Case Report

Gallbladder Agenesis

- Lada Paul Eduardo 1*

- Sánchez Martin 2

- Martínez Peluaga Julián 2

- Caballero Fabián 2

- Casares Gonzalo 2

- Rojas Alejandra 3

- Molina Selene 3

- Matcoski Florencia 3

- Mazzei Fernando 3

1Head of the Surgery Service and Professor of General Surgery "Pablo Luis Mirizzi" Room 3/5. National Hospital of Clinics. UNC. Córdoba. Argentina.

2Assistant Professor of General Surgery "Pablo Luis Mirizzi". Room 3/5. National Hospital of Clinics. UNC. Córdoba. Argentina.

3General Surgery Resident "Pablo Luis Mirizzi". Room 3/5. National Hospital of Clinics. UNC. Córdoba. Argentina.

*Corresponding Author: Lada Paul Eduardo, Head of the Surgery Service and Professor of General Surgery

Citation: Lada P. Eduardo, Martin S, Martínez P. Julián, Fabián C, Gonzalo C, et al. (2024). Gallbladder Agenesis, Clinical Case Reports and Studies, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 6(2):1-5. DOI: 10.59657/2837-2565.brs.24.142

Copyright: © 2024 Lada Paul Eduardo, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: May 31, 2024 | Accepted: June 17, 2024 | Published: June 29, 2024

Abstract

Gallbladder agenesis (GA) is a rare congenital entity. Most patients remain asymptomatic, while those with symptoms report symptoms that mimic bile colic. Initial evaluation for suspected gallbladder pathology, such as ultrasound of the right upper quadrant, May be misleading or inconclusive. As a result, some patients are eventually diagnosed intra-operatively. Therefore, GA should be maintained as a differential diagnosis and should be performed as magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRI) when other tests are inconclusive. We present a 39-year-old woman who has chronic symptoms compatible with biliary colic and an equivocal ultrasound reported as sclera atrophic with cholelitiasis. Laparoscopy was performed during which the absence of gallbladder was found. Postoperative MRCP confirmed the diagnosis of GA.

Keywords: gallbladder agenesis; magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography; laparoscopy

Introduction

Gallbladder agenesis (GA) is a rare pathology. It is defined as the congenital absence of the gallbladder, associated or not with the absence of the cystic duct [1]. It is a rare congenital condition of the biliary system, where approximately 400 cases of (GA), both in autopsies and as clinical presentations, have been described in the literature [2]. On the other hand, more than 50% of cases are isolated and asymptomatic. These asymptomatic patients are mainly healthy and do not need interventions. However, some patients develop symptoms, presenting with clinical signs similar to the symptoms of gallbladder lithiasis. Symptoms commonly occur in the fourth or fifth decade of the patient's life [3].

Case Presentation

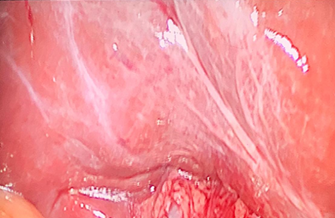

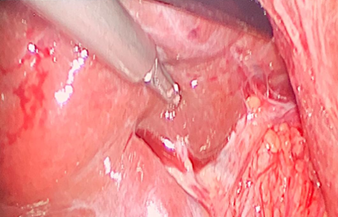

A 39-year-old female patient, referred from the Nephrology Department, with a history of chronic renal failure, without hemodialysis but likely to undergo a kidney transplant. The patient states that about 1 year ago she began with epigastric pain with irradiation to the HD, accompanied by abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting. On the other hand, on some occasions he manifested acidity and epigastric burning. He consulted the Gastroenterology Service where an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was carried out that showed normal esophagus, an antral region where multiple biopsies were performed and that showed according to the anatomic pathological result an antral gastritis. Helicobacter pylori negative. He was medicated with pump inhibitors, diet. At the same time, an ultrasound of the abdomen showed a decreased size and sclera atrophic Gallbladder. It improved her symptoms and then at 6 months, she started with abdominal pain. New ultrasound of the abdomen reveals a decreased gallbladder and sclera atrophic. Diet was indicated, where it evolved favorably. 1 month ago, new intense pain in the same region of right upper abdominal, accompanied by vomiting and nausea after ingestion. It was decided to consult the Surgery Department, where a new ultrasound of the abdomen was carried out, which showed sclera atrophic gallbladder with lithiasis. New upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which was normal. Faced with this situation and the repeated crises of abdominal pain, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy is proposed. In the laparoscopic examination, after the placement of the trocars, the Gallbladder (G) was not found in the region of the hepatic bed (FIGURE 1), it was explored on the left hepatic side where the Gallbladder was not found either. It was decided to explore the region of the main bile duct where a sclera atrophic organ could be found in this region by placing a clamp (FIGURE 2).

