Review article

Are Tribal People in India Relatively more Susceptible to Fluorosis? More Research is Needed on this

1Department of Advanced Science and Technology, National Institute of Medical Science and Research, India.

2Department of Prosthodontics and Crown & Bridge, Geetanjali Dental and Research Institute, Udaipur, India

3Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, RNT Medical College and Pannadhay Zanana Hospital, Udaipur, India.

*Corresponding Author: Shanti Lal Choubisa, Department of Advanced Science and Technology, National Institute of Medical Science and Research, India

Citation: Shanti L. Choubisa, Choubisa D., Choubisa P. (2023). Are Tribal People in India Relatively more Susceptible to Fluorosis? More Research is Needed on this, Pollution and Community Health Effects, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 1(3):1-10. DOI: 10.59657/2993-5776.brs.23.013

Copyright: © 2023 Shanti Lal Choubisa, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: October 31, 2023 | Accepted: November 23, 2023 | Published: November 28, 2023

Abstract

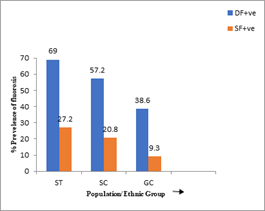

Endemic fluorosis in humans, a major health issue that is the resultant of prolonged exposure fluoride through drinking of water having fluoride over 1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm or/and industrial fluoride pollution. Millions of people worldwide are found suffering from fluorosis. In this disease, people's teeth and bones are adversely affected. Teeth become weak, discolored and fall out at an early age (dental fluorosis) while various bones become porous, weak and deformed (skeletal fluorosis) and most people become hunchbacked and lame. During fluorosis, many health complaints are also developed, such as gastrointestinal discomforts, polydipsia, polyuria, impaired reproductive and endocrine systems, neurological disorders, etc. However, the prevalence and severity or susceptibility of fluorosis depends on certain determinants other than fluoride level and its duration and frequency of exposure. Nevertheless, genetics of individuals has also association with susceptibility to fluorosis which was also observed in a large-scale study conducted in 18621 subjects belonging to Scheduled Tribe (ST), Scheduled Caste (SC), and General Caste (GC) residing in the Scheduled area of Rajasthan, India. The study revealed that the prevalence of dental and skeletal fluorosis was found to be higher among tribal people (69.0% and 27.7%, respectively) than among SC (57.2% and 20.8%, respectively) and GC (38.6% and 9.3%, respectively) population. These findings indicate that subjects' genetics also have a contributing role in susceptibility to fluoride toxicity. However, more research is still needed on this aspect for confirmation. The current review focuses on why tribal people are relatively more susceptible to fluorosis. Additionally, research gaps for further study are also highlighted.

Keywords: chronic fluoride exposure; dental fluorosis; determinants; fluorosis; genetics; hydro fluorosis; intoxication; non-skeletal fluorosis; skeletal fluorosis; susceptibility; tribals

Introduction

Water-borne fluorosis disease in humans is a major health issue that is more prevalent and endemic in regions where drinking water is contaminated with fluoride. Generally, it appears when people drink water containing fluoride more than the permissible or recommended value of 1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm [1-3]. But there is a condition that the fluoride exposure should be for a long time. The disease appears rapidly if the exposure frequency is high. In this endemic disease, not only teeth and bones of people are affected but various soft tissues or organs are also affected [1]. In general, chronic fluoride intoxication or fluorosis is manifested as dental fluorosis with the appearance of yellowish to brownish striations or mottling of teeth, and/or skeletal fluorosis where osteosclerosis, ligamentous and tendinous calcification, and extreme bone deformity result [4-8]. Due to fluoride toxicity, teeth of people of all age groups become weak and fall out at an early age, while various skeletal bones become porous, brittle, and deformed with varying grades. This disease is not only limited to humans but is also found in various species of herbivorous animals that drink fluoridated water for a long time [9-29]. Fluorosis is endemic in more than 25 countries around the world [1]. Among these, China and India are most affected. The disease is affecting millions of people worldwide, although no accurate worldwide data exists on the total number affected. However, few numbers are available at the national level. In China, 38 million people are reported to have dental fluorosis and 1.7 million people have skeletal fluorosis [30]. In India, approximately 10 lakh people suffer from severe and disabling skeletal fluorosis [31]. However, the authors believe that even more people may be suffering from fluorosis in these countries at this time.

