Research Article

First Trimester Missed Miscarriages and Medical Management: A Single Centre Descriptive Study

Post graduate institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

*Corresponding Author: Sanjaya Walawe Nayaka, Post graduate institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Citation: Walawe Nayaka S. (2025). First Trimester Missed Miscarriages and Medical Management: a Single Centre Descriptive Study, Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia publishers. 5(4):1-9. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.25.091

Copyright: © 2025 Sanjaya Walawe Nayaka, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 25, 2025 | Accepted: March 15, 2025 | Published: March 21, 2025

Abstract

Introduction: First trimester missed miscarriage is a relatively common situation among pregnant women. Three basic management options for this are expectant, medical and surgical. Medical management with Misoprostol is a safe and effective way out of these three methods.

Objectives: Aim is to describe the demographic, obstetrics and radiological factors associated with managing first trimester missed miscarriage with Misoprostol.

Method- Single centre descriptive study was conducted in a Teaching Hospital in Sri Lanka. Medically managed first trimester missed miscarriage (<12 weeks) were selected. Data retrieval was done using the bed head tickets. SPSS software was used to analyse the data.

Results: 167 women were recruited for the analysis. Overall success rate of vaginal Misoprostol was 62.3%.

Conclusion: This study provides an important overview of the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients treated for first trimester missed miscarriage in our institution.

Keywords: early pregnancy loss; miscarriages; misoprostol

Introduction

Background

Loss of the pregnancy within first 12 weeks is considered as early pregnancy loss or failure [1]. If this is diagnosed before passing products of conception, condition is called as missed miscarriage. This is a common entity in daily Obstetrics and Gynaecology practice. One in four women will encounter this during their life time [2]. Half of the spontaneous miscarriages are due to abnormalities of the chromosomes in the conceptus [3]. first trimester missed miscarriage leads to significant amount of social, psychological and physical trauma to a pregnant lady. This may put her in to increased risk of depression and anxiety for up to one year from the pregnancy loss [3]. Some of the side effects like bleeding and infection may be a life-threatening event to a pregnant woman. As this is a significant issue among women in their reproductive life, its management should be optimized to reduce the mental, physical and social trauma on the woman. Three basic available options to manage early pregnancy loss are expectant, medical and surgical. All these methods have unique risks and benefits. A woman with incomplete miscarriage, but hemodynamically stable and free of infection will be a good candidate for expectant management. This is the first line management option suggested by NICE guideline as it can be managed as an outpatient [4]. Even though this is free of side effects related to drugs and surgery, longer time taken for the complete recovery may interfere with the woman’s quality of life [5].

Suction evacuation is best suited for hemodynamically unstable patient as it provides rapid recovery which gained the popularity over the last 50 years which performed under general anaesthesia in an operation theatre. Anaesthesia related complications, uterine perforation, cervical injuries, heavy bleeding, localized pelvic infections and requiring repeat suction are the common complications associated with this [6]. Place of the medical management for first trimester missed miscarriage gained the attention of the developing pharmaceutical world during last few years. As a result of that, suitability of surgical management as the first line treatment option for the management of first trimester missed miscarriage were questioned [7-9]. Misoprostol and Mifepristone gained the best attention as the drugs of choice out of all the pharmaceuticals for the medical management of first trimester missed miscarriage. Unique characteristics of the Misoprostol (15-deoxy-16-hydroxy-16-methyl PGE1) have been able to gained significant place in medical management of first trimester missed miscarriage. Other than using in this purpose, Misoprostol is widely used in Obstetrics and Gynaecology for cervical ripening before uterine instrumentation, induction of labour, prevention and treatment of post-partum haemorrhage due to uterine atony [10].

One advantage of Misoprostol is it can be absorbed in various routes including oral, sublingual, vaginal and rectal. Misoprostol acid is the metabolite produce from the liver after the metabolism which causes cervical ripening, uterine contractions, gastric acid secretion reduction by acting on prostaglandin receptors. Misoprostol acts on both gravid and non-gravid uterus. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps and fever are few common side effects of this drug [11-13]. Misoprostol was licensed to use in Sri Lanka according to the circular that was issued by the Ministry of Health [10]. Extra care should be taken when use this drug on patients with asthma, cervicitis, vaginitis, hypertension or hypotension, anaemia, jaundice, diabetes or epilepsy. Misoprostol should not be used in patients with acute pelvic inflammatory disease, hypersensitivity to Misoprostol, active renal, hepatic or cardiovascular disorder. Uterine rupture and malignant hyperthermia are the life-threatening side effect of this medication [10]. Selecting the best candidate for the medical management thus plays a major role.

