Case Report

Magnitude of Teenage Pregnancy and Its Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care in Public Health Facilities, Woliso District, Ethiopia, Supported by Qualitative Study

- Bacha Merga Chuko 1*

- Fikru Assefa Kibrat 1

- Zufela Sime Gari 2

- Alemnesh Tesfaye Yirgu 3

- Eshetu Ejeta(PhD) 4

- Shambal Negese Marami 5

- Fayera Gabisa 6

1Department of maternity and neonatology, Ameya Primary Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

1Department of Anesthesia, Waliso General Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

2Departments of Midwifery, Waliso General Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

3Departments of Public Health, Waliso Health Center, Waliso, Ethiopia.

4Department of Public Health, College of health sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia.

5Department of midwifery, College of health sciences, Metu University, Metu, Ethiopia.

6Department of Public Health, College of health sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Bacha Merga Chuko, Department of maternity and neonatology, Ameya Primary Hospital, Waliso, Ethiopia.

Citation: M. C. Bacha, A. K. Fikru, S. G. Zufela, T. Y.Alemnesh, E. Eshetu et al. (2024). Magnitude of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Public Health Facilities, Woliso District, Ethiopia, Supported by qualitative study. Journal of BioMed Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 5(2):1-14. DOI: 10.59657/2837-4681.brs.24.094

Copyright: © 2024 Bacha Merga Chuko, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: June 14, 2024 | Accepted: July 18, 2024 | Published: July 29, 2024

Abstract

Introduction: Teenage pregnancy is a worldwide issue raising concerns for all who are interested in the health and well-being of women and their children. It carries major health and social issues with medical and psychosocial consequences for both women and society in general. Despite the issue is widespread, no prior research has been done in Wolesi district.

Objectives: To assess the magnitude of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Wolesi district, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023.

Methods: A health facility-based cross-sectional study supplemented by qualitative study was conducted from April 1-30/2023. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select 341 pregnant. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire and entered by using Espino version 7.2.5. Independent variables with p-values < 0.25 in bivariable analysis were transferred to multivariable in bivariate logistic regression model. Adjusted odds ratio with its 95 % confidence interval was reported, and the p-value < 0.05 was considered to declare statistically significant in the multivariable model.

Result: Out of total of study participants 324 women completed the interviews giving a response rate of 95%. Magnitude of teenage pregnancy was 62 (19.1%) [95% CI: 15-24%]. Multiple partner (AOR = 5.204 (95%CI: 2.098-12.908), know time of taking emergency contraceptive (AOR = 3.795 (95%CI: 1.203-11.970), women who didn`t discuss Sexual and reproductive health issues with parents (AOR = 2.7 (95%CI: 1.385- 5.265), and being active on social media (AOR = 3.565 (95%CI: 1.692-7.509) were significantly associated with teenage pregnancy.

Conclusion and Recommendation: The magnitude of teenage pregnancy was high and multiple partners, time of taking emergency contraceptive, parents discuss Sexual and reproductive health issues, and active on social media were found strong factors associated with teenage pregnancy. Health facilities managers and health care providers have to work hard together to reduce teenage pregnancy.

Keywords: teenage pregnancy; associated factors; pregnant women; wolesi district; ethiopia

Introduction

Teen pregnancy is a pregnancy in females between the ages of 13 and 19 years. The term is typically used to define females who become pregnant but have not attained the appropriate legal age [1]. It has been a global major public health problem for a long time and it still exists in significant magnitude in today's society. Pregnancy during teenage undermines victim females' rights, harms their reproductive and sexual health [2]. Teenage pregnancy is more common in low- and middle-income countries [3]. Females living in low socioeconomic status, in rural areas, not attending school, getting married young, not having open communication with parents about adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues, and a family history of teen pregnancy are at high risk for teenage pregnancies [4]. Teenage pregnancy affects female teenagers, their neonate, families, and communities in both developed and developing countries [5]. It seriously affects the health and welfare of young mothers and their offspring. Pregnancy and childbirth in teenagers are linked to increased risks of maternal mortality and morbidity, especially in very young teenage girls [6,7]. Teenage pregnancy can also have negative social effects on women [8]. Unmarried pregnant teenage female may face stigma or rejection by parents and peers and threats of violence. They are more likely to experience violence within a marriage or partnership [9]. On the other hand, it is likely for further population growth [10]. It has a negative impact on community development, particularly through perpetuating the cycle of poverty [11].

Numerous intervention strategies to end teenage pregnancy has been tried to overcome the above factors internationally and nationally. Improving policy and legal environment to protect adolescent and young people’s rights, improve access to quality SRH, protection and education services for adolescents and young people, Comprehensive age-appropriate information and education for adolescents and young people are some of the intervention strategies tried [12]. Generally, teenage pregnancy is a problem from the standpoint of both public health and human rights since it has negative long-term effects on girls' physical, psychological, economic, and social status. It has a negative impact on future earning potential and makes victim girls and their families permanently poor. Such negative impacts continue throughout a teenager’s entire life and carry over to the next generation [13].

Globally, 1 million females under the age of 15 and 16 million women between the ages of 15 and 19 become pregnant every year. Teenage females between the ages of 15 and 19 give birth on average 50 per 1,000 females worldwide, or 11% of all births [14]. Sub-Saharan Africa leads the charts of adolescent pregnancies compared to European and North American nations with an estimated prevalence of 19.3% [15]. The overall prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia was ranged from12.80%-30.2% [16-18].