In India, especially in rural areas, drinking groundwater is found to be contaminated with fluoride to varying degrees [32]. Therefore, fluorosis (hydro fluorosis) is endemic in rural areas of almost every state. Thousands of villagers and their pets suffer from various types of fluorosis (dental, skeletal and non-skeletal fluorosis) [33]. However, it is expected that no such study on fluorosis in people of different caste/ethnic groups or populations of the same fluoride endemic area with almost similar environment in other states of India except the state of Rajasthan has been conducted so far. Such studies have not yet been conducted in other countries of the world. Indeed, the varying prevalence and severity of fluorosis in people belonging to different race or caste categories and populations indicates that certain determinants are responsible for influencing fluoride toxicity or susceptibility/vulnerability. But the genetics of humans belonging to different populations also influence fluoride toxicity to some extent which is the focus of the present review. Additionally, research gaps for further study are also highlighted.

Scheduled Areas and Tribes in Rajasthan

In India, Rajasthan is the largest state and is divided by the Aravalli Mountains into two eco-geographically distinct regions, desert and humid, located in the western and eastern parts respectively. Out of its 33 districts, eight districts namely Banswara, Chittorgarh, Dungarpur, Pali, Pratapgarh, Rajsamand, Sirohi, and Udaipur districts have been included in the "Scheduled Area" [34]. This region is the most backward, underdeveloped, and deprived and is characterized by the predominance of various ethnic groups of tribes or tribal communities or populations. According to 2011 census, the total population of the Scheduled Area is 64, 63,353, out of which the scheduled tribe population is 45, 57, 917 which is 70.43% of the total population of the Scheduled Area. The most dominant endogamous tribes in the Scheduled Area are the Bhils, Damors, Meenas, Garasiyas, Kathudias, and Sahariyas [34].

The socio-economic condition of tribal subjects in the Scheduled Areas is very poor and their literacy rate is relatively very low. Health education among the tribals is also almost negligible. Generally tribal people prefer to live isolated in forest areas. Economically the tribal people are dependent on animal husbandry, traditional agriculture, and forest produce. The nutritional status of tribal people is also very poor. The main foods in their diet are maize, barley, rice, onion, garlic, and pulses with or without vegetables. Sometimes, they consume meat, milk, curd, cooking oil, ghee, seasonal fruits and vegetables. Most tribals are accustomed to consuming locally produced liquor, tea, smoking and tobacco, while youth of both sexes often consume betel nuts (betel nuts) and tobacco-flavoured Pan Masala and Gutkha. In general, tribal people are shy, conservative, highly conservative and superstitious and have deep faith in their local deities and believe that they will keep them healthy and away from various diseases. Mostly, tribal people use their traditional methods to treat various diseases including fluorosis [34].

Sources of fluoride exposure for tribals in Scheduled Area

It is well known that fluoride is present in varying levels in water, food, soil, and air [1]. A large number of natural and anthropogenic sources of fluoride exposure are found in the Scheduled Areas. However, the most common and major source of fluoride exposure for tribal individuals and their pets is groundwater [35-39]. In the tribal villages of the Scheduled Area, ground water of almost all drinking water sources (hand-pumps and bore-wells) is contaminated with fluoride and contains fluoride more than the maximum permissible limit (1.0 or 1.5 ppm) as per WHO (World Health Organization), ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research), and BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards) standards [1-3]. Excessive consumption of such fluoridated water and its use in cooking over a long period of time leads to poor tribal health and various adverse health consequences such as fluorosis [32].

