Research Article

Assessing the Hesitancy of Uptake of Covid-19 Vaccine Among Sars-Cov-2 Infected Individuals in Rural Segments of Haryana

1Program Officer, NLEP, MoHFW, New Delhi, India.

2Student, Masters in Psychology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India.

3Student, Masters of Technology, Chandigarh University, Punjab, India.

*Corresponding Author: Shyam R, Program Officer, NLEP, MoHFW, New Delhi, India.

Citation: Shyam R, Neha G, Anupriya. (2023). Assessing The Hesitancy of Uptake of Covid-19 Vaccine Among Sars-Cov-2 Infected Individuals in Rural Segments of Haryana. International Journal of Nutrition Research and Health, BRS Publishers. 2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2871-6021.brs.23.003

Copyright: © 2023 Shyam R, this is an open-access article distributed under theterms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,distribution, andreproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source arecredited.

Received: February 28, 2023 | Accepted: March 14, 2023 | Published: March 21, 2023

Abstract

Background: COVID-19 started like a viral outbreak in Wuhan in December 2019. It was a new highly contagious disease that caused 693,224 confirmed cases and 33,106 deaths on 30th March 2020 all over the world [1]. As a preventive measure vaccination is one of the biggest achievements of public health [4-8]. Despite an increase in vaccine uptake rate, over time it is observed that some people who were previously exposed to COVID-19 infection are hesitant towards its immunization. This study identifies the possible causes or fear among these groups of individuals and embarks some suggestive measures to counteract such hesitancy.

Aim, objective, Methodology: The aim of the study was to assess the hesitancy of COVID- 19 vaccine among SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals in rural segments of Haryana state. For, this a well-structured pre-tested questionnaire is used to collect the data from a randomly selected group of people (including males and females). This data is later on analyzed and results were obtained by using Microsoft excel. Ethical consent is taken from the district ethical committee along with written consent from the participants of the study.

Results: The results show the relationship between the type of fear among the previously exposedCOVID-19 infected individuals.

Keywords: hesitancy; fear; covid-19; vaccination

Introduction

Outbreak started in Wuhan in December 2019. It is a new highly contagious disease that caused693, 224 confirmed cases and 33, 106 deaths on 30th March 2020 all over the world [1]. Massive preventive measures like face masks, quarantines, and travel restrictions are not alone adequate to control it [2,3]. In such situations, vaccination is one of the biggest achievements of the public health sector [4-6]. Despite an increase in vaccine uptake rate, vaccine hesitancy is the new emerging problem that can be seen among people [5-8]. The world health Organization Strategic Advisory Group of experts defines vaccine hesitancy as refusal or delay in vaccination despite availability. It is a complex and context-specific concept, varies across vaccines, time, and place [9]. Vaccine hesitant people are those who accept certain vaccines while refusing others, accept vaccination but have concerns or delay vaccination. Fear is the natural response to the pandemic situation that can be seen among people. Majorly health anxiety is the major contributor to high refusal rates of vaccination which is also linked to fear of death of a high number of people from vaccine-preventable diseases [10-14]. Over time it is observed that some people who were previously exposed to COVID-19vaccination are hesitant to the second dose of vaccination. It is a new emerging problem in course of complete immunization coverage. Therefore, in such a situation, it is noteworthy that this study aimed to assess fear of vaccine hesitancy among people previously exposed to COVID-19 vaccination in rural sections of Haryana state. For, this study we used a well-structured pre-tested questionnaire to collect the data from a randomly selected group of people (including males and females). The questionnaire contains three sections which include participant consent, demographic details, and COVID-19 fear-related questions.

