Research Article

Feto-Maternal Outcomes and Associated Factors with Severe Preeclampsia among Pregnant Women in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia: Unmatched Case-Control Study

- Beker Ahmed Hussein *

- Wogene Morka Regassa

- Yirga Wondu Amare

Master in Reproductive and Maternal Health, Arsi University, department of Midwifery, Asella, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Beker Ahmed Hussein, Master in Reproductive and Maternal Health, Arsi University, department of Midwifery, Asella, Ethiopia.

Citation: Beker A. Hussein, Wogene M. Regassa, Yirga W. Amare. (2024). Feto-Maternal Outcomes and Associated Factors with Severe Preeclampsia among Pregnant Women in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia: Unmatched Case-Control Study. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(3):1-9. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.24.039

Copyright: © 2024 Beker Ahmed Hussein, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 29, 2024 | Accepted: March 18, 2024 | Published: March 22, 2024

Abstract

Purpose: Severe preeclampsia is commonly identified by progressive deterioration of both maternal and fetal conditions. The motivation behind this study was the lack prior study in the area plus a concern over an increase in adverse outcomes of severe preeclampsia cases necessitates an investigation of associated factors and feto-maternal outcomes among severe preeclampsia women admitted in the maternity wards of Arsi zone.

Methods: At four comprehensive hospitals in the Arsi districts that were chosen at random, a case-control study involving document review was carried out. The file Numbers of 246 controls and 62 clients with severe preeclampsia were extracted using a checklist. SPSS version 21 was used for analysis after epi.info version 7 was used for data entry. In the multivariate analysis, a P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance.

Results: All severe preeclampsia women admitted to the Hospital survived. Six (9.7%) of babies Born from the cases had low APGAR scores, 14 (22.6%) of the babies were premature and 9(14.55) of them had low birth weight (<2.5Kg). Stillbirth with 3(4.8%) and early neonatal death with 2(3.2%) were documented. Previous history of PIH (AOR 42.5; 95% CI 8.9 – 200.9), multiple gestations (AOR: 9.4; 95%CI 3.03-29.6), and first-time pregnancy (AOR 2.2; 95%CI 1.04-4.6) has a significant association with severe preeclampsia.

Conclusion: While severe preeclampsia did not increase maternal death, it did increase perinatal mortality by a considerable amount. Consequently, further work needs to be done to enhance perinatal outcomes.

Keywords: preeclampsia; anticonvulsant; perinatal; arsi zone

Introduction

When a previously normotensive woman experiences additional episodes of hypertension and proteinuria during her pregnancy, it is known as preeclampsia [1-3]. Severity is defined as follows: systolic blood pressure greater than 160 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure greater than 110 mm Hg, proteinuria greater than 5 mg in a 24-hour urine specimen, oliguria, cerebral or visual abnormalities, pulmonary edema, impaired liver function, or the presence of thrombocytopenia [3]. Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-specific multisystem illness with an unclear origin [4,5]. It is more common in primigravida, young mothers (under 18), mothers over 35, new partner pregnancies, women with underlying hypertension, multiple pregnancies, molar pregnancies, and mothers with diabetes [6]. Severe preeclampsia can occur during pregnancy, labor, and delivery. It can also lead to a variety of severe maternal complications, such as low platelet counts, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), abruption placenta, hepatic and renal failure, hemolysis, and elevated liver enzymes (HELLP syndrome). Under these conditions, there may be placental abruption or malfunction, which can result in premature birth, stillbirth, intrauterine fetal mortality, fetal growth restriction, and neonatal hypoxia [7]. Because of the terrible consequences, for every woman who passes away from severe preeclampsia, twenty more will experience severe morbidity or disability [8]. The disease's unexpected nature combined with late patient presentation provides for a severe impact on poorer nations [9].