Fluoride in drinking groundwater in the Scheduled Area of Rajasthan ranges between 0.1-21.6 ppm [35-39]. In Banswara, Chittorgarh, Durgapur, Pali, Pratapgarh, Rajsamand, Sirohi, and Udaipur districts, fluoride content in drinking water is found in the range of 0.1-4.6 ppm, 0.0-6.6 ppm, 0.1-10.8 ppm, 0.0-14.0 ppm, 0.0-14.0 ppm, 0.0-14.0 ppm, 0.0-14.0 ppm, 0.0-14.0 ppm, and 0.0-14.0 ppm. ppm, 0.1-4.7 ppm, 0.0-4.5 ppm, 1.0-16.0 ppm, and 0.1-21.6 ppm, respectively [35-39]. Prolonged exposure to such fluoridated water is not safe and harmful to human and animal health [40-42].

In addition to fluoride in drinking water, fluoride is also found in various food chains and webs as well as in agricultural or crop yields (food grains, cereals, pulses, vegetables, fruits, etc.) cultivated in fluoride-rich soils and is irrigated by fluoride-rich groundwater [43]. In Scheduled Area, domesticated animals also suffer from chronic fluoride intoxication in the form of fluorosis [44-49]. Therefore, milk and meat of these fluoridated animals contain varying levels of fluoride and are a source of fluoride exposure for tribal subjects [50-54]. Apart from these, alcohol, tea, smoking, and tobacco and betel nuts (betel nuts) including flavored Pan Masala and Gutkha are also potential sources of fluoride exposure for tribal people is as these items contain substantial amounts of fluoride [55]. There are some industries in tribal rural areas which release fluoride in the environment like Hindustan Zinc Smelter, Superphosphate Fertilizer Plant, Rock Phosphate Mining, Chemical Fertilizer, Brick Kiln, Cement Production, etc. All of these are potential sources of fluoride exposure for tribal people and their domesticated animals also [56-60].In fact, these industries release fluoride in gaseous and particulate/dust form into the surrounding environment and pollute soil, agricultural crops, vegetation, and freshwater reservoirs. Inhalation of fluoride is relatively more dangerous and harmful to both human and animal health.

Fluorosis in Inhabitants of Scheduled Area

It is well established that excessive intake and inhalation of fluoride for prolonged period causes mild to severe fluorosis disease. Fluoride has the potential to affect or damage teeth and bones as well as various soft tissues or organs. Once fluoride enters the body, it is absorbed by the digestive and respiratory systems and ultimately reaches various organs through the blood circulatory system. More than 50% of the absorbed fluoride is excreted through excretion and sweat, while the rest is retained in the body and gradually accumulates in teeth and bones and also in soft organs. But because of its greater proximity to calcium, it is most deposited in the calcified tissues of bones and teeth than in non-calcified tissues or organs. Excess accumulation of fluoride interferes with physiology or metabolic processes which ultimately causes various adverse changes or toxic effects in the body. These fluoride-induced pathological changes are collectively called fluorosis. These changes to the teeth and bones are usually permanent, irreversible and not treatable and can be seen with the naked eye. However, changes in soft tissues are reversible and disappear upon removal of the source of fluoride exposure. If these fluoride-induced changes are caused by excess consumption of fluoridated water either through drinking and cooking, they are collectively known as hydro fluorosis, which is more common and widespread not only in the tribal people but also in their pet animals of the Schedule Area of Rajasthan [6,32]. When these changes occur as a result of exposure to industrial fluoride pollution, they are known as neighborhood and industrial fluorosis in humans and domestic animals, respectively [56-59]. Both forms of fluorosis are prevalent and highly endemic in the Scheduled Areas of Rajasthan.

