Research Article

Knowledge and Practice of Third Year Degree Nursing Students Regarding Postpartum Depression at a University

1University of Namibia, Windhoek.

2School of Nursing and Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, University of Namibia.

*Corresponding Author: Joseph Galukeni Kadhila, School of Nursing and Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, University of Namibia.

Citation: J G Kadhila. (2023). Knowledge and Practice of Third Year Degree Nursing Students Regarding Postpartum Depression at a University. Addiction Research and Behavioural Therapies, BRS Publishers. 2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2837-8032.brs.23.002

Copyright: © 2023 Dr J G Kadhila, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: December 08, 2022 | Accepted: January 20, 2023 | Published: January 24, 2023

Abstract

Introduction: Postpartum depressions (PPD) are common, affecting at least 10% of mothers. PPD is a common illness, the global prevalence being 10–15%. The prevention, detection and treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) are of great importance because PPD without care may cause many problems. Postpartum depressions are serious because of their impact on mother-baby relationships and on the Childs’ Development. However, these depressions seem very insufficiently diagnosed and treated.

Methodology: In this study a quantitative descriptive research design was adopted. Descriptive research design is useful as it helps to obtain information that describes the existing phenomena by asking individuals about their perceptions, attitudes and values. The design reports things the way they are. In this regard, the descriptive research design was used to achieve the main objective of the study which is to assess the knowledge and practice of third year degree nursing students at a University, Windhoek Namibia, regarding postpartum depression.

Result: Participant have good knowledge on, knowledge and practice regarding postpartum depression. An analysis of student’s knowledge about whether physical stress can predispose a woman to PPD revealed that clearly more than half of participants (89.6%, n=60) agreed, while only 9.0% (n=6) of the participants chosen neutral and 1.5%(n=1) disagreed that physical stress can predisposes a woman to PPD.

Conclusion: Descriptive analysis was conducted to compare the knowledge of study participants on postpartum depression. In addition, it shows that only few students who’s disagreed that smoking can predispose woman to PPD. The study revealed that the majority of the participant agreed that physical stress can predispose a woman to PPD. Overall, the study results revealed that above average of the 3rd year nursing students has good knowledge on postpartum depression.

Keywords: Knowledge; students; postpartum; depression; illness; mother-baby

Introduction

Postpartum depressions (PPD) are common, affecting at least 10% of mothers (Serhan et al., 2013). PPD is a common illness, the global prevalence being 10–15%. The prevention, detection and treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) are of great importance because PPD without care may cause many problems. Consequences reported in numerous studies include being distorted emotional and social interaction between infant and mother, insecure attachment and negative consequences to the emotional, cognitive, social and physical development of the child, reportedly persisting up to adolescence. However, these depressions seem very insufficiently diagnosed and treated: some studies have found that about half of these depressions are not recognized by the general practitioner or other health professionals working with the mother and that, among diagnosed mothers, almost a third do not follow the proposed treatment.

Postpartum depression can be considered as a public health problem, not only because of its frequency but also because of its harmful consequences on the newborn, on the conjugal relationship, or even on the family balance. Especially, since it can announce the beginning of a chronic pathology of the mood in the mother. Hence the need for its prevention by action on risk factors, its screening, and its multidisciplinary therapeutic management.

Background

The immediate postpartum period consists of the first twenty-four hours after delivery. Early postpartum starts between the second days after birth until the end of the first week. The postpartum period continues until six weeks or even six months after birth (Romano et al., 2014).

However, evidence suggest that postpartum depression is often overlooked and misdiagnosed and most vulnerable women are rarely recognized during pregnancy or after delivery, thus do not always receive the necessary care (Babatunde, 2010). If one feels empty, emotionless, or sad all or most of the time for longer than two weeks during or after pregnancy, or if they feel like they don’t love or care for their baby, they might have postpartum depression (Ashaba et al., 2015). This usually happens when one is feeling sad, hopeless, and overwhelmed, crying a lot, having thoughts about hurting the baby or themself, not having any interest in the baby, not feeling connected to the baby, or feeling like their baby is someone else’s baby (Albert, 2015).

It is possible to identify women with increased risk factors for postpartum depression, but the unacceptably low positive predictive values of all currently available antenatal screening tools make it difficult to recommend them for routine care.

