Review article

Biologic Therapies for Inflammatory Arthritis: Current Use and Future Directions

1Department of Orthopaedics, ESIC Model Hospital, Noida, India.

2Department of Rheumatology, Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India.

*Corresponding Author: Rajesh Itha. Department of Orthopaedics, ESIC Model Hospital, Noida, India

Citation: Rajesh I, Sandhya B. Parabathula. (2023). Biologic Therapies for Inflammatory Arthritis: Current Use and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology and Arthritis, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 1(2):1-10. DOI: 10.59657/2993-6977.brs.23.009

Copyright: © 2023 Rajesh Itha, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: August 03, 2023 | Accepted: August 19, 2023 | Published: August 26, 2023

Abstract

Background and Aims: Inflammatory arthritis is a chronic condition that can cause joint damage, pain, and disability. Traditional treatments such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs have limitations in terms of efficacy and safety. Biologic therapies have emerged as a promising treatment option for inflammatory arthritis.

Purpose and Methods: This review article aims to provide an overview of the current use and future directions of biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis. We conducted a comprehensive literature search using various databases, including PubMed and Embase, to identify relevant studies published in English. We included randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews in our analysis.

Conclusion: Biologic therapies have revolutionized the management of inflammatory arthritis, providing patients with a more targeted and effective treatment option. While biologic therapies have demonstrated significant efficacy in clinical trials, their use is not without challenges, including cost and safety concerns. Emerging biologic therapies hold promise in addressing some of these limitations. As the field of biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis continues to evolve, further research is needed to optimize their use and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: inflammatory arthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; psoriatic arthritis; ankylosing spondylitis; biologic therapies; tumor necrosis factor inhibitors; interleukin inhibitors

Introduction

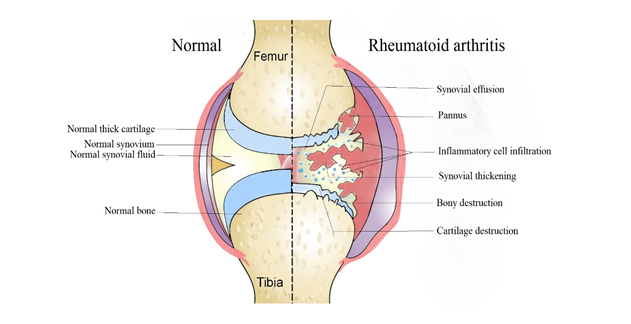

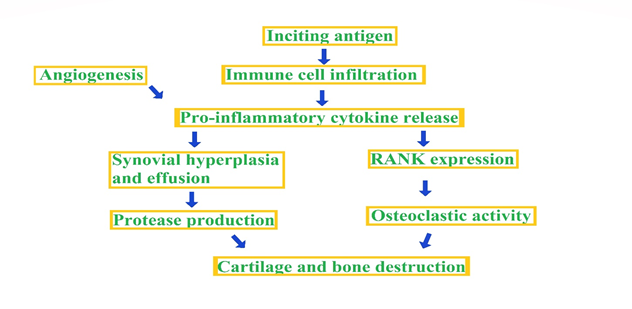

Inflammatory arthritis refers to a group of chronic autoimmune disorders that primarily affect the joints, causing inflammation and tissue damage. It is estimated that around 1% of the global population suffers from some form of inflammatory arthritis, making it a significant public health concern [1]. There are several types of inflammatory arthritis, including Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA), Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS), and Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA). While each of these conditions has unique clinical features, they share common mechanisms of disease development, including aberrant immune activation and inflammatory pathways [2] Fig 1. Inflammatory arthritis can significantly impact an individual's quality of life, leading to pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. Moreover, if left untreated or inadequately treated, it can result in joint deformity, disability, and even mortality [3].

Figure 1: Normal joint versus a Rheumatoid joint.

Figure 2: The common path way producing inflammatory arthritis.

While there is no cure for inflammatory arthritis, advances in medical research have led to the development of effective treatment options that can help manage symptoms, prevent joint damage, and improve patient outcomes. The two main approaches to treatment are traditional non-biologic therapies and biologic therapies. Traditional non-biologic therapies, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), disease modifying anti rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and glucocorticoids, have been the mainstay of treatment for inflammatory arthritis for many years. However, they have limitations in terms of efficacy, safety, and long-term use [4]. Biologic therapies, on the other hand, are a relatively new class of drugs that target specific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process. They have revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, providing new hope for patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate traditional therapies. This review article aims to provide an overview of the current use and future directions of biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis.

