Research Article

Risk Factors and Prevention Methods of Breast Cancer among Women Residing in Southeast Nigeria

- E. I. Ezebuiro 1

- C. O. Onyemereze 2

- E. O. Ewenyi 3

- I. A. Onuah 4

- E. O. Ezirim 2

- E. M. Akwuruoha 2

- N. B. Zurmi 5

- O. R. Omole 6

- I. O. Abali 7

- A. I. Airaodion 8*

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Port-Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria.

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria.

3 School of Public Health, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

4 Department of Surgery, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria.

5School of Public Health, Texila American University, Guyana.

6Department of Nursing, Coventry University, United Kingdom.

7Department of Surgery, Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria.

8Department of Biochemistry, Lead City University, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria.

*Corresponding Author: A. I. Airaodion, Department of Biochemistry, Lead City University, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria.

Citation: E.I. Ezebuiro, C.O. Onyemereze, E.O. Ewenyi, I.A. Onuah, A.I. Airaodion, et, al. (2024). Risk Factors and Prevention Methods of Breast Cancer among Women Residing in Southeast Nigeria. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(6):1-14. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.24.050

Copyright: © 2024 A.I. Airaodion, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: June 06, 2024 | Accepted: June 22, 2024 | Published: June 27, 2024

Abstract

Background: Breast cancer is a significant health issue in Southeast Nigeria, contributing to high morbidity and mortality rates among women. This study aims to identify the risk factors and prevention methods of breast cancer in this region.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive survey was conducted among women aged 18 years and above residing in Southeast Nigeria. Stratified sampling was used to ensure representation from both urban and rural areas. A total of 360 participants were selected through a multi-stage sampling process involving the random selection of states, local government areas (LGAs), hospitals, and participants. Data were gathered using a structured questionnaire.

Results: The majority of participants were aged 30-39 years (52.50%), had secondary education (58.89%), and were married (84.17%). Key findings included that 16.39% had been diagnosed with breast cancer, 16.94% had a family history of breast cancer, and 12.12% had diabetes. Lifestyle factors revealed low alcohol consumption and smoking rates but inconsistent exercise habits. Only 38.33% performed regular breast self-examinations, and 22.50% had ever had a mammogram. Awareness of breast cancer risk factors was low, with only 18.61% fully aware. Access to healthcare was limited, with 70.56% lacking access to breast cancer screening services.

Conclusion: The study highlights significant gaps in awareness, screening, and prevention of breast cancer among women in Southeast Nigeria. Interventions focusing on education, improved access to screening services, and addressing cultural barriers are essential to enhance breast cancer prevention and early detection in this region.

Keywords: breast cancer; risk factors; prevention methods; southeast Nigeria; women’s health; screening; awareness

Introduction

Breast cancer remains a significant global health concern, representing the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women and a leading cause of cancer-related mortality. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer accounts for approximately 15% of all cancer deaths among women globally [1]. Despite advances in diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, the incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer continue to rise, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2]. This trend underscores the necessity for targeted research to identify region-specific risk factors and effective prevention strategies, particularly in areas with distinct socio-cultural and economic contexts, such as Southeast Nigeria. The epidemiology of breast cancer in Nigeria reflects a troubling pattern of late-stage diagnosis and high mortality rates. Studies indicate that breast cancer is the most common cancer among Nigerian women, with increasing incidence rates reported over the past few decades [3]. The high mortality rate is often attributed to factors such as delayed presentation, limited access to healthcare facilities, and inadequate cancer awareness [4]. In Southeast Nigeria, these challenges are compounded by cultural beliefs and practices that influence health-seeking behaviours and the acceptance of medical interventions [5].

Identifying the risk factors for breast cancer is critical for developing effective prevention strategies. Globally, several risk factors have been well-documented, including genetic predisposition, reproductive history, hormonal factors, lifestyle choices, and environmental exposures [6]. However, the relevance and impact of these factors can vary significantly across different populations. In Southeast Nigeria, specific risk factors have been identified through various studies. Genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, are known to significantly increase breast cancer risk [7]. Reproductive factors, including early menarche, late menopause, nulliparity, and use of hormonal contraceptives, have also been implicated [5]. Additionally, lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and obesity have been shown to influence breast cancer risk [8]. Socio-cultural factors play a crucial role in the epidemiology and management of breast cancer in Southeast Nigeria. Cultural beliefs and stigma associated with cancer can lead to delays in seeking medical help and adherence to traditional healing practices [9]. Furthermore, gender roles and expectations may affect women's access to healthcare services and their ability to make autonomous health decisions [10]. These socio-cultural dynamics necessitate culturally sensitive approaches in breast cancer prevention and education programs.

