Research Article

Iceberg Profile of Martial Arts and Combat Sports Practitioners During The SARS-Cov-2 Pandemic

- Jonatas Deivyson Reis da Silva Duarte 1,2*

- Michelle Jalousie Kommers 2

- Camila Pasa 3,4

- Matej Babic 5,6

- Arturo Alejandro Zavala 6,7

- Waléria Christiane Rezende Fett 1,8

- Carlos Alexandre Fett 1,2,8

1Metabolic, Sports and Health Research Team, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

2Faculty of Medicine and Health, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

3University of Cuiaba, Brazil.

4Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Split, Croatia.

5Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Zagreb, Croatia.

6Faculty of Economics, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

7Faculty of Statistics, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Peru.

8Faculty of Physical Education, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

*Corresponding Author: Jonatas Deivyson Reis da Silva Duarte, Metabolic, Sports and Health Research Team, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Citation: J.D.R.S. Duarte, Michelle J. Kommers, Pasa C, Babic M, Arturo A. Zavala, et al. (2025). Iceberg Profile of Martial Arts and Combat Sports Practitioners During The SARS-Cov-2 Pandemic, International Journal of Biomedical and Clinical Research, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(5):1-8. DOI: 10.59657/2997-6103.brs.25.065

Copyright: © 2025 Jonatas Deivyson Reis da Silva Duarte, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 28, 2025 | Accepted: April 01, 2025 | Published: April 10, 2025

Abstract

Introduction: The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had a negative impact on the mood of many people. It is known that the practice of martial arts is a way to improve mood.

Objective: To analyze and compare the mood of regular jiu-jitsu, kickboxing and muay thai (kick/muay) practitioners and non-sport practitioners of both genders during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study with three groups: 1) jiu-jitsu (n=45); 2) kick/muay (n=60) and 3) not practicing sports (n=43), totalizing a sample of one hundred and forty-eight volunteers. To analyze mood, the Brunel Mood Scale (BRUMS) was used. To compare the different groups the One-Way ANOVA test was used with the significance value of p<0.05.

Results: Tension, hostility, fatigue and confusion were higher in the non-sport practitioners’ group (p<0.05).

Conclusion: Jiu-jitsu and kick/muay practitioners had a good mood during the sars-cov-2 pandemic.

Keywords: sport psychology; mental health; psychiatry

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 emerged in China in late 2019 and has spread rapidly around the world, and has been declared a global public health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. Some of its symptoms may be fever and difficulty breathing, resembling the common cold [2]. Its transmission occurs from person to person, mainly through oro nasal secretion, which makes its containment difficult [2]. It was then, that in March 2020 the WHO declared a pandemic state, the main measures adopted were social isolation, hand hygiene, the use of face mask in public places, closing of non-essential services, among others [3]. Recent data states that by 2022 there will be over 546 million confirmed cases and over 6.3 million deaths worldwide [4]. As a consequence of this index, it has brought about in some people fear, anxiety, anguish, and even the aggravation of pre-existing psychiatric disorders [5]. In order to minimize contamination, there were decrees of social distancing in Brazil, which sanctioned the closure of gyms. With the reduction of hospitalization rates and deaths, in May 2020, there was a presidential decree that included gyms in the list of essential activities, providing the return of physical activities in these places [6]. In this sense, for So and Kwon [7] regular physical exercise is a way to promote health, well-being and strengthen the immune system, and can reduce the crises resulting from infection caused by SARS-CoV-2. Among the various manifestations of physical exercise, martial arts are some of them [8]. In martial arts there are several modalities with different characteristics and rules. James et al [9] differentiate martial arts into strike (kickboxing, taekwondo, muay thai, karate, boxing), grappling (judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu), and mixed martial arts.

Among the various modalities, jiu-jitsu, kickboxing and muay thai are world-renowned and widely practiced [10-13]. The jiu-jitsu is a martial art characterized by falls, strangulation and joint immobilization. Although it originated in Japan, the Gracie family from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, was responsible for promoting the martial art, giving rise to the nomenclature Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu [14]. As for kickboxing and muay thai, they are considered similar in that two fighters use variations of punches and kicks against each other for score or knockout [15], so much so that studies have unified the two modalities into a single group as if they were synonymous [16,17]. However, the two modalities contain some differences, since muay thai is of Thai origin [11] and the kickboxing of North American origin [18]. From the point of view of the rules in muay thai it is allowed elbows and knees continuously, however, in kickboxing it is not allowed elbows and specifically in the K1 modality it is not allowed knees continuously. In muay thai the athletes use rituals of presentation before the fight, but not in kickboxing. One aspect in common among the various martial arts is that they can be practiced by children, adults and elderly people in an appropriate and adapted way, and can also be used for health, self-defense and high-performance purposes [19].