Females with teen pregnancy are at increased risk of preeclampsia, preterm premature rupture of the membrane (PPROM), increased incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension, anemia, sexually transmitted diseases, operative vaginal deliveries (forceps/vacuum), fistula, develops sepsis postpartum depression, and maternal deaths [19]. The risk of maternal mortality is highest for adolescent girls under 15 years old and complications in pregnancy and childbirth are higher among adolescent girls age 10-19 compared to women aged 20-24. Young adolescents (ages 10-14) face a higher risk of complications and death as a result of pregnancy than other women. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are among the leading causes of death for girls aged 15–19 years globally [20]. The children that teenagers bear experience higher levels of birth complications, poor health outcomes and deprivation. Babies of teenage mothers are 50% more likely to be preterm baby, low birth weight, fetal development restriction, severe neonatal condition, stillborn, die early, or develop acute and long-term health problems [19]. Teenage pregnancy involves a number of long-term issues that have an impact on both the females and their community. It causes them to have lower levels of educational achievement, exposure to diseases, and financial difficulties. Consequences related to behavior, finances, and society include smoking, drinking, or using drugs while pregnant, not using antenatal care, arriving late for checkups, and seeking unsafe abortions. Teenage mothers are also more likely to drop out of school, remain single or unemployed, and live-in poverty [21]. Global population growth is accelerated by women who have their first child in their teen years because early pregnancy lengthens the reproductive cycle and increases fertility. Rapid population growth is likely to reduce per capita income growth and well-being, which tends to increase poverty. It traps individuals, communities and even entire countries in poverty [22].

The previous study showed that, residency, maternal education, partner education, lack of parent-to-adolescent communication on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues, marital status, and inadequate opportunity in the community level for positive youth development, illiteracy, and limited employment opportunities and age at mirage and contraceptive utilization were the main determinants of teenage pregnancy [5,23-28]. Teenage pregnancy significantly affects teenage females` life [14]. It restricts the right to education, increasing the likelihood that they will be unemployed. These can result in a variety of challenges, stress, and anxiety throughout the mothering process, which can reduce the young mother's capacity for self-efficacy [29,30]. This indicates that teenage pregnancy and its associated factors were not sufficiently assessed to address the issue by the prior research projects by using quantitative study approach. There is a little research on the teenage pregnancy and its associated factor has been done in the study area woliso district and this study was conducted by using mixed study approach to assess detail associated factors with teenage pregnancy. The aim of this study is to assess the magnitude of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among pregnant women in Woliso district, Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Area and Period

The study was conducted in the Woliso district. Woliso district is located in the South West Shoa Administrative Zone, Oromia regional states of Ethiopia. Woliso town is the capital town of the Woliso district. It is 114 kilometers far away from Addis Ababa to the southwest direction on the main road to Jima town. Based on the 2007 National Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA) projection, the total populations of the district are 208,520, and 43,442 total households. Among the total population, 106,345 are female and 102,175 are male. In the district, there are 35 rural and 3 urban kebeles, 10 Public health centers namely Kora Health Center, Dilala Health Center, Korke Health Center ,Obi Health Center ,Garbo Health Center, Dire Dulati Health Center, Karu simala Health Center, Chiracha Health Center ,Dasejabo Health Center , and Tombe Health Center. Of 38 Public satellite health posts, 2 private medium clinics, 5 private primary clinics, and 1 rural drug vendor. The study was conducted from April1-30 /2023.

Study Design

A facility-based, cross-sectional study design was supplemented by a qualitative study / convergent parallel study design.

Source population

All pregnant women who were attending antenatal care at all public health facilities in Woliso district. Study population was randomly selected or sampled pregnant women who come to public health center to attend antenatal care during the study period. for qualitative study womens who got pregnancy during teenage.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

All pregnant women who came to public health facilities found in Woliso district to attend antenatal care during the study period was included.

Exclusion Criteria

Pregnant women who came to the public health centers found in Woliso district to attend antenatal care but unable to communicate due to any illness. A pregnant woman who came for delivery at the last ANC or referred from other districts to study area was excluded.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was calculated by using single proportion population formula for the first objective, by using the assumption of a 95% confidence interval with a marginal error of 5%, The proportion of teenage pregnancy was 30.2% (0.302), based on a previous study conducted in Kersa District, East Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia (17)

n= (Zα/2)2 P (1-p)

d2

Where n= number of the study subjects

Z= is standardized normal distribution value for the 95% confidence interval (1.96)

P = teenage pregnancy (30.2%)

q=1-p =1-0.302 =0.698 p=0.302 and q =0.698

d = the margin of error taken as 5% = 0.05

z =1.96, p = 0.302, 1-p = 0.698, d = marginal error = 0.05

Therefore, n= (1.96)2 * 0.302 * 0.698 = 324

(0.05)2

By adding 5% (17) non-response rates the final sample size required for this study was 341.

For the second objective, proportion of major associated factors those increase teenage pregnancy are calculated using Epi info 2.7.5 by double population proportion, 80% power, 95% CI using identified associated factors with teenage pregnancy in previous study such as use of contraceptive (31), Educational status (32), and Substance abuse(33).By comparing all sample size, large sample was taken; therefore the final sample size for this study was 341.

