Research Article

Current Status of Ethnobiology in North Macedonia

- Besnik Rexhepi *

University of Tetova, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Department of Biology, Tetovo, North Macedonia.

*Corresponding Author: Besnik Rexhepi,University of Tetova, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Department of Biology, Tetovo, North Macedonia.

Citation: Rexhepi B. (2025). Current Status of Ethnobiology in North Macedonia. International Journal of Nutrition Research and Health, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 4(1):1-10. DOI: 10.59657/2871-6021.brs.25.040

Copyright: © 2025 Besnik Rexhepi, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 07, 2025 | Accepted: March 13, 2025 | Published: March 22, 2025

Abstract

Background: North Macedonia is a country rich in both bio-cultural and biodiversity. However, the status of ethnobiology in many regions of the country remains virgin. While ethnobiological research is very popular in other parts of the Balkan Peninsula, there is a lack of information on how the field has developed in North Macedonia.

Methods: We analyzed publications indexed in Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from 1800 to 2024, using key terms ethnobiology and subfields such as ethnobotany, ethnoecology, ethnoscience, ethnomycology, ethnozoology, biocultural studies Socio-ecology and the former and current names of North Macedonia. The number of publications was compared against the country’s linguistic and cultural diversity, including elements of surface and deep culture of the cultural iceberg (language, functional food, gender roles, religion, etc.). To understand the focus of the research, the data was categorized into the five phases of ethnobiology and compared with neighboring countries.

Results and conclusions: A limited number of publications on ethnobiology and subfields were recorded for North Macedonia [16], indicating a significant research gap despite the country’s rich biocultural diversity. Initial results suggest that much of the research is in early exploratory phases, with limited attention to ethnoecological and ethnomycological studies. Not surprisingly, comparisons with other neighboring countries such are Croatia, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Albania, and Bosnia and Herzegovina require more attention. Taken together, the findings of previous studies highlight the need for further research in all subfields but also their conservation, socio-ecological, and cultural importance.

Keywords: biocultural diversity; ethnobiology; north Macedonia; five phases

Introduction

A closer examination of early ethnobiological studies, such as those conducted by Robbins et al. (1916) and Jones (1941), reveals that the pioneers of ethnobiology recognized the value of local knowledge about plants and animals from various perspectives. In this regard, the field was appreciated not only for its scientific contribution but also for its role in understanding the cultural, ecological, and practical significance of this knowledge. True to its name and a research ethics dominated by colonial principles, early ethnobotanical research primarily examined the relationship between ethnic communities and plants. In this respect Castetter (1944) broadened the scope with the term “ethnobiology” to signify the use of plants and animals by so-called “primitive” people Castetter (1944). Today, ethnobiology has evolved into a multifaceted discipline, encompassing ethnobotany, ethnozoology, ethnoecology, ethnopharmacology, ethnomedicine, ethnomycology, and ethnoveterinary, each of which explores different intersections of human interaction with nature Conklin (1954).

The history of ethnobotany traces back to ancient civilizations, where humans documented their interactions with plants for food, medicine, and rituals (Silva et al., 2014). Early examples include texts like those of Dioscorides, which cataloged medicinal plants and their uses Beck (2005). The formal term "ethnobotany" was introduced by John W. Harshberger in 1895, though its roots extend to earlier studies of indigenous knowledge by colonial botanists and anthropologists such as Stephen Powers (1840-1904). While global ethnobiology emerged in the context of ancient traditions, including those of Greece and Egypt (Bala, 1985; Žuškin et al., 2008) the historical trajectory of North Macedonia also reflects deep-rooted connections between human communities and biodiversity. Ancient medicinal systems, such as those documented in traditional Balkan practices, highlight the significance of folk knowledge as a precursor to formalized medicinal systems Svanberg et al., 2011.

The phases of ethnobiology, as described by Clement (1998) and expanded upon by Hunn (2007), offer a framework for understanding its evolution. For North Macedonia, these phases align with a shift from documentation of traditional knowledge toward interdisciplinary collaborations. The region is now poised to enter what Wolverton (2013) described as "Phase 5," where ethnobiology addresses contemporary environmental and cultural crises. This necessitates an inclusive approach that integrates traditional knowledge with modern scientific methods, ensuring community participation and sustainable management of biodiversity. Ethnobiological research in North Macedonia must also grapple with global concerns such as intellectual property rights (IPR) and prior informed consent (PIC), which were institutionalized in the 1992 by the International Society of Ethnobiology in the Code of Ethics (ISE, 2006).

