Research Article

Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Breastfeeding Among Nursing Mothers in Aluu Community, Rivers State, Nigeria

- Anruchi A. Aleru 1*

- Ibe A. Onuah 2

- Chionye Felix-Okpilike 2

- Miriam I. Michael-Nwajei 3

- Ifeanyichukwu Emem 2

- Anthony C. Olobuah 3

1School of Public Health, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

2Department of Surgery, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria.

3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria.

*Corresponding Author: Anruchi A. Aleru, School of Public Health, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

Citation: Anruchi A. Aleru, Ibe A. Onuah, Chionye F Okpilike, Miriam I. Michael-Nwajei, Emem I, et, al. (2024). Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Breastfeeding Among Nursing Mothers in Aluu Community, Rivers State, Nigeria. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(6):1-11. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.24.054

Copyright: © 2024 Anruchi A. Aleru, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: July 01, 2024 | Accepted: July 17, 2024 | Published: July 22, 2024

Abstract

Background: Breastfeeding is vital for infant health and development, yet practices and attitudes vary globally. This study assesses the knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding among nursing mothers in Aluu community, Rivers State, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among 317 nursing mothers residing in Aluu community for at least one year and whose babies were six months and above. A multi-stage sampling method was used to select participants from eight out of nine villages. Data were collected using a semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire, pre-tested for reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.7. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25, with inferential statistics applied to test associations at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

Results: The majority of respondents were aged 18-24 years (40.0%) and married (79.8%). Most participants (74.8%) had attained secondary education, and a significant proportion (42.0%) were involved in trading/business. Knowledge of breastfeeding was generally high, with 55.5% demonstrating good knowledge, particularly regarding the benefits and timing of breastfeeding initiation. However, 44.5% showed poor knowledge of certain aspects, such as the differences between breast milk and cow milk. Attitudes towards breastfeeding were less favorable, with 59.6% exhibiting negative attitudes, particularly regarding public breastfeeding and the perceived impact on physical appearance.

Conclusion: This study highlights the need for targeted interventions to improve knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding among nursing mothers in Aluu community, Rivers State, Nigeria. Such interventions could positively impact breastfeeding practices and infant health outcomes.

Keywords: attitudes; breastfeeding; knowledge; nursing mothers; rivers state

Introduction

Breastfeeding is widely recognized as the optimal method for feeding infants, providing essential nutrients for growth and development, and fostering a strong bond between mother and child. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, followed by continued breastfeeding with appropriate complementary foods for up to two years or beyond [1]. Despite these recommendations, breastfeeding practices vary significantly across different regions and communities, influenced by cultural, socioeconomic, and educational factors. Breastfeeding offers numerous benefits to both infants and mothers. For infants, breast milk provides a complete source of nutrition, supports immune system development, and reduces the risk of infections, allergies, and chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes [2]. For mothers, breastfeeding promotes postpartum recovery, reduces the risk of breast and ovarian cancers, and enhances maternal-child bonding [2,3].

In Nigeria, breastfeeding practices are shaped by a complex interplay of traditional beliefs, healthcare practices, and modern influences. Although breastfeeding is a common practice, exclusive breastfeeding rates remain suboptimal. The Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) of 2018 reported that only 29% of infants under six months were exclusively breastfed [4]. Factors contributing to low exclusive breastfeeding rates include lack of maternal knowledge, cultural misconceptions, and inadequate support from healthcare providers and family members. Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of maternal knowledge and attitudes in shaping breastfeeding practices. A study by Agunbiade and Ogunleye [5] in Southwestern Nigeria found that mothers with higher levels of breastfeeding knowledge were more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding. Similarly, Onah et al. [6] reported that positive attitudes towards breastfeeding were associated with longer breastfeeding duration among mothers in Enugu, Nigeria. These findings underscore the need for continuous education and support to promote optimal breastfeeding practices.

Several barriers to effective breastfeeding have been identified in Nigeria. These include socio-cultural beliefs that favour mixed feeding, lack of knowledge about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, and limited access to breastfeeding support services [7,8]. Additionally, maternal employment and inadequate maternity leave policies often hinder mothers from exclusively breastfeeding their infants for the recommended duration [9]. This study aims to assess the knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding among nursing mothers in the Aluu community, Rivers State. By identifying gaps in knowledge and misconceptions about breastfeeding, the study will provide valuable insights for designing culturally appropriate educational interventions. Furthermore, understanding the attitudes of nursing mothers towards breastfeeding will help in addressing barriers and promoting supportive practices within the community.