Around the world, there are differences in the prevalence of severe preeclampsia. For instance, in Western nations [10], the incidence is between 0.6% and 1.2%, but in India, it is 3.3%.9 Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy contribute to the death of 9.1% of maternal death [11] and are identified as the third leading cause of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa [12]. In Ethiopia alone hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a cause for 19% of maternal mortality [13]. According to a study conducted at the Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, preeclampsia and eclampsia are responsible for 67.4% and 27.8% of pregnancy-related hypertension diseases, respectively [14]. Timely identification and treatment are essential to avoid unfavorable feto-maternal consequences from severe preeclampsia [15]. Although delivery is usually appropriate for the mother, the premature fetus may not benefit from it. It is currently widely accepted that if a mother has severe preeclampsia and her gestational age is greater than 34 weeks, she should be encouraged to give birth. Some writers advise expectant treatment for women whose gestational age is less than 34 weeks in an effort to extend pregnancy and enhance fetal outcomes [9, 10] in the course of treating severe preeclampsia. The preferred medication for preventing seizures is magnesium sulfate, and hydralazine is frequently taken up until the blood pressure falls below 160/110 mm Hg [16]. Therefore, a concern about adverse consequences and the absence of a comprehensive prior study in the area necessitates an investigation of feto-maternal outcomes and associated factors with severe preeclampsia among women admitted in the maternity wards of the Arsi zone.

Methods and material

Study design

An unmatched case-control study involving patients’ document review was conducted to find out factors associated with severe preeclampsia and its feto-maternal outcomes among women admitted in Arsi zone between 1st July 2018 to 30 June 2022 G.C

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Complete cards of severe preeclampsia (cases) and healthy clients (controls) were included in the study. Severe preeclampsia cases with incomplete records and case fills of the controls with known medical diseases such as anemia, haemoglopathy, diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders, cardiac diseases, and mental and renal diseases were excluded.

Sampling

The sample size for this case-control study was calculated using stat. calculation in epi. Info version 7 software. The calculated total sample size was 308 individuals- 62 cases and 246 controls. Four comprehensive hospitals located in Arsi districts which have served at least five years since their establishment were selected for the study. Each file of the cases and controls was extracted from the card room using the file number available on our sample frame.

Data collection

Following an examination of the literature, log books, and client records, an English version data abstraction form was created. Eight experienced senior midwives or nurses from the four hospitals in the Arsi zone were responsible for gathering the data, and four supervisors oversaw the entire process. In order to identify cases of severe preeclampsia, registration identifying numbers were employed. Their case notes and other pertinent information were then collected. The study included the next immediate controls that occurred sequentially after each severe preeclampsia case, based on the determined sample interval. In case any control data was missed, the subsequent serial number was taken into account.

Data processing and analysis

Data was coded, inputted, and transferred from version 7 of epi.info to version 21 of SPSS for analysis. To find the frequencies, means, standard deviations, and percentages of the variables, descriptive statistics were calculated. In order to control confounding factors, variables that had a p-value of less than 0.25 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. A statistically significant relationship was indicated when the multivariate analysis's p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical clearance

A letter of approval was obtained from Arsi University, college of health science ethical and review committee. The ethical committee approved the commencement of the study without considering the need for informed consent as it was difficult to get it from discharged individual clients in a case-control study involving a review of medical records. This formal letter was submitted to the zonal health office. At all levels, officials were contacted and permission to begin the study was obtained. The purpose, aim, and advantage of the study were explained to the concerned bodies of the hospitals adequately and their verbal and written consent was secured.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

For the investigation, 308 study participants' records were examined. Of these, 246 were controls with no known medical issues, and 62 were cases. The standard deviation was + 5.2 and the mean age was 27.8. Of the 266 participants, 86.4 percent were in the 20–34 age range. Of the participants, 176 (57.1%) and 132 (42.9%) were estimated to be from rural and urban areas, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants in selected Hospitals of Arsi zone, 2022 G.C

| Type of client | Cases (%) | Controls (%) | Total (%) |

| Age | |||

| <20> | 5(8.1) | 6(2.4) | 11(3.6) |

| 20-34Years | 48(77.40) | 218(88.6) | 266(86.4) |

| >35 years | 9(14.5) | 22(8.9) | 31(10.1) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 32(51.6) | 144(58.5) | 176(57.1) |

| Urban | 30(48.4) | 102(41.5) | 132(42.9) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

Reproductive/obstetric history

The majority of the cases (61.3%) and 67.9% of the controls were multigravidas. Just over half (51.6%) of the cases and 34.9 % of the controls were para–I. Almost all (95.2%) of the cases and 92.7 % of the control had antenatal care follow-up for their recent pregnancy. The majority of the control (96%) and 76.5% of the cases gave birth at >34 weeks of gestation. The onset of labor among 51.6% of the cases and 16.6% of the controls was by induction. Regarding mode of delivery, the majority (62.9 %) of cases of severe preeclampsia and 62.6 % of the controls had spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) (Table 2).

