Case Report

Demonstrating Evidence of Relevance, Coherence, Effectiveness, Efficiency, Impact and Resilience of Five Years’ Multisectoral Investment in Child Nutrition in Nigeria-UNICEF’s Country Programme of Cooperation (2018–2022)

- Robert Ndamobissi 1*

- Edward Eungu Kutondo 1

- Judith Hodge 2

- Nemat Hajeebhoy 1

- Mitchell Morey 3

- Hannah Ring 3

- Anna Warren 3

- Oluwaseun Ariyo 4

1UNICEF staff, Nigeria Country Office, Abuja city in Nigeria.

2International nutrition consultants for UNICEF Nigeria, resident in Beziers in France.

3American Institutes for Research (AIR), city of Arlington, VA, in USA.

4Department of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, University of Ibadan, Ibadan city Nigeria.

*Corresponding Author: Robert Ndamobissi, UNICEF staff, Nigeria Country Office, Abuja city in Nigeria.

Citation: Ndamobissi R, Kutondo E.E., Hodge J., Hajeebhoy N., Morey M., et al. (2024). Demonstrating Evidence of Relevance, Coherence, Effectiveness, Efficiency, Impact and Resilience of Five Years’ Multisectoral Investment in Child Nutrition in Nigeria-UNICEF’s Country Programme of Cooperation (2018-2022). Journal of BioMed Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 5(3):1-19. DOI: 10.59657/2837-4681.brs.24.100

Copyright: © 2024 Robert Ndamobissi, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: July 17, 2024 | Accepted: September 10, 2024 | Published: September 19, 2024

Abstract

Nigeria is the largest country in Africa in terms of its population and economy, and has innovative policies, strategies and investments to improve child survival and development. Despite these efforts, approximately 12 million Nigerian children aged under 5 years are stunted and 3 million are suffering from wasting. In response to this child malnutrition crisis, UNICEF partnered with the Government of Nigeria and public-private partners to develop and implement the Nigeria–UNICEF Country Programme of Cooperation (2018–2022), with nutrition as part of the child survival component. The Nutrition CPC was independently evaluated against six Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Assistance Committee criteria (relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability), and two cross-cutting criteria (equity/gender and resilience). Key objectives were to determine the programme’s merit based on expected results and impact; and the effectiveness of multisectoral interventions for addressing child malnutrition.

The evaluation methodology was a mixed methods’ design with two components: an impact and performance evaluation of nationwide nutrition programming; and an impact evaluation of multisectoral integrated interventions in seven pilot states. Methods included a document review, an analysis of existing survey data comparing outcomes in intervention and control states, an analysis of primary survey data from over 5,600 households, key informant interviews, focus group discussions and direct observations.

The Nutrition CPC was found to be partially successful in terms of its relevance, coherence effectiveness, efficiency (value for money), impact and equity; highly successful with regards to resilience; and ‘unsuccessful’ for sustainability. The programme achieved targets across several expected results. At the national level, it reached 35 million children with vitamin A supplementation. In UNICEF supported states, over 2.5 million (80 per cent) of children suffering from severe acute malnutrition were treated. By supporting infant and young child nutrition services, the Nutrition CPC improved the likelihood and frequency of infants receiving breastmilk (extending duration by 0.33 months per child) and a more diverse diet. However, only 30 per cent of caregivers in treatment areas were aware of the programme’s key activities and less than 20 per cent of caregivers reported receiving counselling on multisectoral interventions (water, sanitation and hygiene, child nutrition or parenting).

The programme contributed in measurable ways to improving nutrition knowledge and infant feeding practices and saving the lives of 2.5 million children aged under 5 years affected by severe acute malnutrition. However, it has not achieved its goal of significantly reducing child malnutrition, with nutrition outcomes still languishing at low levels. Prevalence of wasting has increased due to the negative impact of COVID-19 on household food insecurity, poverty and increased inflation, as well as physical insecurity in the north of the country. Delivering a multisectoral programme to support nutrition proved challenging, and many stakeholders have concerns about the government’s capacity to sustain the progress that has been achieved.

Keywords: nutrition; child malnutrition; nigeria; UNICEF; maternal & child nutrition

Introduction

Global progress has been made in reducing child undernutrition over the past few decades: however, the burden remains high, and progress has been unevenly distributed [1]. Declines in undernutrition have been particularly slow in West Africa, including in Nigeria, which has the largest number of undernourished children in Africa and the second largest in the world after India [2]. A total of 12 million Nigerian children aged under 5 years are stunted and 3 million are suffering from wasting [3]. The country accounts globally for about 10 per cent of all deaths of children aged under 5 years [4].

Nigeria has the largest population and economy in Africa [5], with a total of about 220 million people (6) and an annual gross domestic product of approximately US$448 billion. The country comprises a federation of 36 states and 1 Federal Capital Territory spread across six geopolitical zones (South-East, South-South, South-West, North-East, North-West and North-Central). Each of the 36 states is a semi-autonomous political unit, subdivided into Local Government Areas (LGAs); there are currently 774 LGAs in Nigeria. Despite being a middle-income country, 40 per cent of the country live in extreme poverty [7]. An estimated 9.3 million people, including 5.7 million children, are affected by conflicts in states in the North East, North West and North Central (Benue State) regions. Stunting prevalence among children aged under 5 years is 33 per cent at the national level, but there are wide regional disparities with the highest levels of stunting in the North West (48 per cent) and the North East (35 per cent), [8]. Family livelihoods and child nutrition are highly affected in Nigeria by the negative impact of physical insecurity (9), and the COVID-19 pandemic that resulted in huge food insecurity, inflation of food prices, household poverty, reduction of purchasing power and multiple child deprivations.

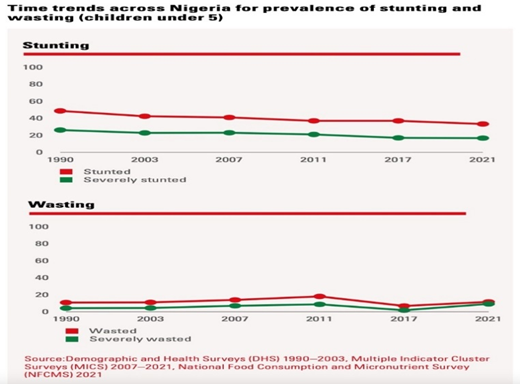

Recent improvements in undernutrition determinants in Nigeria have not resulted in considerable reductions in undernutrition: wasting prevalence halved between 2008 and 2018 and stunting declined by 9.4 per cent, but maternal undernutrition did not improve [10]. Similarly, while there were improvements in exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), vaccinations, antenatal care (ANC) and other health services, some elements such as food security and child illnesses deteriorated [10].

The country also has high levels of micronutrient deficiencies, primarily Vitamin A, iodine, iron, folic acid and zinc, but coverage rates of micronutrient supplementation and fortification remain generally low, despite their cost effectiveness. An estimated 30 per cent of Nigerian children and 20 per cent of pregnant women are Vitamin A deficient, while 76 per cent of children and 67 per cent of pregnant women are anaemic [11].

Four main factors are driving malnutrition in Nigeria, according to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2018 [11]: inadequate access to nutrition and health services; sub-optimal caring practices; a poor environment for young children and women during pregnancy; and insufficient and poor-quality food [12]. Only 34 per cent of children are exclusively breastfed and just 12 per cent consume the recommended minimum acceptable diet. Access to health services remains low and inequitable: nine out of every ten women in urban areas received ANC from a skilled provider, while only six out of every ten women received ANC from a skilled provider in rural areas [13].

Nigeria’s policy environment

Nigeria has a positive enabling environment for nutrition, reflected in current policies and guidelines such as the National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria (2016) (14); the National Multisectoral Plan of Action for Food and Nutrition (NMPFAN, 2021-2025) (15); the Micronutrient Deficiency Control Guidelines (2019); and the Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) Guidelines. The Government and its partners have also adopted the ‘one primary health-care centre (PHC) per ward’ strategy, which aims to revitalize the PHC system through establishing or rehabilitating up to 10,000 PHC centres – one in each administrative ward (16). However, evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the use of health-care services, causing further setbacks [6].