Biocultural diversity (BCD), a concept linking cultural and biological diversity, has gained traction as a framework for sustainable development and conservation in regions like North Macedonia (Damo, Icka & Ismaili, 2012). Despite its biodiversity and cultural richness, North Macedonia lacks comprehensive ethnobiological studies compared to other Southeast European regions. This gap underscores the need for focused research documenting traditional ecological knowledge and its contemporary relevance. By integrating ethnobiology into national conservation strategies and fostering collaboration among linguists, anthropologists, and ecologists, North Macedonia can emerge as a vital contributor to global ethnobiological discourse. The socio-cultural and ecological richness of North Macedonia offers a unique perspective within the Balkan Peninsula. Its rich flora, fauna, and cultural heritage place it at the crossroads of Mediterranean and continental biodiversity (Svanberg et al., 2011). However, much of North Macedonia’s traditional ecological knowledge remains undocumented or poorly integrated into modern ethnobiological research (Žuškin et al., 2008). The regional practices documented in ethnobotanical compilations, such as those related to mountain herbs like Sideritis scardica Griseb. (Mountain Tea), reflect the broader biocultural significance of the area, connecting the tangible natural environment with intangible cultural traditions (Rexhepi & Abdija, 2025 in press).

Methodology

This study is inspired by the article Ethnobiology, Political Ecology, and Conservation, published in the Journal of Ethnobiology by Wolverton, S., Nolan, J. M., & Ahmed, W. (2014). The article highlights the interconnectedness of ethnobiology with other subfields. Publications indexed in the Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases for the period 1800 to 2024 per each phase were identified using "North Macedonia" "Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” and its historic name "Republic of Macedonia" in combination with various disciplines of ethnobiology as keywords. As North Macedonia has undergone historical and political changes, it was essential to account for publications using earlier references to the region. Key ethnobiological disciplines included in our analysis were ethnobotany, ethnoecology, ethnoscience, ethnomycology, ethnozoology, and biocultural studies. Socio-ecology was included to highlight the role of traditional knowledge in shaping human-environment interactions, which are crucial in the local economic context.

We utilized Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases due to their reliability and breadth, as recommended by studies comparing major academic databases. Studies were considered ethnobiological if they explored human-nature interactions, excluding those purely pharmacological. Extracted data included year of publication, study focus (e.g., ethnobotany, ethnomedicine), and international collaborations. Publications were categorized into five phases of ethnobiological research:

Table 1: Phases of ethnobiology (Hunn 2007; Wyndham et al., 2011)

| Phase | Time | Focus | Characteristics |

| Phase I | 1800-1950 | Documentation and Description | Emphasis on cataloging plant and animal use; descriptive accounts of indigenous knowledge |

| Phase II | The 1950s forward | Ethnoscience: Cognition | Exploration of cognitive systems; focus on classification, naming, and local knowledge frameworks. |

| Phase III | The 1970s forward | Ethnoecology: TEK and related arenas | Integration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK); understanding human-nature interactions and ecosystems. |

| Phase IV | The 1980s forward | Indigenous Ethnobiology: Power Relation | Recognition of indigenous rights, power dynamics, and community-based participatory research. |

| Phase V | 2010s forward | Interdisciplinarity and Application | Application-oriented studies, addressing biocultural conservation, sustainability, and socio-ecological challenges. |

Finally, the research output was compared against the number of recognized ethnic groups, languages, and traditional ecological knowledge systems in North Macedonia to evaluate the scope and trends in ethnobiological research for the region.

Results And Discussion

Ethnobiology in North Macedonia - Analysis

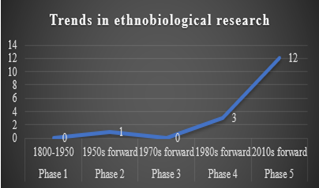

Our query returned more than 82 publications for the period of 1800-2024, from which a total of 17 publications were selected based on the pre-defined criteria for North Macedonia. Of these 17 publications, at least four resulted from international collaborations. The data shows that the number of annual ethnobiological publications has grown gradually from only three in 1984, 1996, and 2007 to 12 publications in 2010–2024; one publication was recorded in the databases for the period of [1800–1969]. Figure [1] provides a quick overview of the increasing number of ethnobiology publications over time.

Figure 1: Trends in ethnobiological research across each phase according to Hunn (2007)

Based on our analysis of Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases, ethnobotanical research in North Macedonia truly commenced in 2013, when the first study in the country was published in the prestigious Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine by Andrea Pieroni (phase V). However, since North Macedonia was part of Yugoslavia during the 80th one publication should be considered for phase 4. The ethno-taxonomic dictionary “Fjalorth etnobotanik i shqipes” by Shefki Sejdiu (1984) is considered primarily because it describes the local names of medicinal and aromatic plants.

The second study recorded from North Macedonia was conducted by Rexhepi et al, who pioneered ethnobiological research of phase 5 in Sharr Mountain in North Macedonia in 2013, in collaboration with Andrea Pieroni & Cassandra L. Quave. Issues regarding TEK about Sharr Mountain were also published as a chapter in the book Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation (2014) by Rexhepi et al. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans is the first ethnobotany book on one of the most biologically and culturally diverse regions of the world and is a valuable resource for both scholars and students interested in the field of ethnobotany.