Table 2: Reproductive/obstetric factors of study participants in Arsi zone, 2022 G.C.

| Type of client | Cases (%) | Controls (%) | Total (%) |

| Garavida | |||

| Primigravid | 24(38.7) | 79(32.1) | 103(33.4) |

| Multigravid | 38(61.3) | 167(67.9) | 205(66.6) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

| Parity | |||

| Para I | 32(51.6) | 86(34.9) | 118(38.3) |

| Para II-IV | 24(38.7) | 137(55.6) | 161(52.3) |

| Para >V | 6(9.6) | 23(9.3) | 29(9.4) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

| ANC follow up | |||

| Yes | 59(95.2) | 228(92.7) | 287(93.2) |

| No | 3(4.8) | 18(7.3) | 21(6.8) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

| GA at delivery | |||

| <34> | 15(23.5) | 10(4.0) | 24(7.8) |

| >34 weeks | 47(76.5) | 236(96) | 284(92.2) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

| Onset of labour | |||

| Induced | 32(51.6) | 41(16.6) | 73(23.7) |

| Spontaneous | 30(48.4) | 205(83.4) | 235(76.3) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| SVD | 39(62.9) | 154(62.6) | 193(62.7) |

| Assisted | 6(9.7) | 49(19.9) | 55(17.8) |

| C/s | 17(27.4) | 43(17.5) | 60(19.5) |

| Total | 62(100) | 246(100) | 308(100) |

Risk factors among the cases and controls

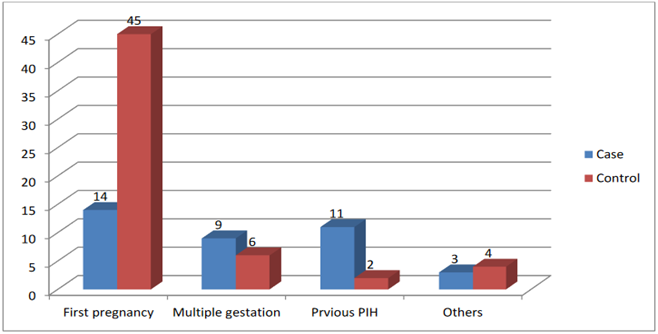

Cases and controls were assessed for the possible existence of one or more risk factors. The majority (n=45) of the controls were nulliparous Vs (n=14) of the cases. Previous pregnancy with pregnancy-induced hypertension (n=11) was seen among the cases Vs (n=2) among the controls. Multiple gestations were reported in 9 cases and 6 controls. Another risk factor such as a new partner for their recent pregnancy was reported in 3 cases and 4 controls respectively. (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Risk factors among the cases and controls, 2022 G.

Medications received for the management of severe preeclampsia

Sixty (96.8%) of severe preeclamptic patients received anticonvulsants (magnesium sulfate) before complications occurred. Fifty-two (83.9%) of the cases received antihypertensive drugs earlier before complications occurred (Table 3).

Table 3: Drugs given for management of Sever preeclampsia, 2022G.C

| Medications | Frequency | Percent | |

| Anticonvulsant received | Early before complication | 60 | 96.8 |

| Late after complication | 2 | 3.2 | |

| Total | 62 | 100 | |

| Antihypertensive received | Late after complication | 10 | 16.1 |

| Early before complication | 52 | 83.9 | |

| Total | 62 | 100.0 | |

Maternal Outcome of Severe Preeclampsia

All the cases and controls selected for this study were survived. No maternal death had been recorded on the registration or card. Other maternal complications among the cases and control were assessed. Three (4.8%) of the cases and 5(2%) of the controls developed PPH. Only 1 case developed pulmonary edema but none of the control groups experienced pulmonary edema. Abruption placenta was diagnosed among 1(1.6%) of the cases and 2(0.8%) of the control groups. Other, complications like renal failure and DIC were not identified in any of the cases and controls (Table 4).