Among the many benefits of practicing martial arts, besides physical conditioning [20], we highlight the improvement in mood. Studies with jiu-jitsu, kickboxing [21], tai chi chuan [22], taekwondo [23] and kung fu [24] confirm such statements. In the classical sport psychology literature, there is a theory called the iceberg profile, which is the high value of the positive variable vigor compared to the negative variables (tension, hostility, depression, fatigue and confusion) that in the line graph resembles an iceberg [25]. This type of marker indicates a good mood state that can also be linked to sports performance [26]. In contrast, the reverse iceberg profile is the higher score of tension, hostility, depression, fatigue, and confusion that is related to psychological health problems [27]. However, we note the absence of studies of this nature with martial artists during the pandemic. In this context, the pandemic changed the type of training that was previously used by martial artists, as they kept their training routines at home [28] and this had a negative impact on their mood [29]. Thus, the present study aimed to analyze and compare the mood state and iceberg profile of martial arts practitioners and physically inactive individuals.

Methods

Participants

This is a cross-sectional quantitative study, in which 148 volunteers selected by convenience (all volunteers who agreed to participate) participated, and were distributed into three groups: 1) jiu-jitsu (n = 45) with a mean age of twenty-nine years; 2) kick/muay with a mean age of twenty-eight years (n = 60), and 3) not practicing sports (n = 43) with a mean age of twenty-four years. When separated by gender the groups showed the following distribution: male jiu-jitsu (n = 23) with a mean age of thirty-two years, female jiu-jitsu (n = 22) with a mean age of twenty-seven years, male kick/muay (n = 36) with a mean age of twenty-eight years, female kick/muay (n = 24) with a mean age of twenty-eight, male non-sport practitioners (n = 20) with a mean age of twenty-five, and female non-sport practitioners (n = 23) with a mean age of twenty-four.

Procedures

First, the owners and teachers of the martial arts schools in the city of Cuiabá in the state of Mato Grosso in the Midwest region of Brazil were contacted to request authorization and clarification of the present study. Right after the authorization, the researchers approached the academy students just before the end of their respective classes to explain about the procedures, risks, objectives, and criteria for the participation in the study. After that, they wrote down the Whatsapp® number to send the questionnaire and the Informed Consent Form (via Google Forms). At all times the researchers followed biosafety procedures (use of face mask and alcohol gel on hands at all times). Other volunteers were invited via email and Instagram® via an explanatory /convocative text with the questionnaire link at the end. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT-no.3.102.414) and conducted by the Meta-bolic, Sports and Health Research Team Research Center of this institution (NP-TIMES UFMT). The data were collected from April to July 2021.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria adopted were not using anxiolytic, psychotropic, and antidepressant medications for all groups. For those who practiced martial arts, it was adopted the criterion of at least two months of continuous practice in the modality with a minimum of 75% attendance in the last month. For the group of non-sports practitioners, we included those who reported being at least two months without practicing physical exercises and were classified as sedentary or insufficiently active.

Assessment Instrument

To analyze mood state, the Brunel Mood Scale (BRUMS) questionnaire was used [30]. It has been validated for use with the Brazilian public [31]. The BRUMS contains twenty-four questions where answers are given on a 5-point Likert scale, where 0 is "not at all" and 4 is "very much”. The participant checked/checked the numbering that corresponded to the feeling at the time of the response. According to Behnke et al [32], the use of questionnaire in studies provide valid and reliable information. Table 1 presents the different BRUMS variables and their respective definitions.

Table 1: Definitions of mood variables.

| Variables | Definition |

| Tension | Increased Tension, Worry, Anxious and Impatient. |

| Depression | Sadness, Unhappiness, Depressed, Lonely and Down. |

| Hostility | Grumpy, Irritable, Bored and Nervous. |

| Fatigue | State of Tiredness, Exhausted and Without Energy. |

| Vigor | Animated, Active, Happy, Full of Good Mood and Energetic. |

| Confusion | Low Lucidity and Confusion. |

| Adapted from Faro Viana et al [33]. | |

Statistical Analysis

The normality of the data was analyzed by the Shapiro-Wilk test and the One-way ANOVA was used to compare the variables of the different groups and genders. For the non-parametric data, Spearman's correlation test was used to analyze the influence of depression with the other mood variables. The software used for the analyses was SPSS version 25. For all tests the significance value adopted was 5%, where (p lessthan 0.05).