If we consider the coining of the term ‘Aboriginal Botany’ in 1874 as the beginning point of academic ethnobiology, then it has taken almost a century for ethnobiology to get started in North Macedonia; like in Europe and elsewhere, North Macedonian ethnobiologists initially focused on the medicinal uses of plants.

The progression of North Macedonian ethnobiology toward phase 5?

Ethnobiological research in the Republic of North Macedonia has primarily focused on specific regions, with significant studies conducted in the Polog, Southwestern, Pelagonia, and Northeastern regions. These areas have revealed diverse ethnobiological practices, encompassing traditional knowledge about plants, animals, and their ecological significance. However, other regions, including Eastern, Skopje, and Vardar, remain largely unexplored, leaving a substantial gap in understanding the full spectrum of ethnobiological heritage within the country. By extending ethnobiological investigations to these understudied areas, scholars can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of cultural practices, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable resource management across North Macedonia.

Our analysis of the nature of ethnobiology publications from North Macedonia from 1800 to 2024 shows that 3 publications could be classified as phase 4 and 12 as phase 5. Subdiscipline-wise, ethnobotany has received special attention with 9 publications, followed by ethnomedicine (1), ethnozoology (1), and ethnomycology (1). Four publications were categorized as ethnobiology as they dealt with more than one sub-discipline. Data for the past ten years (2014–2024) shows that the last decade has seen a manifold increase in the number of papers. Although in 2013–2014, research from Sharr and Korab Mountain focused on the documentation of biodiversity traditionally used by local people, the majority of such studies involved international collaboration which can be considered as phase 5.

Comparison with neighboring countries

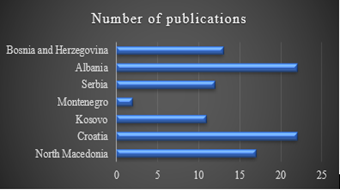

The methodological approach of this research is based on comparative analysis. Figure 2 provides data on the number of publications in neighboring countries, where Croatia produced 22 publications, Albania 22, Bosnia and Herzegovina 13, Serbia 12, Kosovo 11, and Montenegro just two.

Figure 2: Comparison of publications for all subfields of ethnobiology.

Between 2010 and 2024, aligned with phase 5, there was a growth in the overall rate of publications. However, it is encouraging to note that 9 publications from North Macedonia during the same period were of phases 3, 4, and phase 5 in nature. This trend is also observed in data from neighboring countries. The table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal research across the Balkan region, highlighting the significant number of studies conducted in countries such as Albania, Serbia, and North Macedonia. These countries show a high frequency of references, indicating active academic interest in traditional plant knowledge and its uses. Some key authors, particularly Pieroni et al., appear repeatedly, especially in Albania, underscoring their significant contributions to the field. Countries like Kosovo and Montenegro are represented by fewer studies, potentially indicating newer or less extensive research. The focus of these studies is largely on the medicinal and edible uses of plants, reflecting the cultural significance of ethnobotany. The table also reveals patterns of collaboration between local and international researchers, enhancing the exchange of knowledge across borders.

Table 2: Comparison of publications.

| Country | No of publications | References |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | -13 | Savić et al. (2019); Šarić-Kundalić et al. (2011); Ginko et al. (2023); Ferrier et al. (2015); Redzic (2010); Muratović and Parić (2023); Redžić and Ferrier (2014); Kerleta-Tuzovi and Izi (n.d.); Łuczaj and Dolina (2015); Šarić-Kundalić et al. (2010); Vitasović-Kosić et al. (2020); Redžić (2007). |

| Albania | -22 | Pieroni (2008); Pieroni and Quave (2014); Pieroni et al. (2015); Saraçi and Damo (2021); Bajrami (2023); Pieroni et al. (2014); Pieroni (2017); Pieroni and Sõukand (2017); Pieroni et al. (2014); Papajani et al. (2014); Jallo (2015); Tomasini and Theilade (2019); Pieroni et al. (2005); Imami et al. (2015); Quave and Pieroni (2014); Saraçi et al. (2023); Bernard-Mongin et al. (2021); Jani et al. (2017); Bussmann et al. (2016); Dinga et al. (2001); Demiri (1958); Avrami (1899). |

| Serbia | -12 | Dajić Stevanović et al. (2014); Gavrilović et al. (2024); Janaćković et al. (2019); Jarić et al. (2024); Jarić et al. (2014a); Jarić et al. (2014b); Marković et al. (2024); Pieroni et al. (2011); Šavikin et al. (2013); Simić et al. (2024); Veljković et al. (2021); Zlatković et al. (2014). |

| Montenegro | -2 | Menković et al. (2011); Menković et al. (2014). |

| Kosovo | -11 | Mustafa et al. (2015); Mustafa et al. (2012); Mustafa et al. (2020); Mustafa et al. (2012); Mustafa & Hajdari (2014); Mustafa et al. (2020); Mullalija et al. (2021); Hajdari et al. (2018); Pieroni et al. (2017); Icka & Damo (2023); Pieroni et al. (2017). |