Table 4: Maternal complication among cases and controls in Arsi zone, 2022 G.C

| PPH | Cases | Controls |

| Yes | 3(4.8) | 5(2.0) |

| No | 59(95.2) | 241(98) |

| Pulmonary edema | ||

| Yes | 1(1.6) | 0(0) |

| No | 61(98.4) | 246(100) |

| Abruption placenta | ||

| Yes | 1(1.6) | 2(0.8) |

| No | 61(98.40 | 244(99.2) |

| HELLP syndrome | ||

| Yes | 14(22.5) | 0(0) |

| No | 48(77.5) | 246(100) |

| Renal failure | ||

| Yes | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| No | 62(100) | 246(100) |

| DIC | ||

| Yes | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| No | 62(100) | 246(100) |

Fetal outcomes I severe preeclampsia

Six (9.7%) of the cases and 24(9.8%) of the controls had a Low APGAR score. Fourteen (22.6%) of the cases and 22(8.9%) of the controls were premature babies, 9(14.55) of the cases and 8(3.3 %) of controls had low birth ( less than 2.5Kg). Stillbirth is reported among 3(4.8%) of the cases and 5(2%) of the controls. Early neonatal death is documented among 2(3.2%) and 3(1.2%) of the cases and controls respectively (Table 5).

Table 5: Fetal outcomes among severe preeclampsia patients and the controls, 2020GC

| Fetal outcome | Case | Control |

| Low APGAR score | 6(9.7%) | 24(9.8%) |

| Prematurity | 14(22.6%) | 22(8.9%) |

| Low birth weight | 9 (14.5%) | 8(3.3%) |

| Stillbirth | 3(4.8%) | 5(2.0%) |

| Early neonatal death | 2(3.2%) | 3(1.2%) |

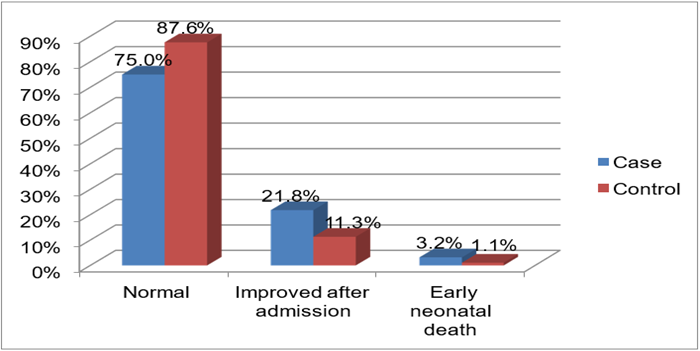

Forty-eight (75%) of the cases & 246(87.6%) of the controls had normal fetal outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Major fetal out comes among the cases and controls, 2022 G.C

Factors associated with Severe preeclampsia

Out of 62 cases, 11(17.7%) and of 246 controls, 2(0.8%) had previous history of PIH. In this study, it is proved that there is an association between severe preeclampsia and a previous history of pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH). Women with a previous history of PIH have a higher chance of developing severe preeclampsia than those not having the history (AOR 4the 2.5; 95% CI 8.9 – 200.9). Women with multiple gestations have about 9 times the chance of encountering severe preeclampsia than women with singleton pregnancy (AOR9.4; 95%CI 3.03-29.6). The multiple regression analysis showed the existence of a significant association between first pregnancies and severe preeclampsia. Women who got pregnant for the first time had approximately 2 times more likely chance of being exposed to severe preeclampsia compared to the multi-gravid. (AOR; 2.2; 95% CI 1.04-4.6). There is also a statistically significant association between mode of delivery (SVD, Assisted delivery, and C/S) and severe preeclampsia (Table 6).

