Research Article

Knowledge and Its Associated Factors among Nurses Caring Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in Referral Hospital: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study

1Department of Nursing Management; Muhimbili University of Healthy and Allied Sciences 65001, Dar Es Salaam-Tanzania.

2Surgical Department, Xiangya Third Hospital, Central South University – China.

3School of Medicine, Muhimbili University of Healthy and Allied Sciences 65001, Dar Es Salaam-Tanzania.

4Department of Clinical Nursing, Muhimbili University of Healthy and Allied Sciences 65001, Dar Es Salaam-Tanzania.

*Corresponding Author: Emmanuel Sumari, Department of Nursing Management; Muhimbili University of Healthy and Allied Sciences 65001, Dar Es Salaam-Tanzania.

Citation: E Sumari, L Jia, FF Furia, D Mkoka. (2023). Knowledge and its Associated Factors among Nurses Caring Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease in Referral Hospital: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. International Clinical and Medical Case Reports, BRS Publishers. 2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2837-5998.brs.23.012

Copyright: © 2023 Emmanuel Sumari, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 09, 2023 | Accepted: February 23, 2023 | Published: March 02, 2023

Abstract

Background: Nursing care based on expert knowledge of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is currently a major clinical concern. Care to CKD patients provided by non-expert nurses has been reported to result in substandard care, increased risk of complications, and prolonged hospitalization. This study described nurses’ knowledge of the care of patients with CKD, for possible interventions.

Methods: A quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional design; was used; 200 nurses were enrolled by simple random sampling technique. Data were analysed using SPSS version 25; descriptive analysis was done for demographic characteristics and knowledge responses and a chi-square test was conducted to determine association alpha; p<0.05. Also, an ANOVA t-test was done to determine the mean knowledge score difference between the groups of the sociodemographic characteristics p-value < 0.01.

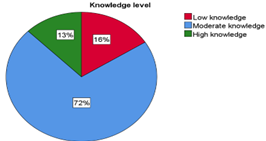

Results: The majority of the participants 72% had moderate and 13% had high knowledge levels. Experience of working in renal ward/unit and attendance in nephrology training were found to significantly contribute to higher mean knowledge scores than not having these experiences [t (198) = -2.26, p=0.025] and [t (198) = -5.24, p<0.01] consecutively. In addition, participants with diplomas, bachelor degree, and masters had higher mean knowledge scores than those with a certificate [F = 17.57, p<0.01].

Conclusion: Knowledge gaps in the care of patients with CKD exist even among nurses working in the highest level of health facilities. Further research may be done to explore nurses’ perceptions on caring for patients with CKD without expert/specialized training.

Keywords: nurses; knowledge; chronic kidney disease; ckd; Tanzania

Introduction

Nephrology nursing care based on expert knowledge of patients with kidney disease remains a public and clinical concern in most countries globally [1,2]. Better care may be a product of good knowledge, experiences, staff motivation, and a well-established infrastructure [1,3]. In Tanzania, although there have been improvements in nephrology services which is considered a great success in the country and the health system at large, nephrology services cannot run with only trained nephrologists and a well-established infrastructure. Nephrologists are still very few to address the population's needs for nephrology services [4].

In Tanzania like many other countries in the world, nurses provide care to CKD patients based on shared experiences and basic knowledge acquired during college or university which may pose threat to individual patient care [4,5,6,9]. Few nurses who are working in dialysis units and renal transplant units attended short time courses (2-3months) overseas most in India and some in Pakistan [4]. Also, nurses receive on-job training for a few weeks to a month in established nephrology units mostly at MNH [4]. This informal and short time training may not be adequate hence nurses may be subjected to the passive role due to a lack of the scientific base of their actions and decisions; making them work under the orders of physicians and renal specialists who have more specialized knowledge power to decide the management rather than a shared decision [10]. In addition, providing care without any formal training to update knowledge and skills may result in substandard care which may be associated with poor quality and outcomes of care such as increased cost of care, prolonged hospitalization, and mortality [7,11,12].

Studies that were done to determine knowledge on CKD either involved different professionals, only non-nephrology nurses, based on one unit like only dialysis nurses and others based only on specific aspects like nutrition to CKD patients [5,6,13,16]. In Tanzania, little is known about nurses in the field of nephrology although nurses play a great role in every stage of CKD prevention including primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention [4]. This study described nurses' knowledge of different aspects of care for CKD patients such as; definition, signs and symptoms, indicators of CKD, treatment options, nutritional consideration, and complications for possible interventions from health and education institution.

