Research Article

Prevalence And Associated Factors of Anemia Among Reproductive Women in Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study

- Gebru Gebremeskel Gebrerufael *

- Bsrat Tesfay Hagos

Department of Statistics, College of Natural and Computational Science, Adigrat University, Adigrat, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Gebru Gebremeskel Gebrerufael, Department of Statistics, College of Natural and Computational Science, Adigrat University, Adigrat, Ethiopia.

Citation: Gebru G. Gebrerufael, Bsrat T. Hagos. (2023). Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anemia Among Reproductive Women in Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of BioMed Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 2(4):1-10. DOI: 10.59657/2837-4681.brs.23.031

Copyright: © 2023 Gebru Gebremeskel Gebrerufael, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: July 20, 2023 | Accepted: August 04, 2023 | Published: August 11, 2023

Abstract

Background: Anemia for women in reproductive age continues to be a serious public health issue, especially in countries in Africa like Ethiopia. It is the most frequent reason for serious effects for both the mother and the fetus in women. There have been few investigations on the prevalence and determinants of anemia among reproductive women in the Somali regional state of Eastern Ethiopia. Because of this, the purpose of this study was to identify the prevalence and risk factors for anemia in the Somali regional state.

Methods: From January 18 to June 27, 2016, a community-based cross-sectional investigation was carried out. STATA version 12 was used for the statistical analysis. We performed descriptive and summary statistics. To identify the significant factors connected to anemia, a multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was carried out after verifying for assumptions. In the multivariable model, risk factors for anemia were identified as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value < 0.05.

Results: In this study, the overall prevalence of anemia among reproductive women residing in the Somali regional state was 58.4% (95% CI (0.557–0.611)). Around 8.7%, 40.03% and 51.29% of which anemic level reproductive women (15-49 years) were with severe (hemoglobin level: < 7.0 g per dl), moderate (hemoglobin level: 7.0–9.9 g per dl) and mild (hemoglobin level: 10–10.9 g per dl) type respectively.

The multivariable binary logistic analysis revealed, predictors of rural residence (AOR =1.4; 95% CI: (1.08–1.93)), giving birth at older age of maternal 20–29 (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI: (1.19–2.54)), 30–39 (AOR =1.9; 95% CI: (1.27–2.76)), and 40–49 (AOR =1.8; 95% CI: (1.08–2.97)) years, being having antenatal care (ANC) follow-up (AOR = 0.44; 95% CI: (0.224–0.868)), and home place of delivery (AOR =1.5; 95% CI: (1.04–2.21)) were statistically predictors associated with anemia.

Conclusions: In general, it is still discovered that the prevalence of anemia among reproductive women in the research area is extremely high (far above the national average). Rural residence, home place of delivery, ANC follow-up, and giving birth at older age of maternal were investigated as significant associated predictors of anemia among the study participants. Therefore, filling in the gaps that were discovered should lessen the anemia that is now an issue for women in this study who are of reproductive age.

Keywords: anemia, somali; predictors; reproductive women; logistic regression

Introduction

Anemia is commonly understood to be a decrease in hemoglobin level concentration, hematocrit, or the number of red blood cells per litter below the reference interval for healthy individuals of similar sex, age, race, altitude, smoking status, and pregnancy status under similar environmental circumstances [1, 2]. It displays both inadequate dietary intake and poor health. The definitions of anemia disease vary according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. It is categorized as follows: for children under the age of five, the threshold hemoglobin level for being anemic is hemoglobin level: < 11>