Figure 1: Laparoscopic examination. The gallbladder is not seen.

Figure 2: It is separated with forceps over the CBD. But no gallbladder is found.

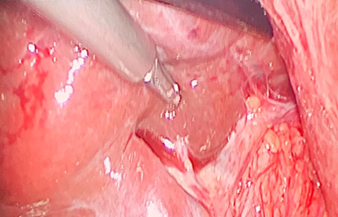

In addition, the sulcus of Rouviers is well observed, where common bile duct free of the vesicular organ is observed, allowing exploration of the confluent of the liverworts where gallbladder does not appear (FIGURE 3).

Figure 3: Sulcus de Rouviers can be observed. CBD and confluent are observed without G.

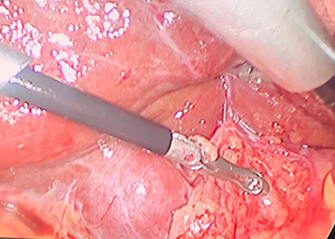

Finally, it was decided to release the Common Bile Duct (CBD) observe if there was a negative gallbladder outline (FIGURE 4). Finally, it was decided to finish the laparoscopic examination. Postoperative good evolution. 12-hour hospitalization. A MRCP was requested a week after surgery, the result of which was normal, but the gallbladder was not demonstrated. The patient was referred to the Nephrology Department. Finally, it was decided to release the VBP, to observe if there is a stub of gallbladder, which is negative (FIGURE 4).

Figure 4: Fat tissue is removed from CBD. Gallbladder was not found.

Discussion

The biliary system has relatively common abnormalities. The gallbladder is subject to these anomalies in number, location, and morphology. GA without extra hepatic biliary atresia is a well-recognized but extremely rare congenital anomaly in which G does not develop and is subsequently not found at the usual or most common atypical sites [4,5]. The first case was described by Lemery in 1701 [6]. From an epidemiological point of view, the incidence based on autopsy results is approximately one case per 6334 live births [5], or approximately 0.035 to 0.3% [7,8]. Allan S et al. [9] observed three cases of GA in 2451 cholecystectomies. Conversely, Jain et al. [10] reported four cases among 771 patients who underwent surgery for bile duct disease over a 5-year period. From the point of view of the embryology and etiology of GA, its congenital malformation, which may or may not be accompanied by cystic duct agenesis, is accepted [11]. It is accepted that embryogenesis is corroborated by the frequent association of agenesis with congenital malformations [1]. Another form is the existence of families in which this pathology has occurred in several members, suggesting that there are familial hereditary forms of AGV [12]. This abnormality may also be associated with other biliary and/or extra-biliary anomalies, such as unusual complications caused by common bile duct cysts [13,14].

Children with GA and distant malformations tend to have trisomy 13 or another chromosomal abnormality that carries a poor prognosis [8]. In this context, some authors [6,15] established a classification that can distinguish three groups: 1.- Fetal anomalies (12.9%): Patients who die in the prenatal period from other malformations, such as cardiovascular, genitourinary systems and gastrointestinal tract, but GA is observed at autopsy. 2.- Asymptomatic group (31.6%): These patients do not present biliary symptoms and GA are discovered during an autopsy or in surgery for another pathology. 3.- Symptomatic group (55.6%): These patients are between 40 and 50 years old, who do not have another congenital anomaly. Regarding the clinical symptoms of these symptomatic patients, abdominal pain is in most cases (90%), nausea and vomiting (66%), intolerance to CCK (37%), dyspepsia (30%) [6,16]. The symptoms presented by our patient, with abdominal pain, nausea, dyspepsia, similar to those described in the literature. Jaundice is very rare and may be associated with CBD lithiasis with or without cholangitis [10,17]. In addition, the examination may show pain on palpation of the abdominal upper right. Richards et al. [18], reviewed 44 cases of GA and found that dyspepsia was the predominant symptom in 15 of 44 patients (34%); 24 of 44 (54%) had symptoms suggestive of biliary colic and 12 of 44 (27%) had jaundice. Common duct stones were found in eight of 12 patients with jaundice, but not in any others.