Traditional Treatment Options for Inflammatory Arthritis

Traditional treatment options for inflammatory arthritis are designed to manage symptoms, slow disease progression, and improve overall quality of life. These include nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), disease modifying anti rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and glucocorticoids.

NSAIDS

NSAIDs are widely used to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and improve joint function in inflammatory arthritis. They work by blocking the production of prostaglandins, which are hormone-like substances that play a role in inflammation [5]. However, NSAIDs have limitations in terms of efficacy and safety, and their long-term use can lead to adverse effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding, renal dysfunction, and cardiovascular events [6].

DMARDs

DMARDs are another class of traditional therapies used in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. They work by suppressing the immune system and reducing inflammation in the joints. DMARDs are classified as conventional or biologic, depending on their mechanism of action [7]. Conventional DMARDs, such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine, are often used as first-line therapy for inflammatory arthritis, and they can be effective in slowing disease progression and preventing joint damage [4]. Biologic DMARDs, on the other hand, are targeted therapies that work by blocking specific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process [3].

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, are potent anti-inflammatory drugs that can be used in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. They work by suppressing the immune system and reducing inflammation. Glucocorticoids can be effective in managing acute flares of disease, but their long-term use is associated with a range of adverse effects, including osteoporosis, weight gain, and increased risk of infection [8].

While traditional therapies have been the mainstay of treatment for inflammatory arthritis for many years, they have limitations in terms of efficacy, safety, and long-term use. Biologic therapies, which are a relatively new class of drugs, providing new hope for patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate traditional therapies.

Biologic therapies: Overview

The emergence of biologic therapies has revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, providing a more targeted and effective approach to disease management. Biologic therapies are designed to target specific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process, there by reducing inflammation and preventing joint damage.

TNF-α inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors are the first class of biologic therapies to be approved for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a key role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritis's. TNF-α inhibitors, such as infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab, work by blocking the activity of TNF-α, thereby reducing inflammation and preventing joint damage [9]. Clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of TNF-α inhibitors in reducing disease activity and improving joint function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritis's [10].

IL-6 inhibitors

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitors are another class of biologic therapies used in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a key role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritis's. IL-6 inhibitors, such as tocilizumab and sarilumab, work by blocking the activity of IL-6, there by reducing inflammation and preventing joint damage [11]. Clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of IL-6 inhibitors in reducing disease activity and improving joint function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritides [12].

Other biologic therapies

Other biologic therapies that have been approved for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis include abatacept, rituximab and ustekinumab. Abatacept works by inhibiting T-cell activation, thereby reducing inflammation and preventing joint damage. Rituximab works by depleting B cells, which play a role in the inflammatory process. Ustekinumab works by blocking the activity of IL-12 and IL-23, two cytokines that play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis and other inflammatory arthritides [13].

Despite the efficacy of biologic therapies in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, they are associated with a range of potential side effects, such as an increased risk of infection, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease. Long-term risks of biologic therapies are not fully understood and require ongoing monitoring and research. Therefore, careful patient selection and monitoring are essential to ensure the safe and effective use of biologic therapies in the management of inflammatory arthritis.

Table 1: Examples of biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis

| Class of biologic therapy | Example |

| TNF inhibitors | Infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab |

| Interleukin inhibitors | Anakinra, tocilizumab, sarilumab, ustekinumab |

| B cell depletion therapy | Rituximab, belimumab |

| T cell inhibitors | Abatacept |

| Janus kinase inhibitors | Tofacitinib, baricitinib |

| IL-6 receptor inhibitors | Tocilizumab, sarilumab |

Mechanisms of Action of Biologic Therapies in the Treatment of Inflammatory Arthritis

Unlike traditional treatments that act broadly to suppress the immune system, biologic therapies are designed to be more targeted, with the goal of reducing inflammation without causing wide spread immunosuppression. Several different classes of biologic therapies are currently used in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, interleukin (IL) inhibitors, and T-cell modulators.

TNF inhibitors

One of the most commonly used biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritisis TNF inhibitors, which work by binding to and neutralizing TNF, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a key role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis [14]. By blocking the action of TNF, these drugs can reduce inflammation and slow joint damage. Examples of TNF inhibitors include infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab.