Prevention and early detection of breast cancer are vital components of reducing the burden of the disease. Primary prevention strategies include lifestyle modifications, such as maintaining a healthy diet, regular physical activity, and avoiding alcohol and tobacco use [11]. Secondary prevention focuses on early detection through screening methods like mammography, clinical breast examination (CBE), and breast self-examination (BSE) [12]. In Southeast Nigeria, the implementation of these strategies faces several obstacles, including limited access to screening facilities, lack of trained healthcare professionals, and financial constraints [13]. Promoting awareness and education about breast cancer, alongside improving healthcare infrastructure and accessibility, are essential steps towards enhancing early detection and reducing mortality rates. Recent advances in breast cancer research offer promising directions for improving outcomes. Molecular profiling and personalized medicine approaches are gaining traction, allowing for more tailored treatment regimens based on individual genetic and molecular characteristics [14]. However, the application of these advanced technologies in LMICs, including Southeast Nigeria, remains limited due to resource constraints. There is also a pressing need for more region-specific research to understand the unique risk factors and effective prevention methods for breast cancer in Southeast Nigeria. Comprehensive studies that integrate epidemiological data, socio-cultural analyses, and healthcare accessibility assessments are crucial for developing targeted interventions.

Research Methodology

Study Design

A cross-sectional descriptive survey was conducted to assess the risk factors and prevention methods of breast cancer among women in Southeast Nigeria.

Study Area

Southeast Nigeria, comprising states such as Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo, faces significant health challenges, including breast cancer. Breast cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among women in this region. Several factors contribute to this high burden, including limited access to healthcare facilities, lack of awareness about breast cancer symptoms, and cultural stigmas that delay diagnosis and treatment. Healthcare infrastructure in Southeast Nigeria is relatively underdeveloped, with many rural areas lacking adequate medical services. This results in late-stage presentations of breast cancer, which significantly reduces survival rates. Efforts to improve early detection through awareness campaigns and mobile screening units are vital. Additionally, addressing cultural barriers and educating women on the importance of regular breast self-examinations and seeking prompt medical attention can improve outcomes.

Population and Sampling

Target Population

The target population comprised women aged 18 years and above residing in Southeast Nigeria.

Sampling Method

A stratified sampling method was employed to ensure representation from both urban and rural areas within the southeast states. The steps involved were:

Selection of States: Three states were randomly selected from the five states in Southeast Nigeria.

Selection of Local Government Areas (LGAs): Six LGAs were selected from each state, with an equal representation of urban and rural areas (three urban and three rural LGAs per state).

Selection of Hospitals: Two general hospitals were randomly chosen from each LGA.

Selection of Participants: From each hospital, ten participants were selected, resulting in a total sample size of 360 women.

Data Collection

Instrument

Data was collected using a structured questionnaire developed by the research team. The questionnaire was divided into different sections covering socio-demographic information, medical history, lifestyle factors, breast cancer screening and prevention, access to healthcare, awareness of breast cancer risk factors, and attitudes towards breast cancer prevention.

Procedure

Pre-testing: The questionnaire was pre-tested on a small sample of women to ensure clarity and appropriateness of the questions.

Training of Data Collectors: Data collectors were trained on the objectives of the study, ethical considerations, and the administration of the questionnaire.

Data Collection: Face-to-face interviews were conducted with the participants in their local languages or English, depending on their preference.

Variables

Dependent Variables

Risk Factors: Age at first menstrual period, age at first childbirth, family history of breast cancer, personal history of other cancers, history of chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), lifestyle factors (alcohol consumption, smoking, exercise, diet), and use of hormonal contraceptives.

Prevention Methods: Awareness and practice of breast self-examination, mammography, maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding smoking, limiting alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and healthy diet.

Independent Variables

Socio-Demographic Factors: Age, educational level, marital status, employment status, and residence (urban/rural).

Access to Healthcare: Frequency of healthcare visits, availability of breast cancer screening services, barriers to accessing screening services.