Literature

During this review, it is observed that Fear is the response to pandemics [10-13]. Overall, vaccination hesitancy significantly increased. In some countries, health-related anxiety is the reason for the decline in vaccination intake [4]. Also, it is observed that people who are previously exposed to the COVID-19 infection tend to show a low rate of vaccination due to certain myths, stigmas, and fears, this may be with a number of deaths post-vaccination. Some studies showed that media play a major role in propagating fear of COVID-19vaccination [14]. Fear is identified as the primary reason for immunization reluctance in parents and children and is related to the perception of getting infected with a virus, lack of knowledge about the advantages of complete immunization [15-19].

Yen and Shaun mentioned in their research article published in 2021 that parents refuse to present their children at clinics as they are anxious about the risk of COVID-19 infection to their children [20]. In another research conducted in the same year, found that only eight parents, or 1.1% of parents hesitated to get a vaccination for their children, and Urban vs. rural parents (69.7%vs. 48.6; p less than 0.0001) thought that parents like them do not have their children vaccinated with all recommended vaccines [21]. Therefore, in these circumstances, complete vaccination coverage is the new problem.

Methodology

Aim: The aim of the study was to assess the hesitancyof COVID-19 vaccineamong SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals in rural segments of Haryana state.

Study area: Village Bohar, Rohtak, Haryana.

Sample size: 111

Study design: A cross-sectional study.

Method: A pre-tested questionnaire was used via Google form to collectthe data from randomly selected people from rural segments of Bohar, Rohtak, Haryana.

Results: Results were compiled usingthe Microsoft-excel in form of graphs and tables.

Ethical clearance: The participant's consent was taken along with the ethicalclearance from the ethical committee.

Exclusion criterion: This study excluded the unavailable, Unwillingand hesitant individuals.

Observations and Results

| Sr. no. | Result | Observation | Associated data table |

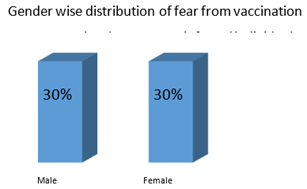

| 1 | Fear of COID-19 vaccination among males and females who were previously exposed to COVID-19 infection. | From data collected. It was observed that the fear of inoculation of the COVID-19 vaccine among both the gendersare equal. | Table 1, Figure 1 |

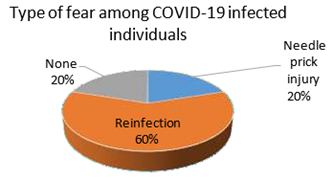

| 2 | Reson of fear form COVID-19 Vaccination amont previously exposedindividuals | The datashows a dramatic result of morefear from reinfection. | Table 2, Figure 2 |

Table 1: Gender wise distribution of fear from vaccination amongpreviously COVID-19 infected individuals.

| Gender wise distribution of fear | Percentage of individuals having fear |

| Male | 30% |

| Female | 30% |

Figure1: Gender wise distribution of fear from vaccination among previously COVID-19 infected individuals.

Table 2: Type of fear among COVID-19 infectedindividuals

| Type of fear | Percentage individuals |

| Needle prick injury | 20% |

| Reinfection | 60% |

| None | 20% |

Figure2: Type of fear among COVID-19 infected individuals

Discussion

World HealthOrganization (WHO) in 2019 identified Covid-19 as pandemic. In the context of control of the COVID-19 pandemic, the emergence of fear of COVID-19 immunization can be seen among people [1]. In some countries, health-related anxiety is the reason for the decline in vaccination intake [4]. This is associated with the high number of deaths due to vaccine interventional disease. In these circumstances, the media played a major role in propagating fear of COVID-19 vaccination. Exposure to misinformation results in a decrease in acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [14]. Vaccine hesitancy results in less COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and barrier to covid-19 vaccine uptake. Fear is identified as the primary reason for immunization reluctance is related to the perception of getting infected with a virus, lack of knowledge about the advantages of complete immunization [15-19]. Apart from these studies, the present study's aim is to assess the fear of vaccine hesitancy among people previously exposed to COVID-19 infection in rural sections of Haryana state.