Other strategies include strengthening the National Council on Nutrition, the country’s highest decision-making body regarding food and nutrition, for better nutrition governance. At the regional level, the State Food and Nutrition Committees are important vehicles for developing costed nutrition action plans as part of framing nutrition as a multisectoral issue. Nutrition Component of the Nigeria Country Programme of Cooperation (2018–2022)

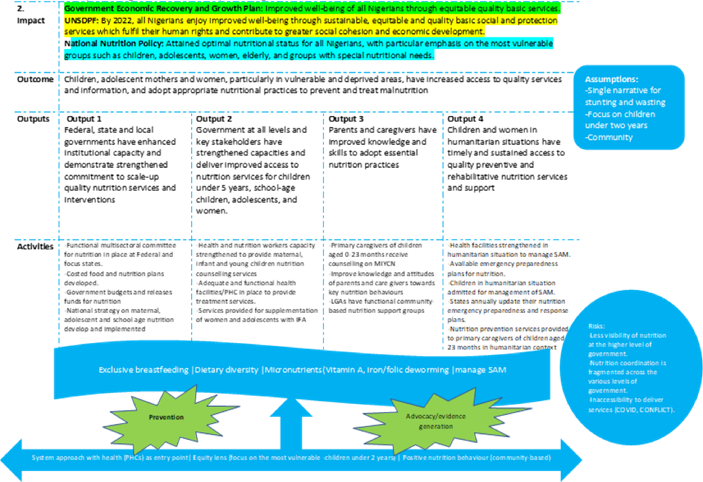

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) partnered with the Government of Nigeria and public-private institutions in the development and implementation of the Country Programme of Cooperation (CPC) 2018–2022 [16], with nutrition as part of the child survival component (hereafter, the Nutrition CPC). The programme’s main strategic outcome was to increase the access of vulnerable children, adolescent mothers and women to quality services and information for preventing and treating malnutrition. To achieve this, the Nutrition CPC worked across three inter-related areas: (i) policies and planning; (ii) service delivery and community outreach; and (iii) humanitarian relief. UNICEF focused on strengthening health and community systems and integrating nutrition into the primary health-care system, with a particular focus on community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), infant and young child feeding (IYCF) interventions and routine micronutrient supplementation.

The programme comprises four outputs:

Output 1: Federal, state and local governments have enhanced institutional capacity and demonstrate strengthened commitment to scale up quality nutrition services and interventions.

Output 2: Government at all levels and key stakeholders have strengthened capacities and deliver improved access to nutrition services for children under 5 years of age, school-age children, adolescents, and women.

Output 3: Parents and caregivers have improved knowledge and skills to adopt essential nutrition practices; and

Output 4: Children and women in humanitarian situations have timely and sustained access to quality preventive and rehabilitative nutrition services and support.

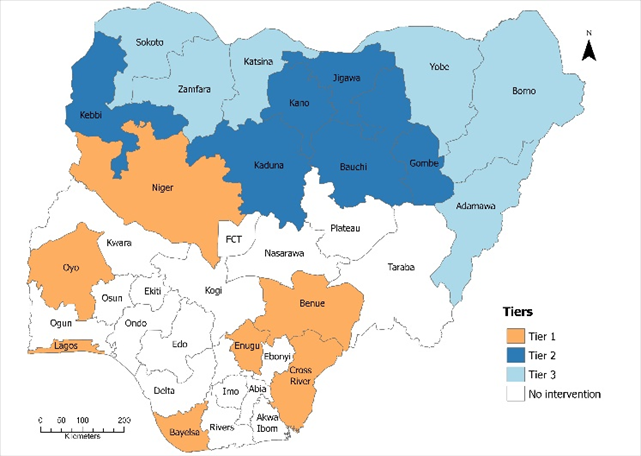

Through the Nutrition CPC (2018-2022), the Government and UNICEF committed to reducing child stunting, severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and child mortality by establishing replicable models in selected states and LGAs, and then scaling them up nationally [16]. The programme covered the whole country with varied interventions at state level; UNICEF supported targeted activities such as Vitamin A supplementation, treatment for acute malnutrition, IYCF counselling and deworming in 19 states. This targeted package was delivered in three categories or tiers within the priority states (see Figure 1).

- Tier 1 states (Bayelsa, Benue, Cross River, Enugu, Lagos, Niger and Oyo), in addition to being given the basic package, also received advocacy efforts to influence policies and realize government commitments towards nutrition.

- Tier 2 states (Bauchi, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano and Kebbi) received a full package of nutrition interventions (micronutrient supplementation), which is conducted by leveraging other sectors for complementary interventions to tackle poverty and WASH challenges.

- Tier 3 states (Adamawa, Borno, Katsina, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara) received a full package of nutrition interventions such as the provision of PHC, safe water, improved sanitation facilities and basic education, while also supporting other emergency response interventions.

Figure 1: Nutrition intervention package by state

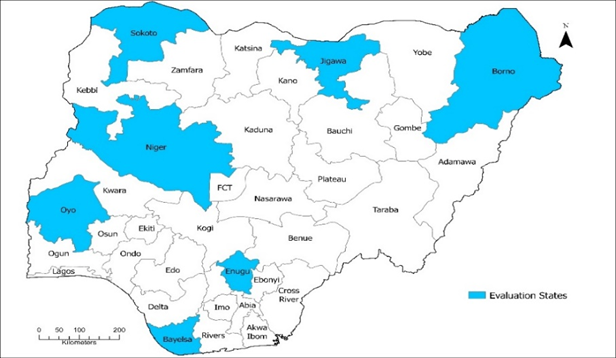

Multisectoral integrated intervention packages that combine multiple interventions, such as agriculture, child protection, livelihoods, social protection (cash transfer) and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programmes, were also implemented in seven pilot states (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Multisectoral intervention pilot states

The Nutrition CPC (2018–2022) resourced funding of US$211 million, of which nutrition in emergencies accounted for the highest expenditures (around 60 per cent) due to the dire humanitarian situation in the north of the country [17].

Methods

An independent evaluation of the Nutrition CPC (2018–2022) was commissioned in 2021 by UNICEF Nigeria and conducted by the American Institutes for Research (AIR) and Hanovia Limited. Primary objectives were to determine the merit of the programme in reducing child malnutrition in Nigeria, including the most significant drivers of the Nutrition CPC’s performance and impact, and the effectiveness of multisectoral interventions.

The evaluation had two main components: 1) an impact and performance evaluation of the overall nationwide nutrition programming; and 2) an impact evaluation [18], of the multisectoral integrated interventions pilot to evaluate the impacts of the pilot as implemented in seven states. The mixed methods used in each of the components are summarised in Table 1 below. The programme’s theory of change (see Annex 1) was used to develop the evaluation matrix, which in turn informed the specific questions and corresponding indicators that guided the evaluation.

Table 1: Summary of methods used for independent evaluation of Nutrition CPC (2018–2022).

| Methods | An impact and performance evaluation of the overall nationwide nutrition programming | An impact evaluation of the multi-sectoral integrated interventions pilot to evaluate the impacts of the pilot as implemented in seven states |

| Evaluation design | Quasi-experimental design – repeated cross-sectional generalized difference in difference (DiD) | Quasi-experimental approach –cross-sectional coarsened exact matching design |

| Evaluation criteria | OECD-DAC criteria: relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability, plus cross-cutting criteria of equity/gender and resilience | |

| Scope | The evaluation period covered 2014–2022 for purposes of accountability and learning (this Nutrition CPC phase was from 2018–2022). Primary data covered seven states: Bayelsa, Borno, Enugu, Jigawa, Niger, Oyo and Sokoto, as a representation of the 19 UNICEF-supported programme states. | |

| Sampling and sample size | Secondary data sets from Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), Nigeria Demographic and Health (NDHS) survey, and NFCMS 2021 (combined 1990-2021) | · Household survey with sample of 5,600 households |

| Purposive sample of 25 key informants was used to collect qualitative data. | · Data from 32 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), 16 Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and 8 direct observations | |

| Data collection methods | Desk review of key relevant documents; secondary quantitative data, key informant interviews at national level | Primary quantitative data and qualitative data (FGDs, in-depth interviews and direct observation at community level) |

| Data analysis method | Compared outcomes in control and treatment groups over time using “generalized difference in difference” method | Compared outcomes in control and treatment groups at one time using matching analysis |

Summary of methods applied on impact and performance evaluation of nationwide nutrition programming

- Desk review: Secondary data was used for reviewing key programme and strategy documents, reports and studies to synthesize information and findings on nutrition strategies in the country since 2018. The documents reviewed included the National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria (2016), Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) reports, the National Strategic Health Development Plan (2018–2022), the CMAM programme in Northern Nigeria and the Independent Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Impact of SDG 3: Healthy lives in Nigeria, among others.