Materials and methods

Design

This study used a quantitative cross-sectional design to describe nurses’ knowledge of care and management of patients with CKD, from 1st December 2020 to 30th January 2021.

Study population

Nurses working at Muhimbili National Hospital Dar es Salaam Tanzania where; nurses working at MNH who consented to the study, working in medical, surgical, renal ward, dialysis, ICU, and renal outpatient clinic were included, and those who were from these departments but not providing direct patient care e.g., nurse leaders were excluded.

Sample size and sampling framework

This study involved nurses with different education levels (Enrolled Nurses, Diploma Nurses, bachelor's degrees, and Master's in Nursing). A total of 200 nurses; sample size calculated using Cochran’s formula n = (Z2pq) ÷ e2 [17] using p adopted from a study which was done in Rwanda on Knowledge related to chronic kidney disease (CKD) and perceptions of inpatient management practices among nurses that revealed that only 12% of nurses had good knowledge of CKD [5].

Measurements

Research tool (questionnaire)

Data for this study were collected using a structured English questionnaire was used to assess nurses’ knowledge. This tool was developed by adopting questions from validated research questionnaires that were used to assess the knowledge of CKD among internal medicine residents that had a reliability coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) of 0.69 [18]. Also, some questions were added following a review of studies on knowledge and practice guidelines on the management of CKD [6,16,19,22,23] to fit the study purpose. This questionnaire had 2 sections: Section A: 13 demographic characteristics and Section B: 13 knowledge of CKD questions. The responses to the statements were yes if the statement was correct, no if it was wrong and I don’t know if the participant was not sure whether the statement was right or wrong.

Statistical Analysis

Data for 200 out of 205 contacted participants with; a response rate of 98% were entered, cleaned, and analysed using a statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for windows version 25.0. Descriptive statistical analysis was done, Chi-squared (X2) test was used to determine the association between the demographic/work-related characteristics and participants' level of knowledge; alpha p-value<0>61%= “high”, 41-60= “moderate” and 1-40% as “low” knowledge based on the scale adopted from a study was done in Rwanda to assess nurses' knowledge related to care/management to CKD patients [5]. Texts, tables, and charts were used to present analysed information.

Validity and reliability

To ensure the validity of the research tool, questions for the questionnaire were adapted from the validated tool (Cronbach Alpha =0.69), and added questions were from published studies on the same topic. The Delphi technique [25] was used to validity where the tool was shared with an expert nephrologist and later a pretesting of the tool was done to assess for clarity and usability of the research tool, and the collected information was used to check for the reliability that revealed acceptable results, Cronbach Alpha = 0.859.

Ethical Consideration

The Ethical approval for this study was obtained from, Xiangya Ethical Review Board (ERB) - Central South University China after successful proposal defense and submission; approval number E202048 and local ethical approval from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences following institutional review and approval of the study. Furthermore, informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from each participant; two copies of informed consent were signed. Data was kept secure, only the research team had access; confidentiality and research ethics were adhered to throughout the research process.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

The majority of the participants 105(52.5%) had an age range of 30-40years. Almost half of the study participants were males 101(50.5%). In addition, 93(46.5 percent) of all participants had a diploma level of education followed by 46 percent bachelor's degree. Many participants had work experience of fewer than 5 years 116(58%). Furthermore, the majority of participants in this study were from the medical ward and surgical ward, 74(37%) and 55(27.5%) consecutively.

Also, 101(50.1%) of the participants had no experience of working in the renal ward/unit. Moreover, the majority of the participants 157(78.5%) never attended any nephrology-related training, seminar, or course. Among 44 of the participants who had attended nephrology-related training, 18(40.9%) attended a training called operating dialysis machine followed by 14(31.4%) care of dialysis patients. The majority of the participants who had attended seminars, training, or courses related to nephrology 33 (75%), reported that these training were conducted in less than 5 weeks duration (see table 1).