IL inhibitors

IL inhibitors are another class of biologic therapies that have been shown to be effective in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. These drugs work by blocking the action of specific IL cytokines that are involved in the inflammatory response. For example, IL-6 inhibitors (tocilizumab, sarilumab) have been shown to be effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, reducing joint inflammation and damage [15].

T-cell modulators

T-cell modulators are another class of biologic therapies that target the immune system. These drugs work by modulating the activity of T cells, a type of immune cell that plays a key role in the inflammatory response. Examples of T-cell modulators include abatacept, which blocks the activation of T cells, and ustekinumab, which targets IL-12 and IL-23, two cytokines that are involved in the activation of T cells [16]. In addition to their targeted mechanisms of action, biologic therapies also have the advantage of being generally well-tolerated, with relatively few serious side effects.

The current use of biologic therapies in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis

The use of biologic therapies has significantly changed the treatment landscape for inflammatory arthritis, with many patients achieving disease remission or low disease activity.

TNF inhibitors

In particular, anti-TNF agents have been shown to be highly effective in reducing signs and symptoms of inflammatory arthritis, improving function and quality of life, and preventing joint damage progression. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of anti- TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) showed that these agents are associated with a significant reduction in disease activity, a decrease in joint erosion, and an improvement in physical function [17].

Other biologics

Other biologic agents, such as IL-6 inhibitors and B cell inhibitors, have also demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. For example, tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, has been shown to improve disease activity and reduce joint damage progression in RA patients [18]. Rituximab, a B cell inhibitor, has been approved for the treatment of RA and other autoimmune diseases and has been shown to be effective in reducing disease activity and preventing joint damage progression [19].

Efficacy and Safety of Biologic Therapies in the Treatment of Inflammatory Arthritis

The use of biologic therapies is not without potential risks; therefore, it is essential to understand the efficacy and safety profile of biologic therapies in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis.

Efficacy of Biologic Therapies

Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies have demonstrated the efficacy of biologic therapies in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. For example, a meta-analysis of RCTs found that biologic therapies were significantly more effective than placebo in improving disease activity, physical function, and radiographic progression in patients with RA [17]. Similar results have been observed in patients with PsA and AS [20, 21].

Furthermore, the use of biologic therapies in combination with traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has been shown to be more effective than DMARDs alone. A study comparing the efficacy of adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone in patients with RA found that the combination therapy resulted in significantly better outcomes in terms of disease activity, physical function, and radiographic progression [22].

Safety of Biologic Therapies

Although biologic therapies have been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, they are not without potential risks. The most common adverse events associated with biologic therapies include injection site reactions, upper respiratory infections, and gastrointestinal symptoms. More serious adverse events, such as infections, malignancy, and infusion reactions, are less common but require careful monitoring. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews have examined the safety of biologic therapies in patients with inflammatory arthritis. A systematic review of 19 RCTs and 19 observational studies found that the risk of serious infections was slightly higher in patients receiving biologic therapies compared to those receiving placebo or DMARDs [23]. However, the overall risk was low, and the benefits of biologic therapy in terms of disease control and physical function outweighed the risks.

Similarly, a meta-analysis of RCTs found that the risk of malignancy was not significantly increased in patients receiving biologic therapies compared to placebo or DMARDs [24]. However, the risk of lymphoma may be slightly increased in patients with RA, particularly in those receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy [25]. Nonetheless, the overall risk of malignancy remains low, and careful monitoring is recommended.

Table 2: Efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis

| Biologic therapy | Efficacy | Safety |

| Infliximab | High | Moderate to high |

| Etanercept | Moderate | Moderate |

| Adalimumab | High | Moderate to high |

| Certolizumab | High | Moderate to high |

| Golimumab | High | Moderate to high |

| Anakinra | Low to moderate | Low to moderate |

| Tocilizumab | High | Moderate to high |

| Rituximab | Moderate | Moderate |

| Abatacept | Moderate | Moderate |

| Tofacitinib | Moderate to high | Moderate to high |

| Baricitinib | Moderate to high | Moderate to high |

(Efficacy and safety ratings are based on clinical trial data and may vary depending on the specific patient population and disease severity.)

Challenges in the use of biologic therapies

Even though the biologic therapies have revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory arthritis by providing patients with effective options for managing their symptoms and improving their quality of life. However, these therapies are not without challenges, and clinicians must be aware of these issues when using biologic therapies to treat their patients.