Although it can affect anyone at any time and at any stage of life, it is more common in women of reproductive age, including both pregnant and non-pregnant women [4-6, 8, 9]. It causes premature birth [10], underweight birth [11], fetal cognitive impairment [12, 13], and fetal mortality [12, 13] and is the most common risk factor for death and illness among reproductive-aged women in low-income countries. Although the Ethiopian government and its shareholders have done their utmost to reduce anemia prevalence in the nation, anemia is still a serious public health issue among Ethiopian women of reproductive age. The 2016 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) report states that anemia in women of reproductive age continues to be catastrophic in Ethiopia (the prevalence is reported to be 24%). Additionally, the prevalence rates vary by geographical regional state. The Somali national regional state reported the highest percentage in Ethiopia, which was calculated to be at 59.5% [8, 14]. Studies done in the past in Ethiopia have a national focus [15, 16]. Such studies overlook a crucial consideration for those who build and plan policies since the results at the national level may not accurately reflect the situation at the regional state levels. To my knowledge, no regional research has been done on the causes of anemia in the Somali regional state. To fill in these gaps, the authors conducted a thorough community-based cross-sectional study design of the most recent 2016 EDHS survey in order to investigate the most significant risk factors for anemia in the Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia, while taking into account a variety of environmental and sociodemographic predictors [8, 14].

Objective of the study

General objective

The general aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and predictors associated with anemia in the Somali regional state, eastern Ethiopia using the 2016 EDHS data set.

Specific objectives

- To assess the prevalence rate of anemia among reproductive women.

- To identify the socio-demographic and environmental predictors associated with anemia.

Methods and Materials

Source of data, study design, and period

On the basis of data from the 2016 EDHS, this study was based on secondary analysis of a community-based retrospective cross-sectional survey design that was carried out in the Somali regional state from January 18, 2016, to June 27, 2016. This fourth current survey report was conducted by the Ethiopian Ministry of Health (EMOH), Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EHI), and Ethiopian Central Statistics Agency Office (ECSAO). These records were obtained with permission from the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) measure program [8].

Study area

There were reportedly four million people living there. In the Somali regional state, there are three different ways of life: urban, pastoral, and agro-pastoral [17]. The majority (85%) of the projected regional population depends on pastoralism and agro-pastoralism for their livelihood. There are nine zones in the Somali regional state. With a land area of 375,000 km2, the Somali regional state is the second largest of Ethiopia's nine regional states. Sample size and sampling technique, study population, and data collection

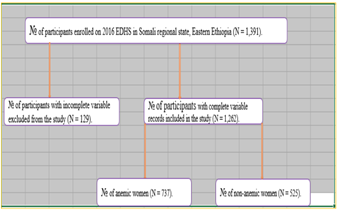

The study covered all women between the ages of 15-49 who were fertile. Women who met the eligibility requirements were interviewed face-to-face for the data collection. According to the 2016 EDHS data, the Somali regional state has Ethiopia's highest prevalence rates of anemia among reproductive women. In the five years before to the census, 1,391 reproductive women in this regional state were recorded. Following that, the entire EDHS 2016 survey report showed reproductive-aged women with detailed information and sampling selection technique on anemia status within the preceding five years [8]. Finally, the study comprised samples totaling 1,262 reproductive women who provided complete dataset on all of the factors taken into account (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the sampling procedure of anemic women in the Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia.

Study variables

The dependent variable in this study was the anemia status of reproductive women, which is a dichotomous variable coded as “0” if the women is non-anemic and “1” if the women is anemic. Such that

The predictor variables included in the study were presented on Table 1 with its detailed definition and categorization. The degree for severity of anemia in pregnant women was determined based on hemoglobin concentration in blood adjusted to altitude. This adjusted concentration classified into three as per WHO criteria [3, 18, 19]:

Mild anemia (i.e., hemoglobin level: 10–10.9 g per dl)

Moderate anemia (i.e., hemoglobin level: 7–9.9 g per dl)

Severe anemia (i.e., hemoglobin level: less than 7 g per dl).