Awareness and Attitudes: Awareness of breast cancer risk factors, belief in the preventability of breast cancer, importance of breast cancer prevention, and willingness to participate in prevention programs.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages to summarize the socio-demographic characteristics, medical history, lifestyle factors, screening and prevention methods, access to healthcare, awareness, and attitudes towards breast cancer prevention. Cross-tabulations were used to explore associations between the dependent and independent variables.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Participant anonymity was ensured by assigning codes to the questionnaires and keeping all information confidential. The study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committees in each of the selected states.

Results

In terms of age, most participants were between 30-39 years (52.50%), with smaller groups under 20 (5.28%), 20-29 (23.89%), and 40 and above (18.33%). A majority had secondary education (58.89%), while others had primary (8.89%), tertiary education (29.17%), or no formal education (3.06%). Marital status was predominantly married (84.17%), with single (10.00%) and divorced/widowed (5.83%) individuals making up the rest. Employment status showed that 56.94% were self-employed, 25.83% unemployed, and 17.22% employed, with no retirees. Residency was evenly split between rural and urban areas (50.00 Percentage each) (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-Demographic Information of Participants.

| Socio-Demographic Information | Frequency (n = 360) | Percentage (%) |

| Age (in Years) | ||

| Less than 20 | 19 | 5.28 |

| 20 – 29 | 86 | 23.89 |

| 30 – 39 | 189 | 52.50 |

| 40 and above | 66 | 18.33 |

| Educational Level | ||

| No formal Education | 11 | 3.06 |

| Primary Education | 32 | 8.89 |

| Secondary Education | 212 | 58.89 |

| Tertiary Education | 105 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 36 | 10.00 |

| Married | 303 | 84.17 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 21 | 5.83 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 62 | 17.22 |

| Self-Employed | 205 | 56.94 |

| Unemployed | 93 | 25.83 |

| Retiree | 00 | |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 180 | 50.00 |

| Urban | 180 | 50.00 |

Regarding medical history, 16.39% had been diagnosed with breast cancer, and 16.94% reported a family history of it. A small portion had other cancers (8.89%). Among other health conditions, hypertension (16.25%) and diabetes (12.12%) were most common, while 63.64% reported no such conditions (Table 2).

Table 2: Medical History of Participants.

| Variables | Frequency (n = 360) | Percentage (%) |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with breast cancer? | ||

| Yes | 59 | 16.39 |

| No | 301 | 83.61 |

| Do you have a family history of breast cancer? | ||

| Yes | 61 | 16.94 |

| No | 299 | 83.06 |

| Have you ever had any other type of cancer? | ||

| Yes | 32 | 8.89 |

| No | 328 | 91.11 |

| *Do you have a history of any of the following conditions? (Check all that apply) (n = 363) | ||

| Diabetes | 44 | 12.12 |

| Hypertension | 59 | 16.25 |

| Obesity | 29 | 7.99 |

| None | 231 | 63.64 |

* Signifies multiple responses

Lifestyle factors revealed that a significant majority never consumed alcohol (75.00%) or smoked (89.72%). Exercise habits varied, with 60.83% exercising occasionally and smaller percentages exercising regularly (12.50%) or daily (3.06%). A substantial number (77.50%) regularly consumed fruits and vegetables. Over half (55.28%) used hormonal contraceptives. The majority had their first menstrual period between ages 15-17 (56.11%) and had children (88.33%), with most having their first child at 25-29 years old (61.00%). Breastfeeding was prevalent among mothers (86.67%) (Table 3).

Table 3: Lifestyle Factors of Participants.