Material and methods

This retrospective descriptive study was conducted at Teaching Hospital, Mahamodara, Galle (THMG), Sri Lanka to describe the demographic, obstetrics and radiological parameters associated with first trimester pregnancy loss and its medical management. Ethical clearance was obtained from the university Ethical review committee and administrative approval was gained from the Director of THMG.

first trimester missed miscarriage was diagnosed according to the NICE guidelines and included into the study. This diagnosis was based on ultrasound scan findings [5]. Embryonic miscarriage was diagnosed according to following two criteria.

- When crown-rump length (CRL) <7mm>

- When CRL>7mm with a TVS, absence of fetal cardiac activity should be confirmed by two independent operators.

Anembryonic miscarriage was diagnosed with following two criteria.

- When the mean gestational sac diameter (MGSD) is less than 25mm with a TVS, absence of fetal pole should be confirmed in two consecutive TVS which were done at least seven days apart.

- When the MGSD is more than 25mm with a TVS, absence of a fetal pole should be confirmed by two independent operators.

Post Misoprostol endometrial thickness measured in mid sagittal plane with a TVS, less than 15mm was considered as complete uterine evacuation or successful medical management [14].

Patients with first trimester missed miscarriage with less than 13 weeks of menstrual gestational age (which correspond up to 90 days) who were managed with two doses of 800 micro grams vaginal Misoprostol in two doses which were given 3 hours apart (Ministry of Health guideline [10]) were selected to this study as the study population. Misoprostol issuing register was used to identify the patients.

Following patients were excluded from the study.

- Significant amount of missing data

- Uncertain menstrual period

- Not complied with the existing protocol.

Sample size was calculated by the G power software. Eligible patient’s bed head tickets were retrieved by the record room with prior permission. Data collecting officer (who was well trained in collecting data) used a pre-tested validated data retrieval sheet to collect data from the bed head tickets. This was done under direct supervision of the researcher.

Results

The total number of cases available for analysis was 167 out of 208, with 40 features recorded (Table 1: Features Collected). Two additional features were derived by combining two recorded data points (POA in Days from POA Weeks and POA Days Components, Blood Group from ABO and Rh components).

Table 1: Features Collected

| Feature | Type |

| Age | Numerical |

| Ethnicity | Categorical |

| Education Level | Categorical |

| Employed | Categorical |

| Employment | Categorical |

| Height in cm | Numerical |

| Weight in kg | Numerical |

| BMI (kg/m²) | Numerical |

| Total Pregnancies (including this pregnancy) | Numerical |

| Number of Living Children | Numerical |

| Number of Vaginal Deliveries | Numerical |

| Number of Caesarean Sections | Numerical |

| Total Caesarean Sections | Numerical |

| Previous Myomectomies | Categorical |

| Previous Classical Caesarean Sections | Categorical |

| Congenital Uterine Anomaly History | Categorical |

| Previous Abortions | Categorical |

| Treatment for Previous Abortions | Categorical |

| Contraceptive Used Before Pregnancy | Categorical |

| Pregnancy Planned | Categorical |

| Last Menstrual Period Certain | Categorical |

| Vaginal Bleeding During Current Pregnancy | Categorical |

| Gravida (G) | Numerical |

| Parity (P) | Numerical |

| Children (C) | Numerical |

| POA - Weeks | Numerical |

| POA - Days | Numerical |

| POA in Days | Numerical |

| Bleeding through Cervical Os | Categorical |

| Gestational Sac Size | Numerical |

| Presence of Foetal Poles | Categorical |

| Crown-Rump Length | Numerical |

| ABO Blood Group | Categorical |

| Rhesus Blood Group | Categorical |

| Serum Beta hCG | Numerical |

| Interval Between Diagnosis and Treatment | Numerical |

| Anteroposterior Product Thickness | Numerical |

| Medical Management Result | Categorical |

| Next Step When Unsuccessful | Categorical |

| Side Effects Experienced by Patient | Categorical |

| Special Events During Hospital Stay | Categorical |

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of Numeric Features

| Feature | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Age | 167 | 18 | 45 | 31.87 | 6.481 |

