Research Article

Fabry's Disease: A Clinical Presentation and an Atypical form in Algeria

1Department of Internal Medicine. Faculty of Medicine, University of Blida, Algeria.

2Central laboratory of biochemistry. Faculty of Medicine, University of Blida, Algeria.

*Corresponding Author: Bachir Cherif Abdelghani, Department of Internal Medicine. Faculty of Medicine, University of Blida, Algeria.

Citation: Bachir C. Abdelghani, Bennouar S, Djebbar Y, Bellahmer S, Taleb A. (2024). Fabry's Disease: A Clinical Presentation and an Atypical form in Algeria. Clinical Case Reports and Studies, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 5(2):1-7. DOI: 10.59657/2837-2565.brs.24.102

Copyright: © 2024 Bachir cherif Abdelghani, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: January 18, 2024 | Accepted: February 02, 2024 | Published: February 09, 2024

Abstract

Introduction: Fabry disease is an X-linked sphingolipidosis, caused by a total or partial deficiency of a lysosomal hydrolase, alpha-galactosidase A. It leads to multi-systemic damage from a very young age. The diagnosis is mainly clinical and confirmed by the measurement of enzymatic activity.

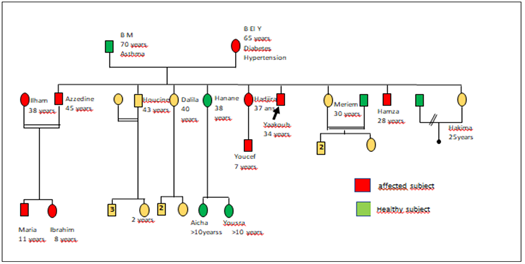

Material and methods: We describe an Algerian family presenting a classic form of Fabry Disease due to a Deletion/Insertion mutation on exon 6. In this family, nine people suffer from Fabry disease [5 male and 4 female]. The youngest is 6 years old and the oldest is 65 years old. All Fabry cases benefited from a complete physical examination and additional tests to assess multi-system involvement.

Results: All patients are symptomatic, whose diagnosis was confirmed by the enzymatic assay of alpha galactosidase A activity which showed a very low level. Genetic analysis found the anomaly in the GLA gene coding for alpha galactosidase A. Angiokeratomas are observed in almost all male subjects. Neuropathic pain and Acro paresthesia appear in all affected people but are more pronounced in men. No serious cerebrovascular damage has been reported.

The index case presents with chronic end-stage renal failure at the hemodialysis stage. On the electrocardiogram, patients have a pathological Cornel and Sokolow index. Only four of our patients were put on enzyme replacement therapy.

Conclusion: Fabry disease is a rare and potentially serious disease because of its renal and cardiac complications. Early diagnosis is crucial. Management of patients with Fabry disease must involve the combination of early symptomatic treatments and enzyme therapy. It is therefore necessary to establish a family tree and inform family members likely to be affected/carriers of the genetic anomaly.

Keywords: fabry disease; sphingolipidosis; alpha galactosidase; x-linked inheritance

Introduction

Fabry disease, or Anderson-Fabry disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum universale, is a sphingolipidosis of X-linked inheritance, due to a total or partial deficiency of a lysosomal hydrolase: alpha-galactosidase A [1]. This leads from an early age to a progressive and ubiquitous accumulation of non-degraded glycosphingolipids. The cutaneous, neurological, nephrological, cardiac, gastrointestinal, ophthalmological, respiratory, cochleovestibular and hematological consequences are all associated with high mortality and a significant deterioration in the patient's life quality. [2]. Angiokeratomas are the most frequent cutaneous manifestation but they are not specific to this disease, so they should be distinguished from isolated angiokeratomas or angiokeratomas associated with systemic diseases. Diagnosis is primarily clinical and requires investigation of a suggestive personal and/or family history; it is confirmed by assaying enzyme activity in leukocytes or by molecular analysis [3]. Management of the disease is multidisciplinary, involving both symptomatic and specific therapies, which help to improve both outcome and quality of life [4,5]. Alpha-galactosidase A replacement enzyme therapy is the cornerstone of specific treatment [6].