Table 6: Factors associated with severe preeclampsia among study participants in selected Arsi zone hospitals, 2022 G.C.

| Variables | Case | Control | COR:95% C. I. for EXP(B) | AOR:95% C.I. for EXP(B) |

| Previous PIH | ||||

| Yes | 11(17.7%) | 2(0.8%) | 26.3(5.6,122.3) * | 42.5(8.9,200.9) ** |

| No | 51(82.350 | 244 | 1 | 1 |

| Multiple gestations | ||||

| Yes | 9(14.5%) | 6(2.4) | 7.6(2.6,22.5) * | 9.4(3.03,29.6) ** |

| No | 53(85.5%) | 240(97.6%) | 1 | 1 |

| First pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 14(22.5%) | 45 (18.2%) | 1.3(.67,2.7) | 2.2(1.04,4.6) ** |

| No | 48(77.5%) | 201(81.8%) | 1 | 1 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| SVD | 39(62.9%) | 154(62.6%) | 1.6(.83,1.1) | 1.3(.62,3.0) |

| Assisted delivery | 6(9.6%) | 49(19.9%) | 3.1(3.1,8.7) | 1.8(.59,5.5) |

| C/S | 17(27.4%) | 43(17.4%) | 1 | ** |

| PPH | ||||

| Yes | 3(4.8%) | 5(2%) | .40(.09,1.7) | 1.9(.35,11.05) |

| No | 59(95.2%) | 241(98%) | 1 | 1 |

| Abruption placenta | ||||

| Yes | 1(1.6%) | 2(0.8%) | 2.0(.17,22.4) | 2.9(.22,37.42) |

| No | 61(98.4%) | 244(99.2%) | 1 | 1 |

Note: SVD: Spontaneous vaginal delivery, PIH: Pregnancy-induced hypertension, C/S: cesarean section, PPH: Postpartum hemorrhage, * P less than 0.25 **P less than 0.05

Factors associated with severe preeclampsia adverse fetal outcomes

Prematurity (COR: 2.6; 95% C.I; 1.26, 5.47) and low birth weight (COR: 5.0; 95% C.I:1.86, 13.70) had a significant association in the bivariate analysis but had no association with severe preeclampsia in the multivariate analysis. Similarly Low APGAR scores, stillbirth, and early neonatal deaths have no significant association with severe preeclampsia as shown in the final model (Table 7).

Table 7: Association between adverse fetal outcomes & severe preeclampsia in Arsi zone, 2022 G.C

| Variables | Case | Control | COR 95% C.I .for EXP(B) | AOR:95% C.I. for EXP(B |

