholecystostomy tract: observations andutility. Radiology. 1991, 181:675-678. 10.1148/radiology.181.3.1947080

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hung YL, Chong SW, Cheng CT, et al.: Natural course of acute cholecystitis in patients treated with percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage without elective cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020, 24:772-9. 10.1007/s11605-019-04213-0

Publisher | Google Scholor - Noh SY, Gwon D Il, Ko GY, et al.: Role of percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis: clinical outcomes of 271 patients. Eur Radiol. 2018, 28:1449-55. 10.1007/s00330-017-5112-5

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wang CH, Wu CY, Yang JCT, et al.: Long-term outcomes of patients with acute cholecystitis after successful percutaneous cholecystostomy treatment and the risk factors for recurrence: a decade experience at a single center. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11:0148017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148017

Publisher | Google Scholor - Steven J Krohmer, Anil K Pillai, Carlos J Guevara, et al. (ed): Image-Guided Biliary Interventions: How to Recognize, Avoid, or Get Out of Troubl. 2018, 21:249-254.. 10.1053/j.tvir.2018.07.006

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hung Y-L, Chen H-W, Fu C-Y, et al.: Surgical outcomes of patients with maintained or removed percutaneous cholecystostomy before intended laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2020, 27:461-9. 10.1002/jhbp.740

Publisher | Google Scholor - Loftus TJ, Brakenridge SC, Moore FA, et al.: Routine surveillance cholangiography after percutaneous cholecystostomy delays drain removal and cholecystectomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 82:351-5. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001315

Publisher | Google Scholor - Park JKJK, Yang J Il, Wi JW, et al.: Long-term outcome and recurrence factors after percutaneous cholecystostomy as a definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019, 34:784-90. 10.1111/jgh.14611

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cha BH, Song HH, Kim YN, et al.: Percutaneous cholecystostomy is appropriate as definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis in critically ill patients: a single center, cross-sectional study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014, 63:32. 10.4166/kjg.2014.63.1.32

Publisher | Google Scholor