Research Article

Autoimmune Systemic Diseases in Children: Epidemiology and Clinical Phenotypes in Senegal

- Diatta Boubacar Ahy *

- Malky Maysae

- Mendy Patrice

- Pie Nibirantije

- Ndiaye Tening Mame

- Fall Ndiague

- Sarr Mamadou

- Niar Ndour

- Diop Khadim

- Diadie Saer

- Diop Assane

- Ndiaye Maodo

- Diallo Moussa

- Ly Fatimata

- Niang Suzanne Oumou

Department of Dermatology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar.

*Corresponding Author: Diatta Boubacar Ahy, Department of Dermatology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar.

Citation: Diatta B Ahy, Teba A, Mendy P, Fall N, Nibirantije P, et al. (2023). Autoimmune Systemic Diseases in Children: Epidemiology and Clinical Phenotypes in Senegal. Dermatology Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia publishers. 2(1):1-7. DOI: 10.59657/2993-1118.brs.23.009

Copyright: © 2023 Diatta Boubacar Ahy, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: July 28, 2023 | Accepted: August 12, 2023 | Published: August 17, 2023

Abstract

Introduction: Systemic diseases (SD) include all non-organ-specific autoimmune and/or inflammatory disorders. In children, their severity is related to severe visceral damage and iatrogenic complications of treatment. This study aimed to determine the epidemiological, clinical evolutionary aspects of systemic diseases in children.

Methodology: A cross-sectional, analytic study was carried out in the Dermato-pediatrics Department of the Albert Royer Hospital in Dakar from January 2020 to June 2022 (30 months). We included all children aged 0 to 16 years followed up for systemic autoimmune disease.

Results: We collected 18 cases of systemic diseases in children, representing a hospital frequency of 0.36%. The SD were of the lupus type in 7 cases, dermatomyositis in 4 cases, scleroderma in 3 cases, mixed connectivity’s in 3 cases and APLS in 1 case. The sex ratio was 0.12. The mean age of the children was 10 years [4-14 years]. In lupus, lesions were acute in 5 cases, subacute in 1 case and chronic in 1 case. In dermatomyositis, the cutaneous manifestations were: periorbital erythredema, ulcer-necrotic lesions, atrophic lesions of photo-exposed areas, non-erosive cheilitis, a non-scarring alopecia, Gottron papules, poikiloderma and calcinosis. Dermatomyositis was associated with extracutaneous muscular, articular, cardiovascular and pulmonary involvement. In scleroderma, cutaneous manifestations included sclerodactyly, Raynaud's phenomenon and cutaneous sclerosis. Visceral involvement included rhythm disturbances and pulmonary fibrosis. Necrotic ulcers and cyanosis of the extremities were the circumstances in which APLS was discovered. The association lupus-dermatomyositis represented (66.7%) and lupus-APLS (33.3%). Corticosteroid therapy was administered in 38.8% of cases. The outcome was favorable in 27.77% (n=5), with death noted in 3 cases.

Conclusion: Systemic autoimmune diseases of children are rare disorders. They are characterized by their clinical polymorphism and the severity of visceral damage. Early treatment and therapeutic education of parents can improve prognosis.

Keywords: autoimmune systemic diseases; child; senegal

Introduction

Systemic diseases encompass all non-organ-specific autoimmune and/or inflammatory conditions [1]. These diseases are heterogeneous, inflammatory, and multifactorial, involving genetic, endocrine, and environmental factors [2,3]. They are common in adults, with an estimated prevalence of 5-10% of the world's population [4]. Their incidence is rare in children, with an average age of onset varying from 12 years for lupus [4], to 7 years for dermatomyositis [5], 10 years for scleroderma [6], 11 years for anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APLS) [7] and 11 years for mixed connectivity [4]. Classically, they predominate in girls [6]. These systemic diseases are serious in children, on one hand, because of their severe visceral damage, which can be life-threatening. They are also serious because of the functional impact of disabling joint pain, school absenteeism, and iatrogenic complications of treatment with corticosteroids drugs, Immunosuppressive drugs, and biotherapies [8]. The cutaneous manifestations of these systemic diseases are often inaugural, enabling early diagnosis and prognosis. However, few studies have been reported in Africa on the epidemiological profile of these systemic diseases in dermatology care centers. We, therefore, carried out this study intending to describe the epidemiological profile of systemic diseases in children, describing their different clinical presentations, identifying associated biological and immunological abnormalities, and specifying their evolutionary aspects.