| Variables | Frequency (n = 360) | Percentage (%) |

| How often do you consume alcohol? | ||

| Daily | 00 | 0.00 |

| Regularly | 00 | 0.00 |

| Occasionally | 28 | 7.78 |

| Rarely | 61 | 16.94 |

| Never | 270 | 75.00 |

| Do you smoke? | ||

| Yes | 13 | 3.61 |

| No | 323 | 89.72 |

| Quit | 24 | 6.67 |

| How often do you exercise? | ||

| Daily | 11 | 3.06 |

| Regularly | 45 | 12.50 |

| Occasionally | 219 | 60.83 |

| Rarely | 72 | 20.00 |

| Never | 13 | 3.61 |

| Do you regularly consume fruits and vegetables? | ||

| Yes | 279 | 77.50 |

| No | 81 | 22.50 |

| Do you use hormonal contraceptives? | ||

| Yes | 199 | 55.28 |

| No | 161 | 44.72 |

| At what age did you have your first menstrual period? | ||

| Under 12 | 9 | 2.50 |

| 12 – 14 | 138 | 38.33 |

| 15 – 17 | 202 | 56.11 |

| 18 and above | 11 | 3.05 |

| Have you had children? | ||

| Yes | 318 | 88.33 |

| No | 42 | 11.67 |

| If yes, at what age did you have your first child? | ||

| Under 20 | 24 | 7.55 |

| 20 – 24 | 51 | 16.04 |

| 25 – 29 | 194 | 61.00 |

| 30 and above | 49 | 15.41 |

| Have you breastfed your children? | ||

| Yes | 312 | 86.67 |

| No | 6 | 1.67 |

| Not Applicable | 42 | 11.67 |

Screening and prevention showed that 61.11% had heard of mammograms, but only 22.50% had ever had one, with annual screening being rare (25.93%). Regular breast self-examinations were performed by 38.33%, but many did so rarely (42.03%). Awareness of breast cancer prevention methods was low (36.11%), and common barriers included lack of awareness (51.11%) and financial constraints (15.56%). Information sources were mainly internet/social media (48.61%) and healthcare providers (26.67%) (Table 4).

Table 4: Screening and Prevention of Breast Cancer.

| Variables | Frequency (n = 360) | Percentage (%) |

| Have you ever heard of a mammogram? | ||

| Yes | 220 | 61.11 |

| No | 140 | 38.89 |

| Have you ever had a mammogram? | ||

| Yes | 81 | 22.50 |

| No | 279 | 77.50 |

| If yes, how often do you get a mammogram? | ||

| Annually | 21 | 25.93 |

| Every two years | 08 | 9.88 |

| Occasionally | 16 | 19.75 |

| Only once | 36 | 44.44 |

| Do you perform regular breast self-examinations? | ||

| Yes | 138 | 38.33 |

| No | 222 | 61.67 |

| If yes, how often? | ||

| Monthly | 38 | 27.54 |

| Every few months | 23 | 16.67 |

| Annually | 19 | 13.77 |

| Rarely | 58 | 42.03 |

| Do you know about any breast cancer prevention methods? | ||

| Yes | 130 | 36.11 |

| No | 230 | 63.89 |

| *If yes, please specify which methods you are aware of. (Select all that apply) (n = 773) | ||

| Regular screening (mammograms) | 220 | 28.46 |

| Preventive medications | 7 | 0.91 |

| Maintaining a healthy weight | 68 | 8.80 |

| Avoiding smoking | 74 | 9.57 |

| Limiting alcohol consumption | 82 | 10.61 |

| Regular exercise | 101 | 13.07 |

| Healthy diet | 123 | 15.91 |

| Breast self-examinations | 98 | 12.68 |

| Other | 00 | 0.00 |

| What are the Barriers to Breast Cancer Screening? | ||

| Lack of awareness | 184 | 51.11 |

| Fear of diagnosis | 44 | 12.22 |

| Financial constraints | 56 | 15.56 |

| Cultural beliefs | 11 | 3.06 |

| Accessibility issues | 65 | 18.06 |

| What are your sources of information on breast cancer prevention? (Check all that apply) | ||