Results

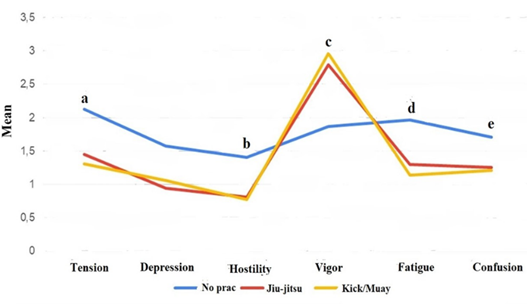

The mean age of the participants showed no statistical difference (p greaterthan 0.05), showing homogeneity in the sample. Groups 1 and 2 were classified as very active, while group 3 was classified as insufficiently active. Figure 1 shows the results of the comparisons between the different groups in this study - jiu-jitsu, kick/muay and non-sports practitioners during the pandemic. Only the jiu-jitsu and kick/muay groups had the iceberg profile. For the non-sport practitioners group the variables of tension, hostility, fatigue and confusion were significantly higher than the jiu-jitsu and kick/muay groups (p lessthan 0.05). In contrast, the vigor variable was significantly higher in the jiu-jitsu and kick/muay groups (p lessthan 0.05), showing a good mood state in the martial arts practicing groups.

Figure 1: Iceberg profile of jiu-jitsu and kick/muay practitioners and non-sport practitioners.

Note: kick/muay = kickboxing and muay thai; no prac = not practicing sports; a = significantly higher tension in the no prac group compared to jiu-jitsu and kick/muay (p lessthan 0.05); b = significantly higher hostility in the no prac group compared to jiu-jitsu and kick/muay (p lessthan 0.05); c = significantly higher vigor in the jiu-jitsu and kick/muay groups compared to no prac (p lessthan 0.05); d = significantly higher fatigue in the no prac group compared to jiu-jitsu and kick/muay (p lessthan 0.05); e = significantly higher confusion in the no prac group compared to jiu-jitsu and kick/muay (p lessthan 0.05).

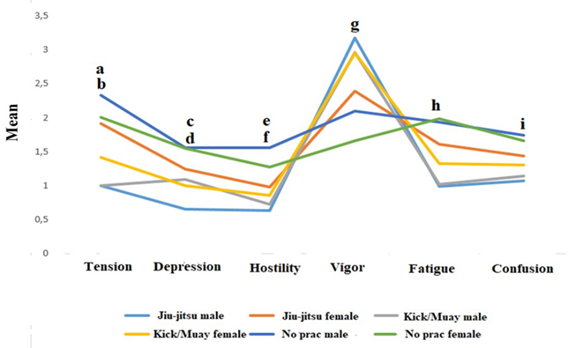

The Figure 2 describes the results of the comparisons between the different mood variables with respect to the genders, male jiu-jitsu, female jiu-jitsu, male kick/muay, female kick/muay, male non-sport practitioners and female non-sport practitioners. High tension values were observed in the female jiu-jitsu group compared to the male jiu-jitsu group (p lessthan 0.05). Still in the tension variable, the groups of non-practicing sports male and female was significantly higher when compared with male jiu-jitsu and male kick/muay (p lessthan 0.05). As for the depression variable among martial arts practitioners, there was a difference only in the female jiu-jitsu group, where it was higher than in the male jiu-jitsu and male kick/muay groups (p lessthan 0.05). For the non-practicing sports group of both genders, the depression variable was higher than in the male jiu-jitsu group (p lessthan 0.05). The non-practicing group had the hostility variable higher than the male jiu-jitsu and kick/muay groups (p lessthan 0.05). As for the non-practicing women, this same variable resulted higher only with the male kick/muay group (p lessthan 0.05). The positive variable vigor had no difference between the groups of martial arts practitioners (p greaterthan 0.05), however, the male jiu-jitsu, male kick/muay and female kick/muay groups had significantly higher vigor than the non-practicing sports male and female and the female jiu-jitsu group (p lessthan 0.05). However, the female jiu-jitsu group presented the iceberg profile, showing a good mood state (figure 2). The male martial arts practitioners (jiu-jitsu and kick/muay) had significantly lower perceived fatigue and confusion compared to the male and female non-athlete groups (p lessthan 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of mood variables and iceberg profile of male jiu-jitsu practitioners, female jiu-jitsu practitioners, kick/muay male, kick/muay female, non-practitioner’s male and non-practitioner’s female.