Adverse events

One of the primary challenges associated with biologic therapies is the potential for adverse events. Although biologic therapies are generally safe and well-tolerated, they can be associated with a range of side effects, including infections, infusion reactions, and immune- related adverse events such as demyelination, lupus-like syndromes, and malignancies [26]. Clinicians must be vigilant in monitoring patients for these adverse events and managing them appropriately when they occur. This requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving not only rheumatologists but also infectious disease specialists, dermatologists, and other healthcare professionals as needed [4].

Resistance

Another challenge associated with biologic therapies is the development of treatment resistance or loss of response over time. This can occur due to a variety of factors, including immunogenicity (i.e., the development of antibodies against the biologic agent),drug clearance, and disease progression.[10] In some cases, switching to a different biologic therapy or combining therapies may be necessary to maintain disease control.

Cost

Cost is another important consideration when using biologic therapies. These agents can be expensive, and their high cost can limit patient access and create a burden on healthcare systems. Efforts are being made to address this issue, including the development of biosimilars (which are less expensive versions of biologic therapies) and the use of value- based pricing strategies [27].

Other

Finally, there are practical challenges associated with the use of biologic therapies, including the need for frequent monitoring, the need for specialized training to administer some agents (such as intravenous infusions), and the need for storage and handling of these agents in a specialized manner [28].

Despite these challenges, biologic therapies remain a valuable option for treating inflammatory arthritis. By understanding the potential challenges associated with these therapies and taking steps to mitigate them, clinicians can help ensure that patients receive the best possible care.

Table 3: Challenges in the use of biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis

| Challenge | Description |

| Cost | Biologic therapies are often expensive and may not be covered by insurance or accessible to all patients |

| Administration | Biologic therapies require parenteral administration, which may be inconvenient or uncomfortable for some patients |

| Monitoring | Regular monitoring is necessary to assess the efficacy and safety of biologic therapies and to detect and manage any adverse events |

| Resistance | Some patients may develop resistance to biologic therapies over time, leading to loss of efficacy |

| Infection risk | Biologic therapies increase the risk of infection, including serious and opportunistic infections |

Emerging biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis

Despite the success of currently available biologic therapies, there remains a need for additional treatment options to address the limitations of these agents. One such limitation is the lack of response in a significant proportion of patients, as well as the development of resistance to biologics over time. Furthermore, there is a concern for potential adverse effects associated with long-term biologic therapy. As such, research into emerging biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis has focused on identifying new targets and pathways for treatment [29].

JAK inhibitors

One area of interest is the Janus kinase (JAK) pathway, which is involved in the regulation of immune cell activation and inflammation. Several JAK inhibitors have been developed and are currently undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. One such inhibitor is tofacitinib, which has been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States and Europe. Tofacitinib works by inhibiting JAK1 and JAK3, resulting in the suppression of the immune response and reduction of inflammation [30].

IL-6 inhibitors

Another emerging biologic therapy is the IL-6 receptor inhibitor sarilumab, which has been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Sarilumab binds to the IL-6 receptor and blocks it signaling pathway, which is involved in the regulation of inflammatory responses. In addition to sarilumab, other IL-6 inhibitors such as tocilizumab and clazakizumab are currently being evaluated for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis [31].

Other

Other novel biologic therapies being developed for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis include agents targeting the chemokine receptor CXCR4, which is involved in the migration of immune cells to inflamed tissues. A phase II clinical trial of a CXCR4 inhibitor, AMD3100, has demonstrated promising results in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [32].

Table 4: Emerging biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis.

| Biologic therapy | Mechanism of action | Current status |

| Upadacitinib | Janus kinase inhibitor | FDA-approved for rheumatoid arthritis |

| Filgotinib | Janus kinase inhibitor | FDA-approved for rheumatoid arthritis |

| Guselkumab | Interleukin-23 inhibitor | FDA-approved for psoriatic arthritis |

| Risankizumab | Interleukin-23 inhibitor | FDA-approved for psoriatic arthritis |

| Sirukumab | Interleukin-6 inhibitor | In clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis |

| Vobarilizumab | Interleukin-6 inhibitor | In clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis |

| Atacicept | B cell inhibitor | In clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis |

| Tregalizumab | T cell inhibitor | In clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis |

The future directions and potential advancements in biologic therapy for inflammatory arthritis

Although there are still many challenges that need to be addressed to improve patient outcomes, fortunately, there are several exciting developments in biologic therapy that may offer new opportunities for improving the management of inflammatory arthritis.