- Sampling and sample size: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) (2007-2017) and Nigeria DHS (1990-2018) secondary data sets were used, along with qualitative data from 25 key informant interviews (KIIs).

- Data collection methods: Quantitative secondary data (from MICS 2007–2017 and Nigeria DHS 1990–2018) was leveraged to understand the overall impact of nutrition programming on key outcomes across Nigeria, without specifying the effect of any one programme. Additional qualitative data was collected from 25 KIIs based on OECD-DAC criteria (i.e., issues of programme relevance, coherence, impact etc.) to complement the quantitative data and inform nutrition strategy design and programme implementation.

- Data analysis methods: Nutrition CPC impact was established by comparing outcomes in intervention and control states, using a "generalized difference in difference” (DiD) analysis method. First, pre- and post-treatment measures were used to ‘difference’ out unmeasured, fixed (i.e., time-invariant) household or individual characteristics that may affect outcomes, e.g., characteristics such as proximity to markets, proximity to health facilities, agricultural activity in an area, pre-existing medical conditions and unobserved nutritional practices and beliefs. The evaluation team compared outcomes and impact indicators for cross-sectional cohorts of children between those exposed to UNICEF programming and those that were not. This methodology allowed the team to benchmark the change in the indicator against its value, in the absence of the programme. It also allowed them to use within-state variation to estimate impacts. Second, the team used the change in the comparison group as a counterfactual to account for general trends in the value of the outcome. For children living in control states, the outcomes and impact indicators of children who were surveyed or measured earlier (at the same time as non-exposed children in programme states) were compared with the outcomes of children who were measured later (at the same time as exposed children in programme states). The treatment states are states that had current UNICEF support through the implementation of certain programmes such as vitamin A supplementation, deworming, CMAM, IYCF counselling, micronutrient supplementation and programmes on maternal nutrition, adolescent nutrition and dietary diversification (see Figure 2). Comparison states are those states that had received some form of UNICEF support between 2017 and 2020. Descriptive statistics and trend analysis were performed.

Impact evaluation of multisectoral integrated interventions’ pilot in seven states

- Sampling and sample size: A simple random sampling method was used, with a total of 5,600 households (with a 50 per cent control group) sampled in the household survey. In each state, 800 households were selected from eligible households that had at least one child aged under five years.

- Data collection methods: A household survey was conducted between May and July 2022 in 253 enumeration areas drawn from 21 LGAs across the seven pilot states (Bayelsa, Borno, Enugu, Jigawa, Niger, Oyo and Sokoto). Quantitative data was collected on child anthropometric measurements, diet, household characteristics, as well as receipt of cash transfers and micronutrient supplementation using a holistic comprehensive questionnaire of 41 pages specially developed for this purpose (51). Qualitative data was collected from 32 FGDs, 16 KIIs and 8 direct observations, which were conducted in both urban and rural LGAs in Borno, Jigawa, Oyo and Sokoto. All data were recorded, transcribed and subjected to two quality reviews.

- Data analysis methods: A coarsened exact matching analysis method was used, since beneficiary and comparison areas can have different observable characteristics. This approach uses observable, time-invariant characteristics to find similar pairs among beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries. The statistical multi variate and regression analysis examined differences among groups and identified key findings and themes related to the evaluation questions. Qualitative data were analysed using NVivo software.

Training and pre-testing of tools

A three-day training course for data collectors was conducted, which covered ethics, data collection instruments and pre-testing. Two five-day quantitative training courses also took place in northern and southern states for 112 data collectors (14 supervisors, 84 enumerators and 14 back checkers). The training focused on anthropometry, questionnaire administration and pretesting. Feedback from the pilot test was used for improving the data collection process.

Ethical considerations

The evaluation adhered to the standards of independent, impartial and credible research, free from conflicts of interest. The contractors AIR and Hanovia followed the United Nations Evaluation Group’s Code of Conduct, which requires adherence to the four ethical principles of integrity, accountability, respect and beneficence. The ‘do no harm’ principle was applied to ensure protection of children. Ethical approval was obtained from the AIR Institutional Review Board and the National Health Research and Ethics Committee of Nigeria - NHREC/01/01/2007-10/05/2022. Informed consent was sought from respondents and data security protocols were followed.

Findings

The evaluation process drew on a wide range of qualitative and quantitative data to assess the Nutrition CPC against the OECD-DAC evaluation criteria (relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability), plus the cross-cutting criteria of equity/gender and resilience. Findings, as detailed in this section, established that most of the evaluation criteria were partially successful, apart from resilience that scored as highly successful and sustainability, which was unsuccessful (see Table 2)

Table 2: Summary of the evaluation findings

| Category of merit | Description | Criteria |

| Highly successful | All expectations are fully or nearly achieved by the programme (80-100 per cent) | Reselence |

| Partially successful | Average satisfaction (programme met 50-79 per cent of expectations) | Coherence |

| ffectiveness | ||

| Efficiency | ||

| Equity | ||

| Impact | ||

| Relevance | ||

| Unsuccessful | Expectations not met (0-49 per cent) | Sustainabilty |

Relevance

Based on qualitative information and quantitative data, results showed that the Nutrition CPC (2018– 2022) was partially relevant to the needs of beneficiaries and local communities. The programme took inequalities into account by focusing on the most vulnerable and poorest populations, especially those in rural areas, and was well aligned with government and global priorities and strategies. It was also found to be ‘doing the right thing’ in adhering to the principles of rights- and results-based planning and management in its programme design and strategic planning, using evidence from situation analysis and household survey data to identify and prioritize nutrition needs. Programme objectives to reduce stunting and wasting were relevant to beneficiary needs, with data from DHS 2018 confirming that malnutrition in children aged under 5 years is prevalent across the country, with wide variation within and between states. Programme implementers focused on regions with high nutrition deprivation and worked with varied stakeholders, such as state- and field-level staff and traditional and religious leaders, to develop plans that included: enhancing government capacity for scaling up nutrition interventions; improving access to nutrition services for women and children; improving knowledge of IYCF practices among parents and caregivers; and ensuring timely access to preventive and rehabilitative nutrition services during humanitarian situations.

The Nutrition CPC mounted a relevant response to the evolving humanitarian needs in northern Nigeria, with most programme funds directed towards interventions addressing nutrition in emergencies during the programme period (2018–2022). Adaptations to implementation approaches to reach people most in need were visible during the COVID-19 pandemic and in areas affected by flooding in 2022. However, certain preventive strategies (such as IYCF counselling) appeared inadequate because they did not fully meet beneficiaries’ needs. For example, most beneficiaries confirmed existing knowledge of healthy eating and breastfeeding practices, but constraints such as poverty and food insecurity prevented them from applying their nutrition knowledge. Beneficiaries and local stakeholders believe that poverty is the primary driver of malnutrition, suggesting that significant barriers to improving nutrition exist beyond the current scope of programming.

Any time you go to the hospital, the doctors will give you rules on what to eat and what not to eat. But with our present condition, you can’t afford to eat whatever they said you should be eating. It is unbearable for us. [Quote from mother in Jigawa State]

Coherence

The evaluation team found that the Nutrition CPC was well aligned with global-, national- and state-level policies and priorities (Ministry of Budget & National Planning, 2017), and with local priorities and contextual realities. This includes external coherence with international frameworks such as Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 to eliminate hunger and malnutrition, and consistency with national nutrition priorities and strategies in Nigeria, such as the National Policy on Food and Nutrition (2016) and the NSPAN (2021–2025). These policies were also found to cascade to state and LGA priorities. Furthermore, the programme’s strategies and activities, which focus on maternal and child nutrition and the First 1,000 Days, were aligned with UNICEF’s Global Nutrition Strategy (2020–2030) [20].