Note: kick/muay = kickboxing and muay thai; no prac = non-practitioners a = tension of jiu-jitsu female was significantly higher than that of jiu-jitsu male (p lessthan 0.05); b = tension of no prac male and no prac female was significantly higher than that of jiu-jitsu male and kick/muay male (p lessthan 0.05); c = depression of jiu-jitsu female was significantly greater than that of jiu-jitsu male and kick/muay male (p lessthan 0.05); d = depression of no prac male and no prac female was significantly greater than that of jiu-jitsu male (p 0.05); e = hostility of no prac male was significantly higher than that of jiu-jitsu male and the kick/muay male (p lessthan 0.05); f = hostility of no prac female was significantly higher than that of the kick/muay male (p lessthan 0.05); g = vigor of no prac male and no prac female was significantly lower than that of jiu-jitsu male, kick/muay male and the kick/muay female (p lessthan 0.05); h = fatigue of no prac male and no prac female was significantly greater than that of jiu-jitsu male and kick/muay male (p lessthan 0.05); i = confusion of no prac male and no prac female was significantly greater than that of jiu-jitsu male and kick/muay male (p lessthan 0.05).

Depression showed a strong positive correlation with tension, hostility, and confusion, and a moderate positive correlation with fatigue (p lessthan 0.05) (Table 2). On the other hand, there was a moderate negative correlation with the vigor variable (p lessthan 0.05). The data in table 2 indicate that depression can interfere with/increase the other negative mood variables (tension, hostility, fatigue, and confusion). However, with the positive variable (vigor) the opposite occurs.

Table 2: Spearman's correlation of depression and other mood variables.

| Tension | Hostility | Vigor | Fatigue | Confusion | |

| Depression | 0.7407a | 0.7324a | -0.6300a | 0.6531a | 0.7360a |

Note: a = p lessthan 0,05

Discussion

Our main findings were that practicing martial arts during the pandemic helped maintain good mood state compared to non-sports practitioners. Confirming our results, a recent study with the same modalities showed that men practicing martial arts had a better mood state compared to those not practicing sports before the pandemic period [21], resembling the present study. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to analyze the mood state of jiu-jitsu, kick/muay and non-sport practitioners of both genders during the pandemic. Previous studies have analyzed the impact of the pandemic on psychological health in different team and individual sports [29,34,35] and all of these studies showed a negative impact of the pandemic on the mental health of athletes. In our turn, this negative impact may have influenced the worsening of mood status in the female jiu-jitsu group when compared to the other groups of martial arts practitioners. Previous studies have shown that women practitioners of martial arts, when compared to men practitioners of the same modalities, tend to have worse mood state [36-38]. However, the positive mood (vigor) of the kick/muay female group resembled the kick/muay and jiu-jitsu male groups. Distinct from this, no similarity was found in the jiu-jitsu female group with the other groups, perhaps a possible explanation is because people reacted differently to the pandemic [39]. Another possible explanation why the vigor of the female jiu-jitsu group was lower than the other martial artist groups may be due to hormonal issues that can negatively impact the mood of women [36]. However, the female jiu-jitsu group was in the iceberg profile, which still indicates the contribution of its regular practice in psychological health. From a neurochemical point of view, good psychological health can be attributed to the production of serotonin, dopamine and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor [40,41].