| Croatia | -22 | Pieroni et al. (2003); Łuczaj et al. (2024); Łuczaj et al. (2021); Vitasović Kosić et al. (2017); Krželj & Vitasović Kosić (2020); Dolina et al. (2016); Łuczaj et al. (2019); Ninčević Runjić et al. (2024); Łuczaj et al. (2013); Dolina & Łuczaj (2014); Purgar et al. (2024); Jug-Dujaković & Łuczaj (2016); Łuczaj et al. (2013); Łuczaj et al. (2018); Solarov et al. (2022); Pieroni & Giusti (2008); Vitasović Kosić (2019); Vitasović Kosić (2022); Husnjak Malovec et al. (2024); Vitasović-Kosić et al. (2018); Turković (2003). |

| North Macedonia | -16 | Rexhepi et al. (2014); Rexhepi et al. (2013); Pieroni et al. (2013); Rexhepi (2018); Rexhepi (2021); Novik (2020); Berisha et al. (2022); Rexhepi et al. (2024); Rexhepi et al. (2018); Rexhepi & Reka (2020); Rexhepi et al. (2018); Elsie (1999); Doda & Nopcsa (2007); Miskoska-Milevska et al. (2020); Kačeva (2001); Krsteva (1996) |

It is promising to observe that researchers in these Balkan countries are increasingly prioritizing adherence to ethical standards set by their institutions, governments, or professional codes. They are also emphasizing the importance of obtaining prior informed consent—whether written, verbal, or through direct agreements with communities—and recognizing local people as key knowledge holders by implementing benefit-sharing agreements with them. Notably, during phase 5, four out of seven countries demonstrated a growing interest in biocultural diversity and socioecological systems.

Conclusion

Though North Macedonian ethnobiology only started after Phase 4, it is encouraging to note that the region has kept up with the pace of developments happening in the field. In the future, the international research community should especially work with researchers from Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina since they are considered developed countries with robust economies, which would facilitate local mobilization of resources.

References

- Avrami T. (1899). Emna drush, lulesh e barish-tash (Names of trees, flowers and herbs). Albania, 10:9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bajrami, A. (2023). Current status of ethnobotany in Albania. European Journal of Medicine and Natural Sciences, 6(1):9-17.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bala P. (1985). Indigenous medicine and the state in ancient India. Anc Sci Life, 5(1):1-4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beck, L.Y. (ed. Trans.). (2005). Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus: De Materia Medica. Olms-Weidmann, Hildesheim, Germany.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Berisha, R., Sõukand, R., Nedelcheva, A., & Pieroni, A. (2022). The importance of being diverse: the idiosyncratic ethnobotany of the Reka Albanian Diaspora in North Macedonia. Diversity, 14(11):936.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bernard-Mongin, C., Hoxha, V., & Lerin, F. (2021). From total state to anarchic market: management of medicinal and aromatic plants in Albania. Regional Environmental Change, 21(1):5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bussmann, R. W., Paniagua Zambrana, N. Y., Sikharulidze, S., Kikvidze, Z., Kikodze, D., Tchelidze, D., ... & Pieroni, A. (2016). Your poison in my pie—The use of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) leaves in Sakartvelo, Republic of Georgia, Caucasus, and Gollobordo, Eastern Albania. Economic Botany, 70:431-437.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Castetter EF. (1944). The domain of ethnobiology. Am Nat, 78(774):158-70

Publisher | Google Scholor - Clement D. (1988). The historical foundations of ethnobiology (1860-1899). J Ethnobiol, 18(2):161

Publisher | Google Scholor - Conklin H. (1954). An ethnoecological approach to shifting agriculture. Trans N Y Acad Sci, 17(2):133-142.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dajić Stevanović, Z., Petrović, M., & Aćić, S. (2014). Ethnobotanical knowledge and traditional use of plants in Serbia in relation to sustainable rural development. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: perspectives on sustainable rural development and reconciliation, 229-252.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Damo, R., Icka, P., & Ismaili, M. (2012). Biocultural diversity in Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo. SEEU Review, 8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Demiri M. (1958). Material nga mjek ̈esia popul-lore, Buletini i Universitetit Shtetëror të Tiranës, Seria Shkencat Natyrore, 2:150-151.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dinga L., Topuzi L., Onuzi A., Kongjika S. (2001). Plants in the Albanian culture. In Ricciardi L., MyrtaA., De Castro F. (ed.). Options M ́editerran ́eennes:S ́erie A. S ́eminaires M ́editerran ́eens, 47:183-196