The Nutrition CPC strongly supported the urgent need for the life-saving treatment of vulnerable children suffering from SAM in the northern states affected by conflict and food insecurity, in synergy with the humanitarian actions of other nutrition stakeholders. Respondents reported close collaboration between UNICEF and relevant government ministries – the Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning, and the federal and state Ministries of Health – and Nigeria’s National Council on Nutrition and the State Food and Nutrition Committees, which enabled the leveraging of public finance and coordination of activities across multiple ministries and donors.

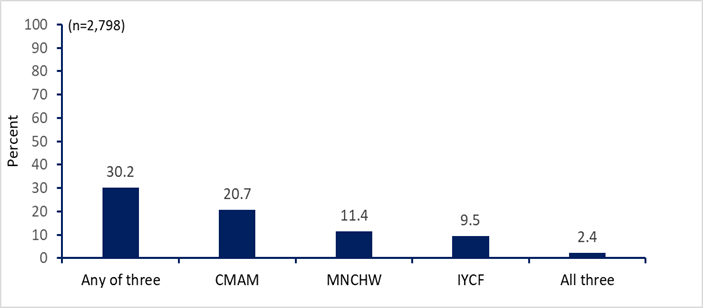

However, the evaluation concluded that the Nutrition CPC (2018–2022) was partially successful in aligning access to nutrition services. All programme activities were perceived to support the same objective (reducing malnutrition) but did not necessarily converge on the same beneficiaries. Data showed that the same households were not consistently reached with multiple CPC interventions (see Figure 3). Only 2.4 per cent of households in the CPC evaluation treatment group (n = 2,798) were aware of the three core programme components: CMAM, IYCF counselling and bi-annual national Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Weeks (MNCHW).

Figure 3: Beneficiaries’ awareness of CPC nutrition interventions

Effectiveness

Effectiveness relates to the extent to which the Nutrition CPC achieved its expected results, including any differences in results across states, in the three main strategic areas: prevention of stunting; treatment of SAM; and multisectoral integration and capacity development. The evaluation team concluded that despite some achievements in indicators for impact, outcomes and outputs, the Nutrition CPC was partially successful in achieving expected results (see Table 3).

Table 3: Nutrition CPC programme results framework/indicator status

| Impact and outcome indicators | Indicator values | Evaluative judgement by the evaluation team | ||

| Starting value (2016 baseline) | 2022 target | 2022 results | ||

| 1 Impact (government commitment 2018–2022) | ||||

| 1.1 Prevalence of stunting (%) | 37% | 20% | 33.30% | Not achieved |

| 1.2 Prevalence of underweight (%) | 20% | 15% | 25.30% | Not achieved |

| 1.3 Prevalence of wasting (%) | 7% | 5% | 11.60% | Not achieved |

| 2 Outcomes (UNICEF 2018–2022) | ||||

| 2.1 Percentage of infants aged 0–5 months who were exclusively fed with breast milk | 25% | 57% | 34% | Partially achieved |

| 2.2 Number of children aged 6–59 months who received: (i) vitamin A supplements in Semester 1; and (ii) vitamin A supplements in Semester 2 – key results for children (KR4C) indicator | 92,50,000 | 32 million | 23 million | Partially achieved |

| 2.3 Percentage of children aged 6–59 months with SAM who were admitted for treatment and recover | 88% recovery) (706,395 admitted) | 96% (363,344) | 93% (748,000) | Fully achieved |

| 2.4 Percentage of children aged 12–59 months who received: (i) deworming medication in Semester 1; and (ii) deworming medication in Semester 2 | 25% | 46% | 35% | Partially achieved |

| 2.5 Percentage of children aged 6–23 months provided with minimum acceptable diet | 25% | 21% | 11% | Not achieved |

| 3 Outputs (UNICEF 2018–2022) | ||||

| 3.1 Existence of a functional multisectoral committee for nutrition | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fully achieved |

| 3.2 Percentage of health facilities that provided treatment services for the management of SAM | 5% | 16% | 11% | Partially achieved |

| 3.3 Number of primary caregivers of children aged 0–23 months who received IYCF counselling | 6,18,050 | 13,73,186 | 12,53,080 | Partially achieved |

| 3.4 Existence of an emergency preparedness plan for nutrition | No | Yes | Yes | Fully achieved |

Source: 2022 data for stunting, underweight and wasting from Federal Government of Nigeria and International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (2022); all other figures are from National Bureau of Statistics, National Health Information System, NPC, CPC programme primary data. While trends are in the right direction, the Nutrition CPC failed to reach its targets for stunting, underweight and wasting, which are the programme’s primary outcomes. Stunting decreased from 37 per cent in 2017 (in children aged 6–59 months) to 33.3 per cent in 2021, which is far off-track from the CPC target of 20 per cent and the World Health Assembly global nutrition target of 18 per cent by 2030. Similarly, prevalence of underweight decreased from 33.4 per cent in 2017 to 25.3 per cent in 2021, failing to meet the programme target of 15 per cent. Minimum dietary diversity decreased from 40.2 per cent in 2016/17 to 31.1 per cent in 2021 and the minimum acceptable diet decreased from 25 per cent in 2016/17 to 11 per cent in 2021. In addition, the practice of early initiation of breastfeeding decreased from 42.1 per cent in 2018 to 23.1 per cent in 2021. Only 30 per cent of caregivers in treatment areas were aware of the programme’s key activities and less than 20 per cent of caregivers reported receiving counselling on child nutrition, parenting or WASH.

However, evidence from MICS data showed that the prevalence of EBF for infants aged under 6 months had increased positively from 23.7 per cent in 2016/17 to 34.4 per cent in 2021. In terms of humanitarian actions (life-saving treatment for children with SAM), the Nutrition CPC was very successful: over 2.5 million severely malnourished children aged under 5 years benefited from treatment in CMAM centres established as part of PHC services between 2018– 2022, compared to the planned five-year target of 1.2 million children.

For capacity development of institutions and communities, the Nutrition CPC supported functional multisectoral committees for nutrition in all 19 priority states, but there was mixed evidence on the quality of partnerships leveraged and the scaling up of the Nutrition CPC. The support of the government and other programme partners were important facilitators to CPC effectiveness for increasing coverage of vitamin A supplementation and other programme elements, such as distribution of deworming tablets for children and iron and folic acid for pregnant women. However, qualitative data showed that poverty and insufficient resources were notable barriers to programme success. Behaviour changes counselling appeared to be effective in increasing uptake of health-care services and healthy WASH practices, yet quantitative results did not show increased spending on children’s health care or changes to soap or latrine use. Moreover, according to evidence from the policy analysis, many LGAs lacked functional food and nutrition committees (only two LGAs had committees) and nutrition interventions concentrated at state level often failed to cascade to community level, resulting in poor coverage.

Programme effectiveness has also been undermined by changes in Nigeria’s country context in 2020–2022, such as increased insecurity and conflict that has disrupted agricultural activities, the negative effects of COVID-19 on health service delivery and spiralling inflation rates due to the national and global economic situation.

Efficiency

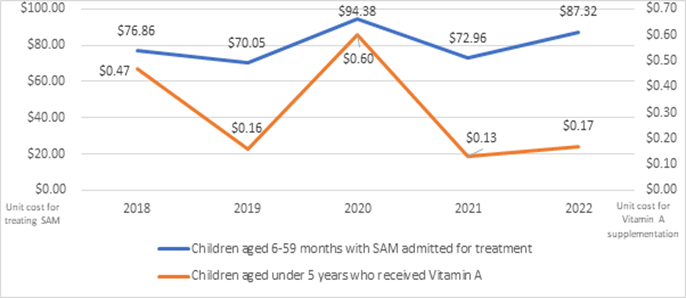

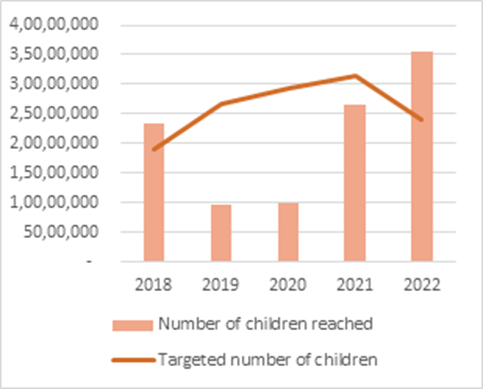

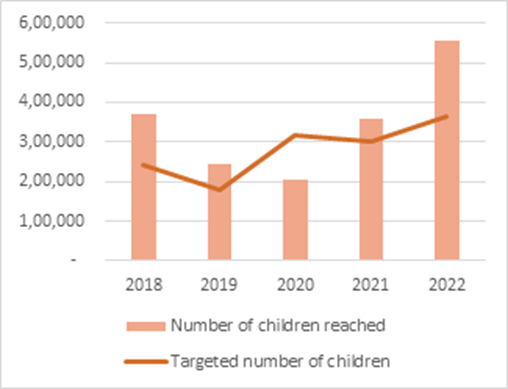

Efficiency was associated with the extent to which the nutrition programme delivered results in an economic and timely way, i.e., how well have resources been used. The evaluation team concluded that the Nutrition CPC was partially successful in realizing value for money. The programme showed cost-efficient and positive trends for children reached with vitamin A supplements and SAM treatment (see Figures 4–6). However, overall, programme efficiency was limited by its ability to reach all eligible beneficiaries in treatment areas. Only about 15 per cent of survey respondents received any of the CMAM, IYCF or MNCHW interventions.