Although we did not count the amount of training our volunteers did before and after the pandemic, the fact is that in this time interval the martial artists had good psychological health, resembling the study of Australian tennis players, who decreased their training hours during the pandemic but maintained their state of well-being [42]. Also resembling our findings, studies conducted before the pandemic, but with other sports such as running [43], the extreme conditioning training [44], the pilates [45], the yoga [46], the swimming [47], and resistance training [48], showed a positive impact on physical exercise and mental health. The findings of these different studies show that both aerobic and anaerobic exercises can be viable options for improving mental health, which would depend on the individual's preference. The iceberg profile can be found in results of studies developed with various sports, such as jiu-jitsu [49], basketball [50], bodybuilders [51], runners [52], gymnasts [53]. These findings are also in line with our results. However, future studies are needed to deepen the iceberg profile between different martial arts and combat sports. The depression variable had moderate to strong significant correlations with the other negative mood variables (tension, hostility, fatigue, and confusion). A study with karate athletes showed strong to very strong correlations (r = 0.76 to r = 0.85; p lessthan 0.05) between depression and the other negative mood variables [54]. These results are in line with our findings in that it correlates depression with tension, hostility, fatigue, and confusion. In this sense, these results confirm the statements of [55] in which depression is the most important negative mood variable, because it influences the intensity of the responses of the other negative variables. Thus, we can infer that the significant moderate negative correlation between vigor and depression shows the reliability of the answers given by the volunteers. For our part, we recognize that there are potential limitations to this study. The number of volunteers was relatively small, making it impossible for us to generalize the results, and the cross-sectional study methodology makes it impossible to identify incidence. In contrast, the present study demonstrates the actual data of the mood state of martial arts practitioners and non-sports practitioners during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Jiu-jitsu and kick/muay practitioners of both genders appeared to have better mood state compared to non-sport practitioners (physically inactive) during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Similarly, the martial arts practitioner groups achieved the iceberg profile, unlike the physically inactive group. In this sense, the increased vigor promoted by these sports seems to be a good mechanism for preventing/treating depression and consequently tension, hostility, fatigue and confusion.

Declarations

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the owners of the dojos (place where martial arts are practiced) for authorizing us to interview the students. We also thank everyone who agreed to participate as volunteers in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this study declare that there is no conflict of interest or sponsorship that may have influenced the results.

References

- Muralidar, S., Ambi, S. V., Sekaran, S., Krishnan, U. M. (2020). The Emergence of COVID-19 as a Global Pandemic: Understanding the Epidemiology, Immune Response and Potential Therapeutic Targets of SARS-CoV-2. Biochimie, 179:85-100.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rahman S, Montero MTV, Rowe K, Kirton R, Kunik F. (2021). Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentations, Diagnosis and Treatment of COVID-19: A Review of Current Evidence. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 14(5):601-621.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Güner, H. R., Hasanoglu, I., Aktas, F. (2020). COVID-19: Prevention and Control Measures in Community. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 50(9):571-577.

Publisher | Google Scholor - COVID, W. (2020). COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. Americas, 1(965):774.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sher, L. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Suicide Rates. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(10):707-712.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Brazil. Presidency of the Republic. General Secretariat. Decree No. 10,282 of March 20, 2020.

Publisher | Google Scholor - So, B., Kwon, K. H. (2022). The Impact of Physical Activity on Well-Being, Lifestyle and Health Promotion in an Era of COVID-19 and SARS-Cov-2 Variant. Postgraduate Medicine, 134(4):349-358.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wąsik, J., Wójcik, A. (2017). Health In the Context of Martial Arts Practice. Physical Activity Review, 5:91-94.

Publisher | Google Scholor - James, L. P., Haff, G. G., Kelly, V. G., Beckman, E. M. (2016). Towards A Determination of The Physiological Characteristics Distinguishing Successful Mixed Martial Arts Athletes: A Systematic Review of Combat Sport Literature. Sports Medicine, 46:1525-1551.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Silva, J. J. R., Del Vecchio, F. B., Picanço, L. M., Takito, M. Y., Franchini, E. (2011). Time-Motion Analysis in Muay-Thai and Kick-Boxing Amateur Matches. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 6(3):490-496.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saengsawang, P., Siladech, C., Laxanaphisuth, P. (2015). The History and Development of Muaythai Boran. Journal of Sports Science, 3(3):148-154.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Reis da Silva Duarte, J. D., Robalino Salinas, J. A., Fraga Souza, R. (2024). Kickboxing Scientific Production Indexed on PubMed: Productivity, Topics and Citations. Ido Movement for Culture: Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology, 24(3):23-31.