Symptoms may be secondary to concomitant pathologies, such as primary duct stones and biliary dyskinesia, or may be related to non-biliary causes such as esophagitis and duodenitis [6,16,19,20). In GA, the hepatic bile duct can replace the absent gallbladder by dilating and taking over the function of bile storage [5]. The presence of biliary tract dyskinesia, increased resting pressure of the sphincter of Oddi, cholestasis, or infection of the bile ducts may initiate the onset of biliary symptoms and/or the formation of common bile duct stones, especially when two or more of these events occur in association [5,8,21]. In our case, the patient underwent two upper gastrointestinal endoscopies, where it was shown in one antral gastritis and in another that it was normal. Regarding the diagnosis, abdominal ultrasound is the initial examination, for the exploration of the biliary pathology. Its sensitivity is 95% in the diagnosis of gallstones [22]. Preoperative diagnosis of GA has been considered extremely difficult, and almost all diagnoses in symptomatic patients are made at laparotomy or during attempted laparoscopic cholecystectomy [17]. Although ideally, diagnosis should be made prior to surgery, this has been documented in only a few reports [23,24]. This is mainly due to the fact that radiological research methods for biliary pathology diseases have a sensitivity of <100>

Non-visualization of Gallbladder by ultrasound can be confirmed by preoperative hepatobiliary scintigraphy, abdominal CT, ERCP, or MRCP [16,23,27]. A preoperative diagnosis based on a CT scan, a HIDA scan, and a cautious ultrasound in twins would have been reported [28]. CT scan of the abdomen in nine patients with GA can accurately determine the condition before operation [29]. These authors suggested that an abdominal CT scan should be performed in any case in which gallbladder is not visualized on ultrasound. Orlando et al. [23], suggested that diagnostic confirmation is achieved by MRCP, thus avoiding laparotomy, whereas conventional hepatobiliary imaging studies and laparoscopy could not achieve a definitive diagnosis.