Table 1: Statistical data processing and analysis Table 1 Operational definitions and categorizations of predictor variables.

| Variables | Categorizations of predictor variables |

| Maternal age | Maternal age of participants (in year) (15–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49) |

| Residence | Residence place of women (urban, rural) |

| Education level | Education level of participants (no education, primary, secondary, tertiary) |

| Current history of malaria | Current history of malaria of participants (no, yes) |

| Birth type | Birth type of participants (multiple, singleton) |

| Type of toilet facility | Type of toilet facility of participants (yes, no) |

| Sex of child | Sex of children born (female, male) |

| ANC follow up | Antenatal care follows up of women (no, yes) |

| Place of delivery | Place of delivery of participants (heath facility, home) |

| Presence of current blood loss | Presence of current blood loss of reproductive women (yes, no) |

| First pregnancy iron supplements | First pregnancy iron supplements of participants (no, yes) |

| Smokes cigarettes | Smokes cigarettes of reproductive participants (no, yes) |

| Current breastfeeding | Current breastfeeding of participants (yes, no) |

| Occupation | Occupation of reproductive women (no, yes) |

| Sex of household | Sex of household of participants (male, female) |

Using STATA version 12, the obtained data were cleaned, coded, input, and tested for accuracy. We performed descriptive and summary statistics. Analysis of binary logistic regression models with bivariable and multivariable contributions was used to determine the strength of the correlation between the response variable and the predictor variables.

The loglikelihood ratio test, Hosmer, and Lemeshow model tests all used the goodness-off fit test of model analysis.

Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used to evaluate the validity of the multicollinearity assumption on predictor variables. It was determined that significant risk factors for anemia in the multivariable model were adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The cross-sectional study comprised 1,262 women in the reproductive age group, of which 737 (58.4%) were anemic. From the total of participants, 963 (76.3%) of them lived in rural areas and 1222 (96.8%) did not follow ANC service during pregnancy. The majority of participants 1105 (87.6%) of them were born to their children in a health facility place of delivery. From all, 641 (50.8%) of them were currently breastfeeding. On the subject of education, 950 (75.3%) of them were uneducated, 222 (17.6%) of them were complete primary education complete, and 64 (5.07%) were secondary education level (Table 2).

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of reproductive-aged women in the Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia, January 18, 2016 to June 27, 2016 (N=1,262).

| Variables | Categories | VIF |

| Maternal age | 15–19 (ref.) | |

| 20–29 | 3.26 | |

| 30–39 | 2.45 | |

| 40–49 | 4.05 | |

| Residence | Urban (ref.) | |

| Rural | 4.52 | |

| Education level | No education (ref.) | |

| Primary | 1.75 | |

| Secondary | 1.33 | |

| Tertiary | 1.27 | |

| Current history of malaria | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 7.41 | |

| Birth type | Multiple (ref.) | |

| Singleton | 4.41 | |

| Type of toilet facility | Yes (ref.) | |

| No | 1.86 | |

| Sex of child | Female (ref.) | |

| Male | 1.12 | |

| ANC follow up | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.1 | |

| Place of delivery | Health facility (ref.) | |

| Home | 1.21 | |

| Presence of current blood loss | Yes (ref.) | |

| No | 3.24 | |

| First pregnancy iron supplements | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 5.44 | |

| Smokes cigarettes | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.04 | |

| Current breastfeeding | Yes (ref.) | |

| No | 4.18 | |

| Occupation | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.39 | |

| Sex of household | Male (ref.) | |

| Female | 1.53 | |

| Mean VIF | 2.77 |

Prevalence of anemia among reproductive women

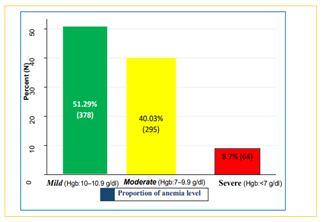

In the current study, 1,262 reproductive women's overall anemia prevalence rate was discovered to be 58.4% with 95% CI (0.557–0.611) (see Table 2). Of the anemic reproductive women, 378 (51.29%) had mild anemia (10.0–10.9 g/dl), 295 (40.3%) had moderate anemia (7.0–9.9 g/dl), and 64 (8.7%) had severe anemia (less than 7.0 g/dl) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Shows the prevalence degree of anemia among reproductive women in the Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia (January 18, 2016 to June 27, 2016).