| Variable | Frequency (N) | Percent (N %) |

| Health facility | ||

| MNH-Upanga | 137 | 68.5 |

| MNH-Mloganzila | 63 | 31.5 |

| Age group | ||

| 20-30 | 72 | 36 |

| 30-40 | 105 | 52.5 |

| 40 and above | 23 | 11.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 101 | 50.5 |

| Female | 99 | 49.5 |

| Highest education level | ||

| Certificate | 10 | 5 |

| Diploma | 93 | 46.5 |

| Degree | 92 | 46 |

| Masters | 5 | 2.5 |

| Working experience | ||

| <5> | 116 | 58 |

| >5 years | 84 | 42 |

| Current ward/unit | ||

| Medical ward | 74 | 37 |

| Surgical ward | 55 | 27.5 |

| Dialysis unit | 33 | 16.5 |

| Renal clinic | 6 | 3 |

| ICU | 32 | 16 |

| Worked in renal ward/unit | ||

| No | 101 | 50.5 |

| Yes | 99 | 49.5 |

| Attended training related to nephrology | ||

| No | 157 | 78.5 |

| Yes | 43 | 21.5 |

| Duration of nephrology training | ||

| <5> | 33 | 75 |

| >5 weeks | 11 | 25 |

| Nephrology training attended | ||

| Managing patients with CKD | 5 | 11.4 |

| Care of dialysis patients | 14 | 31.4 |

| Operating dialysis machine | 18 | 40.9 |

| ICU care of kidney transplant patients | 2 | 4.5 |

| Kidney transplant short course | 1 | 2.3 |

| NESOT conference | 4 | 9.1 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (N=200).

Knowledge related to CKD

Knowledge of definition and risk factors

Knowledge on specific questions related to CKD was also analyzed descriptively, which revealed the study participants were knowledgeable in some areas while in others they were not. Only 50% of the participants were able to identify the statement that best defines CKD and state if CKD is classified in five stages. On the risk factors related to CKD majority of the participants were able to correctly identify the factors; age >60 165(82.5%), severe blood loss/hypovolemia 132(66%), severe diseases/infections (malaria, glomerulonephritis) 182(91%), diabetes mellitus 183(91.5%), obesity 152(76%), systemic lupus erythematosus 104(52%), hypertension 187(93.5%), coronary artery disease 140(70%), renal intoxication (over-use of NSAID, local herbs), 190(95%), family history of CKD 139(69.5%) and smoking 144(72%).

Also, although the majority of the participants were able to identify the 3 conditions mainly associated with CKD in Tanzania, (diabetes 164(82%), severe diseases/infections like malaria, glomerulonephritis 115(57.5%) and hypertension 147(73.5), most of them also incorrectly mentioned other conditions such as age >60 114(57%), severe blood loss/hypovolemia 117(58.5%), obesity 107(53.5%), systemic lupus erythematosus 106(53%), coronary artery disease 107(53.5%), renal intoxication (over-use of NSAID, local herbs), 145(72.5%), family history of CKD 108(54%) which are not commonly associated (see table 2).

Table 2: Knowledge of definition and risk factors (N=200).

| CKD knowledge statements | Correct (N%) | Wrong (N %) |

| Definition of CKD | ||

| No urine output for 1 month with difficulty in breathing | 82(41) | 118(59) |

| GFR>60 with a history of AKI for more than 3 months | 80(40) | 120(60) |

| GFR< 60>3months, ACR >30 mg/g in 2/3 specimens | 135(67.5) | 65(32.5) |

| GFR> 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 >3months, ACR <30> | 100(50) | 100(50) |

| Reduced renal function with proteinuria | 156(78) | 44(22) |

| Stages of CKD | ||

| Chronic kidney disease can be classified into five (5) stages | 100(50) | 100(50) |

| Risk factors of CKD | ||

| Age >60 years | 165(82.5) | 35(17.5) |

| Severe blood loss/hypovolemia | 132(66) | 68(34) |

| Severe diseases/infections (malaria, glomerulonephritis) | 182(91) | 18(9) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 183(91.5) | 17(8.5) |

| Obesity | 152(76) | 48(24) |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 104(52) | 96(48) |

| Hypertension | 187(93.5) | 13(6.5) |

| Coronary artery disease | 140(70) | 60(30) |

| Renal intoxication (over-use of NSAID, local herbs) | 190(95) | 10(5) |

| Family history of CKD | 139(69.5) | 61(30.5) |

| Smoking | 144(72) | 56(28) |

| Three causes of CKD in Tanzania | ||

| Age >60 years | 86(43) | 114(57) |

| Severe blood loss/hypovolemia | 83(41.5) | 117(58.5) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 164(82) | 36(18) |