| Healthcare providers | 96 | 26.67 |

| Internet/Social media | 175 | 48.61 |

| TV/Radio | 51 | 14.17 |

| Friends/Family | 32 | 8.89 |

| Other | 06 | 1.67 |

* Signifies multiple responses

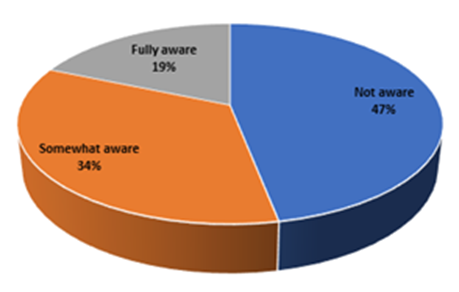

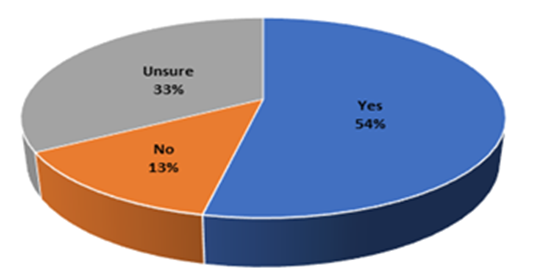

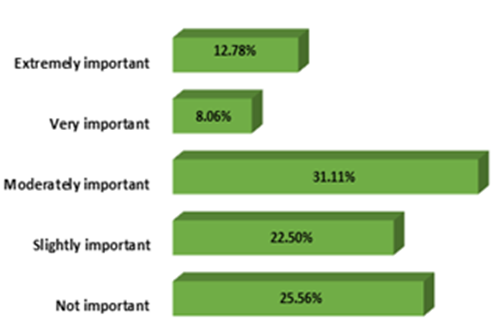

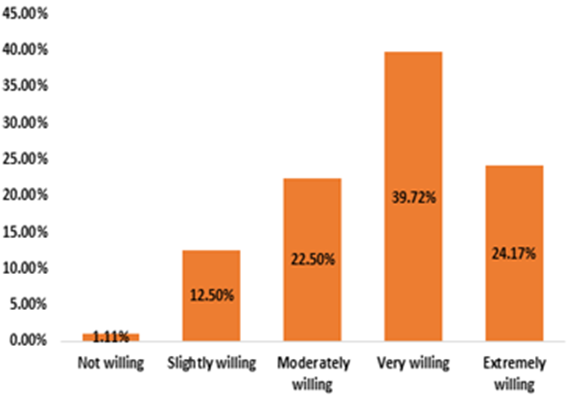

Awareness of breast cancer risk factors was limited, with 46.94% not aware and only 18.61% fully aware (Figure 1). In terms of healthcare access, regular check-ups were infrequent, with 66.39% visiting a provider only when sick. Access to breast cancer screening services was limited, with 70.56% lacking access, mainly due to lack of facilities (20.98%) and high costs (30.24%). Beliefs about breast cancer prevention varied, with 53.33 Percentage believing it can be prevented, while 33.33% were unsure (Figure 2). Attitudes towards breast cancer prevention showed that 31.11% considered it moderately important, while 25.56% found it not important (Figure 3). Willingness to participate in prevention programs was high, with 39.72% very willing and 24.17% extremely willing (Figure 4).

Figure 1: Awareness of Breast Cancer Risk Factors.

Table 5: Access to Healthcare.

| Variables | Frequency (n = 360) | Percentage (%) |

| How often do you visit a healthcare provider for a check-up? | ||

| Regularly (at least once a year) | 74 | 20.56 |

| Occasionally (once every few years) | 47 | 13.06 |

| Rarely (only when sick) | 239 | 66.39 |

| Never | 00 | 0.00 |

| Do you have access to breast cancer screening services in your area? | ||

| Yes | 106 | 29.44 |

| No | 254 | 70.56 |

| *If no, what are the main barriers to accessing these services? (Select all that apply) (n = 367) | ||

| Lack of facilities | 77 | 20.98 |

| High cost | 111 | 30.24 |

| Lack of awareness | 131 | 35.69 |

| Cultural beliefs | 37 | 10.08 |

| Fear of diagnosis | 11 | 3.00 |

| Other | 00 | 0.00 |

* Signifies multiple responses

Figure 2: Belief in the Prevention of Breast Cancer.

Figure 3:Attitude towards Breast Cancer Prevention.

Figure 4: Willingness to Participate in Breast Cancer Prevention Programs.

Discussion

The socio-demographic profile of the participants in this study reveals significant insights into the population's composition. The majority of participants fall within the age range of 30-39 years (52.50%), followed by 20-29 years (23.89%), indicating a predominantly young adult population. This aligns with the age distribution patterns observed in other studies conducted in developing regions, where younger populations are often more prevalent due to higher birth rates and lower life expectancy compared to developed countries [15]. Educational attainment shows that a significant proportion of participants have completed secondary education (58.89%), with a considerable number having attained tertiary education (29.17%). This level of education is higher compared to some other studies conducted in similar settings, which often report lower levels of educational attainment among women [16]. Higher education levels are crucial as they are associated with better health awareness and utilization of preventive health services. Marital status indicates that a vast majority (84.17%) of the participants are married, which is consistent with cultural norms in many parts of Nigeria where marriage is a common institution among adults. Employment status reveals that more than half of the participants are self-employed (56.94%), reflecting the economic structure of the region where informal sector employment is predominant [17]. The equal distribution between rural and urban residents (50

Conclusion

The study highlights significant gaps in awareness, screening practices, and healthcare access related to breast cancer among women in Southeast Nigeria. Addressing these through targeted education, improving healthcare infrastructure, and culturally sensitive interventions could enhance early detection and prevention efforts.

Declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest in relation to this study.

Authors’ Declaration

The authors hereby declare that the work presented in this article is original and that any liability for claims relating to the content of this article will be borne by them.

Funding

The research did not receive any funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. There were no sponsors other than the authors.

References

- World Health Organization. (2021). Breast cancer: prevention and control. WHO.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6):394-424.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jedy-Agba, E., Curado, M. P., Ogunbiyi, O., Oga, E., Fabowale, T., Igbinoba, F., & Afolayan, E. A. (2022). Cancer incidence in Nigeria: A report from population-based cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiology, 36(5):e271-e278.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Oluwatosin, O. A., & Oladepo, O. (2016). Knowledge of breast cancer and its early detection measures among rural women in Akinyele Local Government Area, Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Cancer, 6:271.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Okobia, M. N., Bunker, C. H., Zmuda, J. M., Kammerer, C. M., Vogel, V. G., Uche-Nwachi, I. A., & Ferrell, R. E. (2016). Case-control study of risk factors for breast cancer in Nigerian women. International Journal of Cancer, 119(9):2179-2185.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. (2019). Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: Individual participant meta-analysis, including 118,964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. The Lancet Oncology, 20(1):103-116.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akinde, O. R., Adedeji, O. A., & Coker, O. O. (2015). Cancer mortality pattern in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Cancer Epidemiology, 842032.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ogundiran, T. O., Huo, D., Adenipekun, A., Campbell, O., Oyesegun, R., Akang, E., & Olopade, O. I. (2022). Case-control study of body size and breast cancer risk in Nigerian women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176(11):986-993.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ajekigbe, A. T. (2021). Fear of mastectomy: The most common factor responsible for late presentation of carcinoma of the breast in Nigeria. Clinical Oncology, 3(2):78-80.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ibrahim, N. A., & Oludara, M. A. (2022). Socio-demographic factors and reasons associated with delay in breast cancer presentation: A study in Nigerian women. Breast, 21(3):416-418.