Materials and Methods

Here, we report on an Algerian family with a classic form of Fabry disease caused by a deletion/insertion mutation in the exon 6 region of the GLA gene coding for alpha galactosidase A. In this family, nine individuals are affected by Fabry disease (five males and four females). The youngest is 06 and the oldest 65. The index case (case 1) is 34 years old. All Fabry cases benefited from a complete physical examination and further investigations to assess multi-systemic impairment: cardiac (electrocardiogram, echocardiography), neurological (electromyogram (EMG), cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), evoked potentials), otolaryngological (audiogram), ophthalmological (fundus, slit lamp examination), dermatological and renal check-up (microalbuminuria, proteinuria, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and renal ultrasound).

Results

All patients were symptomatic; their diagnosis was confirmed by enzymatic measurement of alpha galactosidase A activity, which showed a very low level in male patients, while lyso GB3, the product of sphingolipid degradation, reached a very high level, especially in the two young male patients, indicating the extent of the enzymatic deficiency. Given the possible inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes, the alpha galactosidase A assay remains within the normal range in 40% of women with Fabry disease. Therefore, genetic analysis is required to identify the abnormality in the GLA gene coding for alpha galactosidase A. Clinical and paraclinical manifestations are shown in Table 1. Angiokeratomas are encountered in almost all male subjects, but are more extensive in case 1. Indeed, in this patient [case 1], they are even present on the lumbar region, external genitalia and thighs.

Neuropathic pain and acroparesthesia occur in all affected patients, although they are more pronounced in men, with only the latter reporting a Fabry episodes with fever, leading to multiple previous hospitalizations. Audiograms revealed sensorineural hearing deficits in cases 1, 2 and 3, requiring the fitting of hearing aids. No major cerebrovascular damage [stroke] has been reported. The index case showed chronic end-stage renal failure at the hemodialysis stage, which was the revelatory form of the disease. Microalbuminuria was found in cases 2, 4 and 5.

None of the patients had cardiovascular manifestations: no reported dyspnea or angina. On auscultation, there were no abnormal murmurs. Blood pressure was normal in all patients.

Table 1: Clinico-biological manifestations in patients with Fabry disease

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | |

| Age (year) / gender | 34/M | 45/M | 28 /M | 40 /F | 38 /F | 65 /F | 11 /F | 08/M | 07 /M |

| Alpha Gal A activity | 07% | 07% | 12% | 42% | 42% | 40% | 03,5% | 07% | 07% |

| Angiokeratoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Extension of angiokeratomas | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ocular manifestations | Yes | yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Neurological disorders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Febrile Fabry crisis | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Acroparesthesia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hypohydrosis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exercise intolerance | No | No | No | Oui | No | No | Oui | No | No |

| Stroke | No | No | No | No | No | No | Oui | No | No |

| Orthostatic hypotension | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Deafness | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| eGFR MDRD (ml/min/1.73m2) | 6 | 91 | 162 | 107 | 135 | 75 | 86 | 69 | 89 |

| Proteinuria (mg/24h) | 1200 | 220 | 500 | 550 | 48 | 102 | 88 | 94 | 155 |

| Cardiac events | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dyspnea | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Angina/Myocardial infarction | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Heart rate (Bpm) | 55 | 65 | 75 | 80 | 75 | 73 | 80 | 65 | 75 |

| ECG abnormalities | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| PR interval (msec) | 160 | 160 | 160 | 120 | 140 | 160 | 150 | 140 | 180 |

| LV hypertrophy / sokolow (mm) | 44 | 34 | 16 | 18 | 33 | 22 | 28 | 31 | 29 |

| Echocardiographic abnormalities | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| LV Mass Index (gr/m2) | 132 | 139 | 72 | 101 | 75 | 79 | 86 | 91 | 90 |

| LV ejection fraction (Simpson) | 75% | 68% | 72% | 78% | 61% | 73% | 59% | 68% | 70% |

| Mitral insufficiency | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Mitral valve thickening | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