For the qualitative study

Sample size was determined after ideas of women were got saturated and 13 women were included in the study

Sampling technique

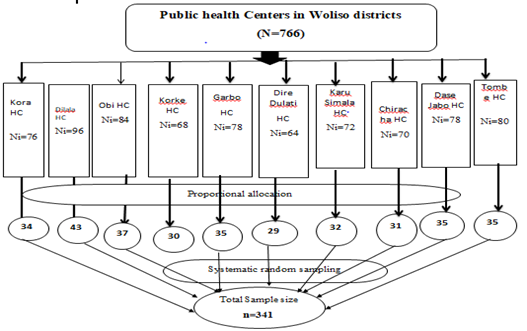

The study was conducted in all public health centers found in the Woliso district. Last year six months ANC reports were 456 at Kora Health Center, 576 at Dilala Health Center,408 at Korke Health Center ,504 at Obi Health Center ,468 at Garbo Health Center, 384 at Dire Dulati Health Center, 432 at Karu simala Health Center ,420 at Chiracha Health Center ,468 at Dasejabo Health Center, and 480 atTombe Health Center. To allocate sample size to public health centers an average of one-month last year ANC report was used. Then one-month last year ANC report of all public health centers (N) was divided by total sample size (n) to obtained the interval (K), K= N/n, K= 766/341, k=2.24 2. The first study participant was determined by lottery methods.

2. The first study participant was determined by lottery methods.

Then, by using a systematic random sampling method the data collectors interviewed women every two-interval daily at the time of finish services, but before leaving the health centers until the required sample size was obtained. Allocate the sample size to each health center. Any pregnant women selected for the study and not willing to participate in the study was counted as non-respondent.

Proportional allocation: allocating sampling proportional to the total population of each public health centers using The formula: ni = Ni/N * n

Where n = total sample size to be selected; N = total population of all health centers; Ni = total population of each public health centers; ni = sample size from each public health centers

Figure 1: Schematic representation of sampling procedure of pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, woliso district, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023.

For qualitative part of the study

purposive sampling technique was used according to women`s willingness to participate in IDI

Study Variables

Dependent Variable

Teenage pregnancy

Independent Variables

Socio-Demographic characteristics: age of teenage girl, Place of residence, educational status, occupation status, marital status, and Parents alive. Behavioral related factors: age at first sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, Age at marriage; learn Sexual education in class and contraceptive use. Familial related factors: living with biological parents, Rh discussion and physical neglect. Social factor: peer pressure, sexual abuse, and exposure to social media.

Operational Definitions

Teenage female: females who are between the ages of 13 – 19 years. Their age will be derived by calculating the age of selected pregnant women at first birth day with their age at the time of the survey.

Teenage pregnancy: pregnancy in teenagers aged 13–19 years among pregnant women and come to selected health facility to attend antenatal care. It is a composite binary outcome variable that refers to pregnancy experience of a woman between 13–19 years. Then it was categorized as 0 = no pregnancy between 13 – 19 years and 1 = pregnancy experienced between the age 13 – 19 years from their birthday.

Pregnant women: all women with confirmed pregnancy who will come to selected health center to attend antenatal care during the study period(32)

Data Collection instrument and Technique

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was adapted after reviewing different kinds of similar literature (3,17,22,30,31,33–35). The questionnaire consisted of 11 items of behavioral factors, 4 items of Familial factors, 4 items of social factors and 10 items of Socio-demographic related factors. The questionnaires contain 4 parts and 29 items.

For the qualitative part of the study: The qualitative data was collected by using a semi-structured interview guide with probing questions linked to teenage pregnancy. During the in-depth interview, voice recorded and notes were taken. The questionnaires contain 3 guiding questions and 9 probing questions. The data were collected using a pre-tested structured face-to-face interview questionnaire prepared by Afan Oromo. Data were collected by trained ten female clinical nurses working in other public health centers and four BSc Nurses were supervised. The data collectors were collected the data by face-to-face interview for all pregnant women came to attend antenatal care at selected health centers at exit time.

Data Quality Control (Assurance)

The Questionnaire was written in English first, and then translated into Afan Oromo as the study units speak Afan Oromo, and finally back to English by language expert to ensure consistency. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for one day on the questions in the questionnaire, interviewing techniques, the study's objectives, and the importance of privacy, discipline, and attitude to interviewees, as well as the respondents' confidentially one week before the actual data collection time. A pre-test was conducted on 5% of teenage female in public health centers in Wanci district at Leman health center which is not found in Woliso district prior to the main study, to test data collection tools and data collectors’ knowledge and appropriate modifications was made. The pre-test data was not included in the main study. Interviewers were strictly supervised at each site by a supervisor. The collected data were checked for completeness, by the investigator and supervisor before data entry into the application and each questionaries approved to enter the application for analysis was correctly coded, and given a specific identification number. Data were entered into Epi info version 7.25 to minimize errors, to check double data entered and design skipping pattern. Outlier and missed data were checked before data analysis by exporting to SPSS version 25. Mult co-linearity was checked by using variance inflation factors, variance inflation factors were ranged 1.03-1.2 and tolerance test was ranged 0.83-0.95. Model goodness of fit was checked by Hosmer – Lermeshows, it was 0.35.

For the qualitative study part

To ensure the quality of data trustworthiness was considered. The fundamental criterion of trustworthiness for qualitative study as follow: Credibility depends upon how closely the collection, presentation and interpretation of data match the underpinning philosophy of the research methodology chosen to address the research question. So, to maintain the credibility, of the research findings IDI guide were evaluated by the professionals, before the data collection. Orientation about the purpose of IDI and responsibility was given before the IDI takes place to avoid unnecessary interruption and keep the rights of the participants.

Transferability is about providing enough information in accessible language to enable another to answer the question to transfer in other setting. To maintain the transferability of the finding, appropriate probes were used to obtain detailed information on responses. To maintain the dependability of the finding the research process member checking was made by returning the preliminary findings to the participants to correct errors and challenge what were perceived as wrong interpretations. Detailed field notes and digital audio recordings were done for all IDI and data analysis in each IDI was crossed checked and the results were reviewed in relation to themes and subthemes with their original data.

