Case Report

Spontaneously Ruptured Bicornuate Uterus: A Near-Missed Case During Mid-Second-Trimester Pregnancy

- Misganaw Worku *

- Khadar Abdilahi

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Sidama Region, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Misganaw Worku, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Sidama Region, Ethiopia.

Citation: Worku M, Abdilahi K. (2024). Spontaneously Ruptured Bicornuate Uterus: A Near-Missed Case During Mid-Second-Trimester Pregnancy, Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(1):1-5. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.24.023

Copyright: © 2024 Misganaw Worku, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: October 26, 2023 | Accepted: December 13, 2023 | Published: January 02, 2024

Abstract

Bicornuate uterine rupture is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication during pregnancy, especially following previous normal vaginal deliveries when it is often misdiagnosed. This case study presents the clinical profile and management approach for a 35-year-old gravida 2 para 1 patient who was diagnosed with a spontaneously ruptured bicornuate uterus at 20 weeks of her second-trimester pregnancy. Laparotomy revealed a bicornuate uterus with a ruptured rudimentary horn and massive hemoperitoneum. This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis, prompt surgical intervention, and multidisciplinary collaboration to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes.

Keywords: uterine rupture; bicornuate uterus; mid-trimester

Introduction

A bicornuate uterus is a heart-shaped congenital uterine anomaly that occurs when two paramesonephric ducts fail to fuse completely during embryonic development. This results in a uterus with two horns or chambers separated by a septum. A bicornuate uterus can have different degrees of separation, ranging from a partial septum to complete division of the uterus and cervix. Although accurate prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies is not exactly known, it is stated to range between 0.5% and 5.5% in the general female population. Besides, bicornuate uterus accounts for one-quarter to two-fifths of Mullerian anomalies, with an overall estimated incidence of 0.1–0.6% [1-4].

A bicornuate uterus, which is estimated to have a live birth rate of 60% [3], may result in a number of complications during pregnancy such as recurrent miscarriage, preterm labor and delivery, fetal malpresentation, and, rarely uterine rupture. Uterine rupture, which is extremely rare but life-threatening complication of this aberrant uterus occurs during one of the trimesters of pregnancy or labor. This can lead to severe bleeding, shock, and fetal distress, posing a significant risk to both mother and fetus. Uterine rupture may be the result of restricted uterine expansion due to the fibrous band connecting the two uterine corpora [5]. It may also occur after pregnancy in the rudimentary horn of the bicornuate uterus, which is a smaller and less-developed part of the uterus. Moreover, a pregnancy in the rudimentary horn is very rare but may likely cause late first-trimester or second-trimester uterine rupture and often remains undiagnosed until it ruptures, with an estimated 50% risk of spontaneous rupture, making it a life-threatening entity [6-10].

Uterine anomalies during pregnancy are rare yet often go unnoticed in settings with a weak technical platform. In developing countries such as Ethiopia, pre-pregnancy checkup is very low; more than 50% of pregnant mothers book their first antenatal care late, after 4 months of gestational age, due to factors such as mothers’ educational level, place of residence, and financial constraints [11]. Hence, optimal diagnosis and management of a bicornuate uterus pregnancy event with such catastrophic obstetric complications may be delayed. This case study highlights the importance of considering the potential presentation of a spontaneously ruptured bicornuate uterus during pregnancy.

We report the case of a spontaneously ruptured bicornuate uterus during mid-trimester pregnancy, considering the rarity of this scenario.

Case Summary

W/ro MY, a 35-year-old G2P1 woman with 5 months of amenorrhea from Sidama, Ethiopia, who has a 10-year-old child, was transferred to Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital adult emergency outpatient department from a primary hospital for emergency laparotomy. The patient did not remember her last menstrual period and presented with lower abdominal pain for two weeks, which worsened in the last day. She had associated fatigability, light-headedness, vertigo, and shortness of breath. She had not yet started antenatal care and was referred from the primary hospital with a possible diagnosis of ruptured appendicitis and a second-trimester pregnancy. The patient had no history of vaginal bleeding or abdominal trauma. Her first pregnancy was uneventful for 9 months and ended with a normal vaginal delivery at the local health center, ten years ago. The patient had no history of any known medical illness or surgery. Additionally, she had been using hormonal contraceptives for five years with no menstrual abnormalities.

Upon clinical physical examination, the woman was acutely sick looking and in cardiorespiratory distress with blood pressure 85/60 mmHg, pulse rate 128 beats per minute, respiratory rate 28 breaths per minute, and peripheral oxygen saturation 81%. She had paper-white conjunctiva but with normal lung auscultation on examination. Her abdomen was diffusely distended and tender, with positive signs of fluid collection, and a 20-week-sized uterus was palpated. Vaginal examination showed that the cervix was closed with cervical motion tenderness and a bulged cul-de-sac. An emergency abdominal ultrasound was performed, which showed massive blood loss in the peritoneal cavity, an enlarged empty uterus, and an extrauterine dead fetus with a biparietal diameter (BPD) of 20 weeks situated in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. Her hematocrit was also found to be 7.5%, with hemoglobin of 2 g/dL.