The degree of multicollinearity assumptions of the binary logistic regression model was tested on each predictor individually and on average using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value < 10 xss=removed xss=removed src="https://bioresscientia.com/uploads/articles/1692884432image1.png"> value = 2.6 and P-value = 0.956) (Table 4).

Table 3: Test the degree of multi-collinearity of a logistic regression model.

| Variables | Categories | VIF |

| Maternal age | 15–19 (ref.) | |

| 20–29 | 3.26 | |

| 30–39 | 2.45 | |

| 40–49 | 4.05 | |

| Residence | Urban (ref.) | |

| Rural | 4.52 | |

| Education level | No education (ref.) | |

| Primary | 1.75 | |

| Secondary | 1.33 | |

| Tertiary | 1.27 | |

| Current history of malaria | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 7.41 | |

| Birth type | Multiple (ref.) | |

| Singleton | 4.41 | |

| Type of toilet facility | Yes (ref.) | |

| No | 1.86 | |

| Sex of child | Female (ref.) | |

| Male | 1.12 | |

| ANC follow up | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.1 | |

| Place of delivery | Health facility (ref.) | |

| Home | 1.21 | |

| Presence of current blood loss | Yes (ref.) | |

| No | 3.24 | |

| First pregnancy iron supplements | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 5.44 | |

| Smokes cigarettes | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.04 | |

| Current breastfeeding | Yes (ref.) | |

| No | 4.18 | |

| Occupation | No (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.39 | |

| Sex of household | Male (ref.) | |

| Female | 1.53 | |

| Mean VIF | 2.77 |

Predictors associated with anemia among reproductive women

The multivariable binary logistic regression model analysis of major determinant risk predictors associated with anemia disease was revealed in Table 4. This result presented residence, place of delivery, maternal age, and ANC follow up of mothers were found to be statistically significant predictors associated with anemia.

The probability of being anemic increased with increased age. Women with age of 20–29, 30–39, and 40–49 years had 1.7, 1.9, and 1.8-times higher odds of being anemic compared to those aged 15–19 years respectively (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI: (1.19–2.54)), (AOR =1.9; 95% CI: (1.27–2.76)), and (AOR =1.8; 95% CI: (1.08–2.97)).

Concerning ANC follow up, having ANC follow up of women during pregnancy were less likely to be anemic keeping all other variables constant. The odds of being anemic were 56% times lower among reproductive women with ANC follow up than the counterpart (AOR = 0.44; 95% CI: (0.224–0.868)).

In women of reproductive age, the place of delivery was discovered to be a statistically significant prognostic factor of anemia infection. When we related to reproductive mothers who were born at home, those mothers who were born in a health facility had significantly higher odds of anemia (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI: (1.04–2.21)). Finally, it was discovered that the place of residence was also substantially related to anemia infection. The odds of being anemic were around 1.4 times higher among women who live in rural areas than its counterpart (AOR = 1.4; 95%CI: (1.08–1.93)).

Table 4: Bi-variable and multivariable analysis using the logistic regression model for predictor of anemia among reproductive women in the Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia (January 18, 2016 to June 27, 2016).

| Bi-variable result | Multivariable results | ||

| Variables Maternal age | Categories | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| 15–19 (ref.) | |||

| 20–29 | 1.8(1.26, 2.46) * | 1.7(1.19, 2.54) * | |

| 30–39 | 2.1(1.45, 2.96) * | 1.9(1.27, 2.76) * | |

| 40–49 | 1.2(0.804, 1.65) | 1.8(1.08, 2.97) * | |

| Residence | Urban (ref.) | ||

| Rural | 1.8(1.35, 2.28) * | 1.4(1.08, 1.93) * | |

| Education level | No education (ref.) | ||

| Primary | 0.64(0.480, 0.864) * | 0.84(0.569, 1.23) | |

| Secondary | 0.48(0.289, 0.805) * | 0.74(0.409, 1.35) | |

| Tertiary | 0.39(0.174, 0.865) * | 0.69(0.272, 1.75) | |

| Current history of malaria | No (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.9(1.37, 2.60) * | 1.2(0.806, 1.86) | |