| Height in cm | 167 | Missing | Missing | Missing | Missing |

| Weight in kg | 167 | Missing | Missing | Missing | Missing |

| BMI | 167 | Missing | Missing | Missing | Missing |

| Total Pregnancies | 167 | 1 | 6 | 2.32 | 1.219 |

| Living Children | 167 | 0 | 4 | 1.04 | 0.959 |

| Vaginal Deliveries | 167 | 0 | 4 | 0.78 | 0.970 |

| Caesarean Sections | 167 | 0 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.557 |

| Total Caesarean Sections | 167 | 0 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.557 |

| Gravida (G) | 167 | 1 | 6 | 2.32 | 1.219 |

| Parity (P) | 167 | 0 | 4 | 1.10 | 0.961 |

| Children (C) | 167 | 0 | 4 | 1.04 | 0.959 |

| POA - Weeks | 167 | 4 | 12 | 10.22 | 1.611 |

| POA - Days | 167 | 0 | 6 | 2.74 | 2.004 |

| POA in Days | 167 | 30 | 90 | 74.29 | 11.327 |

| Gestational Sac Size (cm) | 167 | 1.20 | 7.00 | 4.05 | 1.42 |

| Crown-Rump Length (cm) | 120 | 0.40 | 6.70 | 3.29 | 1.67 |

| Serum Beta hCG | 167 | Missing | Missing | Missing | Missing |

| Interval Between Diagnosis and Treatment | 166 | 1 | 4 | 1.19 | 0.535 |

| Anteroposterior Product Thickness | 164 | 5.7 | 28.0 | 14.31 | 4.88 |

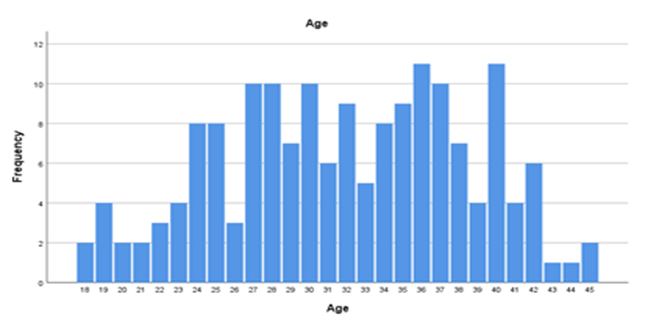

The mean age of patients was 31.87 with a standard deviation of 6.481 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Age Distribution

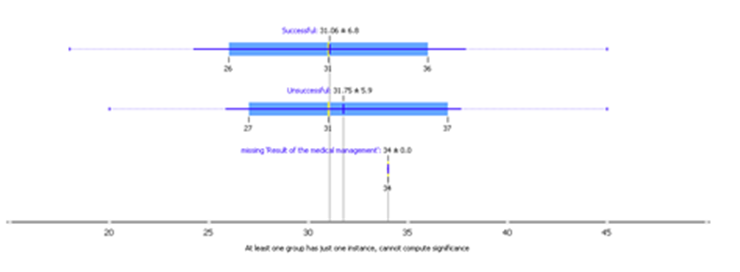

Figure 2: Age Statistics in Success and Failures

Table 3: Distribution of Ethnicity

| Ethnicity | Frequency |

| Muslim | 15 |

| Sinhala | 151 |

| Tamil | 1 |

| Total | 167 |

One hundred fifty-one patients were Sinhalese, 15 were Muslims, and 1 was Tamil

Table 4: Blood Groups

| Blood Group | Frequency | Percent |

| Missing | 28 | 16.8 |

| A | 30 | 18.0 |

| AB | 5 | 3.0 |

| B | 42 | 25.1 |

| O | 62 | 37.1 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 |

The level of education, employment status, and contraceptive methods used were inconsistently recorded and thus excluded from analysis. The certainty of the last regular menstrual period was confirmed in 164 cases, with only 2 uncertain.

Table 5: Last Menstrual Period Certainty

| Certainty | Frequency |

| Yes | 164 |

| No | 2 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Total | 167 |

The total number of pregnancies, including the current one, varied: 54 patients (32.3%) had 1 pregnancy, 47 (28.1%) had 2, 32 (19.2%) had 3, 27 (16.2%) had 4, 6 (3.6%) had 5, and 1 patient (0.6%) had 6 pregnancies.

Table 6: number of pregnancies

| Number | Frequency | Percent |

| 1 | 54 | 32.3 |

| 2 | 47 | 28.1 |

| 3 | 32 | 19.2 |

| 4 | 27 | 16.2 |

| 5 | 6 | 3.6 |

| 6 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 |

The number of living children was as follows: none in 59 (35.3%), one in 55 (32.9%), two in 41 (24.6%), three in 11 (6.6%), and four in 1 (0.6%).

