Research Article

Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Women After Miscarriage in Quetta City

- Nida Tabassum Khan *

- Muzhgan Saadat

Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Life Sciences & Informatics, Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and Management Sciences, Takatu Campus, Airport Road, Quetta, Balochistan.

*Corresponding Author: Nida Tabassum Khan, Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Life Sciences & Informatics, Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and Management Sciences, Takatu Campus, Airport Road, Quetta, Balochistan.

Citation: Khan N T, Saadat M. (2024). Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Women After Miscarriage in Quetta City, 2023. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(5):1-9. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.24.044

Copyright: © 2024 Nida Tabassum Khan, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: May 03, 2024 | Accepted: May 24, 2024 | Published: June 03, 2024

Abstract

Current study concludes that the prevalence of PTSD in women who had experienced miscarriage is considerably moderate i.e., 41%. Loss of pregnancy as a result of miscarriage may cause many undesirable psychological reactions in these women, including the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Its consequences are often an important clinical problem, which entails a variety of complications such as symptoms of avoidance, reexperiencing, increased arousal, anxiety and depression that may affect the overall functioning and mental health of a women. Our study also depicted that the severity of PTSD symptoms in women who had suffered from miscarriage is also associated with the duration and number of miscarriages. it is reported that the women who had suffered miscarriage twice had higher results of depression and anxiety intensity than the women who miscarried once resulting in transition from mild to moderate PTSD and even to severe levels as a consequence. Other triggering factors may include personality factors (neuroticism), sociodemographic factors (low education, non-supportive partner/in-laws, society pressure etc), age, previous losses (regardless of maternal status), childlessness and fertility problems. Consequently, understanding the type and frequency of emotional responses to miscarriage is therefore essential to target appropriate support, thus minimising symptoms of PTSD in long-term care.

Keywords: post-traumatic; miscarriage; depression; anxiety; psychological trauma

Introduction

Pregnancy misfortune is a typical issue, with miscarriages assessed to influence 25% of women who have been pregnant by the age of 39 years and ectopic pregnancy happening in roughly 1% of pregnancies [1]. There is an extension for long-term emotional impact but nonetheless, by and large, this aspect has been neglected. Mirroring this, it was minimal viewed as in the literature until the 1990s. Early studies focused on sorrow, which is certainly not a discrete mental diagnosis and is variably characterized [2]. However, from that point forward, research in the field has multiplied, with various sizeable examinations evaluating for mental analyses (nervousness, discouragement and PTSD) following pregnancy loss [3]. These examinations have shown that women appear to be at very significant risk of mental morbidity following unnatural birth cycle (miscarriage), with up to 41% self-reported anxiety, 36

Materials and Methods

This study is a cross sectional study involving 100 married women (Sample size =100) who had recently suffered from miscarriage. The participants were selected at random and participation was voluntarily with informed consent. Subjects were assessed with a Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) to approximate the prevalence of PTSD related to miscarriage among married females. Data was collected from different hospitals such as Saiban family hospital, Zoya hospital (located in Satellite Town, Quetta, Balochistan), relatives, family, friends, neighbors etc.

Inclusion criteria

- Married women who had suffered from miscarriage or perinatal loss recently within the time period of 6 months regardless of their previous miscarriages

- Having any one or two PTSD symptoms persistent for a month or more

Exclusion criteria

- Married women who had not experienced pregnancy loss ever

- Women who had experienced miscarriages before but at the time of interview were pregnant

- Women who were infertile and cannot bear offspring’s.

Assessment of Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to miscarriage was achieved with the help of CAPS scale [19] which exhibited intensity scales for the symptoms that compose a diagnosis and severity of PTSD. The CAPS was used in this study to assess recent rather than lifetime symptoms of PTSD.

CAPS consisted of two sections

Section 1- Personal data i.e., age, number of children, partners/in-laws’ behavior, education etc.

Section 2- Specialty questions about PTSD which includes questions related to symptoms of re-experiencing (e.g., recurrent thoughts, nightmares, flashbacks), avoidance (e.g., avoiding cues and thoughts related to the trauma, withdrawal from others, restricted affect) and increased arousal (e.g., insomnia, irritability, concentration problems, hypervigilance) following exposure to a traumatic event etc.