In Scheduled Area, at 2.5 ppm fluoride level in drinking water, 100% tribal people were found to be suffering from dental fluorosis [37]. In dental fluorosis, tribal individuals have dental mottling or bilateral horizontal opaque brownish pigmented streaks on the teeth (Figure 1). This is an early clinical or pathognomic sign of chronic fluoride intoxication [8, 29]. In a large survey study conducted in various tribal villages of Scheduled Area where fluoride in drinking water was between 0.1 and 21.6 ppm. The study revealed that out of 9429 tribal children and 10315 adolescents and old tribal subjects, 6496 (68.8%) and 7472 (72.4%) were found to have dental fluorosis, respectively [37,60].

Figure 1: Histogram showing the prevalence of fluorosis in subjects belonging to scheduled tribe (ST), scheduled caste (SC), and general caste (GC) populations or ethnic groups of Scheduled Area of Rajasthan, India. Source: [74]

Excessive fluoride intake leads to various bone deformities called skeletal fluorosis, which is very painful and more dangerous than dental fluorosis. Skeletal fluorosis is of utmost importance as it reduces mobility at a very early age by causing gradual progressive changes in bones such as periosteal exostosis, osteosclerosis, osteoporosis, and osteophytosis [62-65]. These changes manifest clinically as vague pain in the body and joints and these changes can be seen and identified in radiographs of various bones of people suffering from skeletal fluorosis. Excess accumulation of fluoride in the muscles also reduces or restricts movements and the condition leads to handicap or crippling and neurological complications such as paraplegia and quadriplegia and syndromes of genu-valgum and genu-varum. This is the worst form of skeletal fluorosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sever dental fluorosis in tribal individuals. Tribal children showing pitting or patches fine dots and bilateral stratified deep brownish yellow streaks on teeth (Fig. a-c). Excessive abrasions of enamel and exposure of cementum, and dentine material with deep-brownish staining (Fig. d and e).

In the Scheduled Area, at or above concentrations of 3.0 ppm fluoride in drinking water, most of the tribal people are found crippled and bed-ridden, suffering from hunched-back (kyphosis) and bow-legged (genu-varum) deformities. However, cases of scissor shape, knock-knee (genu-valgum) foot deformities [7], and neurological complications (paraplegia and quadriplegia) are also prevalent in tribal subjects of both sexes (Figure 2). The maximum prevalence of skeletal fluorosis among tribal individuals was found to be 51.5% at 2.5 ppm fluoride concentration in drinking water. In a large survey study being conducted in Scheduled Area villages, where fluoride in drinking water ranges between 0.1 and 21.6 ppm, more than 27% of tribals were found to be suffering from skeletal fluorosis [37, 60]. In the Scheduled Area of Rajasthan, the most common skeletal deformity among tribal people of all age groups is hunch- bow legs (genu-varum syndrome) and the rarest is knock-knee (genu-valgum syndrome). Interestingly, this syndrome has subsequently been found to be more prevalent among the tribals of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh states [66-68]. Why this syndrome is not endemic among the tribals of Rajasthan is not yet clear. However, more research needs to be done on tribals from different areas with different fluoride concentrations in drinking water to know the exact reason behind this difference.

In addition to teeth and bone deformities, the most common fluoride-induced health consequences or problems are, such as intermittent diarrhea or constipation, abdominal pain, flatulence, hives, polyuria and polydipsia, reduced memory, learning ability, intelligence quotient (IQ), cognition, frequent miscarriages, infertility, reluctance to perform reproductive functions, and erectile dysfunction in men are also found in tribal subjects with fluorosis [6, 69-73]. These fluoride-induced changes in soft organs are generally known as non-skeletal fluorosis and are the first signs of chronic fluoride intoxication in both humans and animals [8, 29]. These health consequences are temporary and are not found in a single fluorosis patient.

Are Tribal Individuals Relatively More Susceptible to Fluorosis?

