Clinical Image

How to Identify a Retained Wound Drainage Device in Complementary Imaging Tests

- Marta Román Garrido 1*

1Primary care Department, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain.

*Corresponding Author: Marta Román Garrido, Primary care Department, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain.

Citation: P A G Ruiz, Marta R Garrido. (2024). How to Identify a Retained Wound Drainage Device in Complementary Imaging Tests, Clinical Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 2(3):1-4. DOI: 10.59657/2995-6064.brs.24.019

Copyright: © 2024 Patricia Alejandra Garrido Ruiz, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: December 04, 2023 | Accepted: December 21, 2023 | Published: February 08, 2024

Abstract

Retained surgical drains are a rare, yet preventable occurrence that can lead to serious consequences. In this report, we discuss a case from our institution to exemplify the difficult management of this issue, as well as provide an overview of techniques for preventing and removing retained drains based on current literature.

Keywords: retained; surgical; drainage; complication; device

Introduction

Retained surgical drains, though rare, remain a preventable complication reported in the literature. This issue commonly arises due to improper suturing of the drain during wound closure or drain breakage. The purpose of this review is to educate surgical teams on techniques for avoiding retained drains and removing them without additional surgery.

Discussion

Several techniques exist for preventing, confirming, and managing retained surgical drains. Based on traditional surgical education, the principal technique involves cutting the drain between drain holes, which is a near-universal practice. If the perforations were to fail, the drain would break at the weakest point. This could indicate that a portion is still retained upon removal. It is recommended to cut the drain purposely to ensure a consistent number of holes each time. Count the number of holes during removal to ensure no fragments are retained. It is important to document the number of drain holes in surgeries where the wound size and the number of drain holes are consistent. In cases where the length of the drain varies, it is crucial to confirm the number of holes in the drain during removal and to record it in the dictation.

There are several techniques that can be used for prevention. The first technique involves keeping some slack in the drain so that the black dot (or another marker that indicates the appropriate skin level) is hidden below the skin after closing the wound. Then, gently pull the slack out until the marker reaches the skin surface. If it moves smoothly, it is unlikely to have been sutured-in. After inserting the trocar, it is recommended to keep the end of the drain long and protruding by about 2-3 cm from the distal end of the wound. Once the fascial closure is done, pull the proximal aspect (trocar end) until the protruding end slides under the closed layer. If you encounter any resistance, it indicates that the drain is tethered. After closing the layer above a drain, a hemostat can be placed on the free end to evaluate for any resistance by sliding it back and forth before proceeding with the closure. This technique is known to be effective in ensuring proper closure and avoiding any complications [1]. If a firm pull fails during routine drain removal, there are other techniques that the surgeon may use to remove it. These techniques should be used at the surgeon's discretion and depending on the patient's tolerance. If there is a concern that a part of the drain may have broken off within the wound, radiographs should be taken to confirm this as most drains have slight radiopacity.

Figure 1: Lateral x-ray of intramuscular retained drain level L2-L5. The drainage device can be identified because of its radiopacity marked by the blue arrows pointing towards its endings.

Another technique is to use two hemostats to gently apply traction and clamp the drain as far as possible. Gentle traction is needed to apply with the second clamp, alternating with the first hemostat until the suture is reached and cut. If the suture is deeper than 7 cm, this technique is unlikely to be effective. In cases where the drain breaks, it is recommended to use image intensification to advance a long, slender hemostat along the drain tract and grasp the retained drain [2]. It has been described that an appropriately sized Steinmann pin can be inserted into the drain lumen to cut the suture holding the drain in place. By placing the suture within the drain lumen, the surrounding soft tissues are protected and the suture can be cut from within. [3]

When removing silicone drains, which are softer than polyvinyl chloride (PVC) drains commonly used in Hemovac drains, surgeons should clamp the tubing and apply gentle traction while twisting the drain five to seven times. This technique will safely free the drain from the suture [4]. A technique has been described in the cardiovascular literature for removing a retained drain using an angioplasty balloon catheter. The catheter is inserted along the drain tract and into the retained drain lumen under image intensification. The balloon is then inflated within the drain lumen to create an interference fit. Once this is achieved, the retained drain can be extracted by pulling out the angioplasty balloon catheter [5]. If the patient still has the retained drain after attempting other techniques, they may need to undergo another surgery to remove it under general anesthesia.