| Birth type | Multiple (ref.) | ||

| Singleton | 0.57(0.445, 0.732) * | 0.76(0.482, 1.20) | |

| Type of toilet facility | Yes (ref.) | ||

| No | 1.3(1.06, 1.69) * | 1.1(0.844, 1.46) | |

| Sex of child | Female (ref.) | ||

| Male | 0.82(0.534, 1.25) | 0.74(0.479, 1.14) | |

| ANC follow up | No (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 0.46(0.244, 0.881) * | 0.44(0.224, 0.868) * | |

| Place of delivery | Health facility (ref.) | ||

| Home | 1.5(1.062, 2.15) * | 1.5(1.04, 2.21) * | |

| Presence of current blood loss | Yes (ref.) | ||

| No | 1.8(1.45, 2.33) * | 1.3(0.860, 1.81) | |

| First pregnancy iron supplements | No (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 0.60(0.476, 0.755) * | 1.2(0.808, 1.74) | |

| Smokes cigarettes | No (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 0.24(0.025, 2.28) | 0.52(0.062, 4.43) | |

| Current breastfeeding | Yes (ref.) | ||

| No | 0.51(0.403, 0.636) * | 0.73(0.519, 1.036) | |

| Occupation | No (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 0.72(0.547, 0.953) * | 0.84(0.619, 1.14) | |

| Sex of household | Male (ref.) | ||

| Female | 1.0(0.793, 1.29) | 0.59(0.298, 1.18) | |

| Note: LRT [X^2 (DF = 19)] = 82.3 and p-value = 0.000, Hosmer-Lemeshow Test [X^2 (DF = 8)] = 2.6 and p-value = 0.956, ref.: reference, *significance at p-value less than 0.05, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio | |||

Discussion

This study looked into the prevalence and risk factors for anemia, a significant public health issue, among reproductive women in the Somali regional state of eastern Ethiopia. Overall, the current study's anemic prevalence was 58.4% with 95% CI (0.557–0.611). This study was in line with previous studies conducted in India, 62.4% [20], Central and West Africa, 56% and South Asia, 52% [6]. However, it was noted that our results were higher than those of similar earlier studies in Debre Berhan, 9.70% [21], Sudan, 10.0% [22], Addis Ababa, 11.60% [23], Iran, 13.60% [24] and southern Ethiopia, 27.6%% [1] and lower than other studies conducted in Jhalawar, Rajasthan, 81.8% [25], Pune, India, 81% [26] and Katihar Medical College & Hospital, Bihar, 88.5% [27].

Geographical differences, differences in sociodemographic status, dietary habits of study participants, and the inclusion of reproductive women who take iron-folate supplements in the paper could all be contributing factors to the gap [23]. Additionally, the higher prevalence of parasitic illnesses like malaria and hookworm in the study area may be a factor in the higher prevalence of anemia sickness there. In this investigation, the most of anemic respondent cases, 51.29% (378/737) were mild, followed by 40.03% (295/737) moderate cases of anemia infection. A similar distribution of anemia disease was stated in Ethiopia and Kenya (62.50% & 37.50%) [3, 28] & Nepal (67.10% & 28.60%) [29] in which most of the respondent cases was mild anemia disease followed by moderate anemia disease respectively. However, in contrast to this investigation, studies done in Kenya (70.70% & 26.30%) [30] and southern Ethiopia (60.0% & 34.30%) [31] most of the anemic respondent cases were moderate followed by mild similarly.