| Obesity | 93(46.5) | 107(53.5) |

| Severe diseases/infections (malaria, glomerulonephritis) | 115(57.5) | 85(42.5) |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 94(47) | 106(53) |

| Hypertension | 147(73.5) | 53(26.5) |

| Coronary artery disease | 93(46.5) | 107(53.5) |

| Renal intoxication (over-use of NSAID, local herbs) | 55(27.5) | 145(72.5) |

| Family history of CKD | 92(46) | 108(54) |

Knowledge of clinical features and complications of CKD

In addition, many of the participants were able to identify anemia 151(75.5%), hypertension 150(75%), body swelling 183(91.5%), and easy fatigability 144(72%) as signs and symptoms of CKD. However, 102(51), and 101(50.1%) participants failed to identify nocturia and frothy urine respectively as clinical features of CKD. On the complications of a patient with CKD secondary to diabetes, on hemodialysis but uncompliant to the treatment regimen, 143(71.5%), 155(77.5%), 144(72%), and 136(68%) correctly identified anemia, severe infection (sepsis), uremic encephalopathy and diabetic complications like retinopathy and neuropathy respectively. However, many participants also failed to identify bone disease 110(65%), coronary artery disease 101(50.5%) stroke 103(51.5%), and malnutrition 115(57.5%) as possible complications (see table 3).

Table 3: Knowledge of clinical features of and complications of CKD (N=200).

| CKD knowledge statements | Correct (N %) | Wrong (N %) |

| Clinical features of CKD | ||

| Anemia | 151(75.5) | 49(24.5) |

| Hypertension | 150(75) | 50(25) |

| Body Swelling | 183(91.5) | 17(8.5) |

| Easy fatigability | 144(72) | 56(28) |

| Nocturia | 98(49) | 102(51) |

| Frothy Urine | 99(49.5) | 101(50.5) |

| Complications of CKD | ||

| Anemia | 143(71.5) | 57(28.5) |

| Bone disease | 90(45) | 110(55) |

| Severe infection (Sepsis) | 155(77.5) | 45(22.5) |

| Uremic encephalopathy | 144(72) | 56(28) |

| Coronary artery disease | 99(49.5) | 101(50.5) |

| Stroke | 97(48.5) | 103(51.5) |

| Malnutrition | 85(42.5) | 115(57.5) |

| Diabetic complications like retinopathy and neuropathy | 136(68) | 64(32) |

Knowledge of care and management of CKD patients

On investigations necessary to assess the current functioning of the kidney in patients with CKD, many of the participants were able to correctly choose blood pressure 119(59.5%), renal function test 187(93.5%), serum electrolytes 160(80%), full blood picture 140(70%), urinalysis 162(81%) and kidney ureters, bladder (KUB) ultrasound 173(86.5%). Also, 131(65.5%) and 154(77%) were able to identify the Estimated glomerular filtration rate and Urine-albumin creatinine ratio respectively as the test to confirm the diagnosis. However, the participants incorrectly chose urine dipstick 128(64%) and ultrasound and 145(72.5%) as confirmatory investigations. In addition, participants in this study demonstrated understanding of the goals of care or management for CKD patients as the majority were able to choose to reduce cardiovascular risk 142(71%), minimize further kidney injury 173(86.5%), slow the rate of CKD progression 170(85%) and help the patient cope with the disease159(79.5%). However, many participants incorrectly choose that care for CKD patients helps the patient continue with their normal lifestyle and habits121 (60.5%).

Regarding renal replacement therapies, many participants correctly identified intermittent hemodialysis 146(73%) peritoneal dialysis 108(54%), continuous renal replacement therapies 107(53.5%), renal transplant 167(83.5%) as options for patients with CKD at late stages. Also, on the definitive treatment of CKD at late stages, 174(87%) participants correctly chose renal transplant. Furthermore, although the majority of the participants identified renal transplant as the definitive treatment for end-stage of CKD 174(83%), they were also wrong to mention hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis 173(86.5%) and 132(66%) consecutively. On possible interventions that can be used in the management of anemia in patients with CKD, many participants correctly choose blood transfusion 183(91.5%), administration of Erythropoietin (EPO) injection154 (77%), encourage consumption of iron-rich foods173 (86.5%) administration of ferrous sulfate and folic acid 162(81%) (See table 4).