Literature states that postpartum depression is a debilitating mental disorder with prevalence between 5% and 60.8% worldwide (Klainin & Arthur, 2019). The intensity of feeling inability in suffering mothers is so high that some mothers with postpartum depression comment life as the death swamp Beck et al., (2006) while non-depressed mothers see their baby's birth as the happiest stage of their life (Corwin et al., 2017). The disease manifests as sleep disorders, mood swings, changes in appetite, fear of injury, serious concerns about the baby, much sadness and crying, sense of doubt, difficulty in concentrating, lack of interest in daily activities, thoughts of death and suicide (Norhayati et al., 2015).

In addition, issues such as fear of harming the baby (36%), weak attachment to the baby (34%) and even, in extreme cases, child suicide attempts have been reported (Thorsteinsson et al., 2014). These symptoms have serious effects on family health (Mathisen et al., 2013). Therefore, susceptible people need to be identified before delivery to receive proper care measures. However, the development of screening programs as well as designing evidence-based prevention programs requires principled collection of scientific documentations. However, systematic reviews were seen in the review of some available studies that have assessed the resources in explaining the therapeutic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on postpartum depression (De Crescenzo et al., 2014) and cognitive behavioural therapies (Nardi et al., 2012). Review studies seem to be inadequate, which evaluates the social factors besides addressing biological and psychological factors, while for achieving sufficient knowledge to design screening and preventing programs, all the factors associated with postpartum depression need be evaluated together. Thus, this study aims to assess the knowledge of the nursing students on postpartum depression and the risk factors associated during and after pregnancy.

Aim

The aim of the study was to assess the knowledge and practice of third year degree nursing students regarding postpartum depression at a University, Windhoek, Namibia.

Method

The study adopted a descriptive research design. Descriptive research design is useful as it helps to obtain information that describes the existing phenomena by asking individuals about their perceptions, attitudes and values. The design reports things the way they are. In this regard, the descriptive research design was used to achieve the main objective of the study which is to assess the knowledge and practice of third year degree nursing students of a University, Windhoek, Namibia, regarding postpartum depression. This study used the quantitative approach. Quantitative approach is the mathematical method of measuring and describing the observation of materials or characteristics. Therefore, quantitative approach was used so as to collect numerical data from the respondents.

Quantitative research method is descriptive research that is the collection and analysis of primary information. This research method is aimed at obtaining accurate statistical data. The main advantage of quantitative methods is the coverage of a large number of respondents (Queiros et al., 2017).

Survey

The study applied the use of the primary data collection technique. The responses were achieved through a structured self-administered questionnaire. A specific questionnaire was designed for the purpose of this study to collect data on women’s characteristics and potential risk factors and in English. According to Cohen, Manion, and Keith (2011), questionnaires are reliable because they encourage honesty due to anonymity. The questionnaire was English, straightforward and it is divided in sections. Section A was demographic data that include, gender, age, nationality, higher qualification obtained a marital status. Section B was on the knowledge and practice of the 3rd year nursing students regarding postpartum depression.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was obtained through the structures of the University of Namibia. Therefore, the following ethical considerations were written, informed consent was obtained from each participant after the procedure was explained and risks were pointed out after adequate information were conveyed, possible risks were pointed out. Voluntary participation without penalty for withdrawal was pointed out.

Data collection

The researcher sought permission from the Head of the University of Namibia to collect data from the 3rd year nursing students, once permission was granted, each respondent signed a consent form and the researcher ensured that all ethical procedures were followed. Questionnaires were distributed by the researcher at the University of Namibia main campus and some at the clinical practice, depending on the allocation. Data was collected as from the 1st of August to the 14th August 2022. The researcher collected the questionnaire after participants have completed.

Data analysis Results

Data analysis help to make sense of large numbers of individual responses to communicate the essence of those responses to others, they also aid in summarizing the results, (Brink et al, 2018). The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), software version 26.0 was used to analyze data. Descriptive statistics was used for summarizing the study and outcome variables. They make simple summaries about the sample and the measures. Descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation was used. The study used the following variables including general nurse knowledge of postpartum depression such as, symptoms of postpartum depression, risk factors of postpartum depression, complications and treatments of postpartum depression. Data were presented into bar graphs and a line graph so that it makes sense, after all an experienced statistician was consulted to help with data analysis.

Demographic information

Participant’s age: Participants were asked to indicate their age in the questionnaires as part of the demographic data obtained.

Table 1: Distribution of respondents by age

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation | Variance | |

| Participants Age | 67 | 19 | 49 | 24.67 | 6.568 | 43.133 |

As depicted the minimum rate of age was 19 years, maximum was 49 years old and the mean is 24.67. Participant’s ages were scored and added into a range form which has put the age into categories. The results are presented in the table 1 above.