Cost expenditure data from UNICEF and Nigeria’s state governments showed a total of US$211,440,249 reached against a planned amount of US$167,123,031 for the five-year programme cycle (2018–2022). Both parties surpassed planned expenditure for nutrition (UNICEF by 23 per cent and Nigeria’s state governments by 31 per cent), but many stakeholders claimed that the federal government’s financial commitments remain insufficient compared to the country’s nutrition needs. UNICEF allocated most of its funding to curative interventions (60 per cent to addressing nutrition in emergencies and 21 per cent to improving access to nutrition).

A cost analysis of UNICEF’s investment of US$111.3 million for local and external procurement of therapeutic commodities for life-saving SAM treatment and preventive interventions showed evidence of good value for money. Except for 2020, when the programme was disrupted by COVID-19, there were positive trends in UNICEF cost-efficiency over time, particularly for vitamin A supplementation (see Figure 5). The programme achieved better results with lower costs for both curative and preventive strategies (e.g., unit costs of US$80 for SAM treatment and US$0.30 for vitamin A supplementation), although differences in cost data reporting across different organizations limit the ability to compare cost-efficiency to external benchmarks. However, the unit cost of SAM treatment in Nigeria was comparatively lower than countries such as Ethiopia, where the unit cost of managing acute malnutrition or CMAM treatment was US$110 [21]. Furthermore, supply management of nutrition commodities appears well developed and functional, limiting stockouts of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) for children affected by SAM.

Figure 4: Unit costs of SAM treatment and Vitamin A supplementation (2018-2022).

Source: UNICEF monitoring data

Figure 5: Children aged under 5 years who received Vitamin A (2018-2022)

Source: UNICEF monitoring data

Figure 6: Children aged 6–59 months with SAM admitted for treatment (2018-2022).

Note: The costs for Vitamin A supplementation in this table correspond with UNICEF output indicator 3.2 Access to Nutrition, while the costs for SAM treatment correspond to output indicator 3.4. Nutrition in Emergencies. Some of the costs expended for these outputs have been used for some other purposes as well.

Despite such cost efficiencies, the evaluation concluded that the Nutrition CPC’s overall efficiency was limited by its ability to reach all eligible beneficiaries. Although the Nutrition CPC was made available within LGA treatment areas, only a small subset of the eligible population took advantage of programming. Higher efficiencies would have been achieved given the outlay of programme costs if the nutrition activities had reached a larger share of the population. Nevertheless, nearly 70,000 households (15.1 per cent of the total sample population in selected states) were estimated to have benefited from Nutrition CPC interventions.

Impact

The evaluation assessed the impact of the Nutrition CPC at both a nationwide level (regression comparison analysis of difference-in-differences between 19 focus states of the country programme and 18 remaining states of Nigeria) and for seven pilot states with multisectoral integrated interventions (impact estimates from difference-in-differences between selected treatment and comparison groups of LGAs within each state). The programme was partially successful with evidence showing significant programme impact on IYCF knowledge and anthropometric measures with reductions in both stunting and underweight children but not wasting. The Nutrition CPC improved the likelihood that a mother understood the importance of early initiation of breastfeeding by 4 percentage points and increased the duration of infant breastfeeding by 0.33 months. These improved behaviours carry over to child feeding; the programme increased the likelihood that children ate nutritious foods, such as tubers, vitamin A-rich foods, fish or seafood and legumes or nuts, by 2–5 percentage points. These changes may have provided the means to reduce children’s undernutrition, with the programme reducing cases of both stunted and underweight children by 3 percentage points each.

Nationwide impact indicators showed a decrease in stunting prevalence of nearly 4 percentage points from 37 per cent in 2017 to 33.3 per cent in 2021, while the prevalence of underweight decreased from 31.5 per cent in 2017 to 25.3 per cent in 2021. However, the prevalence of wasting has increased from 7 per cent in 2017, as estimated by MICS, to 11.6 per cent (see Figure 7) in 2021 [13].

Figure 7: Trends in impact indicators – prevalence of stunting and wasting in children aged under 5 years (1990-2021)

Impact findings of multisectoral integrated interventions showed that only two of the seven pilot states – Niger and Sokoto – had statistically significant differences in stunting prevalence between treatment and comparison groups (11 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively – see Table 4). Despite improvement in WASH indicators in LGAs in the treatment group in comparison to LGAs in the control group, there was little difference in stunting prevalence for children. There appeared to be no significant impact of the programme on wasting among children in any of the states (see Table 4).

Table 4: State-level comparison of key impact indicators in seven pilot states

| States | Treatment stunting | Comparison stunting | Impact | Treatment wasting | Comparison wasting | Impact |

| Borno | 43% | 46% | -1 pp | 14% | 19% | -3 pp |

| Enugu | 12% | 16% | -3 pp | 9% | 8% | 0рр |

| Jigawa | 53% | 54% | 2 pp | 22% | 18% | 4 pp |

| Niger | 25% | 34% | -11 pp*** | 13% | 13% | -3 pp |

| Sokoto | 36% | 53% | -17 pp*** | 15% | 17% | 0рр |

| Bayelsa | 18% | 15% | 2 pp | 11% | 12% | 4 pp |

| Oyo | 12% | 16% | -3 pp | 9% | 8% | 0рр |

| Overall | 30% | 34% | -3 pp** | 14% | 15% | 0рр |

| Notes: All results cover children aged 0-59 months. Impacts are in terms of percentage points (pp). Significance levels are indicated as follows: *10% significance, **5% significance, ***1% significance. | ||||||

The Nutrition CPC’s impact on improved nutrition for infants and children failed to extend to other outcomes such as child development and food security. Qualitative evidence indicated that limitations to programme impact were mainly related to food insecurity, increased inflation of food prices and household poverty – exacerbated by COVID-19 and physical insecurity.

Sustainability

The programme’s sustainability was assessed as unsatisfactory, based on the government’s perceived ‘readiness’ to continue CPC nutrition activities if UNICEF stopped its technical and financial support. Despite plans to transition programme responsibility, health workers and Ministry of Health officials expressed concerns about dependency on CPC nutrition services and the government’s ability to fund resource-intensive interventions such as CMAM.

... what might not be sustainable for a long time in the long run is the CMAM issue, because of the high cost of RUTF and the technicalities involved in, you know, administering RUTF to malnourished children.

[State-level official, Ministry of Health]

Sustainability opportunities did exist: respondents believed that some of the behaviours learned, particularly those relating to IYCF and nutrition counselling sessions, were deeply entrenched and likely to continue beyond the programme period. Yet there were also numerous challenges relating to inadequate human and financial resources, lack of political will and gaps in coordination. Programme sustainability was further undermined by environmental factors such as widespread hunger, poverty and insecurity issues.

... when we cannot access mothers ... when we start a programme, we cannot sustain that programme ... even currently, we have some LGAs, we have partners that evacuated their staff because there is an attack, so that programme cannot be sustained. [And] a child has already been enrolled, maybe that child started getting treatment and now the treatment has been interrupted, so the child will go back to malnutrition again.