CAPS scale uses cutoff scoring

- 0-10 = Asymptomatic/few symptoms

- 11 - 22 = Mild PTSD

- 23 - 34 =Moderate PTSD

- 35 - 46 =Severe PTSD

- ≥ 47 = Extreme PTSD

Statistical analysis of the data was achieved using Microsoft excel 2013.

Results

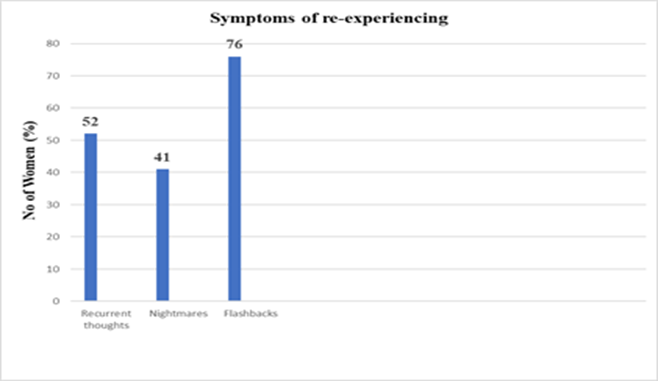

Table 1 and Graph 1 depicts the symptoms of re-experiencing among married women who had suffered from miscarriage

Table 1: Symptoms of re-experiencing among women who had suffered from miscarriage

| S.no | Symptoms of re-experiencing | No of Women (%) (n=100) |

| 1 | Recurrent thoughts | 52 |

| 2 | Nightmares | 41 |

| 3 | Flashbacks | 76 |

Graph 1: Symptoms of re-experiencing among women who had suffered from miscarriage

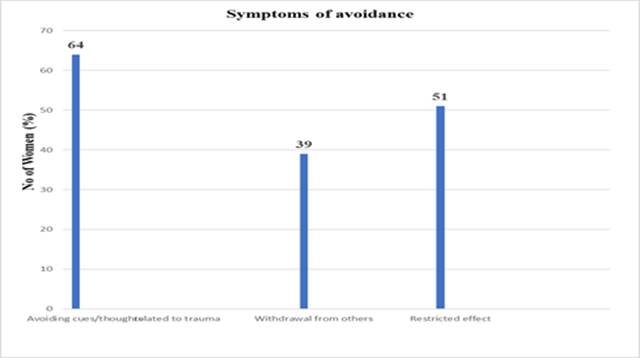

Table 2 and Graph 2 depicts the Symptoms of avoidance among married women who had suffered from miscarriage

Table 2: Symptoms of avoidance among women who had suffered from miscarriage.

| S.no | Symptoms of avoidance | No of Women (%) (n=100) |

| 1 | Avoiding cues/thoughts related to trauma | 64 |

| 2 | Withdrawal from others | 39 |

| 3 | Restricted effect | 51 |

Graph 2: Symptoms of avoidance among women who had suffered from miscarriage.

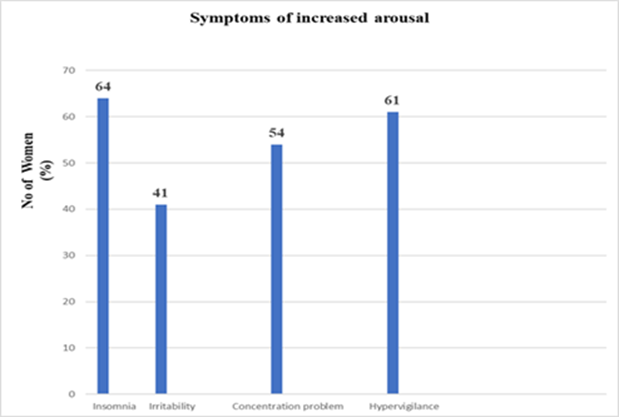

Symptoms of increased arousal among married women who had suffered from miscarriage were given in Table 3 and Graph 3.

Table 3: Symptoms of increased arousal among women who had suffered from miscarriage

| S.no | Symptoms of increased arousal | No of Women (%) (n=100) |

| 1 | Insomnia | 64 |

| 2 | Irritability | 41 |

| 3 | Concentration problem | 54 |

| 4 | Hypervigilance | 61 |

Graph 3: Symptoms of increased arousal among women who had suffered from miscarriage.

