Research Article

Breast Tumors in Young Women in Cotonou: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prognosis

1Faculty of Health Sciences, Abomey-Calavi University, Cotonou-Benin.

2Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Chu Mel of Cotonou, Benin.

3University of Parakou, Parakou-Benin.

4University Clinic of Visceral Surgery, CNHU/HKM of Cotonou, Benin.

*Corresponding Author: Djima Patrice Dangbemey, Faculty of Health Sciences, Abomey-Calavi University, Cotonou-Benin.

Citation: Djima P Dangbemey, Christel M Lalèyè, R Atade, R Klikpezo, U Hounmenou, et al. (2023). Breast Tumors in Young Women in Cotonou: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prognosis. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynaecology, BRS Publishers. 2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.23.003

Copyright: © 2023 Djima Patrice Dangbemey, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: January 03, 2023 | Accepted: February 02, 2023 | Published: February 10, 2023

Abstract

Introduction: The high frequency of benign breast tumors in young women and the rarity of cancers but poor prognosis in a context of diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties deserve special attention.

Objective: To study the clinical, therapeutic and prognostic aspects of breast tumors treated in Cotonou between 2015 and 2019.

Method: This is a cross-sectional study with retrospective data collection on breast tumors treated between 2015 and 2019 in two reference hospitals in Cotonou. All patients aged under 40 treated for breast tumors were studied. The clinical, therapeutic and evolutionary characteristics of breast tumors were analyzed.

Results: Breast cancer rate was 5.2% (n=12) versus 94.8% (n=219) for benign tumors. Self-examination was the circumstance of discovery in 81% (n=187) and average medical examination time was 6.4 months. The clinical characteristics in favor of malignancy were: hard consistency in 4.7% (n=16) of cases, irregularity in 25.6% (n=88) of cases, adhesion in 11.3% (n=39) and axillary adenopathy in 10.4% (n=36) of cases. The probability of confirmation of the nature of suspicious tumor on the clinico-radiological level was 3/10. Therapeutic decisions were mostly taken on clinical and radiological arguments. Histology was not systematic. The prognosis was good for benign tumors and bad for breast cancer with a cure rate of 25%.

Conclusion: Diagnosis of breast tumors in young women is much more clinical. The absence of a radiotherapy department limits treatment and worsens the prognosis.

Keywords: cancer; breast; diagnosis; treatment; prognosis; Cotonou

Introduction

Breast pathology is varied and includes tumoral, dystrophic and inflammatory lesions. More than 50% of women are confronted during their life with a breast pathology. The vast majority of these lesions are benign, especially in young women, which is defined as any woman under the age of 40 [1]. Benign lesions can occur at any age but there is generally a peak incidence between 20 and 30 years [1]. With the development of new imaging techniques and the increasingly frequent use of micro-invasive procedures, the diagnosis of these tumors is easy and also allows the early detection of malignant tumors. Breast cancer is indeed the leading gynecological cancer in terms of frequency and the leading cause of cancer death in young women [2,3,4]. Given their high mortality, malignant tumors have been the subject of numerous studies and the guidelines for their management are fairly extensive and well established. On the other hand, despite their much higher frequency, and in the absence of their association with a risk of cancer, the management of benign tumors is not as well codified. Their management is most often based on the experience of the practitioner. Their treatment consists of therapeutic abstention, medical or surgical treatment. The latter is less recommended in young populations given the generally good evolution of these tumors and in order to avoid disturbing breast growth in these women. On the other hand, young women are more likely to have tumors with pejorative clinicopathologic characteristics and therefore more aggressive. Also, they tend to be diagnosed at later stages of the disease. This, in turn, contributes to a less favorable prognosis compared to older women. Young women benefit from the same treatment options as older patients. Surgical management includes mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery, followed by radiation therapy. The basics of chemotherapy are the same as for patients of all ages, but given their young age and fertility, younger women have special considerations [5].