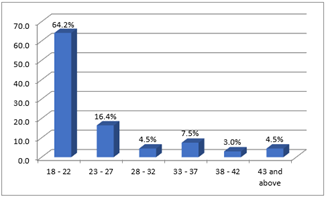

Figure 1: Distribution of participants by age group

Figure 1: above show that the bigger percentage (64.2%) of the participants were between the age group of 18 and 22 years old, followed by 16.4 Percent between the ages of 23 and 27 years; 7.5% of the participants fell between 33 and 37 years, and 4.5% was between the ages 28 and 32, and below 43 years old respectively. Only 3% of the participants were above the age of 38 and 42 years old.

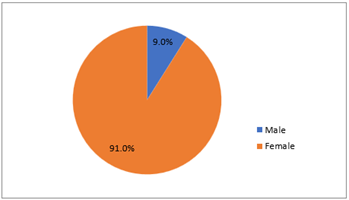

Figure 2: Distribution of respondents by Gender

As seen in figure 2, majority if the participants in the study were female with 91% of the total population and male were 9% of the total population. This means the majority of the participants who were willing to take part and explore their knowledge and practice regarding postpartum depression were female.

Table 2: Participants’ knowledge on postpartum depression

| Variable: Risk factors | Agree | Neutral | Disagree |

| Smoking predisposes a woman to PPD | 24(35.8%) | 31(46.3%) | 12(17.9%) |

| Physical stress can predispose a woman to PPD | 60(89.6%) | 6(9.0%) | 1(1.5%) |

| Genetic makeup can predispose to PPD | 21(31.3%) | 32(47.8%) | 14(20.9%) |

| Age of the mother is a risk factor for PPD | 51(76.1%) | 11(16.4%) | 5(7.5%) |

| Previous history of depression can result in PPD | 49(73.1%) | 15(22.4) | 3(4.5%) |

| Family history of depression can predispose PPD | 34(50.7%) | 24(35.8%) | 9(13.4%) |

| Poor economic status can result in PPD | 52(77.6%) | 8(11.9%) | 7(10.5%) |

| Unplanned and unwanted pregnancy contribute to PPD | 57(85.1%) | 5 (7.5%) | 5(7.5%) |

| Prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with PPD | 53(79.1%) | 12(17.9%) | 2(3.0%) |

Variable 1

Table 2 shows the data regarding the respondent’s knowledge on risk factors on postpartum depression that were collected from 67, 3rd year nursing students from the University of Namibia main campus. The first variable on risk factors, 46.3% (n=31) of the participants had chosen neutral, 35.8 (n=24) of the participants had agreed and 17.9% (n=12) of the participants had disagreed that smoking predisposes a woman to postpartum depression.

Variable 2

On the second variable, 89.6(n=60) of the participants had indicated that they agreed that physical stress is one of the risk factors of postpartum depression, while 9.0% (n=6) of the participants had chosen neutral and 1.5% (n=1) of the participant had disagreed.

Variable 3

Moreover, 47.8(n=32) of the participants had chosen neutral, 31.3(n=21) of the participants had chosen neutral and 20.9% (n=14) of the participant had disagreed that genetic makeup can predispose to postpartum depression.

Variable 4

Moving on to the fourth variable, 76.1(n=51) of the participants had agreed that age of the mother is one of the risk factors of postpartum depression, while 16.4% (n=11) of the participants had chosen neutral and 7.5% (n=5) of the participant had disagreed.

Variable 5

Furthermore, 73.1(n=49) of the participants had agreed that previous history of depression can result in postpartum depression. One the other hand, 22.4% (n=15) of the participants had chosen neutral and 4.5% (n=3) of the participant had disagreed previous history of depression can result in postpartum depression.

Variable 6

On the sixth variable, 50.7% (n=34) of the participants had agreed to that family history of depression can predispose postpartum depression, 35.8% (n=24) of the participants had chosen neutral and 13.4% (n=9) of the participant had disagreed.

Variable 7

Moreover, 77.6(n=52) of the participants had agreed to that poor economic status can result in postpartum depression. One the other hand, 11.9% (n=8) of the participants had chosen neutral and 10.5% (n=7) of the participant had disagreed to that poor economic status can result in postpartum depression.