Patients and methods

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study conducted over 30 months from January 2020 to June 2022 in the pediatric dermatology department of the Albert Royer National Children's Hospital in Dakar (Senegal). We included all records of children under 16 years of age hospitalized or followed up as outpatients for systemic autoimmune disease. The diagnosis of systemic disease was retained on clinical, biological, and immunological grounds. For systemic lupus, we used the ACR and SLICC criteria [9], those of Bohan and Peter for dermatomyositis [10], and ACR/EULAR for scleroderma [11]. A survey form was used to collect socio-demographic information, personal history, and clinical aspects. Histopathology, biological and immunological tests were available in the patients' files. All patients had received treatment, and their progress was recorded in the children's files. Data were entered using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS version 23.

Results

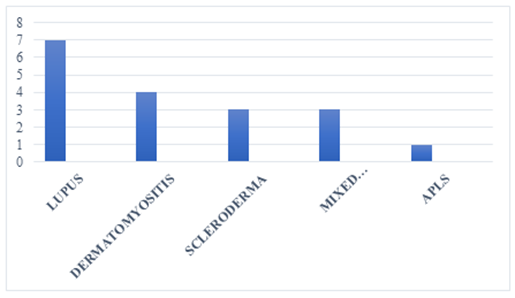

We collected 18 cases of autoimmune systemic diseases in children out of 4986 cases seen during the study period, representing a hospital frequency of 0.36%. The systemic diseases noted were, in descending order, lupus in 7 cases, dermatomyositis in 4 cases, scleroderma in 3 cases, mixed connectivity in 3 cases, and APLS in 1 case. The distribution of patients by connective tissue type is shown in Figure 1. The mean age of the children was 10 years, with extremes ranging from 4 to 14 years. The children were female in 16 cases (88.9%) and male in 2 cases (11.1%), giving a sex ratio of 0.12.

Figure 1: Distribution of cases according to connectivitis type.

Lupus in children

The seven children with lupus were female and had an average age of 10 years, with extremes of 6 and 14 years. The cutaneous manifestations of lupus were acute lupus (figure 2) in 5 cases (71.43%), subacute lupus in 1 case (14.28%), and chronic lupus in 1 case (14.28%). Table 1 illustrates the various dermatological manifestations of lupus in children. Visceral involvement included joints in 6 cases, kidneys in 2 cases, and cardiovascular disease in one case. Anemia was noted in 5 cases, and anti-Sm antibodies were positive in 3 cases, anti-DNA antibodies in 2 cases, and antinuclear antibodies in one case. All children had received corticosteroid therapy at 1 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day with adjuvant treatment associated with hydroxychloroquine at 6.5mg/kg/per day. Two children received azathioprine at 1.5 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day. Complete clinical remission was noted in 4 cases, a new relapse in 2 cases and death was noted in one child followed for lupus nephropathy.

Table 1: Dermatological manifestations of lupus

| Type of lupus | Clinical signs | Number | Percentage (%) |

| Acute lupus | erythema vespertilio on the face | 4 | 57,1 |

| photosensitivity | 4 | 57,1 | |

| Erythema of photoexposed areas | 3 | 42,9 | |

| Infiltrated papules face/ trunk | 1 | 14,3 | |

| Non –scarring alopecia | 1 | 14,3 | |

| gluteal calcinosis | 1 | 14,3 | |

Subacute lupus

| Ring-shaped plaques (trunk, back, limbs) | 1 | 14,3 |

| Infiltrated erythematous lesions | 1 | 14,3 | |

| Chronic lupus | generalized erythematous scaly patches | 1 | 14,3 |

| Scarring alopecia | 1 | 14,3 | |

| Atrophy | 1 | 14,3 |

Figure 2: Acute lupus in a 13-year-old girl

Dermatomyositis in children

Four girls were involved, with an average age of 10 and extremes of 4 and 13 years. Facial erythema and Gottron papules were characteristic features (Figure 3). Dermatological manifestations of dermatomyositis are shown in Table 2. Extra cutaneous involvement included myalgia in 4 cases, polyarthritis in 3 cases, cardiomyopathy in 3 cases, and interstitial lung disease in 2 cases. Muscle enzymes were elevated in 5 cases, and anti-MDA5 antibodies were positive in one. The children had received oral corticosteroid therapy with prednisone at 1 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day in 4 cases, hydroxychloroquine 6.5 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day, and mycophenolate mofetil in 1 case. Complete clinical remission was noted in 2 cases, a relapse in one, and one child died at home.