Among the Somali regional state, it was discovered that place of residence was a significant predictor of anemia among women of reproductive age. It was discovered that anemic women were less likely to reside in urban areas than in rural ones. This investigation agreed with studies carried out in several regions of Ethiopia [15, 14, 32]. This discrepancy may be caused by the higher household income, better antenatal care services, and better access to mass media for health service usages among women who live in metropolitan regions. Maternal age was discovered to be a major predictor of anemia in women in the Somali regional state in this study. This result is consistent with the study conducted in Uganda and Ethiopia [7, 15]. The reason could be that women in reproductive age groups give birth to more children overall. Similar to this, women who underwent ANC follow-up during pregnancy had a decreased risk of anemia than women who did not. This result is in line with the results of the Ethiopian study [1]. This may be due to the fact that mothers who make adequate use of maternal health services, such as ANC follow-up, may receive the right information about their own health and adopt the right feeding habits to ward off diseases like malaria. Finally, the home place of delivery for reproductive women was a possible risk factor for anemia (AOR =1.5; 95% CI: (1.04-2.21)). This investigation was in line with studies carried out in several regions of Ethiopia [8, 33]. This variation may be the result of efficient management and utilization of preventive plans in hard work controlling as the mothers are cared for by a health expert professional.

Conclusion

This study showed that, compared to the national average, the prevalence of anemia among reproductive women in the Somali regional state was remained relatively high. Rural residence, home place of delivery, ANC follow-up, and giving birth at older age of maternal were investigated as significant associated predictors of anemia among the study participants. Therefore, filling in the gaps that were discovered should lessen the anemia that is now an issue for women in this study who are of reproductive age.

Limitations of the study

The anemia issue in the study area was detected by this investigation. However, some of the restrictions need to be considered. Due to the secondary nature of the data used in this study, significant predictor variables such hookworm infection, gestational age, and nutritional information would be overlooked. The study was conducted six years ago, therefore it is unlikely to reflect the most recent anemia statistics in the area.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since the study was a secondary data analysis of publicly available survey data from the MEASURE DHS program, ethical approval and participant consent were not necessary. We requested DHS Program and permission was granted to download and use the data from http://www.dhsprogram.com. There are no names of individuals or household addresses in the data files.

Availability of data and materials: The data set is available online and any one can access it from www.measuredhs.com.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