Publisher | Google Scholor - da Silva Duarte, J. D. R., Pasa, C., Kommers, M. J., de França Ferraz, A. (2021). Motivational Aspects of Male Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Kickboxing Practitioners. Brazilian Journal of Health Review, 4(3):12247-12256.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Scoggin III, J. F., Brusovanik, G., Izuka, B. H., Zandee van Rilland, E., Geling, O., et al. (2014). Assessment of Injuries During Brazilian Jiu-jitsu Competition. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 2(2):2325967114522184.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Buse, G. J., Santana, J. C. (2008). Conditioning Strategies for Competitive Kickboxing. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(4):42-48.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lystad, R. P., Strotmeyer, S. J. (2018). Concussion Knowledge, Attitudes and Reporting Intention Among Adult Competitive Muay Thai Kickboxing Athletes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Injury Epidemiology, 5:1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Herrera-Valenzuela, T., Vargas, JJ.N., Merlo, R., Valdés-Badilla, P. A., Pardo-Tamayo, C., et al. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 quarantine on body mass among combat sports athletes. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 37(6):1186-1189.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Machado, S., Souza, R. A., Simão, A., Jerônimo, D., Silva, N., et al. (2009). Comparative Study of Isokinetic Variables of The Knee in Taekwondo and Kickboxing Athletes. Fitness & Performance Journal, 8(6):407-411.