Table 2: Dermatological manifestations of dermatomyositis

| Clinical sign | Number | Percentage (%) |

| Periorbital erythroedema | 4 | 100 |

| Ulcero-necrotic lesions on the face/forearm | 3 | 75 |

| Atrophic lesions in exposed photo areas | 2 | 50 |

| Non-scarring alopecia | 2 | 50 |

| Non-erosive cheilitis | 2 | 50 |

| Poikiloderma on face/forearm | 1 | 25 |

| Gottron papules of the hands | 1 | 25 |

| Calcinosis of elbows | 1 | 25 |

Figure 3: Facial erythema and Gottron papules in a 6-year-old girl.

Scleroderma in children

It involved two girls and a boy, with a mean age of 10 years and extremes of 7 and 12 years. Cutaneous sclerosis (Figure 4) was the predominant sign. The dermatological manifestations of scleroderma in children are illustrated in Table 3. There was no visceral involvement. Inflammatory anemia at 10g/dl was noted in one case. Corticosteroid therapy was administered at 0.5mg/kg/per day in 3 cases. Calcium channel blocker (nifedipine) 0.25 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per dose in 2 cases, methotrexate 10mg/week in one case. Clinical remission was noted in 2 cases, and a new relapse was secondary to a therapeutic breakthrough in one case.

Figure 4: Systemic scleroderma in a 12-year-old child

Table 3: Dermatological manifestations of scleroderma

| Clinical sign | Number | Percentage (%) |

| Sclérodactyly | 3 | 100 |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 3 | 100 |

| Finger edema | 2 | 66,7 |

| Cutaneous sclerosis | 2 | 66,7 |

| Nail cuticle hypertrophy | 1 | 33,3 |

| Stellar pulp scars | 1 | 33,3 |

| Speckled achromia | 1 | 33,3 |

| Digital necrosis | 1 | 33,3 |

Figure 5: Toe necrosis in a child with APLS.

Mixed connectivity in children

Lupus was associated with dermatomyositis in 2 cases, and lupus with APLS in one case. The mean age of the children was 12 years, with extremes of 9 and 13 years. Clinical manifestations are illustrated in Table 4. Anti-Sm, antinuclear, and phospholipid antibodies were positive. The children had received corticosteroid therapy at 1 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day in 3 cases, azathioprine in one case, hydroxychloroquine in 3 cases, and an anticoagulant in one case.

Table 4: Dermatological manifestations of mixed connectivity

| Clinical sign | Number | Percentage (%) |

| Erythema (vespertilio) of the face | 2 | 100 |

| Erythema of light –exposed areas | 2 | 100 |

| Oral ulcers | 2 | 100 |

| Periorbital erythema | 1 | 50 |

| Annular lesions | 1 | 50 |

| Palmoplantar purpura | 1 | 50 |

| Nail hemorrhage | 1 | 50 |

| Infiltrated annular plate of the face | 1 | 50 |

| Cicatricial alopecia | 1 | 50 |

Children's APLS

The case involved an 11-year-old boy with a history of congenital heart disease who presented with a necrotic ulcer of the foot and cyanosis of the toes and fingers. He had no extracutaneous clinical signs. His blood count cells were normal, and he had no coagulation inhibitor deficiencies (protein S, C, anti-prothrombin III). Anti-phospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anti-B2Gp, anticardiolipin) were positive at 12-week intervals. He had received anticoagulants, digitalis, diuretics, and undergone surgical necrosectomy. The course was favorable, with complete healing and clinical remission.

Discussion

We report 18 cases of systemic autoimmune disease in children, with a hospital frequency of 0.3%. Systemic lupus and dermatomyositis were the most frequent systemic autoimmune diseases in children. This low incidence is also reported in Europe at 0.22 cases per 105 children [12]. A predominance of girls with an average age of 10 years was noted in our study. These findings are also reported in the majority of publications on childhood systemic diseases [13, 14,15]. In childhood lupus, we noted polymorphous cutaneous manifestations, with a predominance of acute lupus lesions associated with renal involvement in 2 cases. It was Vespertilio erythema of the face, photosensitivity, erythema of photo-exposed areas, and infiltrated papular lesions. Renal involvement is a more frequent severity factor than in adults and was glomerulonephritis in our study [16]. According to Levy, it is 30-80% more prevalent than in adults [17]. Anti-Sm antibodies were positive in 3 cases (37.5%). Their positivity rate in systemic lupus ranges from 11 to 45%, and they are specific to lupus [18]. Anti-DNA antibodies were positive in 2 cases (28.6%) and often correlate with disease activity and progression, and are sometimes associated with renal involvement [19]. Corticosteroid therapy was the first-line treatment for lupus, at 1 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day, gradually tapering off to 5 mg/per day. Hydroxy-chloroquine was combined with corticosteroids in all children. Immunosuppressants were administered in 2 cases during the decreasing of oral corticosteroids.