Table 7: Number of Living Children

| Number | Frequency | Percent |

| 0 | 59 | 35.3 |

| 1 | 55 | 32.9 |

| 2 | 41 | 24.6 |

| 3 | 11 | 6.6 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 |

The number of vaginal deliveries ranged from none (88 patients, 52.7%) to four (1 patient, 0.6%).

Table 8: Number of Vaginal Deliveries

| Number of Vaginal Deliveries | Frequency | Percent |

| 0 | 88 | 52.7 |

| 1 | 38 | 22.8 |

| 2 | 31 | 18.6 |

| 3 | 9 | 5.4 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 |

Table 9: Number of Caesarean Sections

| Number of Caesarean Sections | Frequency | Percent |

| 0 | 135 | 80.8 |

| 1 | 22 | 13.2 |

| 2 | 10 | 6.0 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 |

The history of previous abortions was recorded for 167 patients, with 34 (20.4%) reporting a history of abortion. The treatment for these abortions included medical management (30 cases), combined medical and surgical management (2 cases), and spontaneous expulsion (2 cases).

Table 10: History of Previous Abortions

| Previous Abortions | Frequency |

| No | 133 |

| Yes | 34 |

| Total | 167 |

Table 11: Treatment for Previous Abortions

| Treatment Method | Frequency | Percent |

| Medical Management | 30 | 18.0 |

| Medical & Surgical Management | 2 | 1.2 |

| Spontaneous Expulsion | 2 | 1.2 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 |

Table 12: Gravida (G)

| Gravida (G) | Frequency | Percent |

| 1 | 56 | 33.5 |

| 2 | 46 | 27.5 |

| 3 | 42 | 25.2 |

| 4 | 20 | 12.0 |

| 5 | 3 | 1.8 |

| 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

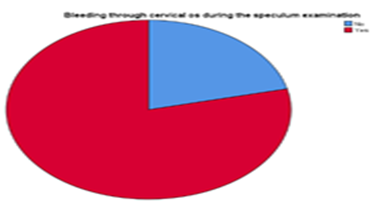

Figure 3: Bleeding through the cervical os during the speculum examination

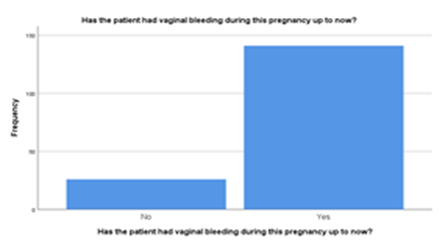

Figure 4: History of per vaginal bleeding

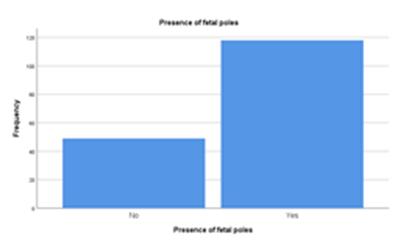

Figure 5: Presence of fetal poles

Table 13: Result of the medical management

| Result of the medical management | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 1 | .6 | .6 | .6 | |

| Successful | 104 | 62.3 | 62.3 | 62.9 | |

| Unsuccessful | 62 | 37.1 | 37.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Table 14: Next management step for unsuccessful medical management.

| If unsuccessful, what was the next step? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 105 | 62.9 | 62.9 | 62.9 | |

| ERPC | 51 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 93.4 | |

| Repeat Misoprostol | 11 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Table 15: Side effects profile

| Side effects experienced by the patient | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 128 | 76.6 | 76.6 | 76.6 | |

| Abdominal Cramps | 2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 77.8 | |

| Abdominal Cramps, Faintishness | 1 | .6 | .6 | 78.4 | |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | .6 | .6 | 79.0 | |

| Faintishness | 1 | .6 | .6 | 79.6 | |

| Fever | 14 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 88.0 | |

| Fever, Chills | 1 | .6 | .6 | 88.6 | |

| Fever, Nausea, Vomiting | 1 | .6 | .6 | 89.2 | |

| Mild chest pain | 1 | .6 | .6 | 89.8 | |

| Nausea, Vomiting | 15 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 98.8 | |