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dioscorides, P. (70 CE). De Materia Medica.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Doda BE, Nopcsa F. (2007). Albanisches Bauern-leben in oberen Rekatal dei Dibra (Make-donien).LIT, Vienna.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dolina, K., & Luczaj, L. (2014). Wild food plants used on the Dubrovnik coast (south-eastern Croatia). Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae, 83(3).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dolina, K., Jug-Dujakovic, M., Luczaj, L., & Vitasovic-Kosic, I. (2016). A century of changes in wild food plant use in coastal Croatia: the example of Krk and Poljica. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae, 85(3).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elsie, R. (1999). The Viennese scholar who almost became King of Albania: Baron Franz Nopcsa and his contribution to Albanian studies. East European Quarterly, 33(3):327-345.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ferrier, J., Saciragic, L., Trakić, S., Chen, E. C., Gendron, R. L., Cuerrier, A., ... & Arnason, J. T. (2015). An ethnobotany of the Lukomir highlanders of Bosnia & Herzegovina. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 11:1-17.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gavrilović, M., Milutinović, M., Zlatković, B., Radulović, M., Miletić, M., Trajković, M., ... & Janaćković, P. (2024). An ethnobotanical study on the usage of wild plants from Tara Mountain (Western Serbia). Botanica Serbica, 48(2):247-262.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ginko, E., Demirović, E. A., & Šarić-Kundalić, B. (2023). Ethnobotanical study of traditionally used plants in the municipality of Zavidovići, BiH. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 302:115888.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hajdari, A., Pieroni, A., Jhaveri, M., Mustafa, B., & Quave, C. L. (2018). Ethnomedical Knowledge among Slavic Speaking People in South Kosovo. Ethnobiology & Conservation, 7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hunn E. (2007). Ethnobiology in four phases. J Ethnobiol, 27(1):1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Husnjak Malovec, K., Valjak, N., Jadan, Z., Pernar, A., Hruševar, D., Mitić, B., ... & Sandev, D. (2024). Wild plant use in Hrvatsko zagorje region (NW Croatia)-traditions and practices on the verge of disappearance. In XX International Botanical Congress Madrid Spain, 829-829.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Icka, P., & Damo, R. (2023). Traditional tea uses of wild and cultivated plantsin Albania and Kosovo, an ethnobotanical review. Science. Business. Society, 8(1):10-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Imami, D., Ibraliu, A., Fasllia, N., Gruda, N., & Skreli, E. (2015). Analysis of the medicinal and aromatic plants value chain in Albania. Gesunde Pflanzen, 67(4):155-164.