Materials and Method

Study Area

This study was carried out in the Aluu community in Ikwerre Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria. Rivers State is in the South-south geopolitical zone of Nigeria. The LGA's headquarters is in Isiokpo, with the LGA comprising several towns and villages. Ikwerre LGA sits on a total area of 1,380 square kilometres with roughly coordinates of 4°:50N 5°:15N, 6°:30E 7°:15E. The estimated population of Ikwerre LGA is put at 211,081 inhabitants with the majority of the area’s dwellers being members of the Ikwerre ethnic affiliation. Ikwerre has a current projected population of 271,700 with a 667.5 km² Area, 407.1/km² Population Density and 2.3% Annual Population Change [4]. The Aluu community is connected to the East-West Road through a major highway. These communities are semi-urban communities characterised by mixed populations. Development has met with the communities due to the influx of people doing various business, students and staff of the University of Port Harcourt and its teaching hospital.

Study Design

It was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted among nursing mothers who reside in the Aluu community.

Inclusion Criteria

- Nursing mothers who were 18 years and above

- Nursing mothers must have lived in Aluu community for at least one year.

- Nursing mothers whose babies are 6 months and above

Exclusion Criteria

- Nursing mothers who are indigenes of Aluu but do not reside in Aluu.

- Nursing mothers who are ill at the time of this study.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was determined using Fisher’s formula outlined by Airaodion et al. [10]: n =

Where: n = Sample size to be obtained; Z = the normal curve that cuts off an area at the tails 1.96 at 95% Confidence Interval; e = is the margin of precision (5%); p = 25% of infants in Africa who were exclusively breastfed [11]; 100-p =q

Sample size (n)

=

=

=

= 288.0 = 288 approximate.

10% non-response:

= 28.8

= 28.8

Total sample size (n) = 28.8 + 288 = 316.8 n = 317 approximated (minimum sample size).

A minimum of 317 participants were recruited for this study.

Sampling Method

Multi-stage sampling method was used in this study.

The different stages include;

Stage 1: Simple random sampling. This involved the selection of 8 villages from the 9 villages in Aluu by simple random sampling method of balloting. Aluu communities are Omuoda, Omuike, Omuigwe, Mgbodo, Omuahunwo, Omuchiorlu, Omuokiri, Omuoko, Omuechie. The 8 villages selected in Aluu were Omuoda, Omuike, Omuigwe, Mgbodo, Omuahunwo, Omuchiorlu, Omuoko, Omuechie. Omuoda Omuigwe, Omuchiorlu, and Omuoko.

Stage 2. Clustered sampling. This involved the clustering of households in each of the selected villages. Proportionate allocation of the sample of 317 to the 8 villages.

Stage 3. Simple random sampling. This involved the identification of households with nursing mothers in each of the 8 selected villages. The households with nursing mothers identified were;

a). Omuike –70, (b). Mgbodo – 83, (c). Omuahunwo – 92, (d). Omuechie – 68,

(e). Omuoda – 89, (f). Omuigwe – 69, (g). Omuchiorlu – 73, (h). Omuoko - 101.

The total number of households in the 8 villages with nursing mothers is 645. Subsequent selection of the allocated sub-sample of nursing mothers by simple random sampling methods of balloting from each of the 8 villages using the identified households with nursing mothers as the sampling frame for each of the villages. Proportionate allocation of the sample of 317 to the 8 villages;

(a). Omuike = = 34.4 ≈ 34

(b). Mgbodo = = 40.79 ≈ 41

(c). Omuahunwo = = 45.23 ≈ 45

(d). Omuechie = = 33. 42 ≈ 33

(e). Omuoda = = 43.74 ≈ 44

(f). Omuigwe = = 33.91 ≈ 34

(g). Omuchiorlu = = 35.88 ≈ 36

(h). Omuoko = 49.7 ≈ 50

Stage 4: The nursing mother was selected by simple random sampling methods of balloting from each of the identified households. Households with more than one nursing mother, the older were selected.