Variable 8

In addition, 85.1(n=52) of the participants had indicated that they agree that unplanned and unwanted pregnancy contribute to postpartum depression, 7.5% (n=5) of the participants had chosen neutral and 7.5% (n=5) of the participant had disagreed to that unplanned and unwanted pregnancy contribute to postpartum depression.

Variable 9

Final variable, 79.1 %(n=53) of the participants had indicated that they agree that prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with postpartum depression. Also, 17.9% (n=12) of the participants had chosen neutral and 3.0% (n=2) of the participant had disagreed to that prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with postpartum depression.

Table 3: Overall student’s Knowledge on the PPD

| True | False | |

| Psychological morbidity, specifically depression and anxiety, are commonly seen in both the antenatal and postpartum periods | 61(91.0%) | 6(9.0%) |

| Lack of support from healthcare providers can cause postpartum depression | 59(88.1%) | 8(12.0%) |

| Frequent mood swings are one of the requirements for diagnosis of postpartum depression | 60(89.6%) | 7(10.4%) |

| It is not essential to screen for and differentiate between depression and anxiety comorbidity in pregnant women | 9(13.4%) | 58(86.6%) |

| Psychological morbidity, such as depression and anxiety, is not associated with drug and alcohol abuse | 15(22.4%) | 52(77.6%) |

| Postpartum depression most commonly occurs within 10 to 14 days after birth | 54(80.6%) | 13(19.4%) |

| Preeclampsia is associated with depression during pregnancy | 41(61.2%) | 25(37.3%) |

| Mothers may be able to breastfeed while taking antidepressants medication | 52(77.6%) | 15(22.4%) |

| Annoying with your partner or other children symptom of postpartum depression | 51(76.1%) | 16(23.9%) |

Variable 1

On this statement, participants were asked to indicate their view on this statement: ‘psychological morbidity, specifically depression and anxiety, are commonly seen in both the antenatal and postpartum periods’; whereby 91.0% (n=61) of the participants chosen true and 9.0% (n=6) of the participant chosen false.

Variable 2

On this statement, 88.1% (n=59) of the participants chosen true and 12.0% (n=8) of the participants chosen false as their responded to the statement ‘Lack of support from healthcare providers can cause postpartum depression’.

Variable 3

On this statement, 89.6% (n=60) of the participants chosen true ‘frequent mood swings is one of the requirements for diagnosis of postpartum depression. Moreover, 10.4% (n=7) of the participants chosen false.

Variable 4

On this statement, a small number 13.4% (n=9) of the participants in the study chosen true, while 86.6% (n=58) of the participants chosen false to ‘it is not essential to screen for and differentiate between depression and anxiety comorbidity in pregnant women’.

Variable 5

On this statement, 22.4% (n=15) of the participants in the study chosen true to ‘psychological morbidity, such as depression and anxiety, is not associated with drug and alcohol abuse’. However, 77.6% (n=52) of the participants in the study chosen false.

Variable 6

On this statement, more than half (80.6%, n=54) of the participants in the study chosen true, while 19.4% (n=13) of the participants chosen false to ‘Postpartum depression most commonly occurs within 10 to 14 days after birth’.

Variable 7

On this statement, 61.2% (n=9) of the participants in the study chosen true and 37.3% (n=25) of the participants chosen false to ‘preeclampsia is associated with depression during pregnancy’.

Variable 8

On this statement, 77.6% (n=52) of the participants in the study chosen true to ‘mothers may be able to breastfeed while taking antidepressants medication. Moreover, 22.4% (n=15) of the participants in the study chosen false.

Variable 9

On this statement, 76.1% (n=51) of the participants in the study chosen true to ‘annoying with your partner or other children symptom of postpartum depression; while 23.9% (n=16) of the participants in the study chosen false.

Discussion

Demographic data

The demographic characteristics of the participants in this study are presented in Table 1. The study results reveal that majority of the participants (64.2%) were between the ages of 18 - 22 years. The result shows that the female participant dominated in this study. It also shows that, 91.0 %(n=61) of the participants were female, while 9 %(n=6) were male.

Students’ Knowledge on the Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression

The study analyzed of student’s knowledge on the risk factor postpartum depression. It revealed that more 46.3% (n=31) chose neutral as they respond to whether they see smoking predisposes a woman to PPD, 35.8 %(n=24) of the student agreed and 17.9 %(n=12) disagreed that smoking predisposes a woman to PPD, table 3. According to the finding of the study conducted by Adeleke et al (2016) shows that 78.1 (89) of the participants disagreed to that smoking predisposes a woman to PPD and only 21.9% (25) of the participants agreed to that smoking predisposes a woman to PPD.