Table 4: Knowledge of care and management to CKD patients (N=200).

| CKD knowledge statements | Correct (N%) | Wrong (N %) |

| Types of renal replacement therapies | ||

| Intermittent hemodialysis | 146(73) | 54(27) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 108(54) | 92(46) |

| Continuous renal replacement therapies | 107(53.5) | 93(46.5) |

| Renal transplant | 167(83.5) | 33(16.5) |

| Definitive treatment of end-stage renal failure | ||

| Hemodialysis | 27(13.5) | 173(86.5) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 68(34) | 132(66) |

| Renal transplant | 174(87) | 26(13) |

| Use of herbals | 167(83.5) | 33(16.5) |

| Treatment of anemia for CKD patient | ||

| Blood transfusion | 183(91.5) | 17(8.5) |

| Administration of Erythropoietin (EPO) injection | 154(77) | 46(23) |

| Encourage consumption of iron-rich foods | 173(86.5) | 27(13.5) |

| Administer ferrous sulfate and folic acid | 162(81) | 38(19) |

Knowledge of diet/nutrition for CKD patients

On statements related to nutrition/diet for CKD patients, the majority of the participants were able to correctly choose that; water intake should not be increased to clear toxins 122 (61%), intake of sodium-containing foods should be reduced/avoided 177(88.5%), intake potassium-rich foods should be reduced 114(57%), the diet of a patient with CKD need special attention; better to be prepared at home174(87%) refined and processed products are not good for the kidney functioning 138(69%) and patient with CKD cannot eat/drink everything if they are on dialysis115(57.5%). However, the majority of participants did not know the role of protein and carbohydrates in CKD as they incorrectly choose protein intake as okay for patients with CKD 122 (61%), and carbohydrate intake should be reduced 112(56%) (See table 5).

Table 5: Knowledge of diet/nutrition to CKD patients (N=200).

| CKD knowledge statements | Correct (N%) | Wrong (N%) |

| Diet/nutrition education for CKD patients | ||

| Increase water intake to clear toxins | 122(61) | 78(39) |

| Reduce/avoid intake of sodium-containing foods | 177(88.5) | 23(11.5) |

| Intake of potassium-rich foods should be reduced | 114(57) | 86(43) |

| Increase intake of carbohydrates | 88(44) | 112(56) |

| Protein intake is okay for proper kidney functioning | 78(39) | 122(61) |

| The Diet of a patient with CKD needs special attention; prepared at home | 174(87) | 26(13) |

| Refined and processed products are not good for the kidney functioning | 138(69) | 62(31) |

| Patients with CKD can eat/drink anything if they are on dialysis | 115(57.5) | 85(42.5) |

Knowledge level

In general, the knowledge score related to the care/management of CKD patients was calculated, with a minimum score of 23 and a maximum of 67. The mean, median, and mode of the knowledge score were 48.7, 50, and 44 consecutively. Knowledge level was calculated out of 100% and referring to figure 1 below, the majority of participants 72% had a moderate level of knowledge and 13% had high knowledge (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Pie chart of the knowledge level.

Association between demographic/work-related characteristics and knowledge level

Referring to table 2 below, the knowledge level of the study participants was found to associate with many demographic or work-related factors. However, some factors including education level (p-value less than 0.01), current working ward/unit (p-value = 0.019), experience of working in renal ward/unit (p-value = 0.007) and attending nephrology related training/short course or seminar (p-value < 0>

Table 6: Association between demographic/work-related characteristics and knowledge level.