Study Instrument

This study was carried out using a semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was adapted from a published study [12]. The questionnaire was interviewer-administered. The semi-structured questionnaire was divided into 4 sections. Section A was structured to elicit information concerned with the socio-demographic variables of the respondents. Section B was to obtain information on the habitat history of the participants. Section C was to obtain information on the knowledge of breastfeeding of the respondents. Section D was to obtain information on the breastfeeding practice.

Methods of Data Collection/Instrumentation

Data was collected using the semi-structured questionnaire. Data collection was conducted over a period of 4 months. The questionnaire was used to obtain responses from participants who were present on the days of the study. A total of 317 nursing mothers were administered the questionnaire.

Validation of study instrument

The semi-structured questionnaire was pre-tested in the Choba community in Obio/Akpor LGA which shares the same demographic features as the selected communities for this study. The pre-test was done with 32 participants which is 10% of the original sample. The reliability of the questionnaire for this study was assessed using the index of internal consistency calculated with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient Alpha and Conbach’s Alpha score of 0.7.

Data analysis

Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25 was used for the analysis in this study. All returned questionnaires were checked for completeness and adequacy of responses by the participants. The socio-demographic characteristics and other questions from the objectives were changed to numeric codes to enable easy and accurate statistical analysis. Frequencies and percentages were used for the socio-demographic variables of the respondents, habitat history of the participants, knowledge of breastfeeding of the respondents, and breastfeeding practice. The practice of breastfeeding was performed by summing and scoring the questions under each of these sections. Inferential analysis such as the Chi-square test was carried out to test for association between socio-demographic variables, habitat history, attitude and breastfeeding practice was performed. The level of statistical significance between them was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Scoring

Concerning the practice of breastfeeding, 9 questions were used for the assessment. Some questions were; when did you start breastfeeding your child? How long have you breastfed your child? Did you practice exclusive breastfeeding (Months)? If yes to question (3), how long did you/have you practised exclusive breastfeeding (in Months)? Does your baby usually feed from both breasts at each feeding? Does your baby usually let go of the breast him or herself? The score was categorized as poor and good practice. A score of ≤ 4 was classified as poor, ≥ 5 was classified as good practice. The Likert scale were scored as follows; Strongly agree =5, Agree=4, Indifference=3, Disagree=2, Strongly disagree=1

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the University of Port Harcourt. Written Informed consent was obtained from the participants. Strict confidentiality of the information provided by the participants was ensured and they were assured that the information provided will be used solely for this study. This was achieved by not using a participant’s identifier such as a name. Also, the participants received an immediate benefit of health education on breastfeeding.

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents indicate a mean age of approximately 27.88 years, with the majority falling into the 18-24 (40%) and 25-31 (37.2%) age groups. Most respondents are married (79.8%), with smaller percentages being single (6.6%), cohabiting (10%), separated (2.8%), or widowed (0.63%). The dominant tribe among the respondents is Ikwerre (27.1%), followed by Igbo (20.2%) and Yoruba (12.6%). Christianity is the predominant religion (95%), and the majority have secondary education (74.8%). Regarding occupation, 42% are involved in trading/business, 40.4% are unemployed, and 7.6% are employed. Income distribution shows that 40.4% have no income, with significant portions earning between 30,001-60,000 (27.1%) and 60,001-90,000 (22.7%) (Table 1). The habitat history reveals that 87.4% of respondents live in tenement houses, with 70.3% occupying one room. Most households have 2-5 people (87.7%), and all respondents share rooms, predominantly with 2-3 persons (72.6%) (Table 2).