JAK inhibitors

One potential area of advancement is the development of more targeted therapies that focus on specific pathways or molecular targets involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis. For example, emerging biologic therapies such as JAK inhibitors, which target the JAK/STAT pathway, have shown promising results in clinical trials and may offer a more precise and effective treatment option for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other inflammatory arthritis subtypes [33].

Pharmacogenomics

Another potential area of advancement is the use of personalized medicine approaches, such as pharmacogenomics and biomarker-guided therapy. Pharmacogenomic testing can identify genetic variations that affect an individual's response to certain drugs, allowing for more personalized treatment selection and dosing.

Biomarker-guided therapy

Similarly, biomarkers can help to identify patients who are more likely to respond to certain therapies, enabling more targeted and effective treatment strategies [4].

Drug delivery systems

Advances in drug delivery systems may also play an important role in improving the efficacy and safety of biologic therapies. For example, the use of subcutaneous injections or oral formulations may reduce the need for frequent hospital visits and decrease the risk of adverse events associated with intravenous infusion.

Novel drug formulations

Additionally, the development of novel drug formulations, such as long-acting monoclonal antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates, may improve drug bioavailability and prolong the therapeutic effect, potentially reducing the frequency of dosing [34].

Other

Advances in technology may enable the development of more sophisticated and effective therapeutic approaches for inflammatory arthritis. For example, gene therapy, stem cell therapy, and nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems are all areas of active research that may offer new treatment options for inflammatory arthritis [35]. While these approaches are still in the early stages of development, they offer exciting possibilities for improving the management of inflammatory arthritis and may eventually lead to a cure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, biologic therapies have revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, providing patients with targeted, effective, and often safer treatment options compared to traditional therapies. Biologic therapies work by targeting specific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process, thereby reducing inflammation and alleviating symptoms. While biologic therapies have demonstrated significant efficacy in clinical trials, challenges in their use still exist, such as high cost, potential adverse effects, and the need for frequent administration. Despite these challenges, emerging biologic therapies, such as biosimilars and small molecules, offer new treatment options and potential advancements in the field. Overall, biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis have provided a paradigm shift in the treatment of this debilitating disease, improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Summary of Key Findings

- Biologictherapies are a newer class of drugs that work by targetingspecific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process.

- Biologictherapies have demonstrated significant efficacy in clinical trials,with many patients achieving clinical remission or low diseaseactivity.

- The use of biologic therapies in the treatmentof inflammatory arthritishas improved patientoutcomes, including pain relief, joint function, and quality of life.

- While biologic therapies are effective, challenges in their use still exist,including high cost,potential adverse effects, and the need for frequent administration.

- Emergingbiologic therapies, such as biosimilars and small molecules, offer new treatment options and potential advancements in the field.

- Further research is needed to fully understand the long-term efficacy and safety of biologic therapies, as well as to develop more cost-effective treatment options.

Abbreviations

- AS - Ankylosing Spondylitis

- DMARDs - Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

- IL-6 - Interleukin-6

- IL inhibitors - Interleukin inhibitors

- JAK inhibitors - Janus Kinase inhibitors

- JIA - JuvenileIdiopathic Arthritis

- NSAIDs- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- PsA - PsoriaticArthritis