There is no doubt that tribal people are relatively more susceptible or vulnerable to chronic fluoride toxicity. Similarly, children and breastfeeding or lactating mothers are also highly susceptible to fluorosis which is linked to low levels of calcium in them [55]. In India, a large survey study was conducted among 18662 and 8808 subjects of both sexes belonging to Scheduled Tribe (ST), Scheduled Caste (SC), Other Backward Class (OBC), and General Caste (GC) populations of Scheduled Area of Rajasthan for the prevalence and severity of osteo-dental fluorosis [37, 74]. The sources of drinking water in this area are hand- pumps and bore- wells and the water from these sources had fluoride in the range of 0.1-21.6 ppm [35-39]. The findings of this study reveal that the prevalence and severity of fluorosis is relatively higher in tribal subjects compared to subjects from other or non-tribal populations (Tables 1 and 2). The highest prevalence of dental fluorosis (69%) and skeletal fluorosis (27.02%) was found in subjects from ST population, followed by SC, OBC, and GC population (Table 1). These findings are also presented in Figure 3. It is clearly evident that tribal people have lower tolerance and are relatively more sensitive to fluoride. That is why tribal people in the Scheduled Areas of Rajasthan are seriously suffering from fluorosis. Interestingly, other studies conducted on tribal and non-tribal subjects living in different villages, whose drinking water has almost the same fluoride content, revealed a relatively higher prevalence and magnitude of fluorosis in tribal subjects [37, 60]. The high sensitivity and low tolerance to fluoride toxicity among tribal people is mainly due to their poor nutritional status [75].

Figure 3: Tribal individuals suffering with severe skeletal fluorosis having diverse bone deformities, such as kyphosis, invalidism, genu-varum (outward bowing of legs at the knee), genu-valgum (inward bowing of legs at the knee), crossing or scissor-shaped legs (Fig. a and b) and crippling with paraplegia and quadriplegia (Fig. c).

Table 1: Prevalence (%) of dental and skeletal fluorosis in subjects belonging to scheduled tribe (ST), scheduled caste (SC), general caste (GC) populations of Scheduled Area of Rajasthan, India where fluoride in drinking waters is >1.0 mg/l. Source: [74], Figures in parentheses indicate percentage. Correlation coefficient between populations and dental and skeletal fluorosis, r = + 1 (highly positive), * total individuals (Children + adults), ** only adults

| Population | Dental fluorosis | Skeletal fluorosis | ||||

| Dungarpur district | Udaipur district | Total | Dungarpur district | Udaipur district | Total | |

| ST | 5946/7619(78.0) | 1568/3267(47.8) | 7614/10886(69.0) | 1152/3601(31.9) | 248/1545(16.0) | 1400/5146(27.2) |

| SC | 908/1204(75.4) | 638/1496(42.6) | 1546/2700(57.2) | 174/570(30.5) | 92/708(12.9) | 266/1278(20.8) |

| GC | 1236/2382(51.8) | 708/2653(26.6) | 1994/3035(38.6) | 138/1125(12.2) | 84/1256(6.6) | 222/2381(9.3) |

| Total | 8090/11205(72.1) | 2914/7416(39.2) | 11004/18621*(59.0) | 1464/5296(27.6) | 424/3509(12.0) | 1888/8805**(21.5) |

It is well known that apart from fluoride concentration, some other determinants also affect fluoride toxicity. The frequency and duration of fluoride exposure are major factors in the severity of fluorosis. However, age, sex, habits, nutrition and other food components, chemical components of drinking water, environmental factors, individual susceptibility, biological response and tolerance are also determinants of fluorosis [74-81]. Nevertheless, the severity of fluorosis varies greatly depending on the density and rate of bioaccumulation of fluoride in the body [82]. But when other determinants remain the same, the genetic background of individuals can play a major contributing and significant role in influencing the risk of fluorosis. Therefore, an association between genetic polymorphisms in candidate genes and differences in susceptibility patterns of different types of fluorosis among individuals living in the same region or the influence of individual genetics in susceptibility to fluorosis cannot be ruled out. Several studies also indicate that genetic variants or genes such as COL1A2 (collagen type 1 alpha 2), CTR (Calcitonin receptor gene), ESR (Estrogen receptor gene), COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), GSTP1 (Glutathione S-transferase pi1), MMP-2 (Matrix metallopeptidase 2), PRL (Prolactin), VDR (Vitamin D receptor) and MPO (Myeloperoxidase) may increase or decrease the risk of fluorosis [83]. However, more scientific studies are still needed to confirm the association of genetics with susceptibility to fluorosis in subjects belonging to different populations (ST, SC, OBC, GC, etc.) or ethnic groups in India.