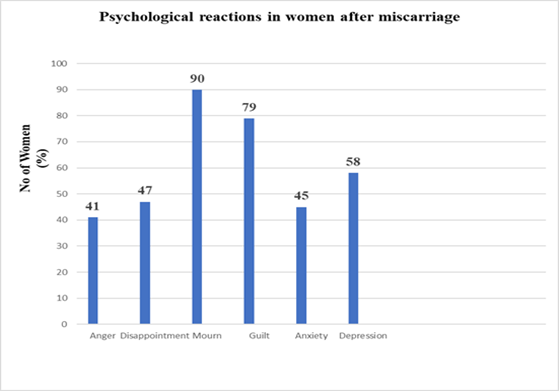

Psychological reactions in women after miscarriage were given in Table 4 and Graph 4.

Table 4: Psychological reactions in women after miscarriage

| S.no | Psychological reactions | No of women (%) (n=100) |

| 1 | Anger | 41 |

| 2 | Disappointment | 47 |

| 3 | Sadness/crying (Mourn) | 90 |

| 4 | Guilt | 79 |

| 5 | Anxiety | 45 |

| 6 | Depression | 58 |

Graph 4: Psychological reactions in women after miscarriage

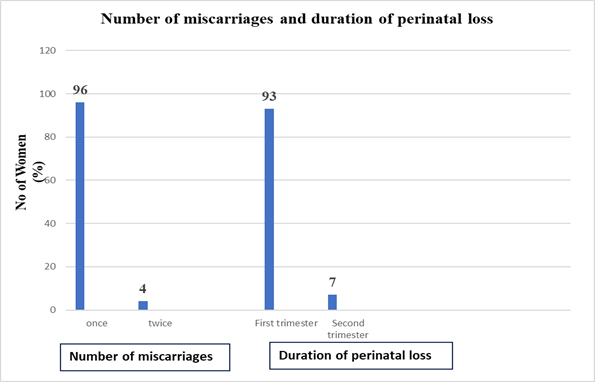

Number of miscarriages and duration of perinatal loss in studied women is given in Table 5 and Graph 5.

Table 5: Number of miscarriages and duration of perinatal loss in studied women.

| S.no | Parameters | No of Women (%) (n=100) | |

| 1 | Number of miscarriages | Once | 96 |

| Twice | 4 | ||

| 2 | Duration of perinatal loss | First trimester (Conception to 12 weeks) | 93 |

| Second trimester (till 20 weeks) | 7 |

Graph 5: Number of miscarriages and duration of perinatal loss in studied women

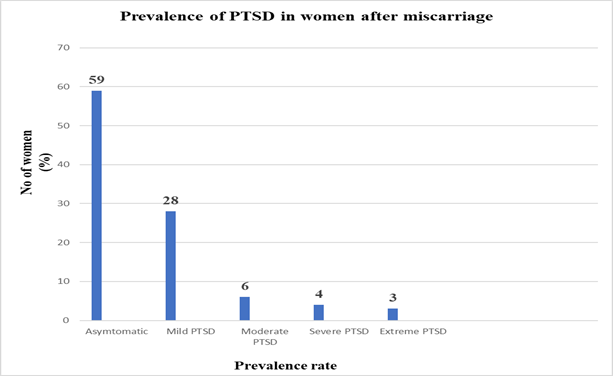

Prevalence of PTSD in women after miscarriage were given in Table 6 and Graph 6.

Table 6: Prevalence of PTSD in women after miscarriage

| Prevalence | n=100 (%) |

| Asymptomatic (0-10) | 59 |

| Mild PTSD (11 – 22) | 28 |

| Moderate PTSD (23 – 34) | 6 |

| Severe PTSD (35 – 46) | 4 |

| Extreme PTSD (≥ 47) | 3 |

Graph 6: Prevalence of PTSD in women after miscarriage.