- RA - Rheumatoid Arthritis

- RCTs - Randomized Controlled Trials

- TNF-α - Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha

- TNF inhibitors - Tumor Necrosis Factor inhibitors

References

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. (2016). Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet, 388(10055):2023-2038.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Firestein GS. (2003). Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature, 423(6937):356-61.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McInnes IB, Schett G. (2011). The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med, (23):2205-2219.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, McAlindon T. et.al. (2016). American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol, 68(1):1-26.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Koppert W, Schmelz M. (2007). The impact of opioid-induced hyperalgesia for postoperative pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol, 21(1):65-83.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, Egger M, Jüni P. (2011). Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. (2008). Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet, 372(9636):375-82.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Buttgereit F, da Silva JA, Boers M, Burmester GR, Cutolo M, Jacobs J, Kirwan J, Köhler L, Van Riel P, Vischer T, Bijlsma JW. (2002). Standardised nomenclature for glucocorticoid dosages and glucocorticoid treatment regimens: current questions and tentative answers in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis, (8):718-722.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Feldmann M, Maini SR. (2008). Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: an education in pathophysiology and therapeutics. Immunol Rev, 223:7-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, et.al. (2016). Recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis, 76(6):960-977.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. (2014). IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Azuma J. (2009). Long-term safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, in monotherapy, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (the STREAM study): evidence of safety and efficacy in a 5-year extension study. Ann Rheum Dis, 68(10):1580-1584.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dougados M, Wei JC, Landewé R, Sieper J, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, et.al. (2020). COAST-V and COAST-W Study Groups. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-V and COAST-W). Ann Rheum Dis, 79(2):176-185.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kay J, Calabrese L. (2017). The role of TNF in rheumatoid arthritis. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, editors. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 594-602.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Isaacs JD, Salih A, Sheeran T, Patel YI, Douglas K, McKay ND, Naisbett-Groet B, Choy E. (2019). Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis over1 year: a UK real-world, open-label study. Rheumatol Adv Pract.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Raychaudhuri SP, Raychaudhuri SK, Genovese MC. (2011). IL-17 receptor and its functional significance in psoriatic arthritis. Mol Cell Biochem, 359(1-2):419-429.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, Suarez-Almazor ME, Buchbinder R, Lopez- Olivo MA, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Tugwell P. (2009). Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, Ramos-Remus C, Rovensky J, Alecock E, Woodworth T, Alten R; (2008). OPTION Investigators. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet, 371(9617):987-997.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, Stevens RM, (2004). Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med, 350(25):2572-2581.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mease PJ, Armstrong AW. (2014). Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs, 74(4):423-441.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Braun J, Sieper J. (2007). Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet, 369(9570):1379- 1390.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, Sharp J, Perez JL, Spencer-Green GT. (2006). The PREMIER study: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum, 54(1):26-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh JA, Cameron C, Noorbaloochi S, Cullis T, Tucker M, Christensen R, Ghogomu ET, Coyle D, Clifford T, Tugwell P, Wells GA. (2015). Risk of serious infection in biological treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 258-265.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Leblanc GG, Boire G, Beauchamp-Chalifour P, et al. (2014). Frequency of malignancies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics: results from the Quebec rheumatoid arthritis registry. J Rheumatol, 41(8):1602-1606.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J, Ekbom A, Backlin C, Granath F, Catrina AI, Rosenquist R, Feltelius N, Sundström C, Klareskog L. (2006). Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum, 54(3):692-701.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Furst DE. (2010). The risk of infections with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 39(5):327-46.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Brkic A, (2022). Diamantopoulos AP, Haavardsholm EA, Fevang BTS, Brekke LK, Loli L, Zettel C, Rødevand E, Bakland G, Mielnik P, Haugeberg G. Exploring drug cost and disease outcome in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs in Norway in 2010-2019 - a country with a national tender system for prescription of costly drugs. BMC Health Serv Res.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zaripova LN, Midgley A, Christmas SE, Beresford MW, Baildam EM, Oldershaw RA. (2021). Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: from aetiopathogenesis to therapeutic approaches. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J, 19(1):135

Publisher | Google Scholor - Combe B, (2013). van Vollenhoven RNovel targeted therapies: the future of rheumatoid arthritis? Mavrilumab and tabalumab as examplesAnnals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 72:1433-1435

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, Wilkinson B, Bradley JD, Gruben D, Koncz T, Krishnaswami S, Wallenstein GV, Zang C, Zwillich SH, van Vollenhoven RF; ORAL Start Investigators. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med, 370(25):2377-2386.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Burmester GR, Rubbert-Roth A, Cantagrel A, Hall S, Leszczynski P, Feldman D, Rangaraj MJ, Roane G, Ludivico C, Lu P, Rowell L, Bao M, Mysler EF. (2013). A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study of the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab versus intravenous tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (SUMMACTA study). Ann Rheum Dis, 73(1):69-74

Publisher | Google Scholor - Caspar B, Cocchiara P, Melet A, Van Emelen K, Van der Aa A, Milligan G, Herbeuval JP. (2022). CXCR4 as a novel target in immunology: moving away from typical antagonists. Future Drug Discov.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Winthrop KL. (2017). The emerging safety profile of JAK inhibitors in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 13(4):234-243

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choi, Sung-Jae. (2021). Biologic therapies for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of the Korean Medical Association, 64:95-104.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Murphy JM, Fink DJ, Hunziker EB, Barry FP. (2003). Stem cell therapy in a caprine model of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Dec;48(12):3464-3474.

Publisher | Google Scholor