Data processing and Analysis

Before the analysis of data clean-up and cross-checking was done. Then it was checked, coded, and entered into SPSS version 21 for analysis. Descriptive analysis (like frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviation) and inferential analysis was done. The bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were done. A p-values less than 0.25 association study variables were transferred to multiple logistic regression models. AOR (adjusted odds ratio) with their 95 % confidence interval was computed, and the p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in the multivariable. The result was presented using text, tables, and charts.

Qualitative data were analyzed thematically by transcribing recorded audio and notes taken during the Interviews. The recorded audio was first transcribed word by word into Afan Oromo, and then translated into English by the language translator. The transcribed data into English was coded manually (color-coded) with similar ideas with the same code. Then, the narrated qualitative information was organized and categorized according to their similar ideas to form sub-themes. Sub-themes emerged together to form the main themes. Then, the study participant's comment was written in quotes. Ideas related to the objective of the study and commonly indicated by women were taken to triangulate the quantitative results and included in the report.

Ethical and Legal Consideration

Ethical approval and clearance were taken from the Ethical Review Board of CMHS Ambo University by Ref. number AU/PGC/720/2015 on the date of 15/05/2015. Support letter was obtained from the Ambo University postgraduate coordinating office to the Woliso District Health Office. A letter of cooperation was secured from the Woliso district health office to selected health centers. Informed verbal consent was obtained from study participants to confirm their willingness to participate after explaining the objectives, benefits, and risks of the study. Participation in the study was voluntary and a study participant has the right to accept or refuse participation in the study at any time. Confidentiality was assured and no personal details will be recorded in any documentation related to this study.

Results

Data were collected from 341 participants, and 324 women completed the interviews giving a response rate of 95%. The 17questionnaires were incomplete and excluded from the analysis.

Socio-Demographic characteristics of the respondents

The mean age of study participants was 25.39 (SD± 6.587) and the mean age of study participants at married was 17.4 (SD± 1.059). More than half of the study participants 158 (56.63%) were married less than 18 years old. One hundred ten (34%) were housewife in occupational status. One hundred ninety-one (59%) of women had attended primary education level (see table 1).

Table 1: Socio-Demographic characteristics of study respondents’ attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

| Variables | Variables Categories | Frequency | Percent |

| Age in year | <15> | 10 | 3 |

| 16-25 | 170 | 52.5 | |

| 26-35 | 110 | 34.0 | |

| >36 | 34 | 10.5 | |

| Residence | Urban | 57 | 17.6 |

| Rural | 267 | 82.4 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 45 | 13.9 |

| Married | 279 | 86.1 | |

| Age of marriage (n=279) | <18> | 158 | 56.6 |

| >=18 years | 121 | 43.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 122 | 37.7 |

| Muslim | 71 | 21.9 | |

| Protestant | 125 | 38.6 | |

| Catholic | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Other (Adventist and wakefata) | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 153 | 47.2 |

| Amhara | 125 | 38.6 | |

| Gurage | 39 | 12.0 | |

| Tigrai | 7 | 2.2 | |

| Educational status | no education | 56 | 17.2 |

| Primary | 191 | 59.0 | |

| Secondary and above | 77 | 23.8 | |

| Occupational status | Housewife | 110 | 34.3 |

| Farmer | 82 | 25.5 | |

| Merchant | 63 | 19.4 | |

| Government employ | 19 | 5.9 | |

| Daily labor | 48 | 14.9 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Partner educational level | No education | 89 | 27.5 |

| Primary | 180 | 55.6 | |

| Secondary | 51 | 15.7 | |

| Tertiary | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Occupational status of partner | Farmer | 82 | 25.3 |

| Merchant | 215 | 66.4 | |

| Government employ | 9 | 2.8 | |

| Daily labor | 15 | 4.7 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.9 |

Behavioral characteristics of the respondents

The minimum age of respondents those started sexual intercourse were 13 years, while the maximum was 33 years with a mean age of 19.92 (SD± 3.739). The minimum parity of respondents was 1 while the maximum was 6 with a mean parity of 1.95 (SD± 0.983). Among the 324 respondents, 285(88%) had no history of engaging in multiple sexual practices. More than three-fourths, 244(75.3%) of the study participants did not know fertile phase of the menstrual cycle. Less than one fourth, 64(19.8%) of women were known the exact time to take emergency contraceptive (see table 2).

Table 2: Behavioral characteristics of the pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

| Variables | Variables Categories | Frequency | Percent |

| Multiple partners | No | 285 | 88.0 |

| Yes | 39 | 12.0 | |

| Know the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle | No | 244 | 75.3 |

| Yes | 80 | 24.7 | |

| Know the exact time to take EC | No | 260 | 80.2 |

| Yes | 64 | 19.8 | |

| Current pregnancy condition | Unplanned | 187 | 57.7 |

| Planned | 137 | 42.3 | |

| heard about FP | No | 135 | 41.7 |

| Yes | 189 | 58.3 | |

| Used at least one method of FP | No | 201 | 62.0 |

| Yes | 123 | 38.0 | |

| family planning method(n=123) | Pills | 30 | 24.39 |

| Depo Provera | 43 | 34.96 | |

| Implant | 20 | 16.26 | |

| IUCD | 20 | 16.26 | |

| Others | 10 | 8.13 | |

| Reason not use family planning | Forced sex | 45 | 22.39 |

| Want to get pregnant | 100 | 49.75 | |

| Lack of family planning | 51 | 25.37 | |

| Others | 5 | 2.49 |

Familial Factors of the respondents

Among the 324 respondents, 200(61.73%) of parents of study participants were married by marital status. More than half, 174 (53.7%) of parents discuss Sexual and reproductive health issues with women. One hundred fifty-eight (51.2%) of respondent’s sisters were got pregnancy during teenage (see table 3).