Conclusion

Finally, we believe that it is difficult to suspect this congenital malformation and even with studies such as ultrasound where it is a dependent operator. However, we should be suspicious of a diagnosis of gallbladder that is sclera atrophic and/or not visualized by this method. In this eventuality, CT of the abdomen and even more so the MRCP will make us consider the diagnosis of this GA, avoiding an exploratory laparotomy or exploratory laparoscopy as happened in our patient. Surgery can be risky in these patients because unnecessary dissection while looking for the non-existent gallbladder can result in injury to the biliary tree, hepatic vascular tree, or small intestine.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chouchaine A, Fodha M, Taha Abdelkefi M, Helali K, et al. (2017). Agénésie de la vésicule biliaire: à propos de trois caso. Pan Afr. Me.d J. 28:114-121.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Flores-Valencia JG, Vital-Miranda SN, Mondragón-Romano SP, de la Garza-Salinas LH. (2012). Agenesia vesicular: reporte de caso. Rev. Med. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 50(1):63-66.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Takano Y, Hoshino M, Iriyama S, Takayanagi K, Ishiro M, et al. (2018). Gallbladder agenesis with hepatic impairment: a case report. BMC Pediatrics. 18:360-363.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bennion RS, Thompson JE (Jr), Tompkins RK. (1988). Agenesis of the ball bladder without extrahepatic biliary atresia. Arch. Surg. 123:1257-1260.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jackson RJ, McClellan D. (1989). Agenesis of the gallbladder: a cause of false - positive ultrasonography. Am. Surg. 55:36-40.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Baltazar U, Dunn J, Gonzalez, Diaz S, Browder W. (2000). Agenesis of the gallbladder. South. Med. J. 93:914-915.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Waisberg J, Pinto PE Jr, Gusson PR, Fasano PR, Godoy AC. (2002). Agenesis of the gallbladder and cystic duct. Sao Paulo Med. J. 120:192-194.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bani-Hani K. (2005). Agenesis of the gallbladder: Difficulties in management. Review J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20:671-675.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Allan S, Hurrell TA. (1974). Agenesis of the gallbladder and cystic duct: A report of 3 cases. Br. J. Surg. 61:145-146.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jain BK, Das DN, Singh RK, Kukreti R, Dargan P. (2001). Agenesis of gallbladder in symptomatic patients. Trop. Gastroenterol. 22:80-82.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cabajo Caballero MA, Martin del Olmo JC, Blanco Alvarez JI, Atienza Sanchez R. (1997). Gallbladder and cystic duct absence: An infrequent malformation in laparoscopic surgery. Surg. Endosc. 11:483-484.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wilson JE, Deitrick JE. (1986). Agenesis of the gallbladder: Case report and familial investigation. Surgery. 99:106-109.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tabibian JH, Tabibian N, Aguet JC. (2009). Complications presenting as duodenal obstruction in an 82-year-old patient with gallbladder agenesis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 54:184-187.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bedi N, Bond-smith G, Kumar S, Hutchins R. (2013). Gallbladder agenesis with choledochal cyst: A rare association: a case report and review of possible genetic or embryological links. BMJ: Case Reports.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh B, Satyapal K S, Moodley J, Haffejee AA. (1999). Congenital absence of the gall bladder. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 21(3):221-224.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vijay KT, Kocher HH, Koti RS, Bapat RD. (1996). Agenesis of gall bladder: a diagnostic dilemma. J. Postgrad. Med. 42:80-82.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Belli G, D’Agostino A, Iannelli A, Rotondano G, Ceccarelli P. (1997). Isolated agenesis of the gallbladder. An intraoperative problem. Minerva. Chir. 52:1119-1121.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Richards RJ, Taubin H, Wasson D. (1993). Agenesis of the gallbladder in symptomatic adults: A case and review of the literature. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 16:231-233.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bekele Z. (2002). Congenital absence of the gallbladder and the cystic duct. Ethiop. Med. J. 40:171-178.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Galli A, Della Porta M, Rebuffat C. (2003). Laparoscopic diagnosis of gallbladder agenesis: Clinical case. Chir. Ital. 55:295-298.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fisichella PM, Di Stefano A, Di Carlo I, La Greca G, Russello D, et al. (2002). Isolated agenesis of the gallbladder: report of a case. Surg. Today. 32:78-80.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elorza-Orúe JL. (2001). Agenesia de la vesícula biliar: Presentación de un caso estudiado por RM-colangiografía. Cir Esp. 69(4):427-428.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Orlando R, Candiani F, Lirussi F. (2001). Agenesis of the gallbladder associated with Gilbert's syndrome. Surg. Endosc. 15 (7):757-759.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Azmat N, Francis KR, Mandava N, Pizzi WF. (1993). Agenesis of the gallbladder revisited laparoscopically. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 88:1269-1270.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kabiri H, Domingo OH, Tzarnas CD. (2006). Agenesis of the gall-bladder. Curr. Surg. 63(2):104-106.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chowbey PK, Dey A, Khullar R, Sharma A, Soni V, et al. (2009). Agenesis of gallbladder: our experience and a review of literature. Indian. J. Surg. 71(4):188-192.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Aspevik RK, Hjelseth B, Irtun O. (2002). Agenesis of the gallbladder. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 122:2774-2776.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sugrue M, Gani J, Sarre R, Watts J. (1991). Ectopia and agenesis of the gall‐bladder: a report of two sets of twins and review of the literature. Aust. N.Z. J. Surg. 61:816-818.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cho CH, Suh KW, Min JS, Kim CK. (1992). Congenital absence of gallbladder. Yonsei. Med. J. 33:364-367.

Publisher | Google Scholor