The prevalence and severity of fluorosis among tribal people is relatively higher than that of non-tribal people, which is also due to certain nutrient deficiency and some bad habits in tribal people. In fact, their diets contain insufficient amounts of the nutrients, such as calcium and vitamin C that are antidotes to fluoride toxicity [75,77]. Most of the tribal people in the Scheduled Area are also addicted to local liquor, tea, smoking, and regular consumption of tobacco and betel nut containing Pan-Masala and Gutkha. These food items are additional sources of fluoride exposure because they contain a high amount of fluoride [55] which accelerate or aggravates fluorosis. Therefore, tribal people suffer severely from fluorosis at a very young age [84-89]. General awareness in tribal people, providing healthy foods, and fluoride- free water are needed or highly suggestive for prevention and control of fluorosis in the Scheduled Area of Rajasthan [8]. Fluoride- free water in scheduled area can also be provided from surface water sources or by rain water conservation or adopting the Nalgonda defluoridation technology. This technology is ideal and can be used at both household and community levels [90].

Table 2: Severity of dental and skeletal fluorosis in subjects belonging to different populations inhabiting Scheduled Area of Rajasthan, India. Source: [74]

| Population | Dental fluorosis (DF) | Skeletal fluorosis (SF) | ||||||||

DF +ve subjects | Quest- ionable | Very Mild |

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe | SF +ve subjects | Grade | |||

| I | II | III | ||||||||

| ST | 7534/10886 (69.0) | 951 (12.6) | 1229 (16.3) | 1507 (20.0) | 1713 (22.7) | 2114 (28.1) | 1400/5146 (27.02) | 292 (20.8) | 348 (24.8) | 760 (54.2) |

| SC | 1546/2700 (57.2) | 213 (13.7) | 239 (15.4) | 299 (19.3) | 414 (26.7) | 381 (24.6) | 266/1278 (20.80) | 61 (22.9) | 82 (30.8) | 123 (46.2) |

| GC | 1944/5035 (38.6) | 285 (14.6) | 306 (15.7) | 554 (28.4) | 429 (22.0) | 370 (19.0) | 222/2381 (9.32) | 81 (36.4) | 68 (30.6) | 73 (32.6) |

| Total | 11004/186621 (59.0) | 1449 (13.1) | 1774 (16.1) | 2360 (21.4) | 2556 (23.2) | 2865 (26.0) | 1888/8808 (21.4) | 434 (22.9) | 498 (26.3) | 956 (50.6) |

Conclusion

Several studies confirm that the prevalence and severity of endemic fluorosis in tribals of India is relatively higher than in subjects of non-tribal populations. Though, several determinants or factors besides the fluoride concentration and its frequency and duration of exposure such as age, sex, habits, nutrition, chemical components of water, environmental factors, individual susceptibility, biological response and tolerance are influencing the prevalence and severity of chronic fluoride poisoning or fluorosis. However, in addition to these factors, genetics of tribal people is also influencing the fluoride toxicity or susceptibility to fluorosis. Nevertheless, more scientific studies are still needed to confirm the association or impact of genetics with susceptibility to fluorosis in tribal individuals.

Declarations

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

Funding sources

No funding source for this work.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Vishwajit Jaroli, Head of the Department of Zoology, Shri Ratanlal Kanwarlal Patni Girls College, Kishangarh, Rajasthan 305801, India, for his kind cooperation.

References

- Adler P, Armstrong WD, Bell ME, Bhussry BR, Büttner W, et al. (1970). Fluorides and human health. World Health Organization Monograph Series No. 59. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Publisher | Google Scholor - ICMR. (1974). Manual of standards of quality for drinking water supplies. Special report series No. 44, New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research, India.