[UNICEF staff member]

Equity and gender

The Nutrition CPC was assessed as partially successful in terms of equity and gender. The programme successfully targeted individuals and locations with worse nutrition outcomes, focusing on the states with the largest share of children facing undernutrition. Findings from the multisectoral pilot states confirmed that children with different levels of wealth were equally served, given consistent results from the wealthiest and poorest families. The CPC programme was also equally effective for girls and boys.

Programme implementers designed interventions with equity and gender needs in mind; and participants perceived that programming increased equity among women and girls. However, no programme impact was found for improving gender equality by empowering women in playing a larger role in household decision-making for key outcomes, such as health and feeding.

Resilience

The Government, UNICEF and partners faced serious challenges in delivering nutrition programming particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet the Nutrition CPC proved highly successful in adapting delivery modes and maintaining a level of support. In some LGAs, health and community workers adopted innovative approaches by going from house to house to provide nutrition services. Moreover, qualitative data confirmed that people continued to apply their knowledge on WASH and nutrition during this period. Only between 6 and 8 per cent of respondents who benefitted from the programme reported that COVID-19 disrupted their access to CMAM, IYCF or MNCHW activities.

As part of capacity strengthening, UNICEF supported adapting response plans to respond to various shocks, such as the 2022 floods in Nigeria. Emergency preparedness plans in five violence-affected northern states (Adamawa, Borno, Katsina, Yobe and Zamfara) were updated annually during the programme period. Despite increased levels of conflict in Borno, Niger and Sokoto states, UNICEF mobilized funding, enhanced partnerships with NGOs and adapted programming for ensuring the continued delivery of life-saving treatment for 2.5 million children suffering from SAM.

Discussion

The Nutrition CPC (2018–2022) was identified as an important programme in addressing the high burden of child malnutrition in Nigeria; and was well aligned with key nutrition policies such as the NMPFAN. The programme was relevant in addressing pressing needs arising from the humanitarian situation in Northern Nigeria. However, beneficiaries found preventive strategies such as IYCF counselling less relevant to their needs, identifying poverty and food insecurity as the main barriers to achieving optimal feeding practices. A parallel Key Results for Children evaluation (22) also found that lack of access to diverse and micronutrient-rich foods was a key challenge for caregivers in Nigeria; and other researchers report that Nigeria’s chief barrier to improved nutrition is poor diet quality [23].

Yet Mahumud et al’s [24] meta-analysis confirms the relevance of social and behaviour change communication as an important strategy in improving child nutritional status within the First 1,000 Days, including EBF and child anthropometric outcomes. Using DHS survey data, Fadare et al (25) concluded that mothers’ knowledge of health and nutrition was positively associated with child wasting and stunting in rural Nigeria.

Although EBF in Nigeria increased from 20 per cent in 2003 to 31 per cent in 2018 [10], the country still lags behind global EBF rates of 40 per cent, signalling the continued relevance of IYCF counselling. Nearly 70 per cent of countries have high rates of continued breastfeeding at one year, compared to 28.7 per cent in Nigeria [22]. Nutrition CPC evaluation respondents may have indicated existing knowledge of IYCF practices, but barriers to converting that knowledge into practice remain an area of concern (for example, the continued practice of giving water as well as breastmilk – 16). A study of four Sahel and Horn of Africa countries with similar stubborn high levels of stunting and wasting (Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Niger and Senegal) confirmed that negative social norms and cultural beliefs cause inadequate child feeding, nutrition and health care practices that facilitate disease and malnutrition [25].

Moreover, research confirms wide sub-national variations in both breastfeeding practices and other determinants for child malnutrition in Nigeria, which correlated to higher stunting rates in emergency-affected northern states compared to southern states (27; 2828). A national programme to address child undernutrition needs to account for strong geographical differences and develop relevant solutions for addressing stunting in northern Nigeria (29). There is still inadequate research around how to implement already identified interventions, as well as how to identify new and/or multisectoral interventions that can address the gaps in nutrition outcomes in Nigeria, vis-à-vis the context of different states and LGAs [28].

Unequal progress in addressing key global nutrition challenges in children aged under 5 years both within and across countries is attributed to several factors, including lack of coherence and coordination across different sectors [30]. A policy coherence analysis found that Nigeria’s recent investment in institutional transformations had galvanized aligning actions around common results, including tracking resource mobilization for nutrition [30]. This is in line with the Nutrition CPC evaluation’s findings of strong collaboration between UNICEF and the Ministry of Finance, Budget and Planning, enabling coordination of activities across multiple ministries and donors.

Yet more needs to be done to ensure that national nutrition priorities, as elaborated in policy documents, are reflected at the programme level. The Nutrition CPC showed low internal coherence, with 2.6 per cent of households in the evaluation treatment group being aware of core CPC components. Better nutrition outcomes are consistently seen in programmes that deliver cross-sectoral interventions or combine multiple delivery platforms (31). ‘Co-location’ of sectoral programmes to reach the same communities and households may offer a more pragmatic strategy than the tight sector alignment, coordination and monitoring required for implementing fully integrated programmes [31].

CMAM programmes have proven effective in helping admitted children to recover from SAM and promoting prevention through community outreach and MAM management. Results of a 2012 CMAM evaluation in Ethiopia funded by UNICEF showed improved access and coverage as the number of SAM children treated annually increased from 18,000 in 2002 to 230,000 in 2012—more than 12-fold in a decade [32]. The Nutrition CPC in Nigeria was highly effective in achieving outputs related to SAM treatment, via CMAM programmes integrated into primary health-care services. Similarly, multisectoral collaboration between health and nutrition sectors enabled successful scaling up of Vitamin A supplementation. Integrated routine and COVID-19 vaccines, Vitamin A and birth registration campaigns were conducted in 33 states reaching 35 million children in 2022 in semester one [33].

The Nutrition CPC was less effective in reaching its stunting and wasting targets, which is unsurprising given the low awareness (30 per cent) and low coverage (20 per cent) of the programme’s key activities. This aligns with other research showing nutrition intervention coverage in Nigeria to be low compared to the magnitude of need. Despite scale-up and improvements in the MNCHW package (from 2008-2019), coverage of most interventions was below 50 per cent in the target population, too low to be effective (15). Intra-sectoral and multisectoral coordination were also potentially inadequate; Adeyemi et al. (10) showed that 12 per cent of children had received all three selected health sector interventions and 6 per cent had received six selected multisectoral interventions for stunting reduction in Nigeria between 2008–2019. Achieving and sustaining high coverage of effective multisectoral interventions remain the critical limiting factors for reducing malnutrition (31;34).

The programme achieved some success in numbers reached and cost efficiencies for vitamin A supplements and SAM treatment. Njuguna et al’s 2018 systematic review [35] found CMAM’s integration of outpatient and inpatient care of undernourished children to be cost-effective, although there is a need for programmes to address issues of cost that may limit delivery, uptake and effectiveness (e.g., time spent away from normal duties caring for a sick child or attending clinics).

The Nutrition CPC’s efficiency was also limited by low programme reach; Abdulahi et al [36] recommend that multisectoral nutrition programmes explore integration into routine services for economies of scale to lower costs. The Government of Nigeria has invested in some key nutrition-sensitive sectors, especially agriculture, health, education and WASH, but these remain inadequate and have low impact due to Nigeria’s large population.

The evaluation did not detect programme impacts on food security and food consumption, but it did positively impact stunting through improved IYCF practices in the multisectoral integrated pilot in seven states (with results mainly driven by two states, Niger and Sokoto). However, there was no significant impact of the programme on wasting among children in any of the states; in fact, the evaluation found a drastic increase of wasting prevalence from 7 per cent in 2017 to 11.6 per cent in 2021, revealing the negative impact of COVID-19 on the nutritional status of children aged under 5 years in Nigeria. This finding chimes with Headey et al’s [37] predictions of COVID-19’s unprecedented global social and economic impact on child malnutrition, including wasting, due to steep declines in household incomes, changes in the availability and affordability of nutritious foods and interruptions to health, nutrition and social protection services. The impact of COVID-19, particularly fatalities, has been especially acute in countries with a high burden of population-level malnutrition such as those in the Sahel strip (northern Nigeria is part of the Sahel region) [38].