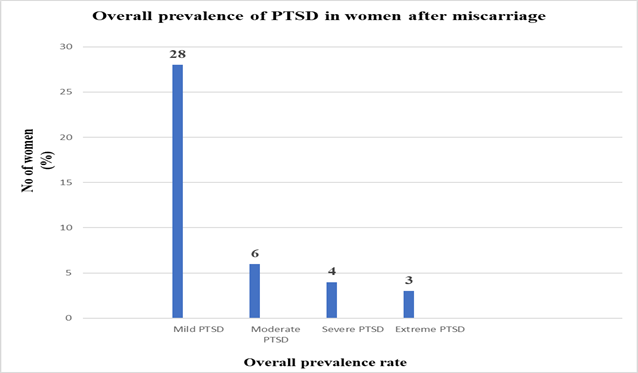

Overall prevalence of PTSD in women after miscarriage were given in Table 7 and Graph 7.

Table 7: Overall prevalence of PTSD in women after miscarriage

| Overall Prevalence | n=100 (%) |

| Mild PTSD (11 – 22) | 28 |

| Moderate PTSD (23 – 34) | 6 |

| Severe PTSD (35 – 46) | 4 |

| Extreme PTSD (≥ 47) | 3 |

| Total | 41 |

Graph 7: Overall prevalence of PTSD in women after miscarriage

Discussion

In this work, we evaluated the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in married women after a miscarriage or perinatal loss as depicted in Graph/Table 7 that the overall prevalence percentage of PTSD in women who had experienced miscarriage within the time period of six months is considerably moderate i.e. 41% (sample size=100). Pregnancy loss (miscarriage) have been established as traumatic events that can lead to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder [20]. Even if such women who had previously suffered from miscarriage associated symptoms of PTSD became pregnant again are at higher risk for several obstetric complications including ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, hyperemesis and preterm contractions [21]. Posttraumatic stress is a consequence of and reaction to an extremely stressful event miscarriage in our research study causing trauma. This event exceeds the coping capacity of the person who was a participant and/or witness causing non-adaptive forms of functioning [22]. It is characterized by symptoms of reliving as depicted in Graph/Table 1 that the women who had suffered from miscarriage within the time period of six months 52% experiences intrusive memories or thoughts, 41% had nightmares regarding the incident and 76% had flashbacks of that painful event. In addition,64% of these women exhibited avoidance cues/thoughts related to trauma,39% were in a state of emotional numbness and 51% indicated signs of limited affect and social isolation as depicted in Graph/Table 2. The possible reason for such behaviour is that the experience of miscarriage as a trauma is perceived when the relationship with the unborn child has developed. Studies have shown that regardless of the duration of pregnancy, it is professed as the embodiment of hope for parenthood, and even an early pregnancy is treated as a biological child [23]. Symptoms of increased arousal is very common in women who had recently suffered from miscarriage as depicted by our obtained results in Graph/Table 3, increased agitation (irritability), disrupted sleep cycle, excessive vigilance and concentration problems are quite prominent in these women effecting their quality of life. Assessment of PTSD in women who had experienced miscarriage is critical given the growing literature regarding the adverse effects of psychological distress and mental illness on maternal well-being [24]. In response to this event, many women experience a number of negative reactions such as sadness, anger, disappointment, crying(mourn) and guilt. All these emotions may persist for a very long time and intensify in certain situations, such as the sight of a family with a child, family meetings, the anniversary of a child’s death, or the day of the expected birth [25]. Our study has shown that the symptoms of mourning after a miscarriage are very common and occur in as much as 90% of women due to childlessness, lack of social support and earlier pregnancy loss followed by 79% of feeling of guilt (especially when there is no medical explanation for loss), as depicted in Graph/Table 4. Over time, these reactions reduce their intensity and most women accept the loss. However, some of them may indicate the occurrence of complicated mourning and may develop depressive reactions, anxiety disorders, even suicidal thoughts [26]. Our results revealed that 45% women developed anxiety and 58% were depressed after the incident of miscarriage (Graph/Table 4). The conception can also be a factor in the occurrence of depression after miscarriage [27]. It has been shown that women who had difficulties in this area are more likely to develop depression after this event. This is probably due to the fear of whether they will be able to get pregnant again [28]. Thus, the abovementioned data confirm that depression or anxiety disorders after miscarriage are indeed a significant clinical problem in women who had suffered from miscarriage. Miscarriage not only have a significant impact on the quality of life of the affected women but also have a negative impact on her sexual partner. it seems that the father of the child experiences loss in a similar way and it is equally painful for him. Usually, however, he does not allow himself to experience sadness because he wants to be supportive to the woman or for fear that it will be against accepted cultural norms [29]. The severity of PTSD symptoms in women who had suffered from miscarriage is also associated with the duration and number of miscarriages as well. Our study revealed that a high percentage of women had suffered from miscarriage during first trimester i.e. 93% and a very low proportion of women reported pregnancy loss in the second trimester i.e.7% (Graph/Table 5). And 96% of women reported perinatal loss once within the time period of six months while only 4% of women had experienced perinatal loss twice in the last six months (Graph/Table 5). Our results are in accordance with the medical citations since the higher possibility for miscarriages are documented in the first trimester in pregnant women and the likelihood to become pregnant again is possible but low subsequently it depends on numerous factors such as women mental/physical health, doctor guidelines regarding physical recovery from miscarriage complications etc [30,31]. However it is reported that the women who had suffered miscarriage twice had higher results of depression and anxiety intensity than the women who miscarried once resulting from mild to moderate PTSD and even to severe as a consequence (Graph/Table 6).Other triggering factors may include personality factors (neuroticism), sociodemographic factors (low education, non-supportive partner/in-laws, society pressure etc),age, previous losses (regardless of maternal status), childlessness and fertility problems. Thus, efforts should have been made to raise awareness of the distinction between PTSD and other complications, such as depression or mourning after the loss of a child (miscarriage) [32]. Understanding such strong responses to stress is important because skillful prevention can make a significant difference to the experience of subsequent pregnancies, particularly in terms of reducing the level of anxiety for fear of subsequent loss [33]. However, it is important that medical personnel try to understand not only the medical aspect of this fact, but also the related experiences and emotions of women. Supporting women after a miscarriage can also help build a constructive relationship with the children born after the loss, so that unresolved grief and depression do not affect their formation in a negative way [34]. Proper communication and reliable and empathetic feedback from health professionals also seem important.