GGG conceived and designed the study. GGG wrote the background section reviewed literature. GGG and BTH analyzed the data, interpreted the results and participated in the drafting of the manuscript. Both authors read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Getahun W, Belachew T, Wolide AD. (2017). Burden and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care in southern Ethiopia: cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gebreweld A, Ali N, Ali R, Fisha T. (2019). Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among children under five years of age attending at Guguftu health center, South Wollo, Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 14(7):e0218961.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Berhe B, Mardu F, Legese H, Gebrewahd A, Gebremariam G, Tesfay K, Kahsu G. et al. (2019). Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Adigrat General Hospital, Tigrai, northern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes, 12:310.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Afeworki R, Smits J, Tolboom J, van der Ven A (2015). Positive Effect of Large Birth Intervals on Early Childhood Hemoglobin Levels in Africa Is Limited to Girls: Cross-Sectional DHS Study. PLoS ONE, 10(6):e0131897.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bekele A, Tilahun M, and Mekuria A. (2016). Prevalence of Anemia and Its Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care in Health Institutions of Arba Minch Town, Gamo Gofa Zone, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study, 2016:9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, et al. (2013). Global, regional, and national trends in hemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995-2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health, 1: e16-e25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nankinga O and Aguta D. (2019). Determinants of Anemia among women in Uganda: further analysis of the Uganda demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health, 19:1757.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. (2016). Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alemayehu M, Meskele M, Alemayehu B, Yakob B (2019). Prevalence and correlates of anemia among children aged 6-23 months in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 14(3):e0206268.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Levy A, Fraser D, Katz M, Mazor M, Sheiner E. (2005). Maternal anemia during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for low birth weight and preterm delivery. Eur J Obstetrics Gynecol Reprod Biol, 122(2):182-186.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Banhidy F, Acs N, Puho EH, Czeizel AE. (2011). Iron deficiency anemia: pregnancy outcomes with or without iron supplementation. Nutrition, (1):65-72.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kalaivani K. Prevalence & consequences of anemia in pregnancy. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130(5):627-633.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Walter T. (2003). Efect of iron-deficiency anemia on cognitive skills and neuromaturation in infancy and childhood. Food Nutr Bul, 24(4):104-110.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kibret KT, Chojenta C, D’Arcy E, et al. (2019). Spatial distribution and determinant factors of anaemia among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia: a multilevel and spatial analysis. BMJ Open, 9:e027276.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Argawu AS, Mekebo GG, Bedane K, Makarla RK, Kefale B. et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Anemia among Reproductive-aged Women in Ethiopia: A Nationally Representative Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International. 33(59B):687-698.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gebremedhin S and Enquselassie F. (2011). Correlates of anemia among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia: Evidence from Ethiopian DHS 2005. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 25(1):22-30.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Devereux S: (2006). Vulnerable Livelihoods in Somali Region, Ethiopia.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Benoist B, McLean E, Egli I, Cogswell M. (2008). World Health Organization, centers for disease control and prevention: worldwide prevalence of anemia 1993–2005. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muchie KF. (2016). Determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: further analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Nutrition, 2:51.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Siddalingappa H, Murthy NMR, Ashok NC. (2016). Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among pregnant women in rural Mysore, Karnataka, India. Int J Community Med Public Health, 3:2532-2537.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Abere Y. (2014). Pregnancy anemia prevalence and associated factors among women attending ante natal care in North Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. RSSDIJ., 3:3.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Abdelgader EA, Diab TA, Kordofani AA, Abdalla SA. (2014). Hemoglobin level, RBCs Indices, and iron status in pregnant females in Sudan. Basic Res J Med Clin Sci. 3(2):8-13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gebreweld A, Tsegay A. (2018). Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Adv Hematol.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Barooti M, Rezazadehkermani B, Sadeghirad S, Motaghipisheh S, Arabi M. (2010). Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among Iranian pregnant women; a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Reprod Fertil, 11(1):17-24.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumar V, Jain M, Shukla U, Swarnkar M, Gupta P, Saini P. (2019). Prevalence of Anemia and Its determinants among Pregnant Women in a Rural Community of Jhalawar, Rajasthan. Natl J Community Med, 10(4):207-211.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kundap RP, Dadewar A, Singru S, Fernandez K. (2016). A Comparative Study of Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Antenatal Women from Urban and Rural Area of Pune, India. Ntl J Community Med, 7(5):351-354.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumari S, Bharati DR, Jayaswal AK, Pal R, Sinha S, Kumari A. (2017). Prevalence of Anemia and Associated Risk Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Clinic at Katihar Medical College & Hospital, Bihar. Natl J Community Med, 8(10):583-587.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Siteti M, Namasaka SD, Ariya OP, Injete SD, Wanyonyi WA. (2014). Anemia in pregnancy: prevalence and possible risk factors in Kakamega County, Kenya. SJPH, 2(3):216-222.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh P, Khan S, Mittal RK. Anemia during pregnancy in the women of western Nepal. BMJ. 2013;2(1):14-16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tekeste O. (2015). Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in the second and third trimesters at Pumwani maternity Hospital, Nairobi.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gedefaw L, Ayele A, Asres Y, Mossie A. (2015). Anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in Wolayita Sodo Town, southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci, 25:2.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Özaltin E, et al. (2011). Anemia in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 378:2123-2135.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Maawiya, Rukiya A. (2011). Burden and determinants of post-partum anemia in mariakani sub-county hospital, Nairobi.

Publisher | Google Scholor