Publisher | Google Scholor - da Silva Duarte, J. D. R., Rodrigues, H. H. N. P., Cunha, M. G., de Macedo, A. F., Salinas, J. A. R. (2021). Dietary Intake in Kickboxing Fighters. Brazilian Journal of Development, 7(4), 42409-42424.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Duarte JDR da S, Ferraz ADF. (2022). Studies on Martial Arts, Fights and Sports Combat with Police: A Systematic Review. Sci Electron Arch. 15(3):77-83.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Da Silva Duarte JDR, Pasa C, Kommers MJ, Ferraz A de F, Hongyu K, et al. (2022). Mood Profile of Regular Combat Sports Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Phys Educ Sport. 22(5):1206-1213.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jimenez, P. J., Melendez, A., Albers, U. (2012). Psychological Effects of Tai Chi Chuan. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(2), 460-467.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bae, J. Y., Roh, H. T. (2021). Regular Taekwondo Training Affects Mood State and Sociality but Not Cognitive Function Among International Students in South Korea. Healthcare. 9(7):820.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Szabolcs, Z., Csala, B., Szabo, A., Köteles, F. (2023). Psychological Aspects of Three Movement Forms of Eastern Origin: A Comparative Study of Aikido, Judo and Yoga. Annals of Leisure Research, 26(1):44-64.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Morgan, W. P., Brown, D. R., Raglin, J. S., O'connor, P. J., Ellickson, K. A. (1987). Psychological Monitoring of Overtraining and Staleness. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 21(3):107-114.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lochbaum, M., Zanatta, T., Kirschling, D., May, E. (2021). The Profile of Moods States and Athletic Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Published Studies. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(1):50-70.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Terry, P. C., Parsons-Smith, R. L., Terry, V. R. (2020). Mood Responses Associated with COVID-19 Restrictions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11:589598.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Herrera-Valenzuela, T., Valdés-Badilla, P., Franchini, E. (2020). High-intensity interval training recommendations for combat sports athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista de Artes Marciales Asiáticas, 15(1):1-3.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Roberts, R. J., Lane, A. M. (2021). Mood Responses and Regulation Strategies Used During COVID-19 Among Boxers and Coaches. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:624119.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rohlfs, I. C. P. M., Rotta, T. M., Andrade, A., Terry, P. C., Krebs, R. J., et al. (2005). The Brunel of Mood Scale (BRUMS): Instrument for Detection of Modified Mood States in Adolescents and Adults’ Athletes and Non-Athletes. Fiep Bulletin, 75:281-284.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rohlfs, ICPDM, Rotta, TM, Luft, CDB, Andrade, A., Krebs, RJ, et al. (2008). Brunel Mood Scale (BRUMS): An Instrument for Early Detection of Overtraining Syndrome. Brazilian Journal of Sports Medicine, 14(3):176-181.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Behnke, M., Tomczak, M., Kaczmarek, L. D., Komar, M., Gracz, J. (2019). The Sport Mental Training Questionnaire: Development and Validation. Current Psychology, 38:504-516.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Viana, M. F., Almeida, P., Santos, R. C. (2001). Adaptation Into Portuguese of The Reduced Version of The Profile of Mood States-POMS. Análise Psicológica, 19(1):77-92.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mehrsafar, A. H., Moghadam Zadeh, A., Gazerani, P., Jaenes Sanchez, J. C., Nejat, M., et al. (2021). Mental Health Status, Life Satisfaction, And Mood State of Elite Athletes During The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Follow-Up Study in The Phases of Home Confinement, Reopening, And Semi-Lockdown Condition. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:630414.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lorenzo Calvo, J., Granado-Peinado, M., De la Rubia, A., Muriarte, D., Lorenzo, A., et al. (2021). Psychological States and Training Habits During The COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown in Spanish Basketball Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17):9025.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kuehner, C. (2017). Why is Depression More Common Among Women Than Among Men? The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2):146-158.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alsharawy, A., Spoon, R., Smith, A., Ball, S. (2021). Gender Differences in Fear and Risk Perception During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:689467.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fernández, M. M., Brito, C. J., Miarka, B., Díaz-de-Durana, A. L. (2020). Anxiety and Emotional Intelligence: Comparisons Between Combat Sports, Gender and Levels Using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale and The Inventory of Situations and Anxiety Response. Frontiers in Psychology, 11:130.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Preti, E., Di Pierro, R., Fanti, E., Madeddu, F., Calati, R. (2020). Personality Disorders in Time of Pandemic. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22:1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Da Silva Duarte JDR, Barros EA, Babic M. (2023). The Effect of Martial Arts on the Production of Mood Regulating Neurotransmitters: Point of View. Addict Res Behav Ther. 1(2):1-5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - da Silva Duarte, J. D. R. (2023). Physical Exercise, Psychological and Neurological Health: Reviewing the Anxiety and Depression Variables. J Clin Psychol Ment Heal. 2(1):1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Turner, M., Beranek, P., Rogers, S. L., Nosaka, K., Girard, O., et al. (2021). Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mood and Training in Australian Community Tennis Players. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3:589617.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Oswald, F., Campbell, J., Williamson, C., Richards, J., Kelly, P. (2020). A Scoping Review of The Relationship Between Running and Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21):8059.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pereira, E. S., Krause, W., Calefi, A. S., Georgetti, M., Guerreiro, L., et al. (2019). Extreme Conditioning Training: Acute Effects on Mood State. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 25(2):137-141.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fleming, K. M., Campbell, M., Herring, M. P. (2020). Acute Effects of Pilates on Mood States Among Young Adult Males. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 49:102313.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tanaka, A., Tokuda, N., Ichihara, K. (2018). Psychological and Physiological Effects of Laughter Yoga Sessions in Japan: A Pilot Study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 20(3):304-312.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Massey, H., Kandala, N., Davis, C., Harper, M., Gorczynski, P., et al. (2020). Mood And Well-Being of Novice Open Water Swimmers and Controls During an Introductory Outdoor Swimming Programme: A Feasibility Study. Lifestyle Medicine, 1(2):e12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Collins, H., Booth, J. N., Duncan, A., Fawkner, S. (2019). The Effect of Resistance Training Interventions on Fundamental Movement Skills in Youth: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine-Open, 5:1-16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Andrade, A., Silva, R. B., Flores Junior, M. A., Rosa, C. B., Dominski, F. H. (2019). Changes in Mood States of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Athletes During Training and Competition. Sport Sciences for Health, 15:469-475.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Silva, J. C., Aniceto, R. R., Oliota-Ribeiro, L. S., Neto, G. R., Leandro, L. S., et al. (2018). Mood Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Exercise Among Basketball Players. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 125(4):788-801.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Newton, L. E., Hunter, G., Bammon, M., Roney, R. (1993). Changes in Psychological State and Self-Reported Diet During Various Phases of Training in Competitive Bodybuilders. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 7(3):153-158.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gula, J. N., Mattes, V. V., Paludo, A. C., da Silva, M. P., Tartaruga, M. P. (2019). Motivational Profile and Mood State in Street Runners Participating in Running Groups. ConScientiae Saúde, 18(4):444-454.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Verardi, C. E. L., Hirota, V. B., Rinaldi, I. M., Battaglini-Mattos, M. P., Luciano, A. R. M. B., et al. (2018). Athlete’s Mood State Before Artistic Gymnastics Competitions. Psychology, 9(14):2859-2868.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wong, R. S., Thung, J. S., Pieter, W. (2006). Mood and Performance in Young Malaysian Karateka. Journal Of Sports Science & Medicine, 5(CSSI):54.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lane, A. M., Terry, P. C. (2000). The Nature of Mood: Development of A Conceptual Model with A Focus on Depression. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 12(1):16-33.

Publisher | Google Scholor