Table 3: Familial factors of pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

| Variables | Variables Categories | Frequency | Percent |

| Marital status of your parents | Married | 200 | 61.73 |

| Widowed | 40 | 12.35 | |

| Divorced | 34 | 10.49 | |

| Unmarried | 50 | 15.43 | |

| kind of parents | Both biological parents | 284 | 87.7 |

| Either of biological parent | 18 | 5.6 | |

| Guardian/adoptive parents | 22 | 6.8 | |

| Sister pregnant teenager | No | 166 | 51.2 |

| Yes | 158 | 48.8 | |

| Parents discuss Sexual and Reproductive Health issues | No | 150 | 46.3 |

| Yes | 174 | 53.7 |

Social factors of the respondents

Among the 324 of the study participants, 254(78.4%) reported no prior peer pressure. More than two-thirds of the study participants, 236 (72.8%) were not sexually abused. Among 324 respondents, 57(17.6%) were active on social media, from them 43(75.44%) women use at least twice or more a day (see table 4).

Table 4: Social factors of pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

| Variables | Variables Categories | Frequency | Percent |

| peer pressure | No | 254 | 78.4 |

| Yes | 70 | 21.6 | |

| Sexual abuse | No | 236 | 72.8 |

| Yes | 88 | 27.2 | |

| active on social media | No | 267 | 82.4 |

| Yes | 57 | 17.6 | |

| Frequency of social media use (n=57) | At least once a day | 14 | 24.56 |

| At least twice or more a day | 43 | 75.44 |

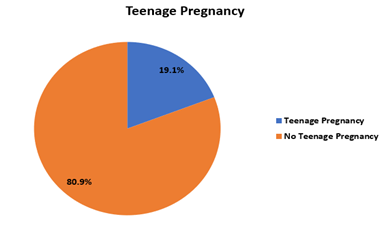

Magnitude of teenage pregnancy

The findings of this study revealed that the magnitude of teenage pregnancies was 62 (19.1%) [95% CI: 15-24%].

Figure 2: Magnitude of teenage pregnancy among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

Factors associated with teenage pregnancy

Bivariable in binary logistics regression analysis

According to this study age of marriage, marital status, educational status of women, residency, multiple partners, knowledge on phase of fertile menstrual cycle, time of taking emergency contraceptive, current condition of pregnancy, parents discuss sexual and reproductive health issues, peer pressure, use of family planning and active on social media were identified as candidate variables for multivariable logistic regression analysis at p value less than 0.25(see table-5).

Table 5: Bivariable binary logistics regression analysis factors associated with teenage pregnancy among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

| Variables | Variables Category | Teenage pregnancy | COR 95% CI | P value | |

| Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | ||||

| Age of marriage | <18> | 18(29.0%) | 44(71.0%) | 2.02(1.067-3.815) | 0.067 |

| >=18 years | 44(16.9%) | 217(83.1%) | 1 | ||

| Residency | Urban | 17(29.8%) | 40(70.2%) | 2.09(1.088-4.005) | 0.034 |

| Rural | 45(16.9%) | 221(83.1%) | 1 | ||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 14(31.1%) | 31(68.9%) | 2.164(1.071-4.373) | 0.21 |

| Married | 48(17.3% | 230(82.7%) | 1 | ||

| Educational status of Girls | No education | 16(28.6%) | 40(71.4%) | 2.68(1.110-6.473) | 0.028 |

| Primary | 36(18.9%) | 154(81.1%) | 1.57(0.735-3.339) | 0.245 | |

| Secondary | 10(13.0%) | 67(87.0%) | 1 | ||

| Multiple partners | No | 47(16.5%) | 237(83.5%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 15(38.5%) | 24(61.5%) | 3.15(1.539-6.455) | 0.002 | |

| Know the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle | No | 52(21.4%) | 191(78.6%) | 1.91(1.01-3.955) | 0.083 |

| Yes | 10(12.5%) | 70(87.5%) | 1 | ||

| Know the exact time to take EC | No | 57(22.0%) | 202(78.0%) | 3.33(1.276-8.688) | 0.014 |

| Yes | 5(7.8%) | 59(92.2%) | 1 | ||

| Used at least one method of FP? | No | 48(24.0%) | 152(76.0%) | 2.46(1.291-4.682) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 14(11.4%) | 109(88.6%) | 1 | ||

| Current pregnancy condition | Unplanned | 45(24.2%) | 141(75.8%) | 2.25(1.226-4.141) | 0.009 |

| Planned | 17(12.4%) | 120(87.6%) | 1 | ||

| Parents discuss Sexual and Reproductive health issues | No | 41(27.3% | 109(72.7%) | 2.72(1.523-4.866) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 21(12.1%) | 152(87.9%) | 1 | ||

| peer pressure | No | 42(16.6%) | 211(83.4%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 20(28.6%) | 50(71.4%) | 2.01(1.086-3.718) | 0.026 | |

| Social media | No | 43(16.6%) | 216(83.4%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 19(29.7%) | 45(70.3%) | 2.17(1.161-4.090) | 0.015 | |