Publisher | Google Scholor - International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE): The ISE code of ethics.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jallo, C. (2015). Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Production and Use in Albania: Historic and Modern Effects on Trade Policy, Poverty & Culture. University of California, Davis.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Janaćković, P., Gavrilović, M., Savić, J., Marin, P. D., & Stevanović, Z. D. (2019). Traditional knowledge on plant use from Negotin Krajina (Eastern Serbia): An ethnobotanical study.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jani, S., Miho, L., Çakalli, A., & Dervishej, L. (2017). Landraces in Albanian Alps area: perspectives for on farm conservation and production for quality and local markets. Albanian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 139-145.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jarić, S., Kostić, O., Miletić, Z., Marković, M., Sekulić, D., Mitrović, M., & Pavlović, P. (2024). Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal research into medicinal plants in the Mt Stara Planina region (south-eastern Serbia, Western Balkans). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 20(1):7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jarić, S., Mitrović, M., & Pavlović, P. (2014). An ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal study on the use of wild medicinal plants in rural areas of Serbia. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation, 87-112.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jarić, S., Mitrović, M., Karadžić, B., Kostić, O., Djurjević, L., Pavlović, M., & Pavlović, P. (2014). Plant resources used in Serbian medieval medicine. Ethnobotany and Ethnomedicine. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 61:1359-1379.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jones, V. (1941). The nature and status of ethnobotany. Chronica Botanica 6:219-221.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jug-Dujaković, M., & Łuczaj, Ł. (2016). The contribution of Josip Bakić's research to the study of wild edible plants of the Adriatic coast: A military project with ethnobiological and anthropological implications. Slovak Ethnology/Slovenský národopis, 64(3).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kerleta-Tuzović, V., & Izi, B. Ethnobotanical study of traditionally used plants in human therapy of Treštenica and Tulovići, northeast Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Krželj, M., & Vitasović Kosić, I. (2020). Ethnobotanical use of wild growing plants: food, feed and folk medicine in Šestanovac municipality area. Krmiva: Časopis o hranidbi životinja, proizvodnji i tehnologiji krme, 62(1):3-13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., & Dolina, K. (2015). A hundred years of change in wild vegetable use in southern Herzegovina. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 166:297-304.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., Dolina, K., Fressel, N., & Perković, S. (2014). Wild food plants of Dalmatia (Croatia). Ethnobotany and biocultural diversities in the Balkans: perspectives on sustainable rural development and reconciliation, 137-148.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Luczaj, L., Fressel, N., & Perkovic, S. (2013). Wild food plants used in the villages of the Lake Vrana Nature Park (northern Dalmatia, Croatia). Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae, 82(4).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., & Vitasović-Kosić, I. (2019). Plants in alcoholic beverages on the Croatian islands, with special reference to rakija travarica. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 15:1-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., Jeričević, M., & Vitasović-Kosić, I. (2024). Ethnobotany of the ritual plants of the Adriatic islands (Croatia) associated with the Roman-Catholic ceremonial year. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae, 93:180804.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., Jeričević, M., & Vitasović-Kosić, I. (2021). Insular pharmacopoeias: Ethnobotanical characteristics of medicinal plants used on the Adriatic islands. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12:623070.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., Vitasović-Kosić, I., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., & Jeričević, M. (2018). Ethnobotany of the Adriatic islands in Croatia. In 10th Conference on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Southeast European Countries, 25-25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Łuczaj, Ł., Zovko Končić, M., Miličević, T., Dolina, K., & Pandža, M. (2013). Wild vegetable mixes sold in the markets of Dalmatia (southern Croatia). Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 9:1-12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Marković, M. S., Pljevljakušić, D. S., Matejić, J. S., Nikolić, B. M., Zlatković, B. K., Rakonjac, L. B., ... & Stankov Jovanović, V. P. (2024). Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Pirot District (southeastern Serbia). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 71(3):1201-1220.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Menković, N., Šavikin, K., Tasić, S., Zdunić, G., Stešević, D., Milosavljević, S., & Vincek, D. (2011). Ethnobotanical study on traditional uses of wild medicinal plants in Prokletije Mountains (Montenegro). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 133(1):97-107.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Menković, N., Šavikin, K., Zdunić, G., Milosavljević, S., & Živković, J. (2014). Medicinal plants in northern Montenegro: traditional knowledge, quality, and resources. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation:197-228.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Miskoska-Milevska, E., Stamatoska, A., & Jordanovska, S. (2020). Traditional uses of wild edible plants in the Republic of North Macedonia. Phytol. Balc, 26:155-162.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mullalija, B., Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2021). Ethnobotany of rural and urban Albanians and Serbs in the Anadrini region, Kosovo. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 68:1825-1848.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muratović, E., & Parić, A. (2023). Plant ethnomedicine in Bosnia and Herzegovina, past and present. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 26:1-27.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mustafa, B., & Hajdari, A. (2014). Medical ethnobotanical studies in Kosovo. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation, 113-133.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Krasniqi, F., Hoxha, E., Ademi, H., Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2012). Medical ethnobotany of the Albanian Alps in Kosovo. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 8:1-14.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Pajazita, Q., Syla, B., Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2012). An ethnobotanical survey of the Gollak region, Kosovo. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 59: 739-754.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Pieroni, A., Pulaj, B., Koro, X., & Quave, C. L. (2015). A cross-cultural comparison of folk plant uses among Albanians, Bosniaks, Gorani and Turks living in south Kosovo. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 11:1-26.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Pulaj, B., Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2020). Medical and food ethnobotany among Albanians and Serbs living in the Shtërpcë/Štrpce area, South Kosovo. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 22:100344.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mustafa, B., Mullalija, B., Pieroni, A., & Hajdari, A. (2020) An ethnobotany survey of the Rahovec municipality, Kosovo. Macedonian Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 66(2): 43-44.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ninčević Runjić, T., Jug-Dujaković, M., Runjić, M., & Łuczaj, Ł. (2024). Wild Edible Plants Used in Dalmatian Zagora (Croatia). Plants, 13(8):1079.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Novik, A. A. (2020). Medicinal herbs in folk medicine of the aromyns in malovishta (North macedonia): Ethnolinguistic studies. Балканско езикознание/Linguistique balkanique, 59(2):323-332.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Papajani, V., Ibraliu, A., Miraçi, M., & Rustemi, A. (2014). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants traditionally used in Fieri district, Albania.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A. (2008). Local plant resources in the ethnobotany of Theth, a village in the Northern Albanian Alps. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 55:1197-1214.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A. (2017). Traditional uses of wild food plants, medicinal plants, and domestic remedies in Albanian, Aromanian and Macedonian villages in South-Eastern Albania. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 9:81-90.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., & Giusti, M. E. (2008). The remedies of the folk medicine of the Croatians living in Ćićarija, northern Istria. Collegium Antropologicum, 32(2):623-627.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., & Quave, C. L. (2014). Wild food and medicinal plants used in the mountainous Albanian North, Northeast, and East: A comparison. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation, 183-194.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., & Sõukand, R. (2017). The disappearing wild food and medicinal plant knowledge in a few mountain villages of North-Eastern Albania. Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality, 90:58-67.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Cianfaglione, K., Nedelcheva, A., Hajdari, A., Mustafa, B., & Quave, C. L. (2014). Resilience at the border: traditional botanical knowledge among Macedonians and Albanians living in Gollobordo, Eastern Albania. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 10:1-31.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Dibra, B., Grishaj, G., Grishaj, I., & Maçai, S. G. (2005). Traditional phytotherapy of the Albanians of Lepushe, northern Albanian alps. Fitoterapia, 76(3-4):379-399.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Giusti, M. E., & Quave, C. L. (2011). Cross-cultural ethnobiology in the Western Balkans: medical ethnobotany and ethnozoology among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia. Human Ecology, 39:333-349.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Giusti, M. E., Münz, H., Lenzarini, C., Turković, G., & Turković, A. (2003). Ethnobotanical knowledge of the Istro-Romanians of Žejane in Croatia. Fitoterapia, 74(7-8): 710-719.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Ibraliu, A., Abbasi, A. M., & Papajani-Toska, V. (2015). An ethnobotanical study among Albanians and Aromanians living in the Rraicë and Mokra areas of Eastern Albania. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 62:477-500.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Nedelcheva, A., Hajdari, A., Mustafa, B., Scaltriti, B., Cianfaglione, K., & Quave, C. L. (2014). Local knowledge on plants and domestic remedies in the mountain villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania). Journal of Mountain Science, 11:180-193.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Rexhepi, B., Nedelcheva, A., Hajdari, A., Mustafa, B., Kolosova, V., ... & Quave, C. L. (2013). One century later: the folk botanical knowledge of the last remaining Albanians of the upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9:1-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pieroni, A., Sõukand, R., Quave, C. L., Hajdari, A., & Mustafa, B. (2017). Traditional food uses of wild plants among the Gorani of South Kosovo. Appetite, 108:83-92.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Powers, Stephen. 1874. “Aboriginal Botany”. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 5 (1873–1874):373-379.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Purgar, D. D., & Erhatić, R. Dr. Siniša Srečec, Križevci College of Agriculture, Križevci, Croatia Dr. Dario Kremer, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry, Pharmaceutical Botanical Garden “Fran Kušan”, Zagreb, Croatia Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ksenija Karlović, Universtiy of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Zagreb, Croatia.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2014). Fermented foods for food security and food sovereignty in the Balkans: a case study of the Gorani people of Northeastern Albania. Journal of Ethnobiology, 34(1):28-43.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Redžić, S. (2007). The ecological aspect of ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology of population in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Collegium antropologicum, 31(3):869-890.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Redzic, S. (2010). Wild medicinal plants and their usage in traditional human therapy (Southern Bosnia and Herzegovina, W. Balkan). J Med Plants Res, 4(11):1003-1027.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Redžić, S., & Ferrier, J. (2014). The use of wild plants for human nutrition during a war: Eastern Bosnia (Western Balkans). Ethnobotany and biocultural diversities in the balkans: perspectives on sustainable rural development and reconciliation, 149-182.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi B, Abdija Xh (2025). Ethnozoological insights into animal-derived non-timber forest products in North Macedonia. Knowledge International Journal.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B. (2018). Ethnobotanical Study of Some Medicinal and Edible Plants in Northeastern Statistical Region of Macedonia. International Journal of Advances in Science Engineering and Technology, 6(1):93-99.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B. (2021). Current status of functional food and medicinal plants in ethnobotany studies of Asteraceae family among albanians in three western balkan countries: an overview of publications in the field. International Journal of Food Technology and Nutrition, 4(7-8):16-26.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., & Reka, A. (2020). Ethno-mycological knowledge of some wild medicinal and food mushrooms from Osogovo Mountains (North Macedonia). Journal of Natural Sciences and Mathematics of UT, 5(9-10):10-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., Bajrami, A., & Mustafa, B. (2018). Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in pelagonia region (southwestern macedonia). International Journal of Advances in Science Engineering and Technology, 6(1):57-61.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., Bajrami, A., & Mustafa, B. (2018). Three ethnic groups, one territory: perspectives of an ethnobotanical study from southwestern Macedonia. Universi, 4(1):43-109.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., Luma, Q., Bajrami, A., & Haziri, A. (2024). Ethnobotany of local people in Glloboçica (Republic of Kosovo). Journal of Natural Sciences & Mathematics JNSM, 9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Rexhepi, J.R., Quave, C.L., and Pieroni, A. (2014). Cross-cultural ethnobotany of the Sharr Mountains (northwestern Macedonia). In: Pieroni, A., and Quave, C.L. (Eds.), Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans. New York, NY: Springer, 67-86.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Rushidi-Rexhepi, J., Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2014). Cross-cultural ethnobotany of the Sharr Mountains (northwestern Macedonia). Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation, 67-86.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rexhepi, B., Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Rushidi-Rexhepi, J., Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2013). Traditional medicinal plant knowledge among Albanians, Macedonians and Gorani in the Sharr Mountains (Republic of Macedonia). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 60: 2055-2080.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Robbins, W.W., J.P. Harrington, and B. Freire-Marreco. (1916). Ethnobotany of the Tewa Indians. U. S. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 55:1-118.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saraçi, A., & Damo, R. (2021). A historical overview of ethnobotanical data in Albania (1800s-1940s). Ethnobiology and Conservation, 10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saraçi, A., Bajrami, A., & Damo, R. (2023). Plants and Religion-Religious Motivations in Naming of Plants in Albania. Collegium antropologicum, 47(2):163-169.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Šarić-Kundalić, B., Dobeš, C., Klatte-Asselmeyer, V., & Saukel, J. (2011). Ethnobotanical survey of traditionally used plants in human therapy of east, north and north-east Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 133(3):1051-1076.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Šarić-Kundalić, B., Fritz, E., Dobeš, C., & Saukel, J. (2010). Traditional medicine in the pristine village of Prokoško lake on Vranica Mountain, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 78(2):275.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Savić, J., Mačukanović-Jocić, M., & Jarić, S. (2019). Medical ethnobotany on the Javor mountain (Bosnia and Herzegovina). European journal of integrative medicine, 27:52-64.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Šavikin, K., Zdunić, G., Menković, N., Živković, J., Ćujić, N., Tereščenko, M., & Bigović, D. (2013). Ethnobotanical study on traditional use of medicinal plants in South-Western Serbia, Zlatibor district. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 146(3), 803-810.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sejdiu, S. (1984). Fjalorth etnobotanik i shqipes. Rilindja

Publisher | Google Scholor - Silva, T. C. da, Medeiros, P. M., Balcazár, A. L., Araújo, T. A. de S., Pirondo, A., & Medeiros, M. F. T. (2014). Historical ethnobotany: An overview of selected studies. Ethnobiology and Conservation, 3(4):1-12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Simić, M. N., Joković, N. M., Matejić, J. S., Zlatković, B. K., Djokić, M. M., Stankov Jovanović, V. P., & Marković, M. S. (2024). Traditional uses of plants in human and ethnoveterinary medicine on Mt. Rujan (southeastern Serbia). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 71(6), 3061-3081.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Solarov, S., Eljuga, G., Ilić, M., Živković, J., Jovanović-Lješković, N., & Šavikin, K. (2022). Traditional use of medicinal plants in rural areas of Osijek-Baranja County, Republic of Croatia. Lekovite sirovine, (42):10-23.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Svanberg, Ingvar, Łukasz Łuczaj, Manuel Pardo-De-Santayana, and Andrea Pieroni. 2011. “History and Current Trends of Ethnobiological Research in Europe “. In Ethnobiology, edited by E. N. Anderson, D. Pearsall, E. Hunn, and N. Turner, 189-212. Wiley-Blackwell.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tomasini, S., & Theilade, I. (2019). Local knowledge of past and present uses of medicinal plants in Prespa National Park, Albania. Economic Botany, 73, 217-232.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Turkovi, A. (2003). Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Istro-Romanians of Zejane in Croatia. Fitoterapia, 74:710719.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Veljković, B., Karabegović, I., Acić, S., Topuzović, M., Petrović, I., Savić, S., & Dajić-Stevanović, Z. (2021). The wild raspberry in Serbia: an ethnobotanical study. Botanica Serbica, 45(1):107-117.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vitasović Kosić, I. (2019). Traditional feed for animals-the ethnobotanical aspects of using plants in the Mediterranean part of Croatia. In 26. međunarodno savjetovanje KRMIVA= 26th international conference KRMIVA, 58-59

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vitasović Kosić, I. (2022). Folk medicine in Croatia-treatments and prevention of animal health. In 27. međunarodno savjetovanje KRMIVA= 27th international conference KRMIVA ,11-11

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vitasović Kosić, I., Juračak, J., & Łuczaj, Ł. (2017). Using Ellenberg-Pignatti values to estimate habitat preferences of wild food and medicinal plants: an example from northeastern Istria (Croatia). Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 13:1-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vitasović-Kosić, I., Gugić, K., & Dorbić, B. (2020). Etnobotanička primjena biljaka i samoniklih gljiva u narodnoj medicini i ljudskoj prehrani Općine Vitez (Bosna i Hercegovina). Krmiva: Časopis o hranidbi životinja. proizvodnji i tehnologiji krme, 62(1):39-56.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vitasović-Kosić, I., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., Jeričević, M., & Łuczaj, Ł. (2018). Plants used in traditional alcoholic beverages of the Adriatic islands (Croatia). In 10th Conference on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Southeast European Countries (CMAPSEEC 2018), 57-57.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wolverton S. Ethnobiology 5: interdisciplinarity in an era of rapid environmental change. Ethnobiol Lett. 2013; 4:21-25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zlatković, B. K., Bogosavljević, S. S., Radivojević, A. R., & Pavlović, M. A. (2014). Traditional use of the native medicinal plant resource of Mt. Rtanj (Eastern Serbia): Ethnobotanical evaluation and comparison. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 151(1), 704-713

Publisher | Google Scholor - Žuškin E, Lipozenčić J, Cvetković P, Mustajbegović J, Schachter N, Mučić-Pučić B, et al. (2008). ancient medicine – a review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 16(3):149-57.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Качева А. 2001: Босилекот во обредите на преминот, Македонски фолклор, год. XIX, бр. 58-59, Скопје, 337-360.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Крстева А. (1996) Народната медицина, Етнологија на Македонците, МАНУ, Скопје, 247-255.

Publisher | Google Scholor