For, this study we used a well-structured pre-tested questionnaire was used to collect the data from a randomly selected group of people (including males and females). The questionnaire contains three sections which include participant consent, demographic details, and COVID- 19 fear-related questions. For this study ethical consent was taken from the district ethical committee as well as the individual participants. The Unwilling, no available, and reluctant participants were excluded from the study. The Collected data were analysed by using Microsoft excel to obtain results. The results dramatically show that both males and females have an equal sense of fear towards the COVID-19 vaccination. Most people have fear irrespective of the type of vaccine in form of Needle prick injury, chances of reinfection and few have the fear of other possible side effects.

Conclusion

In the present study,we concluded that fear is widespread amongrural people of Haryana who were previously exposed to COVID-19infection. Females and Males show unexpectedly more fear of reinfection than any other.

Key Recommendations

More of the IEC activity needs to be done along with the principle of role model such as a person who is previously infected with COVID-19 and completes all doses of vaccination.

The boost of the immunization coverage with special emphasis on eliminating the myths and stigmas related to the COVID-19 vaccination.

References

- health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sherman, S. M, Smith, L. E, Sim, J (2021). COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutic. 17(6):1612-1621.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mejia, C. R, Rodriguez-Alarcon, J. F, Vera-Gonzales.et.al (2021). Fear Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 18(3).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bendau, A, Plag, J, Petzold, M. B, & Ströhle, A. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and related fears and anxiety. International immunopharmacology. 97:107-724.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dzinamarira, T, Nachipo, B, Phiri, B. & Musuka, G. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine rollout in South Africa and Zimbabwe: urgent need to address community preparedness, fears and hesitancy. Vaccines. 9(3):250.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lurie, N. Saville, M. Hatchett, R. & Halton, J. (2020). Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. New England Journal of Medicine. 382(21):1969-1973.

Publisher | Google Scholor - CoV-2 vaccine based on experimental results from similar coronaviruses. International immunopharmacology, 86:106-717.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Boddice, R. (2016). Vaccination, fear and historical relevance. History compass. 14(2):71-78.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2012). Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, SAGE (WHO).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R et.al. (2013). Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 9(8):1763-1773.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gowda C, Dempsey AF. (2013) The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 9(8): 1755-1762.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. (2014) Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 32(19):2150-2159.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. (2014) Attitudes to vaccination: A critical review. Soc Sci Med. 112:1-11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ropeik D (2013). How society should respond to the risk of vaccine rejection. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics.9(8):1815–1818.

Publisher | Google Scholor - H.J. Larson, A. de Figueiredo, Z. Xiahong, W.S. Schulz, P. Verger, I.G. Johnston, et al. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country surve EBioMedicine.12 :295-301.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Loken, E. K. Hettema, J. M. Aggen, S. H. & Kendler, K. S. (2014). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for fears and phobias. Psychological medicine. 44(11):2375-2384.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muris, P., Schmidt, H., & Merckelbach, H. (1999). The structure of specific phobia symptoms among children and adolescents. Behaviour research and therapy, 37(9):863-868.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wenzel, A., & Holt, C. S. (2003). Validation of the Multidimensional Blood/Injury Phobia Inventory: evidence for a unitary construct. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 25(3):203-211.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Taddio, A. Ipp, M. Thivakaran, S. Jamal, A. Parikh, C. Smart, S. & Katz, J. (2012). Survey of the prevalence of immunization non-compliance due to needle fears in children and adults. Vaccine. 30(32):4807-4812.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wong, Y. J. & Lee, S. W. H. (2021). COVID-19: A call for awareness or mandatory vaccination even in pandemics? Journal of Global Health, 11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gretchen J. Domek, Sean T. O'Leary, Sheana Bull, Michael Bronsert, Ingrid L. et.al (2018).Measuring vaccine hesitancy: Field testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy survey tool in Guatemala, Vaccine,Volume (36) 35:5273-5281.

Publisher | Google Scholor