In dermatomyositis, the predominant cutaneous signs in our study were palpebral erythroedema, necrotic ulceration, Gottron's papules, and calcinosis. In children, cutaneous calcinosis is a frequent feature of dermatomyositis. They occur in 20 to 40% of cases [20,21]. Muscle involvement was present in all children, with a major impact on quality of life. Interstitial lung disease and cardiomyopathy were the main visceral disorders. These often occur in 50% of children, with a prevalence of 8% [22,23]. No association with cancer was noted. Anti-MDA5 antibodies were positive in one case and were associated with interstitial lung disease in our study. According to some authors, their positivity is often associated with severe muscle damage, dysphagia and edema [24,25]. In childhood scleroderma, acral cutaneous sclerosis was the most frequent clinical manifestation, followed by Raynaud's syndrome and pigmentary disorders. Visceral involvement was mainly cardiac and pulmonary in 33%. Anti-ECT antibodies were normal. Corticosteroids were used at 0.5 mg per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day in combination with methotrexate in one case, with a favorable outcome. Progressive relapses were secondary to a therapeutic break due to the parents' limited financial resources.

The lupus-dermatomyositis association was more frequent, as was one case of lupus-APLS. Cutaneous manifestations combined signs of both systemic diseases, with polymorphous cutaneous lesions. The children had no visceral involvement. The evolution was favorable with corticotherapy, an synthetic antimalarials drugs, and anticoagulants in one case.

Only one child had confirmed isolated APLS. Necrotic ulcerations were the primary finding. Other authors report the frequency of reticular livedo and Raynaud's phenomenon [26]. In terms of treatment, corticoids an synthetic antimalarials drugs, and Immunosuppressive drugs are the molecules most commonly used in our study, due to their availability and accessibility at the lowest cost. Biotherapies are expensive and not yet accessible to our patients with limited resources. The evolution was generally good, with prolonged clinical remission. Mortality in our study was essentially related to visceral renal and cardiac damage.

Conclusion

The Systemic autoimmune diseases of children are dominated by lupus, dermatomyositis, mixed connectivities, and APLS in dermatology departments in Dakar. They are unique in that they occur frequently in girls, with an average age of 10, and are characterized by clinical polymorphism, severe visceral involvement, and the absence of associated neoplasia. Corticosteroid oral therapy is still the first-line treatment, together with Immunosuppressive drugs. The advent of biotherapies in Africa would help improve the prognosis of children refractory to conventional treatments in our regions.