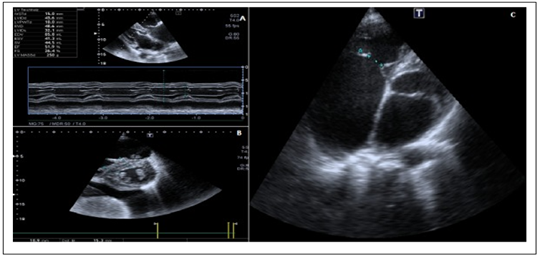

On the electrocardiogram, patients have a pathological Cornel and sokolow index. There are no conduction abnormalities. All had a normal PR interval. Chest X-rays are normal in all cases. Echocardiography showed left ventricular hypertrophy in the index case and the 2nd case (figure 1). Left ventricular ejection fraction was normal. Left ventricular diastolic function parameters were also normal. There was no right ventricular dysfunction. No segmental or global kinetic disturbances were observed. No abnormalities were noted in the patients' aortic sigmoids. Echocardiography was not performed in pediatric patients.

Figure 1: echocardiography: parasternal section and four cavities Fabry disease.

The genetic study was performed for this family with Fabry disease; results are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Genealogical tree showing family members with Fabry disease.

Four of these patients have been put on agalasidase alpha enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), a twice-weekly course of treatment with 07 months of follow-up for the index case and 02 months for the other 3 cases. Further studies are planned to evaluate the efficacy of ERT, especially on the cardiac and renal outcomes of these patients.

Discussion

The Fabry disease (FD) is a secondary genetic disorder which is marked by a deficiency in α-galactosidase A. Diagnosis is made by analysis of the α-GAL A gene, located at Xq22, and by measurement of α-galactosidase A activity [urine, serum, tears, leukocytes, fibroblasts], which is markedly decreased in affected males and only slightly diminished in females [7]. The patient sample is limited, but consistent with the frequency the disease. The mean age at diagnosis is habitually around 30 years, and most often around one case. It is assumed that genetic investigation leads to the diagnosis of an average of 5 patients around the index case. In our series, there were 08 cases, due to consanguinity. Patients diagnosed around the index case were not asymptomatic. The clinical manifestations of our sample contrasted with the literature in that they were characterized by the low frequency of cutaneous involvement, sweating disorders and digestive manifestations [8-11]. Hearing impairment was present in 33.33% of cases. It is recognized that the rate of sudden deafness is higher in patients with FD than in the general population. Screening for hearing loss should be carried out systematically, as almost half of asymptomatic adults (46.7%] had impaired hearing attributable to FD, mainly in the higher frequencies [12].

Ophthalmological manifestations are common even in heterozygous women, as in our patients. However, not all patients display all the ophthalmological manifestations characteristic of this disease. Furthermore, women bearing the mutation are asymptomatic or have only very mild clinical manifestations, as they have only moderate α-galactosidase A deficiency. The ophthalmological manifestations typically found in Fabry disease are whorled corneas [cases 1, 2, 4 and 5], aneurysmal dilatations of the conjunctival vessels [cases 1,2,3,4,5 ,7], and obvious tortuosity of the retinal vessels. In most cases, these anomalies are found bilaterally. This is consistent with the findings of the previous studies [13-17]. With regard to neuropathic pain and acroparesthesia, women are also affected, but at an advanced age compared with men, with a tendency to spontaneous regression and yet without having expressed the febrile crisis described in two men of our series [18-21]. In Fabry disease, men with the classic form progress to renal failure around the age of 30, as in the index case, with an average age of 42 [22-24]. Renal damage is caused by the accumulation of Lyso GB3 in the endothelium and glomerular cells [25,26]. The aim of treatment is to stabilize or even attenuate renal damage [27,28].