Publisher | Google Scholor - American Cancer Society. (2020). Breast cancer facts & figures 2019-2020. American Cancer Society.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saslow, D., Boetes, C., Burke, W., Harms, S., Leach, M. O., Lehman, C. D., & Smith, R. A. (2017). American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 57(2):75-89.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sambo, H. B., Samaila, M. O. A., Mbah, H. A., & Adamu, M. (2022). A histopathological analysis of malignant breast tumors at a tertiary hospital in North-Western Nigeria. Journal of Surgical Technique and Case Report, 4(2):98-102.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Koboldt, D. C., Fulton, R. S., McLellan, M. D., Schmidt, H., Kalicki-Veizer, J., McMichael, J. F., & Mardis, E. R. (2022). Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 490(7418):61-70.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Unger-Saldaña, K. (2014). Challenges to the early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in developing countries. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5(3):465-477.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Brinton, L. A., Figueroa, J. D., Awuah, B., Yarney, J., Wiafe, S., Wood, S. N., & Ansong, D. (2014). Breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 144(3):467-478.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adewumi, A. A., Kolapo, K. S., & Akpan, I. O. (2018). Socioeconomic factors influencing cancer diagnosis in Nigeria. Journal of Health and Medical Sciences, 3(2):45-52.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M., ... & Bray, F. (2015). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer, 136(5):E359-E386.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Cancer Research Fund. (2018). Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Breast Cancer. Continuous Update Project Expert Report.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Health Organization. (2020). Global breast cancer initiative implementation framework: A step-by-step guide to strengthening early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer. Geneva: WHO.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Terry, P. D., & Rohan, T. E. (2022). Cigarette smoking and the risk of breast cancer in women: a review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 11(10): 953-971.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Monninkhof, E. M., Elias, S. G., Vlems, F. A., van der Tweel, I., Schuit, A. J., Voskuil, D. W., & van Leeuwen, F. E. (2017). Physical activity and breast cancer: a systematic review. Epidemiology, 18(1):137-157.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Smith-Warner, S. A., Spiegelman, D., Yaun, S. S., Adami, H. O., Beeson, W. L., van den Brandt, P. A., ... & Willett, W. C. (2021). Intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. JAMA, 285(6):769-776.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hunter, D. J., Spiegelman, D., Adami, H. O., Beeson, L., van den Brandt, P. A., Folsom, A. R., & Willett, W. C. (2020). Non-dietary factors as risk factors for breast cancer in women: a review of the evidence. Environmental Health Perspectives, 108(S3):563-568.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kelsey, J. L., Gammon, M. D., & John, E. M. (2023). Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiologic Reviews, 15(1):36-47.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bernier, M. O., Plu-Bureau, G., Bossard, N., Ayzac, L., & Thalabard, J. C. (2020). Breastfeeding and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of published studies. Human Reproduction Update, 6(4):374-386.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adebamowo, C. A., Ogundiran, T. O., Adenipekun, A. A., Oyesegun, R. A., Campbell, O. B., Akang, E. E., ... & Shokunbi, W. A. (2023). Waist-hip ratio and breast cancer risk in urbanized Nigerian women. Breast Cancer Research, 5(2): R18.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pisa, P. T., Kruger, H. S., Vorster, H. H., & Margetts, B. M. (2022). Association between dietary habits and cancer risk in black South Africans: a case-control study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(11):1282-1290.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adebamowo, C. A., Ogundiran, T. O., & Adenipekun, A. (2023). Obesity and height in urban Nigerian women: relationship with breast cancer risk. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 129(9):559-565.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ng’ang’a, A., Nyaberi, Z., & Ogollah, R. (2018). Knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening among women in Kenya. African Health Sciences, 18(2):275-285.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Opoku, S. Y., Benwell, M., & Yarney, J. (2022). Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviour, and breast cancer screening practices in Ghana, West Africa. Pan African Medical Journal, 11:28.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akinola, M. A., Oluwatosin, O. A., & Titiloye, M. A. (2021). Breast cancer screening practices among women in Nigeria. Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 3(1):12-18.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Getu, M. A., Kebede, A. G., & Tura, A. K. (2019). Breast cancer awareness and practice of breast self-examination among women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of Cancer Research and Treatment, 7(3):53-58.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wang, D., Ji, S., Wu, L., & Zhang, J. (2014). Barriers to breast cancer screening among women in a rural area of China: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 4(8):e005119.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Moodley, J., Cairncross, L., Naiker, T., & Constant, D. (2018). From symptom discovery to treatment - women’s pathways to breast cancer care: A cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer, 18(1):312.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rains, S. A. (2018). Health information seeking and the World Wide Web: Applications for cancer education and control. Cancer Education and Prevention, 14(2):110-119.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akarolo-Anthony, S. N., Ogundiran, T. O., & Adebamowo, C. A. (2020). Emerging breast cancer epidemic: evidence from Africa. Breast Cancer Research, 12(4):S8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Oche, M. O., & Ayodele, S. O. (2022). Breast cancer awareness and screening practices among women in Sokoto, Nigeria: a survey. International Journal of Women's Health, 4:127-134.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ezeome, E. R., & Ezugwu, F. O. (2014). Attitude and practice of breast self-examination among female students of a Nigerian tertiary institution. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics, 10(3):695.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nwafor, A., & Imman, S. (2016). Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among female non-medical students in a tertiary institution in South-South Nigeria. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 8(1):1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adusei, B., & Osei, E. (2020). Awareness and perception of breast cancer screening among women in Ghana. Journal of Cancer Education, 35(4):654-662.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akhigbe, A. O., & Omuemu, V. O. (2019). Knowledge, attitudes and practices of breast cancer screening among female health workers in a Nigerian urban city. BMC Cancer, 9: 203.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Smith, R. A., Cokkinides, V., Brooks, D., Saslow, D., & Brawley, O. W. (2021). Cancer screening in the United States, 2021: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(2):1-23.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muthoni, A., & Miller, A. N. (2018). An exploration of rural and urban Kenyan women's knowledge and attitudes regarding breast cancer and breast cancer early detection measures. Health Care for Women International, 39(7):734-747.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nwozor, C. M., & Oragudosi, A. L. (2020). Awareness and utilization of breast cancer screening methods among female undergraduate students in a Nigerian university. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 23(1):75-80.

Publisher | Google Scholor