References

- Michel M, Godeau B. (2005). Complications infectieuses des maladies systémiques. Réanimation, 14:621-628.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Combe B. (2007). Des maladies auto-immunes aux « IMID » en passant par les syndromes auto-inflammatoires. Rev Rhumatisme, 74:711-713.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Trindade C V, Carneiro‑Sampaio M, Bonfa E, Clovis A S. (2021). An Update on the Management of Childhood‑Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Pediatric Drugs, 23:331-347.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Harry O, Yasin S, Brunner H. (2018). Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Review and Update.J Pediatr, 196:22-30.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hetlevik SO, Flato B, Rygg M, Nordal EB, Brunborg C, Hetland H, Lilleby V. (2017). Long-term outcome in juvenile-onset mixed connective tissue disease: a nationwide Norwegian study. Ann Rheum Dis. 76(1):159-165.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Li SC. (2018). Scleroderma in Children and Adolescents : Localized Scleroderma and Systemic Sclerosis. Pediatr Clin North Am, 65(4):757-781.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gattorno M, Buoncompagni A, Molinari A.C, Barbano G.C,Morreale G, Stalla F, Picco P, Mori P.G, Pistoia V. (1995). Antiphospholipid antibodies in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile chronic arthritis and overlap syndromes: SLE patients with both lupus anticoagulant and high-titre anticardiolipin antibodies are at risk for clinical manifestations related to the antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology, 34:873-881.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lamini N, Edgard N, Honoré N. (2020). Les Maladies Auto immunes et de Système au Service de Rhumatologie du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Brazzaville. Health Sci Dis, 21(4):138-140.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pétri M, Orbai A M , Graciela S A , Gordon C , Merrill J T , Fortin RP. (2012). Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 64(8):2677-2686.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pinto B, Janardana R, Nadig R, Mahadevan A, Bhatt AS, Raj JM, Shobha V. (2019). Comparison of the 2017 EULAR/ACR criteria with Bohan and Peter criteria for the classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies.Clin Rheumatol, 22.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hoogen F V, Khanna D , Fransen J , Johnson SR , Baron M ,Tyndall A. (2013). Critères de classification de 2013 pour la sclérodermie systémique : une initiative collaborative du Collège américain de rhumatologie et de la Ligue européenne contre les rhumatismes. Ann Rheum Dis, 72(11):1747-1755.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ndiaye M, Diallo M, Diop A. (2013). La maladie lupique chez l’enfant sur peau noire: étude épidémiologique et clinique à Dakar. Nouv Dermatol, 32 :407-409.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Direkrit Chiewchengchol, Ruth Murphy, Steven W Edwards, Michael W Beresford. (2015). Mucocutaneous manifestations in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of literature. Pediatric Rheumatology, 13:1.

Publisher | Google Scholor - S. Maghfour, A. Aounallah, M. Ben Kahla, R. Mesfar, S. Mokni, W. Saidi, R. Gammoudi, N. Ghariani, C. Belajouza, B. Lobna, M. (2019). Denguezli.Sclérodermie systémique juvénile : à propos de 3 cas.Rev Méd Int, 40:141-142.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hartman EAR, van Royen-Kerkhof A, Jacobs JWG, Welsing PMJ, Fritsch-Stork RDE. (2018). Performance of the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria versus the 1997 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria in adult and juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev, 17:316-322.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Leye YM, Ndiaye N, Diack ND, et al. (2017). Aspects épidémiologiques et diagnostiques des connectivites au service de Médecine Interne du CHUN de Pikine: analyse de 287 observations. RAFMI, 4:22‐25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Levy M, Montes DE OCA M, Babron MC. (1989). Incidence du lupus érythémateux dissémine de l’enfant en région parisienne. Presse MED, 18 :20-22.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bader-Meunier B, Haddad E, Niaudet P, Loirat C Leblanc T, Amoura Z, Bodemer C, Cochat P, Deschenes G, Kone- Paut I, Levy-M, Prieur. A.M, Quartier P, Ranchin B Salomon R, Piette J.C. (2003). Lupus érythémateux systémique chez l’enfant. Arch pédiatr, 10:147-157.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Massias JS, Smith EMD, Al-Abadi E, Armon K, Bailey K, Ciur- tin C, et al. (2020). Clinical and laboratory characteristics in juvenile- onset systemic lupus erythematosus across age groups. Lupus, 29:474-481.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Philippi k, Hoeltzel M, Byun Robinson A, Kim S, Abramson LS, Anderson ES et al. (2017). Race, income, and disease outcomes in juvenile dermatomyositis. J. Pediatrics, 184: 38-44.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Melody PC, Richardson C, Kirakossian D, Orandi AB, Saketkoo LA, Rider LG et al. (2020). Calcinosis biomarkers in adult and juvenile dermatomyositis. Autoimmun Rev, 19(6):102-533.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pouessel G, Deschildre A, Le Bourgeois M, Cuisset J-M, Catteau B, Karila C, et al. (2013). The lung is involved in juvenile dermatomyositis: Lung Involvement in Juvenile Dermatomyositis. Pediatric Pulmonology, 48(10):1016-1025.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Enders FB, Bader-MB, Baildam E, Constantin T, Dolezalova P, Feldman BM, et al. (2017). Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Diseases. 76(2):32940.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wu Q, Wedderburn LR, McCann LJ. (2017). Juvenile dermatomyositis: Latest advances. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 31(4):535-557.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Li D, Tansley SL. (2019). Juvenile Dermatomyositis-Clinical Phenotypes. Curr Rheumatol Rep, 21(12):74.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tektonidou MG. (2018). Antiphospholipid Syndrome Nephropathy: From Patho‐ genesis to Treatment. Front Immunol, 31(9):1181.

Publisher | Google Scholor