| Low APGAR score | ||||

| Yes | 6(9.7%) | 24(9.8%) | .88 (.34,2.27) | .756 (.27, 2.1) |

| No | 56(90.3% | 222(90.2%) | 1 | 1 |

| Prematurity | ||||

| Yes | 14(22.6%) | 22(8.9%) | 2.6 (1.26,5.47) * | 2.12(.93,4.8) |

| No | 48(77.4% | 224(91.1%) | 1 | 1 |

| Low birth weight | ||||

| Yes | 9 (14.5%) | 8(3.3%) | 5.0(1.86,13.70) * | 2.59(.82,8.1) |

| No | 53(85.5%) | 238(96.7%) | 1 | 1 |

| Stillbirth | ||||

| Yes | 3(4.8%) | 5(2.0%) | 2.4(.57,10.54) | 2.71(.62,11.7) |

| No | 59(95.2%) | 241(98%) | 1 | 1 |

| Early neonatal death | ||||

| Yes | 2(3.2%) | 3(1.2%) | .41(.06,2.50) | 4.52(.62,33.0) |

| No | 60(96.8%) | 243(98.8%) | 1 | 1 |

* P less than 0.25; **P less than 0.05

Discussion

The purpose of this institutional-based case-control study is to evaluate the risk factors for severe preeclampsia and the feto-maternal outcome that results from it. In this investigation, we discovered that 92.7% of the control group and nearly all (95.2%) of the patients received prenatal follow-up care. Compared to a report from the Amhara region, where only 69.1% of the respondents had an ANC follow-up, this is significantly superior. Regarding the commencement and mode of delivery, 37.7% of respondents in the Amhara region gave birth to 51.6% of cases, whereas 62.9% of cases gave birth by SVD versus 29.8% in the Amhara region, and 17.4% of cases underwent a cesarean section versus 27.9% (consistent report) in the Amhara region [17]. In our investigation, patients with severe preeclampsia who received anticonvulsant (magnesium sulfate) and antihypertensive medication prior to complications were 96.8% and 83.9%, respectively. However, a study carried out at the Amhara referral hospital found that only 58.6% of patients had received both medications prior to complications [17]. This implies a high discrepancy in adhering to the national protocol among hospitals in the provision of anticonvulsant and antihypertensive therapy, this study reports no maternal death among the controls or cases of severe preeclampsia. This is in contrast to research that found that acute renal failure accounted for 1.7% of maternal mortality at Mpilo Central Hospital in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe 12 and a study conducted in Nigeria 12.1% [18]. This variation may be partly attributed to the late presentation of cases and lower quality of care in Mpilo Central Hospital compared to our setup.

In agreement with studies conducted by Abalos E et al 8, Grum T et al [19] and Machano MM et al [20], the results of the current investigation demonstrated a strong correlation between the history of numerous gestations (AOR: 9.4; 95% CI 3.03-29.6), first pregnancies (AOR: 2.2; 95% CI 1.04-4.6), and pregnancy-induced hypertension (AOR: 42.5; 95% CI 8.9 – 200.9) and severe preeclampsia. Our results show that 3 (4.8%) of the cases had a stillbirth, which is significantly fewer than the 103 (28.1%) stillbirths among instances of severe preeclampsia described in research conducted in the Amhara region 17 and Addis Ababa 363(30.2%) [21]. Similarly, a lower proportion of prematurity 14 (22.6%) and low birth weight 9(14.55) are identified among severe preeclamptic women compared to a study in Addis Ababa where 395(32.8%) of the cases gave birth to premature and 363 (30.2%) low birth weight babies respectively [21]. These differences in the proportion of perinatal outcomes among the studies may go with the quality of care delivered in each facility including prenatal care. In this regard, the better perinatal outcome in our study can be taken as a mirror image of better case handling compared to the other facilities included in other studies.

Conclusion

Severe preeclampsia was common among primigravid women, multiple gestations, and in a woman with a previous history of PIH. In this study, severe preeclampsia has not contributed to maternal mortality. However; has contributed to a higher percentage of perinatal mortality (stillbirth and early neonatal mortality) though there wasn’t a statistically significant difference between the cases and controls. Therefore, an effort to reduce adverse fetal outcomes has to be made by healthcare providers through early identification of severely preeclamptic patients and providing anticonvulsants and antihypertensives immediately for whom they deserve.

Declarations

Data availability

The dataset used for analysis is available from the main author upon reasonable request.

Competing interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of financial and other interests

Funding

A total fund of 150,000 Ethiopian birr with a project code of CoHS/R/0061/2019/2020 was received from the Arsi University Office of Research and Publication directorate director.

Authors' contributions

Beker Ahmed took part in conceptualization, and proposal writing, searched the database, supervised data collectors, analyzed, and interpreted results, wrote the first draft of the article, and served as a corresponding author.

Wogene Morka, and Yirga wondu were also involved in supervision, data entry and cleaning, analysis, interpretation, approval of the final version, and manuscript preparation.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An ethical approval letter was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRB) of Arsi University college of health science with reference number of CoHS/R/0061/2019/2020. Following the approval, an official letter of cooperation was written to the concerned bodies by the college to facilitate the support and commitment of responsible bodies. Permission was obtained from the hospital medical director and department of gynecology and obstetrics/maternity. As the study was conducted through review of chart records, the individual patients were not subjected to any harm and personal identifiers during data collection and confidentiality was maintained through not recording the name of the participant on the checklist. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent from study participants was not applicable for this study, and the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRB) of Arsi University waived it. However, all tryouts were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Acknowledgment

Our heartfelt appreciation goes to Arsi University for its financial support and, Arsi Zonal Health Bureau for their cooperation. Our thanks also go to the maternity ward and card room workers for their cooperation in availing and providing necessary data for our studies.

