Case Report

Posterior only for Approach Total EN Bloc Spondylectomy: A Case Report

1Neuro and spine surgery department, Hanoi Medical University Hospital, Ha noi, Viet Nam.

2Hanoi Medical University, Ha noi, Viet Nam.

*Corresponding Author: Tan Hoang Minh, Neuro and spine surgery department, Hanoi Medical University Hospital, Ha noi, Viet Nam.

Citation: Kien T Trung, Tan H Minh, Hung K Dinh. (2023). Posterior only for Approach Total EN Bloc Spondylectomy: A Case Report, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Research, BRS Publishers. 2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2837-4843.brs.23.009

Copyright: © 2023 Tan Hoang Minh, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: May 06, 2023 | Accepted: May 19, 2023 | Published: May 24, 2023

Abstract

Total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) is a surgical technique that removes the tumor in a margin-free surgical resection of an entire vertebral body in primary malignant tumors, which can be used by multiple approaches to surgery and is beneficial in reducing complications and totally removing the vertebral column. Although the primary technique requires maximally exposed normal anatomy, our technique can be applied to many lesions in the lumbar area. We reported the first case in Vietnam with a single malignant spinal tumor that was successfully treated with TES surgery. The patient was admitted to our hospital with the primary complaint of back pain that had not responded to conventional treatment as well as neurogenic bowel dysfunction. He was treated with preoperative embolization and underwent TES in L1 by only one posterior approach. Postoperative histological examination revealed myeloid sarcoma. This technique still has many challenges with lumbar vertebrae lesions due to the complex neuroanatomy and vascular structure.

Keywords: total en bloc spondylectomy; primary malignant tumors; lumbar spine

Introduction

TES is an invasive surgery to remove the entire vertebral body and the posterior components of the vertebral body in primary cancers of the spine, locally invasive tumors such as giant cells, and vertebral body metastases [1,2]. Early and complete surgery reduces recurrence rates, improves quality of life, and is widely accepted by cancer surgeons. With advances in technology, TES is increasingly being indicated, including in patients with invasive lesions outside the vertebral body or multiple vertebral bodies [3]. However, this technique still carries certain risks of complications such as spinal cord injury, pleural effusion, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage after surgery [4]. Furthermore, the complication rate associated with the fusion device has been reported to be approximately 40 percentage after this surgery [5].

In the lumbar spine, total vertebral body resection is a real challenge for surgeons due to the unique anatomical features of this region. The relationship between the vertebral body and the structures of the abdominal cavity increases the risk of vena cava, paravertebral plexus, or bladder injury [6]. Unlike the thoracic spine, where a total vertebral body resection is combined with a nerve root resection, it is necessary in the lumbar spine to expose a wide dissection and remove the nerve roots to preserve lower extremity function. Therefore, with injuries to the lumbar vertebrae, surgeons often use two-stage surgical approaches, anterior or lateral, and posterior access, to completely cut the whole vertebral body [6].

For the first time in Vietnam, we have successfully performed "en block" resection of the lumbar vertebral body on a patient with an L1 vertebral body tumor invading the surrounding soft t.

Case Presentation

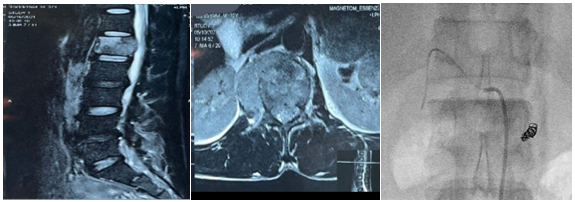

A 37-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital six months ago with symptoms of low back pain. Patients present with urinary retention, straining to urinate, and needing to have a urinary catheter. On magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 1) and computed tomography, there are images of L1 vertebral body resorption lesions with cortical destruction and invasion of the soft tissue adjacent to the right vertebral body. The patient was biopsied at L1 under computed tomography, and histopathology suspected lymphoma or an X-cell tumor.