An analysis of student’s knowledge about whether physical stress can predispose a woman to PPD revealed that clearly more than half of participants (89.6%, n=60) agreed, while only 9.0% (n=6) of the participants chosen neutral and 1.5%(n=1) disagreed that physical stress can predisposes a woman to PPD. According to the study carried out by Grote and Bledsoe (2007) revealed that high level of physical stress significantly causes an increase in depression signs at six months postpartum. The study findings suggested that optimism in woman during pregnancy can reduce depressive symptoms and severity of postpartum depression within the period of six to twelve months after birth.

The study revealed that 47.8% (n=32) of the participants choose neutral as the responses to whether genetic makeup can predispose woman to PPD. In addition, 31.3% (n=21) of the participants agreed to that genetic makeup can predispose woman to PPD and 20.9% (n=14) of the participants disagreed to that genetic makeup can predispose woman to PPD. The finding of the study conducted by Adeleke et al., (2016) shows that 97.4% (111) of the participants disagreed to that genetic makeup can predispose woman to PPD and only 2.6% (3) of the participants agreed to that genetic makeup can predispose woman to PPD.

Regarding whether the participants sees the age of the mother as the risk factor for PPD, 76.1% (n=51) of the participants agreed, 16.4% (n=11) of the participants choose neutral and 7.5% (n=5) of the participants disagreed that age of the mother is the risk factor of PPD. According to Shitu et al., (2019) study results shows that socio-demographic factors like age, educational status, occupation and economic status of the mother were not significantly associated with PPD.

The study result shows that 73.1% (n=49) of the participant agreed that previous history of depression can result in PP, while 22.4% (n=15) of the participants selected neutral to whether previous history of depression can result in PPD and 4.5% (n=3) of the participants disagreed that previous history of depression can result in PPD. Similar study do by Kettunen et al (2014), revealed that 85.2% (n=23) of depressed mothers had a previous history of postpartum depression and only 14.8% (n=4) of depressed mothers did not have previous history of postpartum depression.

The study revealed that 50.7% (n=34) of the participant agreed that family history of depression can predispose PPD, while 35.8% (n=24) of the participants selected neutral and 13.4% (n=9) of the participants disagreed that family history of depression can predispose PPD. The finding of similarly, shows that 58% of mothers, indicated that they had no family history of generalized anxiety disorder or major postpartum depression and 42% of mothers (42%), indicated that they had family history of generalized anxiety disorder or major postpartum depression (Amy, 2016).

Regarding whether the participants sees poor economic status can result to PPD, 77.6% (n=52) of the participants agreed, 11.9% (n=8) of the participants chosen neutral and 10.5% (n=7) of the participants disagreed that poor economic status can result to PPD. These is in contrast with the findings of the study done by Adeleke et al., (2016), which showed that 68.4% (78) of the participants disagreed to that poor economic status can result to PPD and only 31.6% (36) of the participants agreed to that poor economic status can result to PPD.

Study results revealed that 85.1% (n=57) of the participant agreed that unplanned and unwanted pregnancy contribute to PPD, while 7.5% (n=5) of the participants selected neutral and 7.5% (n=5) of the participants disagreed that unplanned and unwanted pregnancy contribute to PPD. However, this was different from study conducted by Adeleke et al (2016) revealed that majority of the participants indicated that unplanned and unwanted pregnancy is not a risk factor for postpartum depression.

The study revealed that 79.1% (n=53) of the participants agreed that prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with PPD. In addition, 17.9% (n=12) of the participants were neutral on whether prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with PPDand 3.0% (n=2) of the participants disagreed to that prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with PPD. The finding of the study conducted by Adeleke et al (2016) revealed that 78.1% (89) of the participants disagreed to that prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with PPD and only 21.9% (25) of the participants agreed to that prenatal anxiety is a risk factor associated with PPD.

Overall Student’s Knowledge on Postpartum Depression

Psychological morbidity, specifically depression and anxiety, are commonly seen in both the antenatal and postpartum periods

On this statement, were asked to indicate their view on this statement: ‘psychological morbidity, specifically depression and anxiety, are commonly seen in both the antenatal and postpartum periods’; whereby 91.0% (n=61) of the participants chosen true and 9.0% (n=6) of the participant chosen false. More research has emphased on mental health issue among women during postnatal period compared to mental health issue among women during antenatal period. According to existing research, an estimate of 12% –16% of women experience postpartum depression. Depression and anxiety of postpartum can be categorized as acute or chronic from the beginning. Similarly, antenatal distress and postnatal distress are said to be related to numerous psychosocial risk factors (Satyanarayana, Lukose, & Srinivasan, 2011).