Nigeria is one of the 15 countries most severely affected by the current global food and nutrition crisis, in which only one in three children with severe wasting receive treatment [39]. Food and nutrition security in Nigeria were also impacted during the 2008-2010 global economic crisis, with food price increases affecting nearly every agricultural product in Nigeria without a corresponding increase in the disposable income of families and population groups (especially vulnerable groups) [40]. Programmes such as the Nutrition CPC must address the determinants and drivers of undernutrition to have an impact on the more life-threatening forms of child wasting. This includes joint intervention packages for both wasting and stunting that overcome the humanitarian-development divide, and aim to secure substantial, sustainable and predictable funding [41].

Programme sustainability was considered a major issue for the Nutrition CPC. Even when costed plans exist, expenditure data showed that development partners spent over three times as much on nutrition programming in 2019 than Nigeria’s federal government. This is in line with a World Bank assessment of six African countries’ funding gaps for nutrition-specific costed plans for 2015–2017: Nigeria had the lowest levels of domestic and donor resources, with a year-on-year fall in spending [42]. This situation is unlikely to improve in the current global crisis and the devastating impacts of the country’s current conflicts and economic recession. A recent IFPRI report on Nigeria’s food system sustainability confirms the huge financing gap between emergency assistance, which has increased in recent years, and the significant underfunding of longer-term investment needed to achieve SDG2 and build resilience against future shocks [43]. Nigeria has come a long way from having little commitment for nutrition in the early 2000s, but sustaining momentum for addressing child malnutrition is challenged by limited multisectoral coordination, limited technical skills among policymakers, inadequate numbers of frontline workers and financial resource shortfalls [28]. Greater advocacy efforts are needed to ensure that funds allocated for nutrition are released.

The programme’s strategic approach was aligned with equity and gender policies. Analysis of Nigeria’s DHS data confirms the importance of addressing the socioeconomic inequalities that determine child stunting and wasting, especially wealth, maternal education and access to sanitation [44]. Other studies highlight the key role of gender in nutrition. Sawalu et al (45) found that women’s empowerment significantly increased household dietary diversity in rural Nigeria, thereby reducing the probability of child stunting. Yet significant gender gaps exist in the country (Nigeria ranked 128 out of 158 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index in 2020), with the highest gender inequality in the North West. Gender-related barriers such as female roles and lack of agency are present in most nutrition programmes, and likely to affect coverage (46). The Nutrition CPC could be further strengthened by applying gender transformative approaches that move away from burdening women with the responsibility for equality and engage men and women together in behavioural change activities [46;47]. Projects working with religious and community leaders in Kaduna State, Northern Nigeria were successful in engaging fathers to improve dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months [48].

Finally, the Nutrition CPC showed itself to be resilient in the face of such challenges as COVID-19. Programmatic adaptations such as Family-led mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) and modified dosage of therapeutic foods enabled service continuity in Nigeria, in line with research findings from 17 other countries [49].

Limitations

There were several limitations noted in the evaluation’s different methods. The key limitation to the DID approach is the assumption that there are no systematic, unobserved, time-varying differences between the treatment and comparison states. For example, if the comparison states independently invest in reducing malnutrition but the treatment group does not, then the impact of UNICEF programming would be underestimated rather than attributing the comparison group’s improved nutritional outcomes to this unobserved, time-varying change in spending. In practice, the large, representative number of states that are included in the sample and the repeated outcome measures from multiple rounds of extant data should minimize the average trend differences. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the programme states had pre-existing, differing trends that could bias the evaluation’s impacts.

Furthermore, the coarsened exact matching analysis method requires a large sample to accurately estimate the impact of the programme. This method is less efficient than a randomized process in which the treatment group is a good match for the comparison group on average, although necessary given the ex-post nature of the evaluation.

Conclusion

The comprehensive and independent evaluation of Nigeria’s Nutrition CPC made important findings on which aspects of the programme were successful and where there were opportunities for improving the next programme phase. The Nutrition CPC achieved targets across a number of expected results, providing vital support that directly benefited newborn and young children aged 0–59 months during the First 1,000 Days of Life. At national level this included reaching 35 million children with vitamin A supplementation, and over 2.5 million (80 per cent) of children suffering from SAM were treated in UNICEF-supported states. By supporting IYCF services, the programme improved the likelihood and frequency of infants receiving breastmilk (extending duration by 0.33 months per child) and a more diverse diet.

However, only 30 per cent of caregivers in treatment areas were aware of the programme’s key activities and less than 20 per cent of caregivers reported receiving counselling on multisectoral interventions (WASH, child nutrition or parenting). The programme has not achieved its goal of a significant reduction in child malnutrition, with nutrition outcomes still languishing at low levels. Furthermore, delivering a multisectoral programme to support nutrition has proved challenging, and many stakeholders have concerns about the government’s capacity to sustain progress that has been made.

Undernutrition (stunting, wasting and underweight) remains high in Nigeria and requires continued (and increased) investment. An evaluation of the country’s likelihood for achieving its SDG targets for child mortality and stunting reduction found that Nigeria was off-track [50]. The main drivers were the very low level of public health financing (4 per cent of GDP, the lowest in Africa), limited access, poor quality and weak local governance of PHCs, huge household out-of-pocket payment for health services and poverty. Numerous other factors such as COVID-19, increased food prices, insecurity and climate change aggravated household poverty and child vulnerabilities to malnutrition during the programme time period (2018-2022). Key lessons learned are that nutrition programming that does not also address these underlying drivers of malnutrition may handicap the ability of stakeholders (government – federal and state, donors and communities) to accelerate improvements in reducing child malnutrition in Nigeria.

List of abbreviations

AIR: American Institutes for Research; ANC: Antenatal Care; CMAM: Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition; CPC: Country Programme of Cooperation; DiD: Difference in Difference; EBF: Exclusive Breastfeeding; FGD: Focus Group Discussion; IMAM: Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition; IYCF: Infant and Young Child Feeding; KII: Key Informant Interview; LGAs: Local Government Areas; MAM: Moderate Acute Malnutrition; MICS: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; MNCHW: Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Weeks; MUAC: Mid‐Upper Arm Circumference; NDHS: Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey; NGO: Non-governmental Organization; NMPFAN: National Multisectoral Plan of Action for Food and Nutrition; OECD DAC: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee; PHC: Primary Health Care; RUTF: Ready-to-use Therapeutic Food; SAM: Severe Acute Malnutrition; SDG: Sustainable Development Goal; WASH: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene.

Supplementary information

Annexe 1: Theory of Change for the Nutrition Programme in Nigeria

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the strong support provided by the state authorities for Health, Nutrition, Planning, Security, etc. and for the local authorities for their key facilitation roles that they played in ensuring the operationalization of field data collection in a challenging context.

We recognise the crucial key role played by Hanovia Limited, the local consortia for research and studies who undertook high-quality field data collection. We particularly thank Sandra Amoh and ‘Gbenga Adeyayo for their skilled project administration and multiple enumerators who ably collected the data for this evaluation.

Funding

The Evaluation was funded by UNICEF Nigeria Country Office using regular resources.

Declarations (ethics approval and consent to participate)

As co-authors, we declare collectively that this article represents a free access publication that is open to all researchers, decision and policy makers, private sector and academia, and all nutrition stakeholders for the purpose of providing sound evidence and knowledge to accelerate the achievement of the global SDG2 agenda ending hunger and reduction of child malnutrition for all children in Nigeria and globally. There is no conflict of interest with this article.

References

- Black, R. E., Allen, L. H., Bhutta, Z. A., Caulfield, L. E., De Onis, M., Ezzati, M., ... & Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. (2008). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet, 371(9608):243-260.

Publisher | Google Scholor - United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization, & World Bank Group. (2020). Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2020 edition of the joint child malnutrition estimates. New York, Geneva, & Washington, D.C. UNICEF, WHO, & World Bank.