The patient underwent vertebral body embolization and was operated on one day later.

Figure 1: Magnetic resonance imaging shows lesions in the vertebral body L1 that destroy the cortical bone and invade the surrounding soft tissue. The patient underwent preoperative embolization.

The patient lies prone with a neural operation monitoring system installed. The skin incision follows the midline, interspinous after the vertebrae from T11 to L3. Fix the spine with screws through the two side pedicles (T11, T12, L2, L3). Open the facet joint and part of the T12 posterior arch; completely remove the yellow ligament; expose the dural matter between T12 and L1; do the same with the L1 and L2.

Place the fixed rod on one side; on the opposite side, thread the saw tool from the outside of the T12 L1 foramina through the inner edge of the L1 pedicle down to the L1 L2 foramina out (Figure 2A). Gently unfold the dura sac and place the L1 root protector on both sides. Put the saw wire under the transverse process, down to the base of the L1 pedicle, and then cut the L1 pedicle on one side (Figure 2A). Place the rod on the working side, remove the original rod, and do the same with the remaining pedicle.

Remove the L1 and L2 facet joints on both sides. Lift off the posterior arch with the L1 pedicle on both sides.

Dissect close to the L1 body on both sides to the anterior surface of the vertebral body, dissect to the anterior margin of the anterior longitudinal ligament, and separate the abdominal artery and vena cava from the anterior aspect of the L1 vertebral body (Figure 2B). Remove the posterior longitudinal ligament of the T12L1 and L1L2 disc surfaces, remove the disc capsule, remove the disc, prepare the bone graft from both sides, and remove the anterior longitudinal ligament attached to the anterior surface of the disc (Figure 2C). Mobilize and push the L1 body to the side and remove the entire vertebral body (Figure 2D), while carefully protecting the nerve roots and spinal cord.

Figure 2A: The technique of threading the saw wire through the upper and lower foramina and cutting off the pedicles on both sides; 2B: Dissection of structures around the vertebral body, separation of major blood vessels, and bilateral control of the anterior border of the vertebral body. 2C: Cut the disc above and below the injured vertebrae; 2D: Rotate and remove the entire vertebral body.

After that, the patient was placed in a titanium cage after pedicle screw insertion. The surgery lasted six hours with an intraoperative blood loss of 500 ml. In the process of extracting the spinal cord, there was a tear of the anterior dura, causing a leak of cerebrospinal fluid, but after following the drainage and incision, there was no recurrence of the leak. The patient stood up to walk 48 hours after surgery, was discharged from the hospital after 5 days, and no postoperative complications were recorded. Histopathological results of myeloid sarcoma (myeloid sarcoma).

Discussion

Lièfvre and Stener were the first two surgeons to describe the technique of vertebral resection in cancer [7,8], then Roy Camille popularized it in the 1990s [9]. The term "TES" was described by Tomita and, unlike previous techniques, involves resection of the vertebral body at the level of the pedicle and then resection of the anterior wall and en bloc back wall, minimizing the risk of tumor cell spreading [10]. This surgery is chosen for the treatment of spinal tumors such as vertebral body tumors, osteosarcoma, giant cell tumors, and others because it helps control the tumor, prolonging the mean survival time [9-11].

Our patient's case has an L1 vertebral body tumor in the lumbar spine region. Around the world, the reports of lumbar vertebral discectomy are mostly clinical cases or small patient numbers [12]. The technician performed the procedure using anterior and posterior approaches, especially for lesions below L2, to avoid damaging the nerve roots and removing the nerve roots in this area [13].

The rate of postoperative complications is still high; the most common is the problem of wound healing because the patient has a history of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both; the incision is often long; and the soft tissues next to the incision are often damaged. Hypotrophic, the space left after vertebral body removal [14]. Long operative time is also associated with infection rates and delayed wound healing and is often due to multiple vertebrae involvement, previous surgery, radiation therapy to the previous surgical site, and the need for surgical reconstruction in some patients. With the single posterior incision, it is possible to reduce the time of surgery as well as postoperative complications. The TES reduces the local recurrence rate and prolongs the patient's survival time [9,10].