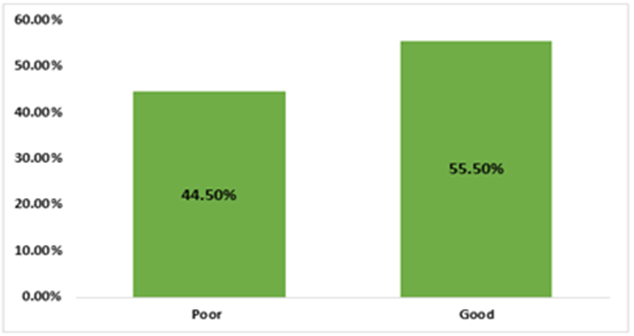

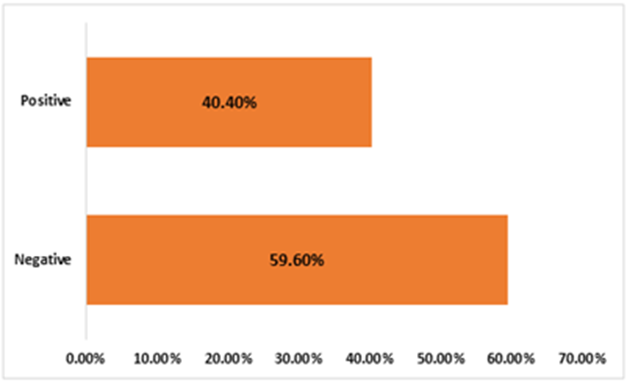

Social history data shows that none of the respondents consume tobacco, and 27.1% consume alcohol, with beer being the most common type (53.5%). The majority (64%) consume alcohol in small quantities, and only 10.1% have been drunk (Table 3). Knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding among respondents is high, with 79.8% having received information about breastfeeding, primarily from health workers (77.9%). Most respondents (79.8%) correctly believe that formula is not healthier than breast milk and that breastfeeding should start immediately after birth (97.5%). There is a significant understanding that breastfeeding should be frequent in the early months and that it provides increased immune function (95%) (Table 4). In terms of attitudes towards exclusive breastfeeding, 55.5% of respondents have a good knowledge level, while 44.5 Percentage have poor knowledge (Figure 2). Attitudes are mixed, with 27.1 Percentage strongly agreeing that infant formula gives more freedom, but 39.4 Percentage believe breastfeeding makes breasts less attractive. The majority (82.3%) believe babies enjoy breastfeeding, and 97.5 Percentage feel it helps mothers feel closer to their babies. Public breastfeeding is seen as acceptable by 54.6 Percentage, though 55.2 Percentage find it embarrassing. Overall, 59.6 Percentage of respondents have a negative attitude towards exclusive breastfeeding, while 40.4 Percentage have a positive attitude (Table 5).

Table 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

| Variables | Frequencies (n=317) | Percentage (%) |

| Age-group (Years) | ||

| 18-24 | 127 | 40.0 |

| 25-31 | 118 | 37.2 |

| 32-38 | 56 | 17.7 |

| ≥39 | 16 | 5.0 |

| Mean =27.88±0.87 | ||

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 21 | 6.6 |

| Married | 253 | 79.8 |

| Separated | 9 | 2.8 |

| Widow | 2 | 0.63 |

| Cohabiting | 32 | 10.0 |

| Tribe | ||

| Delta-Igbo | 8 | 2.5 |

| Efik | 15 | 4.7 |

| Esan | 8 | 2.5 |

| Etche | 8 | 2.5 |

| Igbo | 64 | 20.2 |

| Ijaw | 24 | 7.6 |

| Ikwerre | 86 | 27.1 |

| Itegidi | 8 | 2.5 |

| Ogoni | 24 | 7.6 |

| Okirika | 8 | 2.5 |

| Omuma | 8 | 2.5 |

| Urhobo | 16 | 5.0 |

| Yoruba | 40 | 12.6 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 301 | 95.0 |

| Islamic | 16 | 5.0 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary education | 8 | 2.5 |