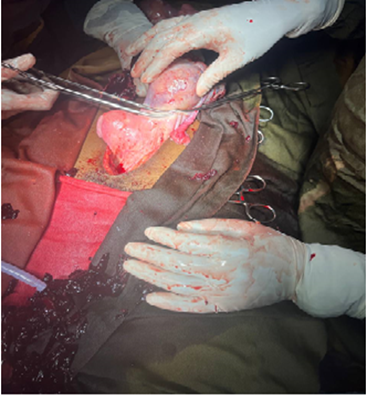

Thereafter, an abdominal pregnancy to rule out spontaneous second-trimester uterine rupture was considered as her diagnosis and laparotomy was planned urgently; meanwhile, giving due attention to her ABC of life, she was placed in the shock position and resuscitation initiated with intravenous crystalloid via double lines and face-mask oxygen; three units of cross-matched blood were prepared, and informed consent was obtained. The patient underwent laparotomy within 2 hours of arrival. Intraoperatively, approximately 4000 mL of hemoperitoneum was found and aspirated. A well-formed female abortus with free-floating placenta was extracted from the peritoneal cavity. During further exploration, the uterus was found to have two horns with more than 2 cm cleft between them. Both horns had anatomically attached ovaries and tubes. The right horn was intact and looked grossly healthy, whereas the left horn was severed and ruptured at the fundus, measuring 7 cm × 6 cm (Figure 1). The ruptured left horn communicated with the right horn at the anatomical junction between the body and lower segment, and they shared a single cervix. Hence, rudimentary horn resection was performed to remove the ruptured horn, repair the defect, and secure hemostasis, and tissue was subjected to histopathology. Blood transfusion was initiated and the abdomen was closed in layers. The patient awoke from anesthesia, spent one week on the wards, was discharged home after counseling to use contraception for at least one year, and had elective CS at 36-37 weeks of pregnancy.

Figure 1: The ruptured bicornuate uterus.

Figure 2: Resecting the ruptured horn.

Figure 3: The well-formed dead fetus.

Discussion

Uterine rupture in a bicornuate uterus during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy is rare; however, it can result in dangerous complications that can cause severe harm to both mother and baby. Symptoms can vary from mild, such as abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding, to severe, such as hypovolemic shock. It is important to diagnose this condition quickly and maintain a high level of suspicion in patients with a history of uterine abnormalities or previous uterine surgery. Moreover, it is noteworthy that spontaneous rupture of the unnoticed bicornuate uterus occurs in cases of acute abdomen and hemodynamic instability [10, 12-16]. In our case, an abdominal pregnancy was considered preoperatively.

A bicornuate uterus is a congenital malformation of the uterus with two horns and a septum dividing the cavity. Women with this condition continue to have normal pregnancies and deliveries [3]. There have also been cases of successful twin pregnancies in a bicornuate uterus [17, 18]. However, a bicornuate uterus can cause many complications and adverse outcomes during the pregnancy, such as recurrent pregnancy loss (25%), preterm birth (15–25%), cervical insufficiency (38%), and pregnancy in a rudimentary horn. A rudimentary horn is a small and underdeveloped part of the uterus that is at increased risk of rupture and may or may not communicate with the main cavity. Pregnancy in a rudimentary horn is very rare, occurring in approximately 1 in 400,000 women [15]; however, it needs to be treated promptly, considering the very high risk of rupture with pregnancy progress. In addition, the presence of a fibrous band between the two corpora is thought to restrict pregnancy horn expansion, leading to a high risk of rupture [10, 19-21].

The best way to diagnose a bicornuate uterus is to use a combination of hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, which are usually performed as part of infertility investigations [15]. However, as these anomalies are unnoticed in previously asymptomatic patients such as the current case, an incidental diagnosis is often made after emergency laparotomy. A rudimentary horn pregnancy can rupture because the malformed uterus cannot stretch sufficiently to accommodate a growing fetus. Rupture usually occurs in the late first or early to mid-second trimester, and often at the top of the uterus, unlike lower-segment rupture during labor.

When a bicornuate uterine rupture is diagnosed, immediate surgery is necessary to save the lives of the mother and/or baby [12]. A team of specialists, including an obstetrician, an anesthesiologist, and a neonatologist, should work together to manage such cases effectively. The recommended surgery may involve different techniques such as repair of the rupture, removal of the ruptured rudimentary horn, hysterectomy, stabilization of blood pressure and blood loss, and delivery and resuscitation of the baby if alive and viable. The ovary should be preserved on the same side if possible to maintain fertility potential [13, 22]. Before surgery, several factors should be considered, including gestational age, viability of the baby, potential complications, and the availability of resources. After surgery, the mother should be monitored closely for recovery, infection, bleeding, or uterine dehiscence. The baby should receive appropriate neonatal care if alive and viable. Long-term reproductive outcomes and the risk of recurrence of uterine rupture should also be discussed with the mother. Women who want to preserve fertility have a risk of recurrence between 4 and 19% in a subsequent pregnancy. Therefore, they should be advised to undergo cesarean delivery in all future pregnancies [12]. Our approach involved promptly stabilizing maternal hemodynamics through whole blood transfusion and fluid replacement therapy. Subsequently, exploratory laparotomy was performed to remove the ruptured left uterine horn and repair the uterus. We provided psychological support and contraceptive advice during postoperative management, as pregnancy is discouraged for at least one year after surgery [15].