Publisher | Google Scholor - BIS. (2012). Indian standard drinking water-specification. 2nd revision. New Delhi. Bureau of Indian Standards, India.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2001). Endemic fluorosis in southern Rajasthan (India). Fluoride, 34(1):61-70.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa DK. (2001). Endemic fluorosis in Rajasthan. Indian J Environ Health, 43(4):177-189.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2018). A brief and critical review of endemic hydro fluorosis in Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 51(1):13-33.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa D. (2019). Genu-valgum (knock-knee) syndrome in fluorosis- endemic Rajasthan and its current status in India. Fluoride, 52(2):161-168.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2022). The diagnosis and prevention of fluorosis in humans. J Biomed Res Environ Sci, 3(3):264-267.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (1999). Some observations on endemic fluorosis in domestic animals of southern Rajasthan (India). Vet Res Commun, 23(7):457-465.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2000). Fluoride toxicity in domestic animals in Southern Rajasthan. Pashudhan, 15(4):5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Swarup D, Dwivedi SK. (2002). Environmental pollution and effect of lead and fluoride on animal health. Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi, India.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2007). Fluoridated ground water and its toxic effects on domesticated animals residing in rural tribal areas of Rajasthan (India). Intl J Environ Stud, 64(2):151-159.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2008). Dental fluorosis in domestic animals. Curr Sci, 95(12):1674-1675.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2010). Osteo-dental fluorosis in horses and donkeys of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 43(1):5-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2010). Fluorosis in dromedary camels of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 43(3):194-199.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2012). Status of fluorosis in animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci, India Sect B: Biol Sci, 82(3):331-339.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Mishra GV, Sheikh Z, Bhardwaj B, Mali P, (2011). Toxic effects of fluoride in domestic animals. Adv Pharmacol Toxicol, 12(2):29-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Modasiya V, Bahura CK, Sheikh Z. (2012). Toxicity of fluoride in cattle of the Indian Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 45 (4):371-376.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2013). Fluorotoxicosis in diverse species of domestic animals inhabiting areas with high fluoride in drinking waters of Rajasthan, India. Proc Natl Acad Sci, India Sect B: Biol Sci, 83(3):317-321.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2013). Fluoride toxicosis in immature herbivorous domestic animals living in low fluoride water endemic areas of Rajasthan, India: an observational survey. Fluoride, 46(1):19-24.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Mishra GV. (2013). Fluoride toxicosis in bovines and flocks of desert environment. Intl J Pharmacol Biol Sci, 7(3):35-40.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2014). Bovine calves as ideal bio-indicators for fluoridated drinking water and endemic osteo-dental fluorosis. Environ Monit Assess, 186(7):4493-4498.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2021). Chronic fluoride exposure and its diverse adverse health effects in bovine calves in India: an epitomised review. Glob J Biol Agric Health Sci, 10(3):1-6. Or 10:107.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2022). A brief and critical review of chronic fluoride poisoning (fluorosis) in domesticated water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in India: focus on its impact on rural economy. J Biomed Res Environ Sci, 3(1):96-104.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2022). A brief review of chronic fluoride toxicosis in the small ruminants, sheep and goats in India: focus on its adverse economic consequences. Fluoride, 55(4): 296-310.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Endemic hydrofluorosis in cattle (Bos taurus) in India: an epitomised review. Int J Vet Sci Technol, 8(1):001-007.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Chronic fluoride poisoning in domestic equines, horses (Equus caballus) and donkeys (Equus asinus). J Biomed Res, 4(1):29-32.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). A brief review of endemic fluorosis in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) and focus on their fluoride susceptibility. Austin J Vet Sci & Anim Husb, 10(1): 1-6,1117.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2022). How can fluorosis in animals be diagnosed and prevented? Austin J Vet Sci & Anim Husb, 9(3):1-5,1096.