On the cardiac aspect, two men present with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Patients with Fabry disease most often present with unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), occasionally predominant or isolated, which can perfectly mimic HCM of sarcomeric origin, a condition probably occurring up to hundred-fold more frequently in the general population [29,30]. In patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [HCM], these variants are not uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of between 0.5% in the adult population and 1.8% in men over 40 [31,32]. Treatment with agalasidase-alpha enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) has been started in four of our patients, and effectiveness will be assessed after more than six follow-up months. If treated early and at an effective dose, this therapy can slow down or even halt the disease's progression and avoid complications, thus offering patients a better quality of life. Most studies have followed up and evaluated treatment at three months, six months, twelve months, eighteen months, two years and five years [33-35].

Conclusion

Fabry disease is a scarce and potentially severe condition, with renal and cardiac complications. A simple, thorough clinical examination may suffice to make the diagnosis, but it will be systematically confirmed by a molecular study of the α-GAL A gene, which must be conducted in all family members of an affected subject. The screening of female, who are healthy carriers of the disease since transmission is X-linked recessive, is of great interest in the context of genetic counseling. Early diagnosis is crucial, and focuses on the symptomatic recognition of present or past extremity pain. Up-to-date management of patients with Fabry disease should involve the earliest possible combination of symptomatic treatment and enzyme therapy, with a preference for preventive rather than palliative treatments. One patient = one family; it is therefore essential to establish a family tree and inform family members likely to be affected/carriers of the genetic anomaly.

Conflict of interest

None

References

- Germain DP. (2010). Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 5:30.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Michaud M, Mauhin W, Belmatoug N, Garnotel R, Bedreddine N, Catros F, et al. (2020). When and how to diagnose Fabry disease in clinical practice? Am J Med Sci.

Publisher | Google Scholor - MacDermot KD. (2001). Anderson–Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 60 obligate carrier females. J Med Genet, 38:769-775.

Publisher | Google Scholor - OrtizA, Germain DP, Desnick RJ, Politei J, et al. (2018). Fabry disease revisited: management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Mol Genet Metab, 123:416-427.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Germain DP, Arad M, Burlina A, Elliott PM, et al. (2019). The effect of enzyme replacement therapy on clinical outcomes in female patients with Fabry disease –a systematic literature review by a European panel of experts. Mol Genet Metab, 126:224-35.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Feriozzi S, Hughes DA. (2020). New drugs for the treatment of Anderson–Fabry disease. J Nephrol.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Audouy D, Bord G, Chalvignac A, Levy JP. (1986). À propos d’un aspect inhabituel d’atteinte rétinienne dans la maladie de Fabry. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr, 86:731-736.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Deshayes S, et al. (2015). Pre- valence of Raynaud phenomenon and nailfold capillaroscopic abnormalities in Fabry disease: a cross-sectional study. Medicine, 94:e780.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Orteu CH, Jansen T, Lidove O, Jaussaud R, Hughes DA, Pintos-Morell G, et al. (2007). Fabry disease and the skin: data from FOS, the Fabry outcome survey. Br J Dermatol, 157:331-337

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hoffmann B. (2007). Gastrointestinal symptoms in 342 patients with Fabry disease: prevalence and response to enzyme repla- cement therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 5:1447-1453

Publisher | Google Scholor - Michaud M, Levade T, Gaches F. (2015). Évaluation des connaissances des patients atteints d’une maladie de Fabry. Rev Med Interne Suppl, 36:A30.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wanner C, et al. (2010). Prognostic indicators of renal disease progression in adults with Fabry disease: natural history data from the Fabry registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 5:2220-2228.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ortiz A, Oliveira JP, Waldek S, Warnock DG, Cianciaruso B, Wanner C, et al. (2008). Nephropathy in males and females with Fabry disease: cross-sectional descrip- tion of patients before treatment with enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 23:1600-1607.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Germain DP. (2002). Maladie de Fabry (déficit en alpha-galactosidase A) : physiopathologie, signes cliniques et aspects génétiques. J Soc Biol, 196:161-173.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lidove O, Joly D, Barbey F, Bletry O, Grunfeld JP. (2001). Maladie de Fabry chez l’adulte : aspects cliniques et thérapeutiques. Rev Med Interne, 22(S):384s-392s.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arends M, Wanner C, Hughes D, Mehta A, Oder D, et al. (2017). Characterization of classical and nonclassical Fabry disease: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol, 28:1631-1641