Conclusion

Untreated posttraumatic stress disorder has a significant impact on the quality of life, social relations, ability to work, risk of suicide, psychophysical health, or future pregnancies. The risk of posttraumatic stress disorder among women after miscarriage is often neglected in medical or health science studies, and the available literature broadly describes mostly the issues of post-loss rights, psychological factors associated with loss, or complicated grief. Yet untreated and unrecognized psychological complications after miscarriage may not only worsen women’s emotional functioning, but also affect their overall quality of life by weakening their health or depriving them of social contact.

References

- Amezcua, M., & Gálvez Toro, A. (2002). Modes of analysis in qualitative health research: critical perspective and reflections aloud. Spanish Journal of Public Health, 76:423-436.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beck, C. T., & Barnes, D. L. (2006). Post-traumatic stress disorder in pregnancy. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 9(2):4-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Białek, K., & Malmur, M. (2020). Risk of post-traumatic stress disorder in women after miscarriage. Medical Studies/Studia Medyczne, 36(2):134-141.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Białek, K., & Malmur, M. (2020). Risk of post-traumatic stress disorder in women after miscarriage. Medical Studies/Studia Medyczne, 36(2):134-141.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Brewin, C. R. (2007). What is it that a neurobiological model of PTSD must explain? Progress in Brain Research, 167:217-228.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Broen, A. N., Moum, T., Bødtker, A. S., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2005). The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: a longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC medicine, 3:1-14.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cohain, J. S., Buxbaum, R. E., & Mankuta, D. (2017). Spontaneous first trimester miscarriage rates per woman among parous women with 1 or more pregnancies of 24 weeks or more. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17:1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cook, C. A. L., Flick, L. H., Homan, S. M., Campbell, C., McSweeney, M., & Gallagher, M. E. (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103(4):710-717.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cummings, G. E., & Mayes, D. C. (2007). A comparative study of designated Trauma Team Leaders on trauma patient survival and emergency department length-of-stay. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 9(2):105-110.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Daugirdaitė, V., van den Akker, O., & Purewal, S. (2015). Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder after termination of pregnancy and reproductive loss: a systematic review. Journal of pregnancy.