Lack of support from healthcare providers can cause postpartum depression

On this statement, 88.1% (n=59) of the participants chosen true and 12.0% (n=8) of the participants chosen false as their response to the statement ‘Lack of support from healthcare providers can cause postpartum depression’. According to Who-UNFPA (2008), the attitudes and behaviours of the healthcare providers are of ultimate vital in promoting woman’s mental health during childbirth and mental health in general. Insufficient of social support can cause postpartum depression. Development of postpartum depression in woman may be also caused by other factor such as domestic violence in the form of spouse sexual and physical and verbal abuse. In addition, smoking during pregnancy is a risk factor for developing postpartum depression (Mughal, Azhar, & Siddiqui, 2022).

Frequent mood swings are one of the requirements for diagnosis of postpartum depression

On this statement, 89.6% (n=60) of the participants chosen true ‘frequent mood swings are one of the requirements for diagnosis of postpartum depression. Moreover, 10.4% (n=7) of the participants chosen false. According to Li et al. (2021) study findings mood swings, depression, and anxiety were not found to be risk factors for adverse neonatal outcomes in a country with well-developed welfare systems.

It is not essential to screen for and differentiate between depression and anxiety comorbidity in pregnant women

On this statement, a small number 13.4% (n=9) of the participants in the study chosen true, while 86.6% (n=58) of the participants chosen false to ‘it is not essential to screen for and differentiate between depression and anxiety comorbidity in pregnant women’. According to Schetter & Tanner (2012), in any attempt to screen for and treat depression, anxiety, pregnancy anxiety, or stress in pregnancy, these levels of influence must be considered. For example, involving a woman's partner, closest relative, or friend in follow-up after screening may help her understand or respond to a diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder and accept treatment. Because of their beliefs, values, and level of information, families and communities can undermine or enhance efforts to screen and treat pregnant women.

Psychological morbidity, such as depression and anxiety, is not associated with drug and alcohol abuse

On this statement, 22.4% (n=15) of the participants in the study chosen true to ‘psychological morbidity, such as depression and anxiety, is not associated with drug and alcohol abuse’. However, 77.6% (n=52) of the participants in the study chosen false. The study findings by Mohamed et al. (2020)revealed that majority of the sample for people who use drugs had higher level of depression compared the non-drug users. Also, approximately two thirds of the drug users had high level of anxiety. The study findings showed that there is a positive relationship between substance-related use problems and, depression and anxiety. According to Dr. Cornah (2006), alcohol is associated with a variety of psychological morbidity, such as depression and anxiety.

Postpartum depression most commonly occurs within 10 to 14 days after birth

On this statement, more than half (80.6%, n=54) of the participants in the study chosen true, while 19.4% (n=13) of the participants chosen false to ‘Postpartum depression most commonly occurs within 10 to 14 days after birth’. According to the study carried by WHO-UNFPA (2008) , among large number of women with postnatal depression, their symptoms of postpartum depression last at least for a year. According to a reviewed study, it showed that an estimate of about 30% of women with postnatal depression, symptoms continued for up to a year after giving birth.

Preeclampsia is associated with depression during pregnancy

On this statement, 61.2% (n=9) of the participants in the study chosen true and 37.3% (n=25) of the participants chosen false to ‘preeclampsia is associated with depression during pregnancy’. According to Mbarak et al (2019), postpartum depression is present in one out of five women with pre-eclampsia or eclampsia and the level increased with the severity of the sickness condition. To tackle postpartum depression, efforts ought to be achieved to display screen and grant cure to pregnant woman dealing with pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. The extent of postpartum depression among women with preeclampsia and eclampsia was found increase by 20.5% with the severity of hypertension in pregnancy. When pre-eclampsia or eclampsia detected in younger women, they said to be more likely to suffer from PPD compared to older women.

Mothers may be able to breastfeed while taking antidepressants medication

On this statement, 77.6% (n=52) of the participants in the study chosen true to ‘mothers may be able to breastfeed while taking antidepressants medication. Moreover, 22.4% (n=15) of the participants in the study chosen false. The study conducted by Burt et al (2001) stated that, woman with postpartum depression are often in confusion whether to take antidepressants medication and continue or stop breastfeed their infant. It is vital to protect the mother’s mental health and at the same time optimizing the well-being of the infant, both mentally and physically. Instead of basing the decision of the medication use on the level of serum, the uses of antidepressants by nursing mothers is acceptable as long as the nursing mother closely monitor the clinical status of infants breastfed.