It is important to take stock of the diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic aspects of breast tumors in young women treated in Cotonou in order to improve our professional practices.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of patients with breast tumors admitted to gynecological consultation in two hospitals in Cotonou (R. Benin) between 2015 and 2019. The records of patients under the age of forty (40) and who had a breast mass were retained. The only inclusion criterion was ultrasound confirmation of the breast tumor mass. Sampling was non-probability. All files that met the single inclusion criterion were retained for analysis. Data relating to socio-demographic characteristics, clinical, therapeutic and evolutionary data were analyzed. The socio-demographic characteristics studied were: age, profession/occupation, level of education, social and economic conditions. The clinical data were: family history of breast cancer, risk factors, body mass index, affected breast and quadrant, size, liquid or solid nature. The ACR classification was the radiological characteristic used. The data relating to histology were: nature (benign or malignant), histological type, receptors, lymph node involvement, vascular emboli. The data relating to the follow-up of the patients were: the duration of the follow-up, the clinical aspect of the tumor or of the operative scar, the recurrences.

The Chi 2 and Yate test allowed the comparison between the variables. Statistical significance is established for a value of p less than or equal to 5%.

Medical record information was kept secret and confidentiality was respected.

Results

Frequency of breast tumors

Of 4,562 gynecological consultations recorded, 344 were for breast tumors in women under 40 years old. That is a frequency of 7.5%. Only 231 breast tumors in young women were fully explored. On this basis, malignant tumors represented 5.2% (n=12) and benign tumors 9 4.8% (n=219).

Clinical features of breast tumors in young women

Age

The average age of the patients was 25.7 years ± 7.2 years. The youngest patients (10-24 years old) represented 47.7% (n=164) of our study population. The mean age of diagnosis of benign breast tumors was 25.7 ± 7.2 years and that of diagnosis of breast cancer was 33.5 ± 3.5 years.

Circumstances of discovery and consultation period

The circumstances of discovery of breast tumors were: self-examination of the breast in 81% (n=279) of cases, breast pain in 12.8% (n=44) and systematic clinical examination of the breast in 6, 1% (n=21). The most common reason for consultation was the discovery of a breast mass in 88% of cases (n=303). (Table 1)

The average consultation time was 6.4 months with extremes of 06 days and 05 years.

Inspection of the mammary glands

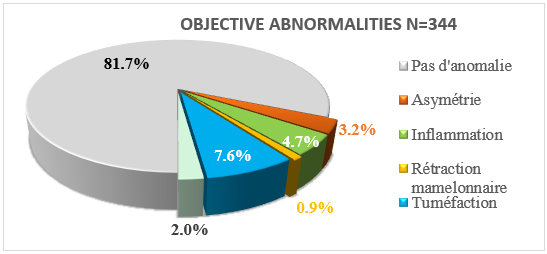

The breast was abnormal in 19.3% (n=66) of cases and breast enlargement was the most frequent anomaly in 7.6% of cases. (Figure 1).

Palpation of the mammary glands

The right breast and the upper outer quadrant were the most affected by the tumor mass in the respective proportions of 53.7% (n=187) and 31.1% (n=105).

Breast tumors of less than 2 cm were the most frequent in the proportion of 48% (n= 165). This tumor was painful in 36.4% (n=124) of cases.

The clinical characteristics in favor of the malignancy of the tumor were: the hard stony consistency in 4.7% (n=16) of the cases, the irregularity of the mass in 25.6% (n=88) of the cases, l superficial and/or deep adhesion in 11.3% (n=39) and axillary lymphadenopathy in 10.4% (n=36) of cases. (Table 1).

Radiological aspect

Tumors classified ACR4 and above represented 13.4% (n=33) of cases on ultrasound and 38.3% (n=23) of cases on mammography.

Clinical criteria for suspicion of malignancy were confirmed on imaging in 22.7% (n = 56).

Histologically

Breast tumors in young women were mostly benign tumors in 94.8% (n=219). Benign tumors were dominated by adenofibromas in 79.6% (n=184) followed by breast cysts in 12.3% (n=26).

The clinical criteria for suspicion of malignancy were confirmed by histology in 5.2% (n=12). The probability of histological confirmation of a suspicious breast tumor at the clinico -radiological level was 29.3% (12/41) or 3 confirmed cases out of 10 suspected.

Cancers are dominated by invasive carcinomas (6/12) and moderate to severe (9/12), luminal A (5/12) and rarely metastatic (2/12). (Table 3).

Diagnosis of the extension of the malignant tumor

The clinical assessment of extension was normal in almost all the patients except two cases with axillary metastasis.

The thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan (TAP) was only performed in 4 patients out of the 12 with a pulmonary metastasis. Abdominal ultrasound was used for extension assessment in 7 cases and was all negative.

| Consultation period | Workforce (n=344) | % |

| ˂ 1 | 155 | 45.0 |

| 1 – 5 | 77 | 22.4 |

| 6 – 12 | 51 | 14.8 |

| > 12 | 29 | 8.4 |

| Unspecified | 32 | 9.3 |

| Reasons for consultation | ||

| Ulceration | 02 | 0.6 |

| Flow | 04 | 1.2 |

| Inflammation | 06 | 1.7 |

| Pain | 29 | 8.4 |

| Mass | 303 | 81.1 |

| Affected breast | ||

| Right | 185 | 53.7 |

| Left | 142 | 41.3 |

| Bilateral | 17 | 5 |

| Palpation-localization of the lesion | ||

| Upper outer quadrant | 107 | 31.1 |

| Upper inner quadrant | 36 | 10.5 |

| Infero-inner quadrant | 19 | 5.5 |

| Infero-outer quadrant | 25 | 7.3 |

| Upper Quadrant Union | 46 | 13.4 |

| Union of lower quadrants | 26 | 7.6 |

| Union of outer quadrants | 39 | 11.3 |

| Union of lower quadrants | 18 | 5.2 |

| retro nipple | 28 | 8.1 |

| Size (cm) | ||

| ≤ 2 | 165 | 48 |

| 2 – 5 | 125 | 36.3 |

| ˃ 5 | 54 | 15.7 |

| Foyer | ||

| Unique | 279 | 81.1 |

| Bifocal | 37 | 10.8 |

| Multifocal | 28 | 8.1 |

| Consistency | ||

| firm/soft | 311 | 90.4 |

| Hard consistency | 16 | 4.7 |

| Unspecified | 17 | 4.9 |

| Outline | ||

| Regular | 229 | 66.6 |

| Irregular | 88 | 25.6 |

| Unspecified | 27 | 7.8 |

| Adhesion | ||

| Adherent | 39 | 11.3 |

| Mobile | 280 | 81.4 |

| Unspecified | 25 | 7.3 |

| Form | ||

| Rounded/oval | 258 | 75 |

| Polylobed | 47 | 13.7 |

| Unspecified | 39 | 11.3 |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||

| No adenopathy | 276 | 80.2 |

| Movable ipsilateral | 33 | 9.6 |

| Fixed ipsilateral | 03 | 0.8 |

| Unspecified | 32 | 9.3 |

| Sensitivity | ||

| Painful | 124 | 36.0 |

| Not painful | 220 | 64.0 |

Table 1: Clinical characteristics of breast tumors in women under 40

Figure 1: Macroscopic changes in the mammary gland

| RCA | Workforce (n) | Percentage | |

| Ultrasound | 1 | 36 | 14.6 |

| 2 | 112 | 45.5 | |

| 3 | 65 | 26.4 | |

| 4 | 24 | 9.8 | |

| 5 | 9 | 3.7 | |

| Total | 246 | 100 | |

| Mammography | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| 1 | 7 | 11.7 | |

| 2 | 15 | 25 | |

| 3 | 9 | 15 | |

| 4 | 18 | 30 | |

| 5 | 5 | 8.3 | |

| Total | 60 | 100.0 | |

| Biopsy | Indicated | 56 | 22.7 |

| Achieved | 41 | 16.7 | |

| Confirmed cancer | 12 | 5.2 |

Table 2: Radiological and histological aspects of the tumor

| Histo -prognostic features | Workforce(n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Malignant breast tumors | Histological type | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 9 | 9/12 | |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 2 | 2/12 | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 1 | 1/12 | |

| Grade | |||

| I | 3 | 3/12 | |

| II | 6 | 6/12 | |

| III | 3 | 3/12 | |

| Receivers | |||

| RE+ RP+ | 5 | 5/12 | |

| RE+ RP- | 2 | 2/12 | |

| RE-RP- | 3 | 3/12 | |

| Unspecified | 2 | 2/12 | |

| On HER2 expression | |||

| HER2+ | 5 | 5/12 | |

| HER2- | 4 | 4/12 | |

| Unspecified | 3 | 3/12 | |

| Lymph node metastases | |||

| N+ | 2 | 2/12 | |

| NOT- | 10 | 10/12 | |

| Benign breast tumors | Adenofibromas | 184 | 83.9 |

| Breast cysts | 26 | 11.9 | |

| Intramammary lymph nodes | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Low-grade phyllodes tumors | 02 | 0.9 | |

| Lipoma | 01 | 0.5 | |

| Papilloma without atypia | 01 | 0.5 |

Table 3: histological characteristics of breast tumors in young women

Treatment

Benign tumors

Therapeutic abstention was practiced in 26.9% (n=59) of the cases of benign tumours.

In 39.7% (n=87) of the cases a drug treatment was instituted. It was made of progestogen in 15% (n=33) of cases and analgesic of the first and second level in 24.6% (n=54) of cases.

Breast surgery was necessary for benign lesions in 33.3% (n=73) of cases. Lumpectomy was the most common technique in 98.6% (n=72) followed by pyramidectomy in 1.4% (Table 4).

| Directions | Number (n=73) | |

| Lumpectomy | Adenofibromas | |

| Size > 3cm | 47 | |

| Family history of cancer | 07 | |

| Patient anxiety | 12 | |

| Lipoma | 1 | |

| Phyllodes tumor | 2 | |

| Breast cysts | 3 | |

| Pyramidectomy | Papilloma | 1 |

Table 4: Indications and surgical techniques for benign breast tumors

Treatment of malignant tumors

Of the 12 cases of breast cancer, 08 indications for primary surgery and 04 neoadjuvant chemotherapy were proposed. Patey type total mastectomy with axillary dissection was performed in the 8 patients followed by adjuvant chemotherapy.

Radiotherapy was indicated in 09 patients but not performed.

Evolution

Non-operated benign tumors

A total of 127 patients were regularly followed for benign tumors, 106 of whom were not operated on. The other patients (19) were lost sight of. The average duration of follow-up of patients not operated on for benign tumors was 7 months with extremes between 3 months and 24 months.

In our series, 19.8% (n=21) of patients experienced an increase in tumor size. The average gain in height was 2.3 cm and two 02 patients had a gain of more than 4 cm.

The increase in tumor size occurred in the first 6 months of follow-up for 8 patients (38.1%) with stability thereafter. In the other patients this increase was noticed well after the first 6 months. (Table 5).

Breast tumors regressed spontaneously in part or in full in 56.2% of cases in those under 20 years old, in 22.5% of cases in those aged 20-30 years and in 28.1% of cases in those older than 20 years. 30 years (p= 0.02). Breast tumors in patients under 20 years old have a great tendency to regress. (Table 6).

| Workforce (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Total regression | 16 | 15.1 |

| Partial regression | 22 | 20.8 |

| Stability | 47 | 44.3 |

| Size increase | 21 | 19.8 |

| Total | 106 | 100 |

Table 5: Distribution according to the evolutionary trend of non-operated benign tumors

| < 20> | 20 to 30 years old | >30 years | Total | P-value | |

| Disappearance | 9 (56.2%%) | 3 (18.8%) | 4 (25%) | 16 |

0.02 |

| Regression | 11 (50%) | 6 (27.3%) | 5 (22.7%) | 22 | |

| Stability | 9 (19.1%) | 22 (46.8%) | 16 (34.1%) | 47 | |

| Increase | 5 (23.8%) | 9 (42.9%) | 7 (33.3%) | 21 | |

| Total | 34 | 40 | 32 | 106 |

Table 6: Evolution of benign breast tumors according to the age of the patient

Benign breast tumors operated on

Healing without recurrence was pronounced in 80% (n=25) of the operated patients followed (n=31). Recurrence was noted in 20% (n=6) of the operated patients followed. This recurrence was made in the same breast.

Malignant tumors

Two (02) patients were lost to sight before the initiation of treatment. After 02 years of follow-up: 02 were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with total tumor regression. Of the 08 operated patients, 02 had a local recurrence; 02 had a normal clinical and radiological examination. Three (03) patients were lost sight of and 01 death was recorded.

Discussion

Breast tumors in women under 40 accounted for 7.5% of gynecological consultation reasons in these two Cotonou hospitals. Radécka and al in Colombia in 2016 reported a frequency of 4-6% of women under 40 with breast cancer [5].

Diagnostic

Breast self-examination and finding a lump in the breast was the most common circumstance. This is the same observation by several authors such as Radécka and al in Colombia in 2016 [5].

The average time of consultation in our series was 6.4 months with extremes of 06 days and 05 years. Soum A. and al in Tunisia in 2015 noted an average duration of 7.5 months with extremes of 1 month to 24 months. [6] Financial and geographical difficulties could explain the long consultation times observed in Africa in general and in Benin in particular.

The average age of diagnosis of breast cancer in young women was 33.5 years against 25.7 years for benign tumors in our series. Soum A. and al in Tunisia in 2015 had found 23.7 years as the average age of breast cancer in their series. [6] However, it should be noted that this study focused on patients aged 19 to 25, unlike ours, which focused on patients aged 40 at most. This shows that age cannot be a positive diagnostic criterion for the nature of the breast tumour. More and more patients under the age of 40 are affected by breast cancer and breast cancer is more frequent as the age of the patient increases.[7] This state of affairs could be explained by the accumulation of aggressions suffered by the cells and by a lesser efficiency of the DNA repair mechanisms.

In our series, benign breast tumors were the most frequent in a proportion of 94.8%. This result confirms the literature data. Bonané-Thiéba and al in Ouagadoudou in the Republic of Burkina Faso in 2010 had found a prevalence of 88.9% of benign breast tumors in children under 40 [8]. Also, Njeze and al in 2014 noted in a hospital in southeastern Nigeria an 83% prevalence of benign tumors in women with an average age of 26 years [9]. In Mali, Lutuala and al had found a 95% prevalence of benign breast tumors in women under 30 [7].

Benign tumors were largely dominated by adenofibromas (70.7%) and followed by cystic tumors (19.6%). This finding is similar to that of Gueye and al in Senegal and Mensah and al in Benin who found respectively 86% and 71.4% of adenofibroma [10,11]. Foko found 72% of cases of adenofibroma, followed by lipomas in 8.7% of his patients [12]. Like other authors [14,15] we can say that adenofibroma dominates benign tumor pathology in young women. The histology also made it possible to detect 02 phyllodes tumors whose characters are superimposable with those of the adenofibromas on ultrasound. In Côte d'Ivoire Ohoui-Acko and al, exploring 51 adenofibromas diagnosed on radiology, found three (03) phyllodes tumors on histology [15]. Thus, it is not uncommon for the study of adenofibromas to lead to the discovery of a phyllodes tumour.

If benign breast tumors are frequent in the youngest, breast cancers are relatively rare in the under 40s in our series. It was 5.2% in our series. Our data corroborates those of Barbara Radecka and al in British Columbia in 2016 who found a rate varying between 4 and 6% of breast cancer in young women in their series [5]. For Njeze and Bonané-Thiéba and al the prevalence was 16.8% and 11.1% respectively [ 9; 8]. These high rates could be explained by the fact that the cases were directly recruited from anatomical pathology laboratories where the request for examination related to suspected cases of malignancy and moreover these laboratories did not receive the majority of the tumors judged benign on imaging.

The diagnosis of the nature of the breast tumor goes through several stages, the most important of which is histology. In our context the step of histology is not always the easy thing. Indeed, in addition to the economic problems or the availability of pathologists, several practitioners, in their current practice, place under surveillance the lesions described as benign on ultrasound (classified ACR 1-3). Histology is only used in the following situations: clinico-ultrasound discrepancy, family history of breast cancer or the presence of a significant risk. The same observation was made by Gueye in Senegal, which noted a low rate of anatomopathological examinations for diagnosis of benign tumors [10].

Treatment and prognosis

The management of the benign tumor can be done by expectation and/or by the application of percutaneous progestins. This attitude has made it possible to note a partial or total regression of 56% of benign tumors in the group of those under 20 years old, 22.5% in the group of 20-30 years olds and 28.1% of cases in the group of 30 years and over (p= 0.02). This is an old practice described by authors such as Neinstein LS et al in 1993 [16]. Cant and al reported a greater spontaneous resolution in the group under 20 among the 99 women followed for adenofibromas of the breast [17]. Cory and al in the United States in 2018 also noticed a spontaneous regression of breast tumors in patients under 19 years old [18]. Teenage girls with sonographically normal tumors without rapid increases in size may benefit from ultrasound follow-up as these tumors regress spontaneously in more than 10% of cases. It emerges from these studies that surgery should therefore not be the priority therapeutic option for benign breast tumors in young women classified on the basis of clinico -radiographic arguments. However, follow-up of breast tumors is very important when the therapeutic option is expectant. Indeed, Ja Yoon Jang et al in Korea, in 2017, discovered in a group of 305 women followed for tumors initially classified as benign on ultrasound, an increase in the size of the mass and a change in the status of some of these tumors as intra-canal malignant tumors posing the problem of case follow-up [19].

The literature on fibroadenomas in fact indicates that they have a self-limited development: these tumors reach an average size of 2 to 3 cm, remain static and then regress spontaneously. For this reason, many authors report that these tumors should benefit from regular follow-up or conservative treatment. In our series, 21.2% (n=73) of the mammary adenofibromas were treated by lumpectomy. This rate of lumpectomy remains low compared to that found in the series by Lutula [7] who performed lumpectomy in 66.7% of cases. Gueye and al reported a lower rate of lumpectomy for adenofibroma (16.8%) [10]. In their series, they opted for clinical -ultrasound monitoring [9]. The difference between the lumpectomy rates could be explained by the difference in the targets (age) on the one hand and the sometime diversified attitude of one practitioner to the other when faced with the breast tumor. Indeed, in the presence of benign tumors, surgery is still not the best therapeutic choice [20]. Iterative surgery is possible for tumor recurrence in the absence of correct evaluation of the indications for the first surgery. Patient anxiety was also a real reason for surgical treatment of breast masses (16.4%) in our study. For Knell and al, it was even the main reason for surgery for benign breast tumors (25.3%) among adolescent girls in the United States [21].

Tumors of the breast are rare tumors with a double fibroepithelial component and represent only 0.5% of breast tumors. These tumors are classified as grade 1 (benign), grade 2 (borderline) and grade 3 (malignant) tumors based on their histological characteristics. Their treatment is surgical and lumpectomy in an unhealthy zone (edge < 1>

In adenofibroma, the role of surgery is limited, hence surgical excision proposed in 36.1% of large-volume adenofibromas. Bendifallaha S. et al in 2015 made the same conclusions [20]. In our series, lumpectomy was indicated for family history of breast cancer, risk factors for breast cancer and for a rapidly growing tumor. Roshni Rao and al in 2018 strongly advised against conservative surgery without knowing the histological nature of the tumor [22]. The application of this recommendation remains sometimes very difficult in our context in view of the economic difficulties of the patients, the high cost of pathological anatomy examinations and even the availability of the pathological anatomy department. In this context, the use of clinical and radiological criteria for therapeutic decisions would be an important avenue even if it is insufficient. The clinical features in favor of the malignancy of the tumor in our series were the hard stony consistency in 4.7% of the cases, the irregularity of the mass in 25.6% of the cases, adhesion to the superficial plane and/or deep in 11.3% (n=39) and axillary adenopathy in 10.4% of cases. These clinical criteria for suspicion of malignancy were confirmed by imaging in 22.7% (n=56) and by histology in 5.2% (n=12). Radiologically, these were tumors classified as ACR4 and above. Faced with the risk of loss of sight for patients later found at very advanced stages of cancer, the joint use of clinico -radiological criteria for therapeutic decisions in young economically weak patients can be envisaged, taking into account the risks of diagnostic error. In our series, the probability of confirming breast cancer suspected on the basis of clinico -radiological arguments was 3 out of 10. In this case, conservative but carcinological surgery must be recommended in the context of Benin. Professionals should advocate for comprehensive universal health insurance that takes into account chronic diseases such as cancers.

The therapeutic options used in our series were mastectomy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. These therapeutic options are those observed in several series including that of Barbara Radecka and al in British Columbia in 2016 [5]. The difficulties of care in our series were related to the availability of radiotherapy which would be the cause of the absence of conservative treatment in our series.

The prognosis of breast cancer in young women was poor in our series with 25% cure versus 25% recurrence and 50

Conclusion

Breast tumors in young women are frequent and dominated by benign tumors. Their diagnosis is much more based on clinical arguments. Breast cancers in young women are not uncommon. Positive diagnosis is based on histology after triage based on clinical and radiological criteria. The treatment of breast cancer is limited by the absence of a radiotherapy service which negatively impacts the prognosis.

Highlights

- Young women breast tumors are dominated by benign tumors.

- In the context of countries with limited resources the diagnosis is based more on clinical arguments. Histology ensures positive diagnosis after clinical and radiological triage.

- The prognosis is poor and is due to the absence of a radiotherapy service

Declarations

Declaration of competing interest

None

Author contribution

Tonato Bagnan Josiane Angéline and Dangbemey Djima Patrice are the initiators of this research. They developed the protocol, monitoring data collection and analysis.

Hounmènou Ulysse were one of the principal investigators as Lalèyè Christel Marie, Atade Raoul, Klikpezo Roger

Hounkpatin Benjamin and Denakpo Justin Lewis provided data validation and proofreading.

Acknowledge

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hounmenou Ulyss for his important support in data collection and analysis.

References

- Chiquette J, Hogue JC. (2012). Senology in everyday life: breast challenges in everyday practice.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel R, Torre L, Jemal A. (2018). Global cancer statistics GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68(6):394-424.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Boyle P, Levin B. (2008). World Cancer report 2008. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer-WHO, 512.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tonato Bagnan JA, Denakpo JL, Aguida B, Hounkpatin L, Lokossou A, de Souza J and al. (2013). Epidemiology of gynecological and breast cancers at the Lagune Mother and Child Hospital (HOMEL) and at the University Clinic of Gynecology and Obstetrics (CUGO) in Cotonou, Benin. Bull Cancer, 100(2):141-146.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Barbara Radecka, Maria Litwiniuk. (2016). Breast cancer in young women. Ginekol Pol, 87(9):659-663.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Soum A, Ben A, Khadija F, Rim R, Malak A, Sihem H, Moncef M. (2015). Breast cancer in very young women aged 25 years or less in central Tunisia and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res, 21(3):553-561.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lutula S. (2008). Epidemiological, clinical and morphological study of breast tumors in Mali, Bamako [medical thesis]. Bamako: University of Bamako.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bonané-Thiéba B, Lompo-Goumbri O, Konségré V, Sawadogo J, Lamien-Sanou A, Soudré R. (2010). Epidemiological and histopathological aspects of breast diseases in Ouagadougou. J. Afr. Cancer, 2:146-150.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Njézé G. (2014). Breast Lumps: A 21‑Year Single Center Clinical and Histological Analysis. Nigerian Journal of Surgery. 20(1):38-41.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gueye S, Gueye M, Coulibaly M, Mahtouk D, Moreau JC. (2017). Benign breast tumors in the senology unit of the Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital Center in Dakar (Senegal). Pan -African Medical Journal, 27:251.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mensah E, Savi de Tove S, Koudoukpo C, Brun L, Hodonou MA, Tanou BE and al. (2015). Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of breast tumors in consultants admitted to the University Hospital of Parakou. Journal of Central African Surgery, 2(7):27-33.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Foko I. (2003). Epidemiological and anatomo-pathological study of benign breast tumors in Mali, Bamako. University of Bamako.

Publisher | Google Scholor - El-Wakeel H, Umpleby HC. (2003). Systematic review of fibroadenoma as a risk factor for breast cancer. Breast; 12:302-307.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bonané-Thiéba B, Lompo-Goumbri O, Konségré V, Sawadogo J, Lamien-Sanou A, Soudré R. (2010). Epidemiological and histopathological aspects of breast diseases in Ouagadougou. J. Afr. Cancer. 2:146-150.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ohui-acko EV, Kouadio KE, Dédé S, Gui-Bile N, Kabas R, Kouis S and al. (2017). Breast fibroadenoma: correlation between echo-mammographic and pathological data, about 55 cases. J Afr Image Med. 9(4):187-192.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Neinstein LS, Atkinson J, Diament M. (1993). Prevalence and longitudinal study of breast masses in adolescents. J Adolescent Health, 13:277-281.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cant PJ, Madden MV, Coleman MG, Dent DM. (1995). Non-operative management of breast

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cory M, Laughlin MC, Gonzalez-Hernandez J, Bennett M, Hannah G. Piper. (2018). Pediatric breast masses: an argument for observation. JSR, 228:247-252.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ja Yoon J, Sun Mi K, Jin Hwan K et al. (2017). Clinical significance of interval changes in breast lesions initially categorized as probably benign on breast ultrasound. Medicine, 96:12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bendifallaha S, Canlorbe G. (2015). Management of epidemiologically frequent benign breast tumors such as adenofibroma, phyllodes (grade 1 and 2), and papilloma: recommendations. J Gyn, 44:1017-1029.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Knell J, Jeffery L, Koning J, Grabowski E. (2015). Analysis of surgically excised breast masses in 119 pediatric patients. pediatrician Surg Int.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Roshni R, Kandace L, Lisa B and al. (2018). Select Choices in Benign Breast Disease: An Initiative of the American Society of Breast Surgeons for the American Board of Internal Medicine Choosing Wisel Campaign. Ann Surg Oncol.

Publisher | Google Scholor