Key 1= Reference COR= Crude odd ratio, CI= confidence interval

Multivariable in binary logistics analysis of Factors associated with teenage pregnancy

After controlling possible confounding variables by multivariable logistic analysis, multiple partners, time of taking emergency contraceptive, parents discuss sexual and reproductive health issues, and active on social media were significantly associated with teenage pregnancy at a p-value <0 AOR = 5.21 AOR = 3.8 AOR = 2.7 AOR = 3.57>

Table 6: Multivariable binary logistics regression analysis factors associated with teenage pregnancy among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health facilities, Woliso district South West Shoa, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023(n=324)

| Variables | Variables Category | Teenage pregnancy |

COR 95% CI | AOR 95% CI | P-value | |

| Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | |||||

| Multiple partners | No | 47(16.5%) | 237(83.5%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 15(38.5%) | 24(61.5%) | 3.152(1.539-6.455) | 5.2(2.1-12.91) ** | 0.0001 | |

| know the exact time to take EC | No | 57(22.0%) | 202(78.0%) | 3.330(1.276-8.688) | 3.8(1.2-11.97) * | 0.023 |

| Yes | 5(7.8%) | 59(92.2%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Parents discuss Sexual and Reproductive health issues | No | 41(27.3% | 109(72.7%) | 2.723(1.523-4.866) | 2.7(1.39- 5.27) * | 0.004 |

| Yes | 21(12.1%) | 152(87.9%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Social media | No | 43(16.6%) | 216(83.4%) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 19(29.7%) | 45(70.3%) | 3.57(1.69-7.51) ** | 0.001 | ||

Key: - *= statistically significant, **= strongly statistically significant,1= Reference, AOR= Adjusted odd ratio, CI= confidence interval

Discussion

Accordingly, to this study, the magnitude of teenage pregnancy was 19.1% [95% CI: [15-24]. The findings of this study were in line with the study conducted in Assosa General Hospital, Ethiopia 20.4% [18]. The probable justification for the observed inline findings might be due to the study design and study setting because both studies were conducted at facility setting. Nevertheless, the findings of current study were higher than the study done at Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia 7.7% [32]. This variation might be due to the study area and study population backgrounds. A study done in Arba Minch Town was carried out at town but this study was done at district area, at where women got unsafe sexual intercourse were not easily got emergency contraceptive pills and limited access to information, accessibility and availability of youth reproductive services especially family planning methods. Another reason may be due to as age women increases the probability of having sexual intercourse and marriage also increases; as a result, the risk of exposure to pregnancy and childbearing also increases. Moreover, the results of present study were higher than study carried out at Bahir Dar City, Northern Ethiopian 12.2% [36]. The variation might be due to study setting. A study done in Bahir Dar City was carried out urban but this study was done at district, so women who were living in urban area were have more chance or access to get contraceptive to prevent pregnancy resulted due to unsafe sexual intercourse than women who living in rural area.

On the contrary, the results of this study were lower than the study conducted in Eastern Ethiopia 30.2% [17]. The possible reason for these discrepancies might be due to variations in the study setting. Since this study was conducted at the facility level, but a study done in Eastern Ethiopia was done at a community level where all women who got pregnant didn’t come to health facility were included. The other probable reason for the observed difference may be due to study period this study was done at the time of accessibility and an availability contraceptive service was improved. Similarly, the findings of this study were lower than the study conducted at Farta woreda, Northwest Ethiopia 25.4% [31]. The possible explanation for the observed difference might be Sociodemographic and cultural differences. On another perspective, this difference may be due to the time gap between studies period because study done Farta woreda, Northwest Ethiopia was done before three years when accessibility and availability of youth reproductive services especially family planning services were low. Additionally, the results of this study were also lower than the study done in Chad 75.6% [34]. The possible explanation for the observed difference might be due to the culture and the study population's background. The other probable reason for the observed difference may be due to study period, but the study done in chad was conducted before five years where accessibility and an availability contraceptive service were low. Moreover, the findings of this study were lower than the study done in India 61% [37]. The differences might be related to study period, and culture of population. The other probable reason for the observed difference might be due to the study area, and background of study population.

This study was found that multiple sexual partners had positive significant association with teenage pregnancy. This was similar to the previous study conducted in Uganda [22]. This may be due to the fact that women who had more sexual partner had the high chance of getting sex at fertile phase of menstrual cycle. This was also supported by qualitative study findings, women who participate in IDI pointed out that there were some factors that associated with teenage pregnancy. Women were got teenage pregnancy were had more partner before got the pregnant. This was supported by the result from IDI: “I was 12 years old when I started having sexual intercourse. At that time, I had a very beloved boyfriend. But I soon broke up with my boyfriend. Then I started relationship with many men and had sex with many men. I finally met a car driver and started doing the same with him for five months, then I got sick up and when I went to the hospital, they told me as I was pregnant” (Respondent 8). Other participants narrated; “I began working in a hotel at the age of 17 after leave my class. I then began having affairs with a lot of males I met right away. When they arrived at the hotel at that time, a lot of men were specifically seeking for me. I discovered I was pregnant two years after I started working” (Respondent 12).