| Knowledge level | ||||

| Variables | Low | Moderate | High | p-value |

| Health facility | ||||

| MNH-Upanga | 19(13.9) | 103(75.2) | 15(10.9) | 0.235 |

| MNH-Mloganzila | 13(20.6) | 40(63.5) | 10(15.9) | 0.382 |

| Age group | ||||

| 20-30 | 10(13.9) | 52(72.2) | 10(13.9) | |

| 30-40 | 15(14.3) | 77(73.3) | 13(12.4) | |

| 40 and above | 7(30.4) | 14(60.9) | 2(8.7) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 12(11.9) | 74(73.3) | 15(14.9) | 0.206 |

| Female | 20(20.2) | 69(69.7) | 10(10.1) | 0.001* |

| Highest education level | ||||

| Certificate | 9(90) | 1(10) | 0(0) | |

| Diploma | 14(15.1) | 68(73.1) | 11(11.8) | |

| Degree | 9(9.8) | 69(75) | 14(15.2) | |

| Masters | 0(0) | 5(100) | 0(0) | 0.537 |

| Working experience | ||||

| <5> | 16(13.8) | 84(72.4) | 16(13.8) | |

| >5 years | 16(19) | 59(70.2) | 9(10.7) | 0.019 |

| Current ward/unit | ||||

| Medical ward | 11(14.9) | 56(75.7) | 7(9.5) | |

| Surgical ward | 7(12.7) | 44(80) | 4(7.3) | |

| Dialysis unit | 5(15.2) | 18(54.5) | 10(30.3) | |

| Renal clinic | 3(50) | 3(50) | 0(0) | |

| ICU | 6(18.8) | 22(68.8) | 4(12.5) | 0.007 |

| Worked in renal ward/unit | ||||

| No | 21(20.8) | 74(73.3) | 6(5.9) | |

| Yes | 11(11.1) | 69(69.7) | 19(19.2) | 0.001* |

| Attended nephrology training | ||||

| No | 29(18.5) | 119(75.8%) | 9(5.7) | |

| Yes | 3(7) | 24(55.8) | 16(37.2) | |

Mean knowledge score difference between the sociodemographic variables

Independent sample t-test analysis revealed statistical significance in the mean knowledge score among participants with experience of working in renal ward/units [t (198) = -2.26, p=0.025]. Participants with experience in the renal ward/unit had a higher mean knowledge score (M=50.34, SD =10.39) compared to those with no experience (M=47.15, SD=9.59). Also attending nephrology-related training/courses had a significant mean knowledge score difference among the study participants[t (198) = -5.24, p less than Participants that attended nephrology training/seminar/short course had a higher mean knowledge score (M= 55.44, SD=9.77) compared to those who never attend any nephrology-related training (M=46.89, SD=9.41).

In addition, one way ANOVA test showed that education level had a significant mean knowledge score difference among the participants [F = 17.57, p less than 0.01]. Participants with diplomas (M=49.15, SD=9.57), degree (M=50.36, SD=8.89), and masters (M=51, SD=6.29) had higher mean knowledge scores compared to participants who had certificate level of education (M=28.70, SD= 4.81). There was no statistically significant difference in the mean knowledge score in the other variables (gender, age group, working institution, working experience, and current ward/unit (see table 7).

Table 7: Mean knowledge score difference between the social demographic variables (N=200).

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Statistical value | p-value |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 49.91(9.21) | 1.68^ | 0.09 |

| Female | 47.53(10.84) | 1.33^ | 0.19 |

| Health facility | |||

| MNH-Upanga | 49.37(10.09) | ||

| MNH-Mloganzila | 47.33(10.04) | ||

| Working experience | |||

| <5> | 49.08(9.48) | 0.57^ | 0.57 |

| >5 years | 48.25(10.93) | ||

| Worked in renal ward/unit | |||

| No | 47.15(9.59) | -2.26^ | 0.025 |

| Yes | 50.34(10.39) | ||

| Attended nephrology training | |||

| No | 46.89(9.41) | -5.24^ | 0.001* |

| Yes | 55.44(9.77) | ||

| Age group | |||

| 20-30 | 49.38(9.24) | 1.80** | 0.167 |

| 30-40 | 49.10(10.06) | ||

| 40 and above | 45.00(12.30) | ||

| Education | |||

| Certificate | 28.70(4.81) | 17.57** | .001* |

| Diploma | 49.15(9.57) | ||

| Degree | 50.36(8.89) | ||

| Masters | 51.00(6.29) | ||

| Ward/unit | |||

| Medical ward | 48.05(9.35) | 1.46** | 0.216 |

| Surgical ward | 48.38(9.08) | ||

| Dialysis unit | 51.24(11.93) | ||

| Renal clinic | 41.50(12.66) | ||

| ICU | 49.66(10.64) | ||

Discussion

In this study, the majority of the participants had a moderate level of knowledge, few had low knowledge and very few had a high knowledge level on care and management to CKD patients. This was similar to a study that described nurses' knowledge and reported that only 6% of the participants had good, 55