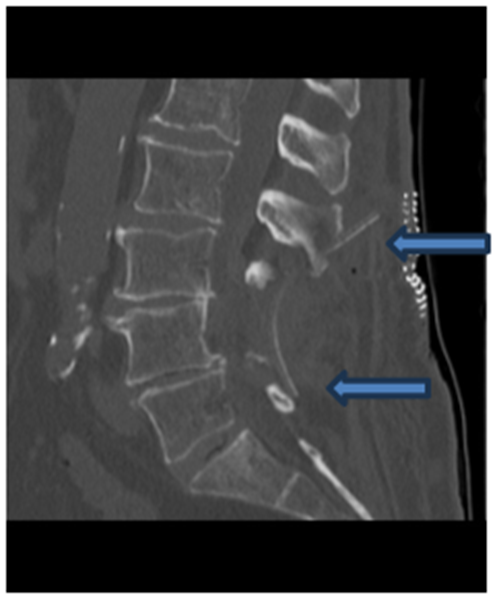

Figure 2: Sagittal CT of intramuscular retained drain level L2-L5. The drainage device can be identified because of its radiodensity marked by the blue arrows pointing towards its endings.

Figure 3: Sagittal bone window CT of intramuscular retained drain level L2-L5. The drainage device can be identified because of its radiodensity marked by the blue arrows pointing towards its endings.

The literature on general surgery reports various complications related to retained drains, including the development of abdominal fistulas, abscesses, and intestinal obstructions. In orthopedics, priority is placed on removing drains from joints to minimize infection risk, cartilage damage and range of motion restrictions. In neurosurgery, they are placed 24-48 hours to avoid blood accumulation in the surgical field.

As drain removals are rare occurrences, there are currently no controlled studies available on the subject. Zeide and Robbins [6] reported seven cases of retained drains: three were removed under conscious sedation, and four were left in situ. At the time of publication, no complications resulted from the drains left in situ. Gausden et al. [7] reviewed seven cases of retained drains after lumbar spine surgery over an 18-year period. Five were surgically removed while two remained in place without issues after 2 years. According to the authors, the production of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) drains can result in the release of vinyl chloride, which has been associated with the development of angiosarcoma in rats and factory workers. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this release occurs in relation to retained drains. There is insufficient evidence to recommend removing retained drains unless there is a specific problem such as limited range of motion. Although is common sense that as a general rule, foreign bodies should be removed since they are not a natural part of the body.

Conclusions

Retained surgical drains are a preventable complication. Consistent use of preventative techniques significantly reduces avoidable complications. Our recommendation is to remove the item if it has been accidentally retained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maury A., Southgate C., John A. (2003). A simple technique to avoid inadvertent deep anchorage of surgical drains. Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 85.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hak D. J. (2000). Retained broken wound drains: a preventable complication. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 14(3):212-213.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Redman J. F., Welch L. T, Bissada N. K. (1975). Technique for removing entrapped penrose drains. Urology.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lazarides S., Hussain A., Zafiropoulous G. (2003). Removal of surgically entangled drain: a new original non-operative technique. International Journal of Current Medical Science Practice, 10(1):63-64.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Namyslowski J., Halin N. J., Greenfield A. J. (1996). Percutaneous retrieval of a retained Jackson-Pratt drain fragment. CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology, 19(6):446-448.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zeide M. S., Robbins H. (1975). Retained wound suction-drain fragment. Report of 7 cases. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases, 36(2):163-169.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gausden E. B., Sama A. A., Taher F., Pumberger M., Cammisa F. P., Hughes A. P. (2015). Long-term sequelae of patients with retained drains in spine surgery. Journal of Spinal Disorders and Techniques, 28(1):37-39.

Publisher | Google Scholor