Publisher | Google Scholor - United Nations Children’s Fund. (n.d.). Nutrition: Malnutrition rates in children under 5 years.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Population Commission & CIRCLE, Social Solutions, Inc. (2020). Nigeria 2019 Verbal and Social Autopsy Study: Main Report.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hinshaw, D., & McGroarty, P. (2014). Nigeria’s economy surpasses South Africa’s in size. The Wall Street Journal.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Federal Government of Nigeria, Office of the Senior Special Assistant to the President on Sustainable Development Goals, & UNICEF. (2022). Healthy Lives in Nigeria: Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Impact of SDG3. OSSAP-SDGs & UNICEF, Abuja, Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Poverty in Nigeria, 2019: Measurements and Estimates.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Federal Government of Nigeria & International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. (2022). National Food Consumption and Micronutrient Survey 2021: Preliminary report. Abuja & Ibadan: FGN & IITA.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Howell, E., Waldmann, T., Birdsall, N., Holla, N., & Jiang, K. (2020). The impact of civil conflict on infant and child malnutrition, Nigeria, 2013. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 16(3):e12968.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adeyemi, O., van den Bold, M., Nisbett, N., & Covic, N. (2023). Changes in Nigeria’s enabling environment for nutrition from 2008 to 2019 and challenges for reducing malnutrition. Food Security, 15(2):343-361.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Population Commission & ICF International. (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, 2018. Abuja & Rockville, Maryland: NPC & ICF International.

Publisher | Google Scholor - ACF International. (2015). Severe acute malnutrition management in Nigeria: Challenges, lessons, and road ahead.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Bureau of Statistics & United Nations Children’s Fund. (2022). 2021 Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey and National Immunization Coverage Survey: Statistical snapshots. Abuja: NBS & UNICEF.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning. (2016). National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning. (2020). National Multi-Sectoral Plan of Action for Food and Nutrition 2021–2025. Federal Government of Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - UNICEF. (2017). Country programme document, Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ige, M. (2019). Exposure to negative shocks and child development: Evidence from Boko Haram attacks. Texas A&M University, Department of Economics.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Publisher | Google Scholor - United Nations Children’s Fund. (2020). Nutrition, for Every Child: UNICEF Nutrition Strategy 2020–2030. New York: UNICEF.

Publisher | Google Scholor - United Nations Children’s Fund, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, & International Food Policy Research Institute. (2020). Impact evaluation of improved nutrition through integrated basic social services and social cash transfer pilot program (IN-SCT) in Oromia and SNNP regions, Ethiopia: Endline impact evaluation report. Addis Ababa: UNICEF Ethiopia, IFPRI, & MoLSA.

Publisher | Google Scholor - UNICEF West & Central African Regional Office. (2022). UNICEF Nigeria Country Office and KIT Tropical Institute: Formative evaluation of acceleration strategies for achieving Key Results for Children # 2 (prevention of stunting) in Nigeria during the period 2018-2020. Senegal, Dakar: UNICEF West & Central African Regional Office.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ecker, O., Comstock, A., Babatunde, R. O., & Andam, K. S. (2020). Poor dietary quality is Nigeria’s key nutrition problem: Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security policy research brief 119. Michigan State University.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mahumud, R. A., Uprety, S., Wali, N., Renzaho, A. M., & Chitekwe, S. (2022). The effectiveness of interventions on nutrition social behaviour change communication in improving child nutritional status within the first 1000 days: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18:e13286.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fadare, O., Amare, M., Mavrotas, G., Akerele, D., & Ogunniyi, A. (2019). Mother’s nutrition-related knowledge and child nutrition outcomes: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. PLoS ONE, 14(2):e0212775.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ndamobissi, R. (2018). Child malnutrition in Sahelian and Horn of African countries: Sociodemographic and political challenges (Burkina Faso, Niger, Senegal, Ethiopia, Ghana). Paris, France: Harmattan.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akombi, B., Agho, K. E., Hall, J. J., Merom, D., Astell-Burt, T., & Renzaho, A. M. (2017). Stunting and severe stunting among children under-5 years in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatrics, 17(1):1–16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adeyemi, O., Toure, M., Covic, N., van den Bold, M., Nisbett, N., & Headey, D. (2022). Understanding drivers of stunting reduction in Nigeria from 2003 to 2018: A regression analysis. Food Security, 14(4):995-1011.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Amare, M., Benson, T., Fadare, O., & Oyeyemi, M. (2018). Study of the determinants of chronic malnutrition in Northern Nigeria: Quantitative evidence from the Nigeria demographic and health surveys. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 39(2):296-314.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Billings, L., Pradeilles, R., Gillespie, S., Vanderkooy, A., Diatta, D., Toure, M., Diatta, A. D., & Verstraeten, R. (2021). Coherence for nutrition: Insights from nutrition-relevant policies and programmes in Burkina Faso and Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning, 36(10):1574-1592.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Heidkamp, R. A., Piwoz, E., Gillespie, S., Keats, E. C., D’Alimonte, M. R., et al. (2021). Maternal and child undernutrition progress 2: Mobilising evidence, data, and resources to achieve global maternal and child undernutrition targets and the Sustainable Development Goals: An agenda for action.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alebachew, A., & Reed, S. (2012). Evaluation of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: International Consulting PLC (BIC).

Publisher | Google Scholor - United Nations Children’s Fund Nigeria. (2021). Country Office annual report 2021.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gillespie, S., Haddad, L., Mannar, V., Menon, P., & Nisbett, N. (2013). The politics of reducing malnutrition: Building commitment and accelerating progress. The Lancet, 382(9891):552-569.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Njuguna, R. G., Berkley, J. A., & Jemutai, J. (2020). Cost and cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment for child undernutrition in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Wellcome Open Research, 3(5):62.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Abdullahi, L. H., Rithaa, G. K., Muthomi, B., Kyallo, F., Ngina, C., Hassan, M. A., & Farah, M. A. (2021). Best practices and opportunities for integrating nutrition-specific into nutrition-sensitive interventions in fragile contexts: A systematic review. BMC Nutrition, 7(1):1-17.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Headey, D., Heidkamp, R., Osendarp, S., Ruel, M., Scott, N., et al. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. The Lancet, 396(10250): 519-521.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mertens, E., & Peñalvo, J. L. (2021). The burden of malnutrition and fatal COVID-19: A global burden of disease analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7:351.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Global Action Plan on Child Wasting. (2022). A framework for action to accelerate progress in preventing and managing child wasting and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elijah, O. A. (2010). Global food price increases and nutritional status of Nigerians: The determinants, coping strategies, policy responses, and implications. ARPN Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science, 5(2):67-80.

Publisher | Google Scholor - UNICEF. (n.d.). Child wasting policy brief: West and Central Africa.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Horton, S. E., Brooks, J. K., Mahal, A. S., McDonald, C., & Shekar, M. (n.d.). Scaling up nutrition: What will it cost? Directions in Development: Human Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ceres. (2022). Annual report: Deep dive.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nwosu, C. O., & Ataguba, J. E.-O. (2020). Explaining changes in wealth inequalities in child health: The case of stunting and wasting in Nigeria. PLoS ONE, 15(9):e0238191.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Salawu, M. B., Rufai, A. M., Salman, K. K., & Ogunniyi, I. A. (2022). The influence of women empowerment on child nutrition in rural Nigeria: Research paper.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zuza, I., Bernabé, B. P., Ituero, C., Kumar, S., Woodhead, S., et al. (2017). Gender-related barriers to service access and uptake in nutrition programmes identified during coverage assessments. World Nutrition, 8(2):251-260.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wong, F., Vos, A., Pyburn, R., & Newton, J. (2019). Implementing gender transformative approaches in agriculture. CGIAR Collaborative Platform for Gender Research.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Martin, S., Allotey, D., Ipadeola, A., Kwasu, S., Mikail, A., Nyaku, A., Bose, S., Imam, R., Kalluru, K., Worku, B., & Flax, V. (2021). Engaging fathers to improve dietary diversity in Northern Nigeria: Perspectives from community and religious leaders, community health extension workers, and parents. Current Developments in Nutrition, 5(2):665-665.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wrabel, M., Stokes-Walters, R., King, S., Funnell, G., & Stobaugh, H. (2022). Programmatic adaptations to acute malnutrition screening and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18(4):e13406.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ndamobissi, R., Castrilo, M., & Yusuf-Yunusi, B. (2022). Evidence of challenging progress towards achieving the Global Agenda 2030 (SDG3) of Healthy Lives in Nigeria. Abuja, Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - UNICEF & AIR. (2022). UNICEF Nigeria 2018-2022 nutrition country programme evaluation quantitative survey: Final household questionnaire. UNICEF & AIR. March 2022, Abuja, Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor