Case report

Clinical interventions to Achieve Maternal Mortality Ratio Goal by 2030-Work in Progress in India

- Suresh Kishanrao 1*

Family Physician and Public Health Consultant, Bengaluru 560022, India.

*Corresponding Author: Suresh Kishanrao, Family Physician and Public Health Consultant, Bengaluru 560022, India.

Citation: K. Suresh. (2024). Clinical interventions to Achieve Maternal Mortality Ratio Goal by 2030! Work in Progress in India, Clinical Interventions and Clinical Trials, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 2(2):1-9. DOI: 10.59657/2993-1096.brs.24.017

Copyright: © 2024 Suresh Kishanrao, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 12, 2024 | Accepted: February 26, 2024 | Published: March 09, 2024

Abstract

A moment of unimaginable joy is what a mother feels when a newborn is placed on her arms -a joy every mother should have the right to experience. But for many pregnant women in India this memory will never come to be, as the moment of birthing is often frightening. Globally the number of women and girls who die each year due to issues related to pregnancy and childbirth has dropped, from 451,000 in 2000 to 295,000 in 2017. In India estimated annual maternal deaths declined from 33800 in 2016 to 25,220 deaths in 2020.

The major complications that account for nearly two-thirds of all maternal deaths are severe bleeding (mostly PPH), infections (Puerperal Sepsis), Pregnancy induced hypertension (pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), complications from delivery and unsafe abortions.

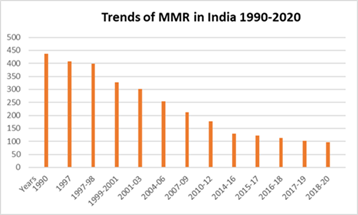

Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) of India for the period 2018-20, as per the national Sample Registration system (SRS) data was 97/100,000 live births, when compared 212 in 2007-09=212, 167 in 2011-13, 130 in 2014-16 from the same evaluated source. This translates to 8,580 additional mothers saved annually in 2020 as compared to 2016. This is also evidence of a decline of 50.4% with an ARR of 4.2 percentage over 12 years.

The improved quality of antenatal care, identifying high risk or complicated cases and their referral to emergency obstetric care facilities, increased institutional deliveries, and setting up of emergency obstetric care facilities at subdistrict hospitals have contributed to this reduction of MMR in India. Percentage of pregnant women with institutional births in public facility increased from less than 15% in NFHS-1 (1992-93) to 61.9% in NFHS-5 (2019-21). The biggest impact on MMR came through setting up of emergency obstetric care facilities at sub-district and district hospitals. The services ensured at Basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) were fundamentals of interventions, like parenteral antibiotics, parenteral anticonvulsants, uterotonic drugs, manual removal of placenta, removal of retained products of conception, assisted vaginal delivery, and resuscitation of newborn care and at Comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care (CEmONC), primarily delivered in district and medical college hospitals, included all the basic functions mentioned in BEmONC, plus capabilities for Performing Caesarean sections; Safe blood transfusion; Provision of care to sick and low-birth weight newborns, including resuscitation.

Materials and Methods: This article uses the personal involvement and experience of the author in maternal health care policy formulation and implementation support to GOI as UNICEF officer between 1989-2006 and use of evaluated data on MCH services and MMR.

Keywords: maternal mortality ratio & rate (MMR); antenatal care (ANC); emergency basic/comprehensive obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC & CEmONC); registrar general of India (RGI); sample registration scheme (SRS); national family health surveys (NFHS)

Introduction

A moment of unimaginable joy is what a mother feels when a newborn is placed on her arms -a joy every mother should have the right to experience. But for many pregnant women in India this memory will never come to be, as the moment of birthing is often frightening. Globally the number of women & girls who die each year due to issues related to pregnancy and childbirth has dropped, from 451,000 in 2000 to 295,000 in 2017 [1]. In India estimated annual maternal deaths declined from 33800 in 2016 to 25,220 deaths in 2020 [2]. In the United Nations, following the Millennium Summit, set the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for the year 2015 to i) Reduce by three-quarters of MMR, between 1990 and 2015, and ii) Achieve, universal access to reproductive health [6]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) that replaced MDGs targeted for maternal deaths, for a global MMR of less than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030. India also adopted the same goal. On 1 January 2016, the 17 (SDGs) of the 2030 were adopted by world leaders in September 2015 at an historic UN Summit and officially came into force [7]. The global MMR in 2020 was estimated at 223 down from 227 in 2015 and from 339 in 2000 [1,6,7]. The maternal mortality rate (MMR) was 2,000 per 100,000 live births (LBs) in 1947 in India’s independence year. Now, it is 97, better than the global average of 158. Since 2005, India has showed a 77 per cent decline in MMR, steeper than the 43% at the world level. In 1990 our MMR was 556/100000 LBs, as against a global MMR of 385/100000LBs. Approximately, 1.38 lakh women were dying every year on account of complications related to pregnancy and childbirth [2,3]. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality in India were suggested for prioritizing maternal and child health (MCH) nationally, for including MCH within welfare services, and for integrating vertical programs into MCH in 1990 [1].

The Office of the Registrar General, India (RGI) under the Ministry of Home Affairs, was entrusted the responsibility of estimating maternal mortality ration (MMR), in response to the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994, that recommended at least 50% reduction of MMR from the 1990 levels by the year 2000 and further one half by the year 2015. While other indicators are given annually MMR is calculated for rolling period of 3 years to get enough sample size of births in the sampled communities [4]. India as a country has made good progress and is on track to achieve 2030 target. However, there are interstate differences. An analysis of the MMR trends in last 3 decades indicates that the decline is directly related to overall development of a state or a district, availability, and accessibility of MCH services especially emergency obstetric services. Based on the recent data one notices that 11 states have an MMR more than national average and the coverage of life-saving health interventions and practices remains low due to gaps in human and other resources, skills, knowledge, in the Hindi speaking states. In a few areas there is a gap between the rich and the poor and an urban and rural divide. Access to health services is often dependent on a families’ or mother’s economic status and where they reside. To achieve the global goal of improving maternal health and to save women’s lives we need to do more to reach those who are most at risk, such as women in rural areas, urban slums, poorer households, adolescent mothers, women from minorities and tribal, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups.

Discussion

Strategies adopted for reduction of MMR

An Indian study most in Hospitals and few in the community found that 50-98% of maternal deaths were caused by direct obstetric causes like haemorrhage (APH, IPH, PPH), infections, and hypertensive disorders, ruptured uterus, hepatitis, and anaemia. Nearly 50% of maternal deaths due to sepsis were related to illegally induced abortions. In early 1990, inaccessibility, and lack of lady doctors and even nurses in remote areas and lack of coordination between levels in the delivery system and fragmentation of care accounted for the poor quality of maternal health care coupled with mass illiteracy & poor use of available services. In 1990 the advocacy started using the film called “Why did Mrs X died” a highly regarded animated video film tells the story of a global, 'universal' woman's journey through childhood, adolescence, pregnancy, a delivery, that highlights the intrapartum haemorrhage, due to low lying placenta partially separated in her uterus, that hadn't been identified in time leading to why the mother and baby died. Based on an effective advocacy by UNICEF and WHO in the early 1990’s MOH&FW, GOI developed following effective strategies:

1) GOI placed a high priority on maternal and child health (MCH) services, assured every woman the right to safe motherhood by integrating vertical programs (e.g., family planning, AIPP, IUD insertions, OCPs etc) related to MCH.

2) Promoting SBA during labour and delivery, the most critical period for complications.

3) Provided community-based clean and safe delivery system addressing 5 cleans of i) clean surface, ii) clean hands iii) clean cord cut, iv) clean cord tie, v) clean cord applications and clean place close to home, by raising maternity huts in remote villages and maternity waiting rooms in hospitals for high-risk mothers.

4) Improved the quality of antenatal care at the rural community level through health subcentres and primary health centres (proper history taking, palpation, blood pressure and foetal heart screening, risk factor screening, and referral).

5) Improved quality of care at primary & secondary health care level & referral mechanism.

6) Included MCH & family planning services in the All-India postpartum program of hospitals.

7) Examined the feasibility and established a national blood transfusion service network.

8) Improved transportation services from the community to Referral hospitals.

9) Educated young girls on health and sex; and the masses on MCH.

10) Focussed on obstetrics and gynaecology training on practical skills in management of Emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC), defined as a set of life-saving interventions, that treated the major obstetric and newborn causes of morbidity / mortality. These functions were classified as basic EmONC (BEmONC) or comprehensive EmONC (CEmONC) with provision for blood storage and transfusion facilities.

11) Gave priority to research in reproductive behaviour.

From strategies to Implementation

Development partners like UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA supported the capacities of health managers and supervisors at district and block-level to plan, implement, monitor, and supervise effective maternal health care services with a focus on high-risk pregnant women, regular routine ANC and identifying complications for referral and those in hard-to-reach, vulnerable and socially disadvantaged communities. They supported the implementation of following interventions by GOI and State Governments [4]

Reaching Every Mother

The implementation of MoH&FW, GOI policy that every delivery should be attended by a skilled health care provider in a health care facility or at homes by trained SBA in case they don’t go the hospitals.

Continuum of Care

Improving the health and nutrition of mothers-to-be and providing quality maternal and new-born health services through a continuum of care approach. This includes improving access to family planning, antenatal care during pregnancy, improved management of normal delivery by skilled attendants, access to emergency obstetric and neonatal care when needed, and timely post-natal care for both mothers and newborns.

Antenatal Care

All pregnant mothers registered for antenatal care at the nearest health facility, as soon as aware of the pregnancy, service providers assured healthy progress of their pregnancy and timely identifying of high-risk issues and refer to higher MCH care institutions if required.

Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK): JSSK launched in 2011, encompassed free maternity services for women and children, a nationwide scale-up of emergency referral systems and maternal death audits, and improvements in the governance and management of health services at all levels

The Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA)

launched by MoH&FW, GOI on 16 July 2016 envisaged to improve the quality and coverage of Antenatal Care (ANC), Diagnostics and Counselling services as part of the Reproductive Maternal Neonatal Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) Strategy. It assured a fixed day for, comprehensive and quality antenatal care free of cost to pregnant women on 9th of every month. This Programme strengthens ANC, detection and follow up of high-risk pregnancies to contribute towards reduction of MMR.

Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan (SUMAN)Yojana

SUMAN yojana is a maternity benefit initiative launched by the Ministry of Union Health and Family Welfare, GOI on October 10, 2019, during the 13th Conference of Central Council of Health and Family Welfare in New Delhi. This program provides affordable and quality healthcare solutions to pregnant women and newborns as it provides pregnant women, sick newborns, and mothers full care at zero expense up to six months after delivery, from quality hospitals and professionals.

The Objectives of the SUMAN scheme is:

a. Offer zero expenses and access to detection and management of complications during and after pregnancy.

b. Provide a zero-expense delivery & C-section facility at public health facilities.

c. Ensure zero-tolerance for denial of services to children and pregnant women.

d. Provide free transport from home to health facility & drop back after discharge.

e. Assured respectful care with privacy and support for breastfeeding.

f. Services for sick newborns & neonates and vaccination for zero cost.

Eligibility Criteria

All pregnant women and newborns are eligible to avail of the benefits under the PM SUMAN Yojana.

i)Pregnant women from all categories, including APL & BPL

ii)Newborns aged 0 to 6 months old

iii)After delivery, lactating mothers up to 6 months.

The Benefits of The Schemes

Benefits of SUMAN Yojana include.

i)zero expense delivery and C-section facilities at public health facilities,

ii)Four antenatal check-ups, components of the ANC package, one check-up during the 1st trimester, and one check-up each of three semesters under PMSMA

iii)Provides Tetanus-Diphtheria injection iron-folic acid supplementation, six home-based newborn care,

iv)Pregnant women will get free transport from home to the health facility and will get dropped back after discharge,

v)Counselling and IEC/BCC facilities for safe motherhood

vi)Pregnant women will receive hassle-free access to all medical facilities.

Progress so Far

The Public health system network consisting of 150,000 Health and Welfare Centres (H&WCs), 31,053 Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and 6,064 functional community Health Centres (CHCs) functioning across rural and urban areas in India, as of March 31, 2023. About 24,935 PHCs are in rural areas and 6,118 in urban areas. Of the CHCs 5,480 in rural and 584 in urban areas. First Referral Unit in India is a Community Health Centre, is a clinical facility equipped to provide emergency care 24*7 hours in Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Surgery, sick newborn care and Paediatrics. There are about 3500 FRUs functioning in the country as of 31 March 2023.

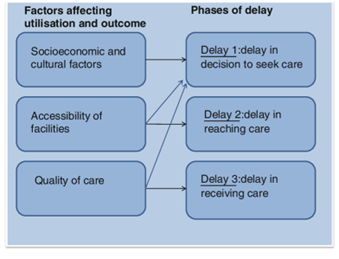

Analysing the factors affecting outcome of each pregnancy, in early 1990’s country identified 3 types of delays as shown in the figure and addressed each one of them. Dealy in seeking care for the complications of pregnancies like obstructed labour, APH, PPH were1) Socioeconomic and cultural factors and accessibility of services were addressed by a) making services available at Taluka levels by functionalizing the FRUs, involving NGOs in remote under-reached areas and urban slums and providing all services at Zero coast to the family, where it is not possible to establish public facility b) the services of Private facilities were roped in the interim through JSSK, PMSMA & SUMAN Yojana. The delay and quality at facilities is addressed through posting specialists in FRU and monitoring the quality, a task in progress.

Figure 1: Factors effecting utilization & outcome

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

In a nation as diverse and dynamic as India, addressing the challenges associated with maternal health is an ongoing journey. The commendable efforts of Government of India, Sate Governments with network of Health and Welfare centres, Primary health centres, Community Health Centres, FRUs and Medical college and District hospitals various non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA), SWADHAR, SUKARYA, and the EKUM Foundation, have played a significant role in enhancing maternal health and reducing infant mortality in the nation [13]. These and other NGO’s have extended helping hands in.

i)Tackling elevated Maternal Mortality as women, residing in rural and underserved areas, do not receive adequate prenatal care or childbirth assistance,

ii) Maternal Malnutrition Inadequate maternal malnutrition remains a pervasive issue in India, especially among marginalised communities,

iii) Limited Access to Healthcare: Access to quality healthcare varies significantly across India. Some women, in rural areas and urban slums and nomadic population, face difficulties in reaching healthcare facilities, leading to complications during pregnancy and childbirth. To address these challenges and enhance maternal health, numerous NGOs across India are actively involved in various initiatives.

Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA): SNEHA operate in urban slums, in densely populated cities where marginalised communities often lack access to healthcare, offering prenatal and postnatal care and implementing community-based interventions to enhance maternal and child health.

SWADHAR IDWC

Swadhar is another prominent NGO that operate mobile health clinics in remote and underserved regions, providing medical services, prenatal care, and health education to those who need it the most.

Sukarya

Sukarya operates in many remote villages of rural India, addressing malnutrition, poor maternal health, and limited access to healthcare facilities.

EKUM Foundation

Ekum Foundation is committed to providing maternal health support to vulnerable communities, including tribal regions, providing healthcare services, nutritional support, and awareness campaigns.

How is progress Monitored

The progress towards achievement is usually monitored looking at the process indicators like the proportion of pregnant women receiving quality ANC, proportion of Institutional or SBA attended deliveries, proportion of assisted deliveries and caesarean sections and maternal and infant deaths in each PHC, district/city or a state. NHM at different levels in India monitors these indicators using the reported coverage using HMIS data. However, the reliability of this data is questionable, on account of non-inclusion of services provided in private sector and over reporting of coverage of services and under reporting of outcomes [14,15].

Therefore, the only reliable data is generated for MMR, IMR from the RGI SRS data and for the MCH services NFHS survey data generated periodically.

How is MMR Derived?

Given the limitations of routine reporting of many vital events including MMR, Ministry of Health, and Family Welfare, GOI entrusted The Office of the Registrar General, India (RGI) under the Ministry of Home Affairs, the responsibility of estimating MMR in 1994.

The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is derived as the proportion of maternal deaths per 1,00,000 live births reported under the SRS. Besides, the 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) of the estimates based on the calculated Standard Error (SE) are also presented. Maternal Mortality Rate viz. maternal deaths to women in the ages 15-49 per lakh of women in that age group, and the lifetime risk are also presented. The lifetime risk is defined as the probability that at least one women of reproductive age (15-49) will die due to childbirth or

puerperium assuming that chance of death is uniformly distributed across the entire reproductive span and has been worked out using the following formula:

Lifetime Risk= 1-1{maternal Mortality Rate/ 100,000}35

The maternal deaths being a rare event require prohibitively large sample size to provide robust estimates, therefore, to enhance the SRS sample size, the results are derived by pooling the three years data to yield reliable estimates of maternal mortality. To take care of the undercount mainly on account of out-migration as VA forms during the period is administered after the conduct of the Half Yearly Surveys, the actual number of maternal deaths for each state has been multiplied by a ‘Correction Factor’ which is the ratio of total female deaths in a particular age group in SRS to the counts for the corresponding age group as yielded from VA forms, applied separately for different reproductive age groups. The sample registration scheme (SRS), of RGI apart from conducting Population Census & monitoring the implementation of Registration of Births and Deaths Act in the country, has been giving estimates on fertility and mortality using the Sample Registration System (SRS). It is the largest demographic sample survey in the country provides direct estimates of maternal mortality through a nationally representative sample. Verbal Autopsy instruments are administered for the deaths reported under the SRS on a regular basis to yield cause-specific mortality profile in the country. The First Report on maternal mortality in India (1997-2003) was released in October 2006 and the latest in November 2022.

Table 1: State-wise MMR as per SRS during 2018-20, The latest data shows that MMRs for Assam (215), Madhya Pradesh (197) and Uttar Pradesh (167) and were highest, followed by Chhattisgarh= 137, Odisha= 119, Bihar= 118, Rajasthan= 113, Haryana =110, Punjab= 105, West Bengal= 103 and Uttarakhand = 103, Surpassing India’s 2018–2020 estimate of 97/100,000 LBs.

| State/UTs | SRS 2018-20 | State/UTs | SRS 2018-20 |

| MMR over 150/100,000 LB | MMR Between 51-100/100000LB | ||

| Assam | 195 | Other States | 77 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 173 | Karnataka | 69 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 167 | Gujarat | 57 |

| MMR Between 101-150/100000 LB | Jharkhand | 56 | |

| Chhattisgarh | 137 | Tamil Nadu | 54 |

| Odisha | 119 | MMR Below 50/100000LB | |

| Bihar | 118 | Andhra Pradesh | 45 |

| Rajasthan | 113 | Telangana | 43 |

| Haryana | 110 | Maharashtra | 33 |

| Punjab | 105 | Kerla | 19 |

| West Bengal | 103 | ||

| Uttarakhand | 103 | ||

| All India | 97 | ||

The trends of MMR indicate that it had declined in India from 398/100 000 live births in 1997–98 to 97/100 000 in 2018-20. In a span of 2 decades. About 1.30 million maternal deaths occurred between 1997 and 2020, with about 23 800 in 2020, with most occurring in poorer states (63%) and among women aged 20–29 years (58%). After adjustment for education and other variables, the risks of maternal death were highest in rural and tribal areas of north‐eastern and northern states. The leading causes of maternal death were obstetric haemorrhage (47%; higher in poorer states), pregnancy‐related infection (12%) and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (7%) [4,5].

Figure 2: Trends of Maternal Mortality in India Source: RGI-SRS

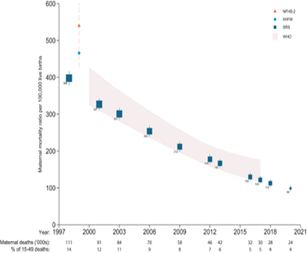

Another study analyzed trends in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 1997 through 2020, based on the 2001–2014 million Death Study to United Nations (UN). It estimated absolute maternal deaths and examined the causes of maternal death using nationally representative data sources. It partitioned female deaths (aged 15–49 years) and live birth totals, demographic totals for the country [2].

Trends in maternal mortality in India over two decades in nationally representative surveys

Figure 3: Estimated Maternal mortalities since 1997.

MCH Service Coverage data

The evaluated service coverage of all health care including maternal health care services are available through National Health and Family Survey 1-5 and the 6th is due in 2024.

Summary of NFHS 1 (1992-93): In the first NFHS While ANC ever was reported to be around 65percentage , out which 13percentage was at home by Health workers, 41percentage by doctors and 10percentage by Nurses and other health professionals in health facilities. The reason for non-availing the ANC was 59 percentage (U=66 percentage R=58 percentage ) of pregnant women or family elders did not think it was necessary and another 13 percentage did not where the services were available. Nearly 90 percentage of the urban and 75% of Rural pregnant women had not received any ANC and 3 percentage of urban and 7 percentage of Rural pregnant women had received minim of 3 ANCs recommended in that period. Only 47 percentage of ANC beneficiaries had received adequate dose of TT injections and only 45 percentage had received IFA supplementation. Institutional deliveries were less than 15 percentage in public facilities and another 11 percentage in private sector. Less than 35 percentage deliveries were attended by SBAs and remaining 65 percentage domiciliary deliveries by untrained people.

Summary of NFHS 5 (2019-21): Compared to the above bare minimum service coverage data, currently about 17 indicators of maternal care quality are collated. Starting from registration before12 weeks of pregnancy (to facilitate MTP for the unwanted pregnancy or pregnancy which poses risk to the other), increasing the number of minimum total ANC visits to 4 (for monitoring early registration and one visit in each semester with specific examination protocols and test for monitoring the quality care) and the documentation through issuing MCP cards. Postnatal visit in the first 48 hours to monitor PPH among mothers and Newborn care. Proportion of Institutional birthing and assisted deliveries particularly Caesarean sections (Public sector and private separately). Even in 2024 the proportion of domiciliary deliveries conducted by skilled birth personnel is monitored [12].

The comparison of a few common indicators over below indicates the improvement over last 2 decades, a leap and bound improvement. However, coverage of life-saving health interventions and practices remains low due to gaps in knowledge, policies, and availability of resources. This gap between the rich and the poor and an urban, urban slums, tribal and remote rural divide must be addressed.

Table 2: showing the Improvement in Comparable Indicators between 19912-93 and 2019-21

| Sl. No | Indicator | NFHS 1 (%) | NFHS 5 (%) | Change |

| 1 | Toal ANC in the pregnancy | 5 (3V) | 58 (4 visits) | 12-fold increase |

| 2 | Receiving TT | 47 | 92 | 2-fold increase |

| 3 | Receiving IFA | 44 | 70 | 1.5-fold increase |

| 4 | Deliveries By SBAs | 35 | 89.4 | 2.5-fold increase |

| 5 | Institutional Deliveries | 26 | 88.6 | 3.3-fold increase |

Table 3: Summary of NFHS 5 (2019-21)

| NFHS 5 (2019-21) | NFHS 4 (2015-16) | ||||

| Sl. No | Intervention | Urban | Rural | Total | Total |

| 40 | Mothers who had an ANC in the first trimester (%) | 75.5 | 67.9 | 70.0 | 58.6 |

| 41 | Mothers who had at least 4 ANC Visits (%) | 68.1 | 54.2 | 58.1 | 51.2 |

| 42 | Mothers whose last birth protected against NNT (%) | 92.7 | 91.7 | 92.0 | 89.0 |

| 43 | Mothers who consumed IFA for 100 days or more (%) | 54.0 | 40.2 | 44.1 | 30.3 |

| 44 | Mothers who consumed IFA for 180 days or more (%) | 34.4 | 22.7 | 26.0 | 14.4 |

| 45 | Registered pregnancies received a (MCP) card (%) | 94.9 | 96.3 | 95.9 | 89.3 |