Annoying with your partner or other children symptom of postpartum depression

On this statement, 76.1% (n=51) of the participants in the study chosen true to ‘annoying with your partner or other children symptom of postpartum depression; while 23.9% (n=16) of the participants in the study chosen false. The findings of review done by Ou & Hall (2018) suggested that women's postnatal depression can be coexist with anger. Anger can be directed at oneself as well as at children and family members, which can have a negative impact on relationships.

Limitations

This study was conducted on the 3rd year nursing students from the University of Namibia main campus. The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research (Brutus et al., 2020). Another limiting factor was time, as the students did not have adequate time to participate which hampered the data collection process. The health research committee took long to approve the project hence delaying the researcher to conclude on time. There were some financial constraints to the study because the researcher being a student herself did not have enough funds to print out the questionnaires and also transport fare to reach the participants during data collection period as they were at different health facilities. Moreover, the lack of prior research studies on the topic in Namibia was also a limitation of this study. Additionally, other limitations were that it relied solely on a time point of assessment. For this reason, the results cannot be applied to the entire population of medicine students. The current study's results should not be interpreted subjectively, but they may inform future research on assessing women's postpartum depression knowledge. Future studies can explore more on students’ knowledge on how to care for postpartum depression patients and on proper management postpartum depression.

Conclusion

This study examined the knowledge of 3rd year nursing students regarding postpartum depression. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the statements on a three-point Likert scale ranging from 1=agree, 2=neutral and 3=disagree, regarding the risk factor of postpartum depression. Descriptive analysis was conducted to compare the knowledge of study participants on postpartum depression. In addition, it shows that only few students who’s disagreed that smoking can predispose woman to PPD. The study revealed that the majority of the participant agreed that physical stress can predispose a woman to PPD. Overall, the study results revealed that above average of the 3rd year nursing students have good knowledge on postpartum depression.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to data collection to partake in this study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the School of Nursing and Public Health at the University of Namibia research ethics committee to conduct the study. The following ethical principles, respect for a person, justice, maleficence and beneficence where adhered and respected throughout the study according to guidelines.

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Availability of data materials: Data base is available on a reasonable request from the corresponding author Joseph Galukeni Kadhila.

Competing interest: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding: No funding was done for this work.

Authors' contributions: Wienie Rauha Moongo was responsible for preparing the original draft and writing

Joseph Galukeni Kadhila was responsible for the supervision and editing of manuscript.

Acknowledgements: We would like to acknowledge the third-year nursing students for partaking in our study.

References

- Abdollahi, F., Sazlina, S. G., Zain, A. M., Zarghami, M., Asghari, J. M., & Lye, M. S. (2014). Postpartum depression and psycho-socio-demographic predictors. Asia Pac Psychiatry, 425-434.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ashaba, S., Rukundo, G. Z., Beinempaka, F., Ntaro, M., & LeBlanc, J. C. (2015). Maternal depression and malnutrition in children in southwest Uganda: a case control study. BMC Public Health, 1303.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beck, C. T., Records, K., & Rice, M. (2018). Further development of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs, 735–45.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bloch, M., Daly, R. C., & Rubinow, D. R. (2013). Endocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. Compr Psychiatry, 234-246.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Buttner, M. M., Mott, S. L., Pearlstein, T., Stuart, S., & Zlotnick, C. (2013). Examination of premenstrual symptoms as a risk factor for depression in postpartum women. Arch Womens Ment Health, 219-225.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chatzi, L., Melaki, V., Sarri, K., Apostolaki, I., Roumeliotaki, T., & Georgiou, V. (2013). Dietary patterns during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression: The mother-child ‘Rhea’ cohort in Crete, Greece. Public Health Nutr, 1663-70.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Corwin, E. J., Murray-Kolb, L. E., & Beard, J. L. (2017). Low hemoglobin level is a risk factor for postpartum depression. J Nutr, 4139–42.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Davey, H. L., Tough, S. C., Adair, C. E., & Benzies, K. M. (2017). Risk factors for sub-clinical and major postpartum depression among a community cohort of Canadian women. Matern Child Health J, 866-875.