Similarly, the finding of this study showed that, the odds of teenage pregnancy were more times in pregnant women who were not knew time of taking emergency contraceptive than who were knew time of taking emergency contraceptive. This was similar with study conducted in Farta woreda, Northwest, Ethiopia Wolaita Sodo town, southern Ethiopia and In Sub-Saharan Africa [31,33,15]. This might be the fact that proper utilization of contraception can delay the pregnancy until planned, and also from the contraception service they obtained information about the best time to get pregnancy. The other probable justification might be women who use emergency contraceptive after unprotected sexual intercourse had low chance of become pregnant. This was supported by the result from IDI: “I traveled a great distance to go to this health facility. From us, this Health Center is quite far away. Our area does not have another health center. When I was studying, I used to have sex with my friend. Afterwards, though, I used to take an emergency contraceptive pill. However, I didn’t know the exact time of take emergency contraceptive when she was pregnant. Since we weren't around to use emergency contraception timely, my friend and I got married after I became pregnant” (Respondent 3). Other women narrated as; “My friends used to tell me that if you take an emergency contraception after having sex, you won't become pregnant. However, since I live in the countryside, I was able to get an emergency contraceptive after having sex” (Respondent 10).

Additionally, in this study women who were not discuss sexual and reproductive health issues with parents were more likely had teenage pregnancy compared to women who were discuss Sexual and reproductive health issues with thier parents. This was similar with study conducted in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia [38]. Communication between parents and women could enable parents to address challenges of their women and could help women in delaying sexual activity and plan their pregnancy at safe age. This was also supported by qualitative study results, women who participate in IDI pointed out that there were some factors that associated with teenage pregnancy. Women were got not discuss sexual and reproductive health issues with their family had more chance of teenage pregnancy. The following were some of the women`s ideas: “I was raised in a rural area and was informed by my uneducated family to get marriage and go away when I finished the sixth grade. Speaking with my family about sexual and reproductive health issue was shame and traditionally they also not known to discuss about it with me” (Respondent 8). Other women explained by; “It's not traditional known to discuss sexual and reproductive health education in a family, and I have no idea what it is” (Respondent 6).

Furthermore, the odds of teenage pregnancy were high in pregnant women who were active on social media than who were not active on social media. This was similar with study conducted Wolaita Sodo town, southern Ethiopia and in South Africa [5,33]. This might be due to listening and watching social media with content that is not appropriate for their age and motivate them to had unprotected sexual intercourse which may ends with pregnancy. The other reason may be access to social media make them to expose the topics which motivate them to having unsafe sexual intercourse which may result pregnancy.

Strength and limitations of the study

The strength of study this study was conducted in multiple settings and the study used a mixed study approach. The limitation of the study this study was conducted using a cross-sectional study design, which may result in difficulty in providing a causal relationship between teen age pregnancy and independent variables and there could be under-reporting of teenage pregnancy by survey participants due to stigma associated with early sexual activity and pregnancy during teenage they don’t come to health facility.

Conclusion

The Magnitude of teenage pregnancy was high compared to EDHS of 2016. Multiple partners, time of taking emergency contraceptive, parents discuss sexual and reproductive health issues, and active on social media were found strong factors associated with teenage pregnancy.

District health office work hard to arrange the material and program to educate the public and teenage women to avoid risk factors such as consuming media that promotes unsafe sex and promote parents discuss about sexual and reproductive health issues with women. It is better to improve accessibility and availability of youth reproductive services especially family planning service.

Health Care providers work hard on RH services to reduce teenage pregnancy. It is better to give adequate information and counseling on the advantage of using of family planning and giving health education on risk of having multiple sexual partners. The media has high coverage to transmit messages and better if they work on behavioral change on having pregnancy during teenage.

Declaration

What already known on this topic

Magnitude of teenage pregnancy among female students.

This study adds

Magnitude of teenage pregnancy among women.

Identify factors associated with teenage pregnancy among women.

Identify reason of why women getting pregnancy at teenage.

Funding

There is no fund

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict-of-interest respect to this study.

Abbreviations

EC; Emergency contraceptive, FP; Family Planning, HC; Health Centre, OR; Odd Ratio, PPROM; Preterm Premature Rupture of the Membrane, SSA; Sub-Sahara Africa, SPSS; Statistical Package for Social Science and SRH; sexual and reproductive health

Data availability

The corresponding author is willing to provide the dataset that was used in this study based upon reasonable request using’ bachamerga11@gmail.com

Author contribution

All the authors contributed to the proposal development, questionnaires, and data collecting process, analysis, and interpretation.

Data curation by: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Alemnesh Tesfaye Yirgu, Eshete Ejeta, Zufela Sime Gari and Shambel Negese Marami

Format analysis: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, and Fayera Gabisa, Eshete Ejeta, and Shambel Negese Marami

Investigation: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Alemnesh Tesfaye Yirgu, Eshete Ejeta, Zufela Sime Gari and Shambel Negese Marami

Methodology: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Alemnesh Tesfaye Yirgu, Eshete Ejeta, Zufela Sime Gari and Shambel Negese Marami

Revise the manuscript: Bacha Merga Chuko, Fikru Assefa Kibrat, Alemnesh Tesfaye Yirgu, Eshete Ejeta, and Shambel Negese Marami. Final version of the article was checked by all authors.

Consent

Informed consent was taken from every study participant before the actual data collection started.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ambo University, college of health science, Department of Public health and data collectors for their contribution to accomplishing this research

References

- UNFPA. (2016). Fact Sheet: Teenage Pregnancy. United Nations Popul Funds. 1-4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kes A, John N, Murithi L, Steinhaus M, Petroni S. (2017). Economic Impacts of Child Marriage.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Uwizeye D, Muhayiteto R, Kantarama E, Wiehler S, Murangwa Y. (2020). Prevalence of teenage pregnancy and the associated contextual correlates in Rwanda. Heliyon, 6(10):e05037.