| Nausea, Vomiting, Faintishness | 1 | .6 | .6 | 99.4 | |

| Tachycardia | 1 | .6 | .6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who underwent treatment for early pregnancy failure at our institution. The findings highlighted several important aspects, such as the predominance of Sinhalese ethnicity (90.4%), with a notable proportion of patients (37.1%) having blood group O. The age of patients ranged from 18 to 45 years, with a mean of 31.87 years. Most patients (32.3%) had one pregnancy, and 35.3% had no living children, reflecting a diverse reproductive history. The relationship between the number of previous pregnancies and delivery mode revealed that a substantial proportion of patients (52.7%) had not undergone any vaginal deliveries, suggesting the potential impact of previous cesarean sections or other complications. This finding aligns with the growing trend of cesarean deliveries observed globally. The number of patients with a history of previous abortions was 20.4%, and most of these cases (18%) were managed with medical methods. The presence of certain features, such as blood group distribution and gravidity, is consistent with findings from similar studies conducted in different regions. These characteristics are useful for understanding the patient profile and tailoring treatment protocols accordingly. However, as noted, the lack of consistency in the recording of some features (e.g., education level, employment status) poses a challenge to fully interpreting the socio-economic factors that could influence treatment outcomes. Even though success rate of the medical management in this study came as 62%, success rate which was reported by one of the previous Sri Lankan studies was 54% [15]. International literature shows that this varies between 54% to 84% [15-16]. Usage of different protocols, usage of Mifepristone, ethnic variation and time given for the drug activity may have contributed to these differences. Even though this study showed 8% side effect among the patients, this didn’t show serious side effect like uterine rupture.

Limitations

Despite providing valuable insights, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size (167 patients) may not fully represent the broader population of patients experiencing early pregnancy failure, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, the inconsistent data recording for certain variables, such as education level and employment status, may have led to incomplete or biased conclusions regarding socio-economic factors. Additionally, a lack of follow-up data on long-term outcomes could prevent a comprehensive evaluation of the long-term effects of the treatments on the patients' future pregnancies and reproductive health. Furthermore, while we accounted for common clinical features, the study did not delve into more specific aspects, such as the genetic or environmental factors that may contribute to pregnancy failure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study provides an important overview of the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients treated for first trimester missed miscarriage in our institution. The findings suggest that factors such as age, parity, and previous obstetric history significantly influence the clinical approach and treatment outcomes. The study highlights the need for further research into the socio-economic and psychological factors associated with early pregnancy failure, as well as the development of more standardized data recording practices. Despite some limitations, the study offers useful insights for clinicians and policymakers working to improve care for patients with first trimester missed miscarriage.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

Self-funded.

References

- (2006). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The management of early pregnancy loss. Greentop Guideline No. 25. London (UK): RCOG.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Warburton D, Fraser FC. (1964). Spontaneous abortion risks in man: data from reproductive histories collected in a medical genetics unit. Am J Hum Genet, 16(1):1-25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Graiebel CP, Halvorsen J, Golemon TB, Day AA. (2005). Management of spontaneous abortion: American Family Physician, 72(7):1243-1250.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Edmonds DK. (2007). Dewhurst’s Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 7:94-99.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2019). Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage, NICE guideline. 126.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2010). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Consent advice No 10. June. London (UK): RCOG.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Macrow P, Elistein M. Managing miscarriage medically. BMJ.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ballagh SA, Harris HA, Demasio K. (1998). Is curettage needed for uncomplicated incomplete spontaneous abortion? Am J Obstet Gynecol, 179(7298):1279-1282.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jurkovic D, Ross JA, Nicolaides KH. (1998). Expectant management of missed miscarriage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 105(6):670-671.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2014). Sri Lanka College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bennett PN, Brown MJ. (2003). Clinical Pharmacology. 629-630.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Craig CR, Stizel RE. (1997). Modern pharmacology with clinical applications. 716-721.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tang O S, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Ho P C (2007). Misoprostol: Pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 99(S2):1607.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nielsen S, Hahlin M, Oden A. (1996). Using a logistic model to identify women with first trimester spontaneous abortion suitable for expectant management. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 103(12):1230-1235.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Liyanage PLGC, Dassanayaka DLW, Ponnamperuma T. (2018). Effectiveness of Misoprostol in the management of miscarriages in patients admitted to Teaching Hospital Mahamodara. Sri Lanka Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Abstractbook, 40th Annual Academic Sessions of SLCOG. 79-80.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zhang J. (2005). A Comparison of Medical Management with Misoprostol and Surgical Management for Early Pregnancy Failure. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353(8):761-769.

Publisher | Google Scholor