Publisher | Google Scholor - Germain DP, Avan P, Chassaing A, et al. (2002). Patients affected with Fabry disease have an increased incidence of progressive hearing loss and sudden deafness: an investigation of twenty-two hemizygous male patients. BMC Med Genet, 3:10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pichon M, Lidove O, Roudaire M-L, et al. (2012). Auditory and vestibular findings in Fabry disease: a study of 25 patients. Rev Med Interne, 33:364-369.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Komori M, Sakurai Y, Kojima H, et al. (2013). Long-term effect of enzyme replacement therapy with Fabry disease. Int J Otolaryngol, 282487.

Publisher | Google Scholor - M. Banikazemi, J. Bultas, S. Waldek, W.R. Wilcox, C.B. Whitley, M. et al. (2007). Fabry Disease Clinical Trial Study Group, Agalsidasebeta therapy for advanced Fabry disease, Ann. Intern. Med, 146:77-86

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arends M, Wanner C, Hughes D, Mehta A, et al. (2017). Characterization of classical and nonclassical Fabry disease: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol, 28:1631-1641.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Doheny D, Srinivasan R, Pagant S, Chen B, Yasuda M, et al. (2018). Fabry disease: prevalence of affected males and heterozygotes with pathogenic GLA mutations identified by screening renal, cardiac and stroke clinics, 1995-2017. J Med Genet, 55:261-268.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Echevarria L, Benistan K, Toussaint A, Dubourg O, Hagege AA, et al. (2016). Xchromosome inactivation in female patients with Fabry disease. Clin Genet, 89:44-54.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Friedman JM, Lyons Jones K, Carey JC. (2020). Exome sequencing and clinical diagnosis. JAMA, 324:627-628.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Germain DP, Fouilhoux A, et al. (2019). Consensus recommendations for diagnosis, management and treatment of Fabry disease in paediatric patients. Clin Genet, 96:107-117

Publisher | Google Scholor - Orssaud C, Dufier J, Germain D. (2003). Ocular manifestations in Fabry disease: a survey of 32 hemizygous male patients. Ophthalmic Genet, 24:129-139.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ortiz A, Cianciaruso B, et al. (2010). End-stage renal disease in patients with Fabry disease: natural history data from the Fabry Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 25:769-775.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Seydelmann N, Wanner C, Störk S, Ertl G, Weidemann F. (2015). Fabry disease and the heart. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab, 29:195-204.

Publisher | Google Scholor - C. Kampmann, F. Baehner, C. Whybra, et al. (2002). Cardiac manifestations of Anderson-Fabry disease in heterozygous females, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 40:1668-1674.

Publisher | Google Scholor - L. Chang, B.B. Toner, et al. (2006). Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient’s perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology, 130:1435-1446.

Publisher | Google Scholor - B. Gandek, J.E. Ware Jr. (1998). Methods for validating and norming translations of health status qu.estionnaires: The IQOLA Project approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol; 51:953-959.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ortiz A, Germain DP, Desnick RJ, et al. (2018). Fabry disease revisited: management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Mol Genet Metab, 123:416-427.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yousef Z, Elliott PM, Cecchi F, Escoubet B, Linhart A, et al. (2013). Left ventricular hypertrophy in Fabry disease: a practical approach to diagnosis. European Heart Journal, 34:802-808.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Germain DP, Elliott PM, Falissard B, Fomin VV, et al. (2019). The effect of enzyme replacement therapy on clinical outcomes in male patients with Fabry disease: a systematic literature review by a European panel of experts. Mol Genet Metab Rep, 19:100454.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Germain DP, Arad M, Burlina A, et al. (2019). The effect of enzyme replacement therapy on clinical outcomes in female patients with Fabry disease – a systematic literature review by a European panel of experts. Mol Genet Metab, 126:224-235.

Publisher | Google Scholor