References

- Mammaro A, Carrara S, Cavaliere A, Ermito S, Dinatale A, Pappalardo EM, Militello M, Pedata R. (2009). Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Journal of prenatal medicine, 3(1):1.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Townsend R,O’Brien P, Khalil A. (2016). Current best practice in the management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Integrated blood pressure control, 9:79.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Savita RS etaal, (2009). Maternal and prenatal outcome in sever preeclampsia and eclampsia. south Asian federation of obstetrics and gynecology, 1(3):25-28

Publisher | Google Scholor - Browne JL, Vissers KM, Antwi E, Srofenyoh EK, Vander linden EL, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K. (2015). prenatal outcomes after hypertensive disorders in pregnancy in a low resource setting. Tropical medicine and international health, 20(12):1778-1786.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varnier N , Brown MA, Reynolds M, Pettit F, Davis G, Mangos G, Henry A. (2018). Indication for delievery in preeclampsia. Pregnancy hypertension, 11:12-17.

Publisher | Google Scholor - KIlembe FD, Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; Prevalence, maternal complications and prenatal outcomes at Lilongwe central hospital, Malawi (Master`s Thesis).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ye C, Ruan Y, Zou L, Li G, Li C, Chen Y, Jia C, Megson IL, Wei J, Zhang W. (2014). The 2011 survey on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) in China: prevalence, risk factors, complications, pregnancy and prenatal outcomes. PloS one, 9(6):e100180.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Abalos E, Cuesta C, Carroli G, Qureshi Z, Widmer M, Vogel JP, Souza JP. (2014). WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health Research Network. Pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes: a secondary analysis of the W orld H ealth O rganization Multicountry S urvey on M aternal and N ewborn H ealth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121:14-24.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chattopadhyay S, Das A, Pahari S. (2014). Fetomaternal outcome in severe preeclamptic women undergoing emergency cesarean section under either general or spinal anesthesia. Journal of pregnancy.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Norwitz ER, Repke JT, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. (2015). Preeclampsia: Management and prognosis.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muti M, Tshiagna M, Notion GT, Bangure D, Chonzi P. (2015). Prevalence of pregnancy induced hypertension and pregnancy outcomes among women seeking maternity services in Harare, Zimbabwe. BMC cardiovascular disorders, 15(1):11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ngwenya S. (2017). Severe preeclampsia and eclampsia: incidence, complications, and perinatal outcomes at a low-resource setting, Mpilo Central Hospital, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. International journal of women's health, 9:353

Publisher | Google Scholor - Berhe AK, Kassa GM, Fekadu GA, Muche AA. (2018). Prevalence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Ethiopia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 18(1):34.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Terefe W, Getachew Y, Hiruye A, Derbew M, Hailemariam D, Muhiye A. (2015). Paterns of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and associated factors at Debrebirhan referral hospital, north shoa, Amhara region. Ethiopian medical journal, 53.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wolde Z, Segni H, Woldie M. (2011). Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Jima university Specialized hospital. Ethiopian Journal of health Sciences, 21(3).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mooij R, Lugumila J, Mwashambwa MY, Mwampagatwa IH, van Dillen J, Stekelenburg J. (2015). Characteristics and outcomes of patients with eclampsia and severe pre-eclampsia in a rural hospital in Western Tanzania: a retrospective medical record study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 15(1):1-78.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Melese MF, Badi MB, Aynalem GL. (2019). Perinatal outcomes of severe preeclampsia/eclampsia and associated factors among mothers admitted in, North West Ethiopia, 2018. BMC research notes, 12(1):1-6.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Leonard Ogbonna Ajah et al. (2016). The Feto-maternal Outcome of Preeclampsia with Severe Featutres and Eclampsia in Abakaliki, South-East Nigeria. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 10(9): QC18-QC22.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Grum T, Seifu A, Abay M, Angesom T, Tsegay L. (2017). Determinants of pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia among women attending delivery Services in Selected Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a case control study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth,17(1):1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Machano MM, Joho AA. (2020). Prevalence and risk factors associated with severe pre-eclampsia among postpartum women in Zanzibar: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 20(1):1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wagnew M, Dessalegn M, Worku A, Nyagero J. (2016). Trends of preeclampsia/eclampsia and maternal and neonatal outcomes among women delivering in addis ababa selected government hospitals, Ethiopia: a retrospective cross-sectional study. The Pan African medical journal, 25(S2).

Publisher | Google Scholor