Publisher | Google Scholor - United Nation W. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022. 1-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Worku MG, Tessema ZT, Teshale AB, Tesema GA, Yeshaw Y. (2021). Prevalence and associated factors of adolescent pregnancy (15–19 years) in East Africa: a multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 21(1):1-8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Calle M De, Bartha JL, Lopez CM, Turiel M, Martinez N, Arribas SM, et al. (2021). Younger Age in Adolescent Pregnancies Is Associated with Higher Risk of Adverse Outcomes.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wodon Q et al. (20117). Economic impacts of child marriage: global synthesis report. World Bank Gr Int Cent Res Women, 99.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Opoku-Mensah K. (2016). Adolescent Girls’ Resilience to Teenage Pregnancy in the Fanteakwa District.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Vision (2019). The Vıolent ttruth about teenage pregnancy; What children say. World Vis Int, 20-22.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Birhanu BE, Kebede DL, Kahsay AB, Belachew AB. (2019). Predictors of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health, 19(1):1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yussif AS, Lassey A, Ganyaglo GYK, Kantelhardt EJ, Kielstein H. (2017). The long-term effects of adolescent pregnancies in a community in Northern Ghana on subsequent pregnancies and births of the young mothers. Reprod Health, 14(1):1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia moh. (2016). National Adolescent and Youth. Health Strategy, 1:1-100.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Health Organization. (2014). Contraception: Issues in Adolescent Health and Development. WHO Discuss Pap Adolesc, 36.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Asia INS. (2018). Report on the regional forum on adolescent pregnancy, child marriage and early union.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ahinkorah BO, Kang M, Perry L, Brooks F, Hayen A. (2021). Prevalence of first adolescent pregnancy and its associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country analysis. PLoS One, 1-16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tigabu S, Liyew AM, Geremew BM. (2021). Modeling spatial determinates of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia; geographically weighted regression. BMC Womens Health, 21(1):1-12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mezmur H, Assefa N, Alemayehu T. (2021). Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors in eastern ethiopia: A community-based study. Int J Womens Health, 13:267-78.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beyene A, Muhiye A, Getachew Y, Hiruye A, Mariam DH, Derbew M, et al. (2015). Assessment of the magnitude of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenage females visiting, 25-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Noori N, Proctor JL, Efevbera Y, Oron AP. (2022). Effect of adolescent pregnancy on child mortality in 46 countries. BMJ Glob Heal, 7(5):1-12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Neal S, Mahendra S, Bose K, Camacho AV, Mathai M, Nove A, et al. (2016). The causes of maternal mortality in adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 16(1).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Papri FS. (2016). Adolescent Pregnancy: Risk Factors. Outcome and Prevention, 15(1):53-56.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ochen AM, Chi PC, Lawoko S. (2021). Predictors of teenage pregnancy among girls aged 13–19 years in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 19:231-231.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bain LE, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Budu E, Okyere J, Kongnyuy E. (2022). Beyond counting intended pregnancies among young women to understanding their associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Health, 14(5):501-509.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Id MM, Id EK, Auma AG, Akello RA, Kigongo E, Tumwesigye R, et al. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of teenage pregnancy among in-school teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hoima district western Uganda – A cross sectional community-based study, 1-16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Obwaka NN. (2023). The association between the level of education and teenage pregnancy in Kenya A secondary analysis of Kenya Demographic and Health.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumwenda A, Vwalika B. (2017). Outcomes and Factors Associated with Adolescent Pregnancies at the University Teaching Hospital, 44(4):244-249.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Moshi F V., Tilisho O. (2023). The magnitude of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenagers in Dodoma Tanzania: a community-based analytical cross-sectional study. Reprod Health, 20(1):1–13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumar M, Huang KY. Impact of being an adolescent mother on subsequent maternal health, parenting, and child development in Kenyan low-income and high adversity informal settlement context. PLoS One, 16(4):1-17.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cantet N. The Effect of Teenage Pregnancy on Schooling and Labor Force Participation: Evidence from Urban South Africa. (2019). Eff Teenage Pregnancy Sch Labor Force Particip Evid From Urban South Africa, 8(7):77.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Edilberto L, Mengjia L. (2013). Adolescent pregnancy: A Review of the Evidence adolescent pregnancy: A Review of the Evidence. Unfpa.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kassa BG, Belay HG, Ayele AD. Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenage females in Farta woreda, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2020: A community-based cross-sectional study. 1.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mathewos S, Mekuria A. (2018). Teenage Pregnancy and Its Associated Factors among School Adolescents of Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumma WP, Chaka FG, Daga WB, Alemayehu MA, Meskele M, Wolka E. Prevalence of teenage pregnancy and associated factors among preparatory and high school students in Wolaita Sodo town, southern Ethiopia: an institution- based cross- sectional study. 1-8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kassa GM, Arowojolu AO, Odukogbe AA, Yalew AW. (2018). Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Africa: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. 1-17.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Amoateng AY, Ewemooje OS, Biney E. (2022). Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy among women of reproductive age in South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health, 26(1):82--91.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beyene FY, Tesfu AA, Wudineh KG, Wassie TH. (2022). Magnitude and its associated factors of teenage pregnancy among antenatal care attendees in Bahir Dar city administration health institutions, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 22(1):1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shri N, Singh M, Dhamnetiya D, Bhattacharyya K, Jha RP. (2023). Prevalence and correlates of adolescent pregnancy, motherhood and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 1–12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ayele BG, Gebregzabher TG, Hailu TT, Assefa A. (2018). Determinants of teenage pregnancy in Degua Tembien District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A community-based case-control study. 1-15.

Publisher | Google Scholor