Publisher | Google Scholor - De Boer, J. C., Lok, A., van’t Verlaat, E., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Bakker, A. B., & Smit, B. J. (2011). Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analysis. Social science & medicine, 73(2):316-326.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Díaz-Pérez, E., Haro, G., & Echeverria, I. (2023). Psychopathology Present in Women after Miscarriage or Perinatal Loss: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International, 4(2):126-135.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dowlati, Y., Herrmann, N., Swardfager, W., Liu, H., Sham, L., Reim, E. K., & Lanctôt, K. L. (2010). A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biological psychiatry, 67(5):446-457.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dyregrov, A. (1990). Parental reactions to the loss of an infant child: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 31(4):266-280.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Engelhard, I. M., van den Hout, M. A., & Arntz, A. (2001). Posttraumatic stress disorder after pregnancy loss. General hospital psychiatry, 23(2), 62-66.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Farren, J., Jalmbrant, M., Ameye, L., Joash, K., Mitchell-Jones, N., Tapp, S., ... & Bourne, T. (2016). Post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ open, 6(11):e011864.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Farren, J., Jalmbrant, M., Falconieri, N., Mitchell-Jones, N., Bobdiwala, S., Al-Memar, M., ... & Bourne, T. (2020). Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology:222(4):367.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Geller, P. A., Klier, C. M., & Neugebauer, R. (2001). Anxiety disorders following miscarriage. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(6):432-438.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hardy, K., & Hardy, P. J. (2015). 1st trimester miscarriage: four decades of study. Translational pediatrics, 4(2):189.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Janssen, A. L., MacLeod, R. D., & Walker, S. T. (2008). Recognition, reflection, and role models: Critical elements in education about care in medicine. Palliative & Supportive Care, 6(4):389-395.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Johnson, M. P., & Baker, S. R. (2004). Implications of coping repertoire as predictors of men's stress, anxiety and depression following pregnancy, childbirth and miscarriage: a longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 25(2):87-98.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Klier, C. M., Geller, P. A., & Ritsher, J. B. (2002). Affective disorders in the aftermath of miscarriage: a comprehensive review. Archives of women's mental health, 5:129-149.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Krosch, D. J., & Shakespeare-Finch, J. (2017). Grief, traumatic stress, and posttraumatic growth in women who have experienced pregnancy loss. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(4):425.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kulathilaka, S., Hanwella, R., & de Silva, V. A. (2016). Depressive disorder and grief following spontaneous abortion. BMC psychiatry, 16:1-6.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lee, E., Faber, J., & Bowles, K. (2022). A review of trauma specific treatments (tsts) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Clinical Social Work Journal, 1-13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lee, H. J., Lee, M. S., Kang, R. H., Kim, H., Kim, S. D., Kee, B. S., ... & Paik, I. H. (2005). Influence of the serotonin transporter promoter gene polymorphism on susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and anxiety, 21(3):135-139.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lewkowitz, A. K., Gupta, A., Simon, L., Sabol, B. A., Stoll, C., Cooke, E., ... & Tuuli, M. G. (2019). Intravenous compared with oral iron for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Perinatology, 39(4):519-532.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Maconochie, N., Doyle, P., Prior, S., & Simmons, R. (2007). Risk factors for first trimester miscarriage—results from a UK‐population‐based case–control study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 114(2):170-186.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Maker, C., & Ogden, J. (2003). The miscarriage experience: more than just a trigger to psychological morbidity? Psychology and health, 18(3):403-415.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Murlikiewicz, M. A. G. D. A. L. E. N. A., & Sieroszewski, P. I. O. T. R. (2012). Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following miscarriage. Archives of Perinatal Medicine, 18(3):157-162.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Prettyman, T. H., Gardner, R., Russ, J. C., & Verghese, K. (1993). A combined transmission and scattering tomographic approach to composition and density imaging. Applied radiation and isotopes, 44(10-11):1327-1341

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shakeel, G., Shafi, I., Noor, R., & Bashir, S. (2021). Prevalence of stress among women after first trimester miscarriage. Rawal Medical Journal, 46(2):391.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Skogrand, L., DeFrain, J., DeFrain, N., & Jones, J. (2012). Surviving and transcending a traumatic childhood: The dark thread. Routledge.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Söderquist, J., Wijma, K., & Wijma, B. (2004). Traumatic stress in late pregnancy. Journal of anxiety disorders, 18(2):127-142.

Publisher | Google Scholor