Limitation of the study

This study was done at the highest level of the health facility where nurses’ knowledge level may not reflect the situation in other high or lower levels of health institutions that receive patients with kidney problems.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that even in high-level health facilities there are knowledge gaps among nurses providing care to CKD patients. The level of knowledge demonstrated by participants in this study may not be enough for nurses to provide quality care for a better outcome to patients diagnosed with CKD as suggested by Alves et al, nurses must have solid knowledge and skills to use technology to provide expert care to CKD patients [3]. Participants knew some parts but also gaps were revealed that call for short and long-term interventions from different stakeholders including health, education, research institutions, and the nursing council.

Statements of Declaration

Consent for publication

The participants provided consent for this study and permission to publish the findings.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests associated with this study.

References

- Effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. J Pediatr. 1994 Aug;125(2):177–88.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cryer PE. Hypoglycaemia: the limiting factor in the glycaemic management of Type I and Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002 Jul;45(7):937–48.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Douillard C, Jannin A, Vantyghem MC. Rare causes of hypoglycemia in adults. Ann Endocrinol. 2020 Jun 1;81(2):110–7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yale JF, Paty B, Senior PA. Hypoglycemia. Can J Diabetes. 2018 Apr;42:S104–8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pratiwi C, Mokoagow MI, Made Kshanti IA, Soewondo P. The risk factors of inpatient hypoglycemia: A systematic review. Heliyon. 2020 May 1;6(5):e03913.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cryer PE. Hypoglycaemia: the limiting factor in the glycaemic management of the critically ill? Diabetologia. 2006 Aug;49(8):1722–5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lacherade JC, Jacqueminet S, Preiser JC. An Overview of Hypoglycemia in the Critically Ill. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009 Nov 1;3:1242–9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bansal N, Weinstock RS. Non-Diabetic Hypoglycemia. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000 [cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK355894/

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR. Evolving Concepts of Myocardial Energy Metabolism. Circ Res. 2016 Nov 11;119(11):1173–6.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ardehali H, Sabbah HN, Burke MA, Sarma S, Liu PP, Cleland JGF, et al. Targeting myocardial substrate metabolism in heart failure: potential for new therapies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012 Feb;14(2):120–9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saito S, Thuc LC, Teshima Y, Nakada C, Nishio S, Kondo H, et al. Glucose Fluctuations Aggravate Cardiac Susceptibility to Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Modulating MicroRNAs Expression. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc. 2016;80(1):186–95.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Snell-Bergeon JK, Wadwa RP. Hypoglycemia, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012 Jun;14(Suppl 1):S-51-S-58.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hedayati HA, Beheshti M. Profound spontaneous hypoglycaemia in congestive heart failure. Curr Med Res Opin. 1977;4(7):501–4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Block MB, Gambetta M, Resnekov L, Rubenstein AH. Spontaneous hypoglycaemia in congestive heart-failure. Lancet Lond Engl. 1972 Oct 7;2(7780):736–8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Benzing G, Schubert W, Sug G, Kaplan S. Simultaneous hypoglycemia and acute congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1969 Aug;40(2):209–16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Khoury H, Daugherty T, Ehsanipoor K. Spontaneous hypoglycemia associated with congestive heart failure attributable to hyperinsulinism. Endocr Pract Off J Am Coll Endocrinol Am Assoc Clin Endocrinol. 1998 Apr;4(2):94–5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yawar Y, Ahmad SP, Irfan M, Saika A. A Rare Case Of Hypoglycemic Unawareness In A Patient With Chronic Congestive Heart Failure. 2019 Jan 1;4(1):20–2.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Potential Risk of Hypoglycemia in Patients with Heart Failure [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ihj/61/4/61_20-134/_article

Publisher | Google Scholor - Moen MF, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Einhorn LM, Seliger SL, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2009 Jun;4(6):1121–7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ahmad I, Zelnick LR, Batacchi Z, Robinson N, Dighe A, Manski-Nankervis JAE, et al. Hypoglycemia in People with Type 2 Diabetes and CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 Jun 7;14(6):844–53.

Publisher | Google Scholor