| Secondary education | 237 | 74.8 |

| Tertiary education | 72 | 22.7 |

| Current occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 128 | 40.4 |

| Trading/Business | 133 | 42.0 |

| Skilled work (e.g sewing) | 32 | 10.1 |

| Employed | 24 | 7.6 |

| Income | ||

| None | 128 | 40.4 |

| ≤30,000 | 7 | 2.2 |

| 30,001-60,000 | 86 | 27.1 |

| 60,001-900,000 | 72 | 22.7 |

| 90,001-120,000 | 16 | 5.0 |

| ≥120,001 | 8 | 2.5 |

Table 2: Habitat History

| Variables | Frequencies (n=317) | Percentage (%) |

| Type of Accommodation | ||

| Bungalow | 40 | 12.6 |

| Tenement house | 277 | 87.4 |

| Number of Rooms | ||

| 1 room | 223 | 70.3 |

| 2 rooms | 62 | 19.6 |

| 3 rooms | 24 | 7.6 |

| 5 rooms | 8 | 2.5 |

| Number of People in the House | ||

| 2-3 | 136 | 42.9 |

| 4-5 | 142 | 44.8 |

| 6-7 | 39 | 12.3 |

| Share room | ||

| Yes | 317 | 100.0 |

| Share room with | ||

| 1 person | 47 | 14.8 |

| 2 persons | 167 | 52.7 |

| 3 persons | 63 | 19.9 |

| 4 persons | 32 | 10.1 |

| 5 persons | 8 | 2.5 |

Table 3: Social History

| Variables | Frequencies (n=317) | Percentage (%) |

| Consume Tobacco | ||

| No | 317 | 100.0 |

| Consume Alcohol | ||

| Yes | 86 | 27.1 |

| No | 231 | 72.9 |

| Type of Alcohol | ||

| Action Bitters | 16 | 18.6 |

| Beer | 46 | 53.5 |

| Sachet | 9.3 | |

| Guinness | 16 | 18.6 |

| Quantity of Alcohol | ||

| Little | 55 | 64.0 |

| Moderate | 31 | 36.0 |

| Been Drunk | ||

| Yes | 32 | 10.1 |

| No | 285 | 89.9 |

Table 4a: Knowledge of Exclusive Breast Feeding

| Variables | Frequencies (n=317) | Percentage (%) |

| Information about Breast Feeding | ||

| Yes | 253 | 79.8 |

| No | 64 | 20.2 |

| Source of Information | ||

| Health Workers | 197 | 77.9 |

| Family and Friends | 56 | 22.1 |

| Formula is Healthier | ||

| True | 64 | 20.2 |

| False | 253 | 79.8 |

| No Difference between Breast milk and Cow milk | ||

| True | 176 | 55.5 |

| False | 141 | 44.5 |

| Breast feeding starts as child is born | ||

| True | 309 | 97.5 |

| False | 8 | 2.5 |

| Mothers should not help or guide baby to breast feed | ||

| False | 317 | 100.0 |

| First Breast Milk is not good | ||

| True | 128 | 40.4 |

| False | 189 | 59.6 |

| Mothers should Breastfeed 2-3 times in first month | ||

| True | 197 | 62.1 |

| False | 120 | 37.9 |

| Mothers should Breastfeed more than 8 times in 2-6 months | ||

| True | 173 | 54.6 |

| False | 144 | 45.4 |

| Mothers should Breastfeed 2-3 times in 7-12 months | ||

| True | 133 | 42.0 |

| False | 184 | 58.0 |

| Breast feeding with combination of other food | ||

| True | 55 | 17.4 |

| False | 262 | 82.6 |

| Breast feeding should Last Less than 6 months | ||

| True | 101 | 31.9 |

| False | 216 | 68.1 |

Table 4b: Knowledge of Exclusive Breast Feeding

| Variables | Frequencies (n=317) | Percentage (%) |

| Exclusive Breastfeeding less than 6 months | ||

| True | 64 | 20.2 |

| False | 253 | 79.8 |

| Laid Back Breastfeeding position | ||

| True | 285 | 89.9 |

| False | 32 | 10.1 |

| Standing not a breastfeeding position | ||

| True | 16 | 5.0 |

| False | 301 | 95.0 |

| Breastfeeding Provides increased immune function | ||

| True | 301 | 95.0 |

| False | 16 | 5.0 |

| Exclusive Breastfeeding is most Beneficial | ||

| True | 309 | 97.5 |

| False | 8 | 2.5 |

Figure 1: Assessment of Knowledge Exclusive Breast Feeding.

Table 5: Attitude towards Exclusive Breast Feeding.

| Variables | Strongly agree | Agree | Indifference | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| Infant feeding formula gives freedom | 86(27.1) | 32(10.1) | 24(7.6) | 56(17.7) | 119(37.5) |

| Breastfeeding makes breasts less attractive | 125(39.4) | 40(12.6) | 8(2.5) | 24(7.6) | 120(37.9) |

| Breastfeeding makes partner or me less attractive | 56(17.7) | 48(15.1) | 16(5.0) | 77(24.3) | 120(37.9) |

| Babies enjoy breastfeeding | 261(82.3) | 0(0.00) | 16(5.0) | 8(2.5) | 32(10.1) |

| Breast feeding help mothers feel closer to her baby | 309(97.5) | 8(2.5) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) |

| Breast feeding publicly is embarrassing | 72(22.7) | 8(2.5) | 24(7.6) | 38(12.0) | 175(55.2) |

| Breast feeding is acceptable publicly | 173(54.6) | 56(17.7) | 16(5.0) | 0(0.00) | 72(22.7) |

| Decision to breast feeding should be made by both parents | 149(47.0) | 56(17.7) | 8(2.5) | 48(15.1) | 56(17.7) |

| Babies who are breastfed get a better start in life | 277(87.4) | 24(7.6) | 8(2.5) | 8(2.5) | 0(0.00) |

| Women of all educational statuses should breastfeed their children | 285(89.9) | 8(2.5) | 8(2.5) | 32(10.1) | 0(0.00) |

| Women of all socio-economic classes should breastfeed their children | 277(87.4) | 8(2.5) | 0(0.00) | 32(10.1) | 0(0.00) |

| Breastfeeding is more convenient than formula | 237(74.8) | 32(10.1) | 16(5.0) | 24(7.6) | 8(2.5) |

Figure 2: Assessment of Attitude towards Exclusive Breast Feeding.

Discussion

Breastfeeding is a critical component of child nutrition and health, providing essential nutrients and antibodies that protect infants from various illnesses and conditions [5]. Despite its well-documented benefits, breastfeeding practices and attitudes vary widely across different regions and communities. The study sample consisted of 317 nursing mothers, with the majority (77.2%) falling within the 18-31 age range. This demographic is critical as younger mothers often have varying levels of knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding compared to older mothers. The mean age of the respondents was 27.88 years, suggesting a relatively young cohort. Marital status showed that 79.8% of the respondents were married, aligning with the expectation that marital support can positively influence breastfeeding practices [13]. A significant majority of the respondents (74.8%) had secondary education, with 22.7% having tertiary education. Education level is crucial as it often correlates with better breastfeeding knowledge and practices [14]. In terms of occupation, a substantial proportion (40.4%) were unemployed, while 42.0% were engaged in trading or business. The income distribution was skewed towards the lower end, with 40.4% reporting no income and 27.1 Percentage earning between 30,001-60,000 Naira. This economic factor can significantly influence access to breastfeeding information and support [15]. Habitat conditions revealed that 87.4% of the respondents lived in tenement houses, with 70.3% living in a single room. Overcrowding was evident as all respondents shared rooms, often with multiple individuals. These living conditions can impact breastfeeding practices due to a lack of privacy and support [16]. Social habits indicated that 27.1% of the mother’s consumed alcohol, predominantly beer. While none consumed tobacco, alcohol consumption, particularly during breastfeeding, can have adverse effects on both mother and child [17]. The low incidence of drunkenness (10.1%) among respondents suggests moderate alcohol use, yet even moderate consumption can influence breastfeeding outcomes [18].

Several studies provide context for these findings. For instance, in a similar study in Nigeria, Omotola et al. [19] found that younger mothers and those with higher education levels exhibited better breastfeeding practices, consistent with the present study's demographics. Another study by Sriram et al. [15] highlighted the importance of socioeconomic status in breastfeeding success, which aligns with the current findings where lower income and unemployment rates might hinder optimal breastfeeding practices. Habitat conditions in the Aluu community reflect the broader issue of housing quality affecting health behaviours, as documented by Garcia et al. [16]. Overcrowding and shared living spaces can reduce the mother's comfort and ability to breastfeed effectively. Furthermore, the absence of tobacco use is a positive indicator, although alcohol consumption remains a concern, echoing findings by Giglia and Binns [17] regarding the negative implications of alcohol on breastfeeding. The finding that health workers are the primary source of breastfeeding information is consistent with other studies conducted in Nigeria and globally. For instance, Oche et al. [20] found that health professionals were the most influential source of breastfeeding information among mothers in Sokoto, Nigeria. Similarly, studies in other African countries, such as Kenya and Ghana, have reported similar findings [21,22]. The misconception that there is no difference between breast milk and cow milk reported by 55.5% of respondents in this study is concerning and reflects gaps in breastfeeding education. This finding is echoed in other studies where mothers held similar misconceptions about the equivalence of breast milk and other milk forms [23,24]. The belief by 40.4% of respondents that the first breast milk (colostrum) is not good highlights a persistent myth. This is consistent with findings from studies in various regions of Nigeria where cultural beliefs and practices influence perceptions of colostrum [7].