Conclusion

A bicornuate uterus, a rare uterine anomaly, is associated with obstetric complications at different stages of pregnancy. In cases of acute abdominal pain and hypovolemia in mid-trimester pregnancies, a ruptured uterus should be considered as a possible diagnosis. Although screening for uterine anomalies is not given due attention in developing countries, it is commendable to advocate early initiation of ANC and consider proper uterine anatomic scanning for possible anomalies, particularly for women with pelvic complaints such as unexplained infertility. Screening for uterine anomalies should be included in prenatal reproductive health evaluation programs to reduce maternal mortality rates. Moreover, women who experience such a catastrophe should have psychosocial support and be given written recommendations for the timing and mode of delivery if they become pregnant.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

References

- Nahum GG. (1998). Uterine anomalies. How common are they, and what is their distribution among subtypes? The Journal of reproductive medicine, 43(10):877-887.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pfeifer SM, Attaran M, Goldstein J, Lindheim SR, Petrozza JC, Rackow BW, et al. (2021). ASRM müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertility and sterility, 116(5):1238-1252.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chan Y, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, Thornton J, Raine-Fenning N, Coomarasamy A. (2011). The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Human reproduction update, 17(6):761-771.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Suparman E. (2021). (Peer Review) Bicornuate Uterus with Previous C-Section: A Case Report.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saleem HA, Edweidar Y, Salim MA, Mahfouz IA. (2023). Mid-trimester spontaneous rupture of a bicornuate uterus: A case report. Case Reports in Women's Health, 39:00524.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kaur P, Panneerselvam D. (2020). Bicornuate uterus.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nelson R. (2022). Bicornuate uterus with second trimester fetal demise in a rudimentary horn. South African Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28(1):30-32.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Badeghiesh A, Kadour E, Baghlaf H, Dahan M. (2022). P-718 How do bicornuate uteri alter pregnancy, intra-partum and neonatal risks? A population-based study of more than 3-million deliveries and more than 6000 bicornuate uteri. Human Reproduction, 37(S1).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kaur M, Kaur M, Kaur P, Singh A, Tolia P. (2018). Pregnancy in a Non-Communicating Rudimentary Horn-Medical Emergency and A Near Miss. GMC Patiala Journal of Research and Medical Education, 1(2):116-118.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kurniawati EM, Indriati FM, Riskianto CR. (2022). A Rare Case of Spontaneous Uterine Rupture in Second Trimester Pregnancy with Bicornuate Uterus: A Case Report. Journal of Health Sciences, 15(01):32-38.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Haile RN. (2022). Time to first antenatal care booking and its determinants among pregnant women in Ethiopia: survival analysis of recent evidence from EDHS 2019. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1):1-11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tola EN. (2014). First trimester spontaneous uterine rupture in a young woman with uterine anomaly. Case reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tochie JN, Tcheunkam LW, Tchakounté C, Fobellah NN, Cumber SN. (2020). First-trimester rupture of a gravid bicornuate uterus after prior vaginal deliveries, simulating a ruptured ectopic pregnancy: a case report. Journal of Surgical Case Reports, 2020(10):366.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hefny AF, Kunhivalappil FT, Nambiar R, Bashir MO. (2015). A rare case of first-trimester ruptured bicornuate uterus in a primigravida. International journal of surgery case reports, 14:98-100.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh N, Singh U, Verma ML. (2013). Ruptured bicornuate uterus mimicking ectopic pregnancy: A case report. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 39(1):364-366.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Walsh CA, Baxi LV. (2007). Rupture of the primigravid uterus: a review of the literature. Obstetrical & gynecological survey, 62(5):327-334.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Moltot T, Lemma T, Silesh M, Sisay M, Tsegaw B. (2023). Successful post-term pregnancy in scared bicornuate uterus: case report. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 23(1):559.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arora M, Gupta N, Neelam, Jindal S. (2007). Unique case of successful twin pregnancy after spontaneous conception in a patient with uterus bicornis unicollis. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 276:193-195.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Agu P, Okaro J, Mbagwu U, Obi S, Ugwu E. (2012). Spontaneous rupture of gravid horn of bicornuate uterus at mid trimester-A case report. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 21(1):106-107.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nitzsche B, Dwiggins M, Catt S. (2017). Uterine rupture in a primigravid patient with an unscarred bicornuate uterus at term. Case reports in women's health, 15:1-2.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jayaprakash S, Muralidhar L, Sampathkumar G, Sexsena R. (2011). Rupture of bicornuate uterus. BMJ case reports.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Heinonen PK. (2000). Clinical implications of the didelphic uterus: long-term follow-up of 49 cases. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 91(2):183-190.

Publisher | Google Scholor