| 46 | Mothers received PNC within 2 days of delivery (%) | 84.6 | 75.4 | 78.0 | 62.4 |

| 47 | Average OOPs expenses/delivery in Govt. facility (Rs.) | 3,385 | 2,770 | 2,916 | 3,197 |

| 48 | Home born Children taken to a check-up within 24 hours (%) | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 2.5 |

| 48 | Newborn PNC within 2 days of delivery (%) | 85.7 | 76.5 | 79.1 | NA |

| 50 | Institutional births (%) | 93.8 | 86.7 | 88.6 | 78.9 |

| 51 | Institutional births in public facility (%) | 52.6 | 65.3 | 61.9 | 52.1 |

| 52 | Home births by skilled health personnel (%) | 2.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.3 |

| 53 | Births attended by skilled health personnel (%) | 94.0 | 87.8 | 89.4 | 81.4 |

| 54 | Births delivered by caesarean section (%) | 32.3 | 17.6 | 21.5 | 17.2 |

| 55 | Births in a private by caesarean section (CS) (%) | 49.3 | 46.0 | 47.4 | 40.9 |

| 56 | Births in a public health facility by CS (%) | 22.7 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 11.9 |

The intervention that has made big impact on MMR

An analysis of interventions impacting the reduction in maternal deaths is attributed to establishment of Emergency Obstetric care across the country, though Hindi speaking big states still do not have enough of such facilities.

- Basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) comprised of the 7 fundamentals of interventions, like parenteral antibiotics, parenteral anticonvulsants, uterotonic drugs, manual removal of placenta, removal of retained products of conception, assisted vaginal delivery, and resuscitation of newborn care now available in over 6000 subdistrict levels and about 1000 cities apart from private sector.

- Comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care (CEmONC), primarily delivered in hospitals, includes all the basic functions above, plus capabilities for: Performing Caesarean sections; Safe blood transfusion; Provision of care to sick and low-birth weight newborns, including resuscitation. Such 1000 facilities are located mainly at district level [14,15].

Conclusion

The ANC is universal by now, but some remote rural and tribal areas need to be addressed. Percentage of with institutional births has reached around 89% in public facility increased. Proportion of Caesarean section have crossed the expected levels of The World Health Organization recommendations of 10 to 15% for optimal maternal and neonatal outcomes. One also sees that this excess is more due to private sector influence. Maternal death auditing continues to understand the evolving causes. While 23,800 mothers died due to chid birthing in 2020, with most of them occurring in poorer states (63%) and among women aged 20-29 years (58%). These deaths are attributed to low coverage of life-saving health interventions and practices remains due to gaps in access to services, knowledge, and availability of human resources in Hindi speaking states. In other areas there is a gap between the rich and the poor and an urban, urban slum and rural, remote rural and tribal divide. To achieve the global goal of improving maternal health and to save women’s lives we need to do more to reach those who are most at risk, such as women in rural areas, urban slums, poorer households, adolescent mothers, women from minorities and tribal, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups.

References

- (2023). What-we-do for maternal-health- A concerted action to increase access to quality maternal health services.

Publisher | Google Scholor - C Meh, et.al. (2021). Trends in maternal mortality in India over two decades in nationally representative surveys.

Publisher | Google Scholor - A Prakash et.al. (1991). Status and strategies for reduction of MMR in India, Indian Paediatrics, 28(12):1395-400.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bulletins on maternal mortality.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2022). Special bulletin on MMR in India. 2018-2020.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Millennium development goals.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sustainable Development Goals: United Nations.

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Family Health Survey, India, NFHS 1:1992-9192.

Publisher | Google Scholor - PMSMA (The Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK), National Health Mission.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2022). Overview of SUMAN (Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan Yojana).

Publisher | Google Scholor - National Family Health Survey, India, NFHS Compendium of Facts. 5:2019-2021.

Publisher | Google Scholor - The fight to improve maternal health in India and the vital role of NGOs, Team Give.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2023). National Health Profile 2022.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2024). Annual Report MOHFW, National Health Mission.

Publisher | Google Scholor