The mixed knowledge regarding breastfeeding frequency is similar to findings from other studies. For example, a study by Ekure et al. [8] found that while most mothers knew about the importance of frequent breastfeeding in the early months, many were unaware of the recommended frequencies as the child grows. The high percentage (97.5%) of mothers recognizing the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding is encouraging and reflects a positive shift in attitudes, which aligns with global trends towards greater acceptance of EBF as reported by the WHO [1]. The results show a mixture of positive and negative attitudes towards exclusive breastfeeding. The table indicates significant skepticism about the aesthetic impacts of breastfeeding, with 39.4% strongly agreeing that breastfeeding makes breasts less attractive, and 37.9% strongly disagreeing. Similarly, 27.1% of mothers strongly agreed that infant feeding formula gives them more freedom compared to breastfeeding. However, there is a notable recognition of the benefits of breastfeeding, with 97.5% strongly agreeing that breastfeeding helps mothers feel closer to their babies and 87.4% agreeing that breastfed babies get a better start in life. The positive perceptions of breastfeeding's emotional and developmental benefits align with several previous studies. For instance, Odom et al. [25] found that many mothers recognize the health benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and child, a sentiment echoed in this study where 87.4% of mothers believe breastfed babies get a better start in life [25]. Similarly, in a study conducted in a different region of Nigeria, Ekanem, et al. [7] reported that a high percentage of mothers were aware of the nutritional and bonding benefits of breastfeeding, paralleling the findings from Aluu where 97.5% of mothers felt closer to their babies through breastfeeding. Conversely, the concerns about physical appearance and freedom align with global and regional studies. For example, in a study conducted by Khasawneh and Khasawneh [26], concerns about breastfeeding impacting body image were prominent among nursing mothers. Additionally, a significant proportion of mothers in the Aluu study found public breastfeeding embarrassing (55.2% strongly disagreed that it is acceptable publicly), which is consistent with findings from other studies that highlight cultural and social barriers to public breastfeeding [15].

The mixed feelings about the social acceptance of breastfeeding in public underscore a complex cultural context. While 54.6% agreed that breastfeeding is acceptable publicly, a significant minority (22.7%) strongly disagreed. This dichotomy reflects the findings of previous research which indicates that while breastfeeding is often considered ideal, public breastfeeding remains controversial in many societies [2]. The perception of embarrassment and the social stigma attached to public breastfeeding can significantly hinder breastfeeding practices, as noted by Brown [27]. The study also highlights the dynamics of decision-making regarding breastfeeding, with nearly half (47.0%) strongly agreeing that both parents should make the decision, suggesting a shift towards shared parental responsibilities in child-rearing. This perspective is supported by studies like that of Arora et al. [13], which emphasize the role of paternal support in successful breastfeeding practices. A significant consensus was observed on the belief that women of all educational statuses (89.9%) and socio-economic classes (87.4%) should breastfeed their children. This reflects an understanding that breastfeeding transcends socio-economic barriers, an aspect supported by research indicating that educational interventions can effectively promote breastfeeding across different socio-economic groups [28].

Conclusion

While knowledge of breastfeeding practices among nursing mothers in Aluu community is relatively high, attitudes towards breastfeeding, especially in public and its aesthetic impact, remain largely negative. Targeted educational interventions are necessary to improve both knowledge and attitudes to support optimal breastfeeding practices.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Infant and young child feeding.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J., França, G. V., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., & Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017):475-490.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lessen, R., & Kavanagh, K. (2015). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Promoting and supporting breastfeeding. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115(3):444-449.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] & ICF. (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Agunbiade, O. M., & Ogunleye, O. V. (2012). Constraints to exclusive breastfeeding practice among breastfeeding mothers in Southwest Nigeria: Implications for scaling up. International Breastfeeding Journal, 7(1):1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Onah, S., Osuorah, D. I. C., Ebenebe, J., Ezejiofor, T., Ekwochi, U., & Ndukwu, I. (2014). Infant feeding practices and maternal socio-demographic factors that influence practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Nnewi South-East Nigeria: A cross-sectional and analytical study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 9(1):1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ekanem, L. A., Ekanem, A. P., Asuquo, A., & Eyo, V. O. (2012). Attitude of working mothers to exclusive breastfeeding in Calabar Municipality, Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Food Research, 1(2):71-75.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ekure, E. N., Antia-Obong, O. E., Udo, J. J., & Ekanem, E. E. (2013). Maternal perceptions of exclusive breastfeeding in Calabar, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics, 40(2):97-102.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sriraman, N. K., & Kellams, A. (2016). Breastfeeding: What are the barriers? Why women struggle to achieve their goals. Journal of Women's Health, 25(7):714-722.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Airaodion AI, Ijioma CE, Ejikem PI. (2023). Prevalence of Erectile Dysfunction in Men with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Osun State, Nigeria. Direct Res. J. Agric. Food Sci, 10:45-52.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jama, A., Gebreyesus, H., Wubayehu, T. Gebregyorgis, T., Teweldemedhin, M., Berhe, T. & Berhe, N. (2020). Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and its associated factors among children age 6-24 months in Burao district, Somaliland. Int Breastfeed J. 15:5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akadri, A., and Odelola, O. (2020). Breastfeeding Practices among Mothers in Southwest Nigeria. Ethiopian journal of health sciences, 30(5):697-706.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arora, S., McJunkin, C., Wehrer, J., & Kuhn, P. (2019). Major factors influencing breastfeeding rates: Mother's perception of father's attitude and milk supply. Pediatrics,106(5): E67.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kantorowska, A., Wei, J. C., Cohen, R. S., Lawrence, R. A., Gould, J. B., & Lee, H. C. (2016). Impact of education and socio-economic status on breastfeeding practices in the NICU. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(1):43-51.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sriram, S., Soni, P., Thanvi, R., Prajapati, N., & Mehariya, K. M. (2013). Knowledge, attitude and practices of mothers regarding infant feeding practices. National Journal of Community Medicine, 4(2):258-263.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Garcia, E., Timmermans, D. R., van Leeuwen, E., & Prins, J. M. (2020). The impact of housing quality on breastfeeding practices among mothers in low-income households. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(1):111-119.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Giglia, R. C., & Binns, C. W. (2006). Alcohol and lactation: A systematic review. Nutrition & Dietetics, 63(2):103-116.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chiodo, L. M., Delaney-Black, V., & Sokol, R. J. (2010). Alcohol and the breastfeeding mother. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 57(2):383-400.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Omotola, B. D., Adewumi, I. K., & Olumide, A. O. (2019). Breastfeeding practices and determinants among nursing mothers in Nigeria. African Health Sciences, 19(2):2053-2060.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Oche, M. O., Umar, A. S., & Ahmed, H. (2011). Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding in Kware, Nigeria. African Health Sciences, 11(3):518-523.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kimani-Murage, E. W., Madise, N. J., Fotso, J. C., Kyobutungi, C., Mutua, M. K., Gitau, T. M., & Yatich, N. (2011). Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in urban informal settlements, Nairobi Kenya. BMC Public Health, 11(1):396.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Otoo, G. E., Lartey, A. A., & Perez-Escamilla, R. (2009). Perceived incentives and barriers to exclusive breastfeeding among periurban Ghanaian women. Journal of Human Lactation, 25(1):34-41.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ajibade, B. L., Adelekan, A. L., & Salau, O. R. (2013). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. American Journal of Nursing Research, 1(1):20-24.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Karanja, N., Juma, P., Laserson, K. F., Njenga, M., Ng'ang'a, Z., & Sommer, A. (2017). Community perceptions of breastfeeding and infant nutrition among a sample of Kenyan women. BMC Public Health, 17(1):72.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Odom, E. C., Li, R., Scanlon, K. S., Perrine, C. G., & Grummer-Strawn, L. (2013). Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics, 131(3):e726-e732.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Khasawneh, W., & Khasawneh, A. (2017). Knowledge, attitude, motivation and planning of breastfeeding: A comparative analysis of breastfeeding mothers and non-breastfeeding mothers. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing, 35:37-44.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Brown, A. (2015). Breastfeeding Uncovered: Who Really Decides How We Feed Our Babies?. Pinter & Martin.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dennis, C. L. (2002). Breastfeeding initiation and duration: A 1990-2000 literature review. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 31(1):12-32.

Publisher | Google Scholor