Conclusion

The TES of the lumbar spine is a very special and challenging technique due to the difficulty of controlling the lumbar anatomy. Therefore, it requires very high skill from the surgeon, and selecting the right patient as well as predicting the complications related to surgery will help increase the success rate of the surgery.

Declarations

Abbreviations

TES: Total en bloc spondylectomy.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from this patient to publish the details of the case.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Authors' contributions:

THM wrote the manuscript. KTT, HKD and THM participated in the surgery

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None

References

- Kato S, Murakami H, Demura S, Yoshioka K, Kawahara N, Tomita K, et al. (2014). Patient-reported outcome and quality of life after total en bloc spondylectomy for a primary spinal tumour. The bone & joint journal, 96(B12):1693-1698.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kato S, Murakami H, Demura S, Yoshioka K, Kawahara N, Tomita K, et al. (2014). More than 10-year follow-up after total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumors. Annals of surgical oncology, 21(4):1330-1336.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Luzzati A, Shah S, Gagliano F, Perrucchini G, Scotto G, Alloisio M. (2015). Multilevel en bloc spondylectomy for tumors of the thoracic and lumbar spine is challenging but rewarding. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 473(3):858-867.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yokogawa N, Murakami H, Demura S, Kato S, Yoshioka K, et al. (2014). Perioperative complications of total en bloc spondylectomy: adverse effects of preoperative irradiation. PloS one, 9(6):e98797.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Matsumoto M, Watanabe K, Tsuji T, Ishii K, Nakamura M, Chiba K, et al. (2011). Late instrumentation failure after total en bloc spondylectomy. Journal of neurosurgery Spine, 15(3):320-327.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sciubba DM, De la Garza Ramos R, Goodwin CR, Xu R, Bydon A, Witham TF, et al. (2016). Total en bloc spondylectomy for locally aggressive and primary malignant tumors of the lumbar spine. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 25(12):4080-4087.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lièvre J, Darcy M, Pradat P, Camus J, Bénichou C, Attali P, et al. (1968). Tumeur à cellules géantes du rachis lombaire; spondylectomie totale en deuz temps [Giant cell tumor of the lumbar spine; total spondylectomy in 2 states]. Revue du rhumatisme et des maladies osteo-articulaires, 35(3):125-130.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Stener B. (1971). Total spondylectomy in chondrosarcoma arising from the seventh thoracic vertebra. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume, 53(2):288-295.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Roy-Camille R, Saillant G, Mazel C, Monpierre H. (2006). Total vertebrectomy as treatment of malignant tumors of the spine. La Chirurgia degli organi di movimento. 75(1S):94-96.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tomita K, Kawahara N, Murakami H, Demura S. (2006). Total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumors: improvement of the technique and its associated basic background. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association, 11(1):3-12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Amendola L, Cappuccio M, De Iure F, Bandiera S, Gasbarrini A, Boriani S. (2014). En bloc resections for primary spinal tumors in 20 years of experience: effectiveness and safety. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society, 14(11):2608-2617.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Clarke MJ, Hsu W, Suk I, McCarthy E, Black J, Sciubba DM, et al. (2011). Three-level en bloc spondylectomy for chordoma. Neurosurgery, 68(2S):325-333.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kawahara N, Tomita K, Murakami H, Demura S, Yoshioka K, Kato S. (2011). Total en bloc spondylectomy of the lower lumbar spine: a surgical techniques of combined posterior-anterior approach. Spine, 36(1):74-82.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kim JE, Pang J, Christensen J, Coon D, Zadnik P, Wolinsky J, et al. (2015). Soft-tissue reconstruction after total en bloc sacrectomy. Journal of neurosurgery Spine, 22(6):571-581.

Publisher | Google Scholor