Publisher | Google Scholor - De Crescenzo, F., Perelli, F., Armando, M., & Vicari, S. (2014). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for post-partum depression (PPD): A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord, 39–44.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ding, T., Wang, D. X., Qu, Y., Chen, Q., & Zhu, S. N. (2014). Epidural labor analgesia is associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression: A prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg, 383-392.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dørheim, S. K., Bjorvatn, B., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2014). Can insomnia in pregnancy predict postpartum depression? A longitudinal population-based study. PLoS One, 946-974.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Douma, S. L., Husband, C., O’Donnell, M. E., Barwin, B. N., & Woodend, A. K. (2015). Estrogen-related mood disorders: Reproductive life cycle factors. ANS Adv Nurs Sci, 364-75.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Feng, Z., Jones, K., & Wang, W. W. (2015). An exploratory discrete-time multilevel analysis of the effect of social support on the survival of elderly people in China. Soc Sci Med, 181-189.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Galvão, J. (2005). Brazil and access to HIV/AIDS drugs: A question of human rights and public health. Am J Public Health, 1110-1116.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Helle, N., Barkmann, C., Bartz-Seel, J., Diehl, T., Ehrhardt, S., & Hendel, A. (2015). Very low birth-weight as a risk factor for postpartum depression four to six weeks postbirth in mothers and fathers:. Cross-sectional results from a controlled multicentre cohort study., 154-161.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Huang, T., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Ertel, K. A., Rich-Edwards, J., & Gillman, M. W. (2015). Pregnancy hyperglycaemia and risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms. . Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 281-289.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hvas, A. M., Juul, S., Bech, P., & Nexø, E. (2014). Vitamin B6 level is associated with symptoms of depression. Psychother Psychosom, 340-343.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jansen, K., Curra, A. R., Souza, L. D., Pinheiro, R. T., Moraes , I. G., & Cunha, M. S. (2017). Tobacco smoking and depression during pregnancy. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul, 44-47.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kheirabadi, G. R., Maracy, M. R., Barekatain, M., Salehi, M., & Kelishadi, M. (2019). Risk factors of postpartum depression in rural areas of Isfahan Province, Iran. Arch Iran Med, 461-467.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Klainin, P., & Arthur, D. G. (2019). Postpartum depression in Asian cultures: A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud, 1355–73.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lancaster, C. A., Gold, K. J., Flynn, H. A., Yoo, H., & Marcus, S. M. (2017). Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 5-14.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lee, D. T., Yip, A. S., Leung, T. Y., & Chung, T. K. (2018). Identifying women at risk of postnatal depression: Prospective longitudinal study. Hong Kong Med J, 349-354.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Leigh, B., & Milgrom, J. (2018). Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry, 24.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ludermir, A. B., Lewis, G., Valongueiro, S. A., & de Araújo TV, T. V. (2013). Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: A prospective cohort study. Lancet, 903-910.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mathisen, S. E., Glavin, K., Lien, L., & Lagerløv, P. (2013). Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in Argentina: A cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health, 787–93.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mayberry, L. J., Horowitz, J. A., & Declercq, E. (2017). Depression symptom prevalence and demographic risk factors among U.S. women during the first 2 years postpartum. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs, 542-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McCoy, S. J., Beal, J. M., Shipman, S. B., Payton, M. E., & Watson, G. (2017). Risk factors for postpartum depression: A retrospective investigation at 4-weeks postnatal and a review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc, 193-198.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Milgrom, J., Gemmill, A. W., Bilszta, J. L., Hayes, B., Barnett, B., & Brooks, J. (2018). Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: A large prospective study. J Affect Disord, 147-157.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nardi, B., Laurenzi, S., Di Nicolò, M., & Bellantuono, C. (2012). Is the cognitive-behavioural therapy an effective strategy also in the prevention of postpartum depression? a critical review. Riv Psichiatr, 205–13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Norhayati, M. N., Hazlina, N. H., Asrenee, A. R., & Emilin, W. M. (2015). Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. J Affect Disord, 34–52.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Silva, R., Jansen, K., Souza, L., Quevedo, L., Barbosa, L., & Moraes, I. (2012). Sociodemographic risk factors of perinatal depression: A cohort study in the public health care system. Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 143-148.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Thorsteinsson, E. B., Loi, N. M., & Moulynox, A. L. (2014). Mental health literacy of depression and postnatal depression: A community sample. Open J Depress, 101–11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zinga, D., Phillips, S. D., & Born, L. (2015). Postpartum depression: We know the risks, can it be prevented? Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 56-64.

Publisher | Google Scholor