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Anon. (1990). The improvement of tropical and subtropical rangelands, Washington, DC, USA. National Academy Press.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Susheela AK, Das TK. (1988). Chronic fluoride toxicity. A scanning electron microscopic study of duodenal mucosa. Clin Toxicol, 26:467-470.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2018). A brief and critical review on hydro fluorosis in diverse species of domestic animals in India. Environ Geochem Health, 40(1):99-114.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa D, Choubisa A. (2023). Fluoride contamination of groundwater and its threat to health of villagers and their domestic animals and agriculture crops in rural Rajasthan, India. Environ Geochem Health, 45:607-628.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2022). Status of chronic fluoride exposure and its adverse health consequences in the tribal people of the scheduled area of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 55(1):8-30.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Sompura K, Choubisa DK, Pandya H, Bhatt SK, et al. (1995). Fluoride content in domestic water sources of Dungarpur district of Rajasthan. Indian J Environ Health,37(3):154-160.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Sompura K, Choubisa DK, Sharma OP. (1996). Fluoride in drinking water sources of Udaipur district of Rajasthan. Indian J Environ Health, 38(4):286-291.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (1996). An epidemiological study on endemic fluorosis in tribal areas of southern Rajasthan. A technical report. The Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, New Delhi, 1-84.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (1997). Fluoride distribution and fluorosis in some villages of Banswara district of Rajasthan. Indian J Environ Health, 39(4):281-288.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2018). Fluoride distribution in drinking groundwater in Rajasthan, India. Curr Sci, 114(9):1851-1857.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Is drinking groundwater in India safe for domestic animals with respect to fluoride? Arch Animal Husb & Dairy Sci, 2(4):1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Is drinking groundwater in India safe for human health in terms of fluoride? J Biomed Res, 4(1):64-71.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Can people get fluorosis from drinking water from fresh water sources? Fluoride test of water mandatory before its supply. SciBase Epidemiol Publ Health, (In press).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bhargava D, Bhardwaj N. (2009). Study fluoride contribution through water and food to human population in fluorosis endemic villages of north-eastern Rajasthan. African J Basic Appl Sci, 1(3-4):55-58.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Pandya H, Choubisa DK, Sharma OP, Bhatt SK, (1996). Osteo-dental fluorosis in bovines of tribal region in Dungarpur (Rajasthan). J Environ Biol, 17(2): 85-92.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (1999). Chronic fluoride intoxication (fluorosis) in tribes and their domestic animals. Intl J Environ Stud, 56(5):703-716.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Mali P. (2009). Fluoride toxicity in domestic animals. In: Dadhich L, Sultana F, editors. Proceedings of the National Conference on Environmental Health Hazards.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2012). Study of natural fluoride toxicity in domestic animals inhabiting arid and sub-humid ecosystems of Rajasthan. A technical report. University Grants Commission, New Delhi, India,1-29.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). A brief and critical review of endemic fluorosis in domestic animals of scheduled area of Rajasthan, India: focus on its impact on tribal economy. Clin Res Anim Sci, 3(1):1-11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Is it safe for domesticated animals to drink fresh water in the context of fluoride poisoning? Clin Res Anim Sci, 3(2):1-5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gautam R, Bhardwaj N. (2009). Fluoride accumulation in milk samples of domestic animals of Newa tehsil in Nagaur district (Rajasthan). The Ecoscane, 3(3&4):325-326.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gupta P, Gupta N, Meena K, Moon NJ, Kumar P, (2015). Concentration of fluoride in cow’s and buffalo’s milk in relation to varying levels of fluoride concentration in drinking water of Mathura city in India - A pilot study. J Clinic Diagnos Res, 9(5):5-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pradhan BC, Baral M, Prasad S, Pradhan D. (2016). Assessment of fluoride in milk samples of animals of around Nalco Angul Odisha, India. Intl J Innov Pharmacut Sci Res, 4(1):29-40.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Raina S, Dua K, Singh S, Chhabra S. (2020). Urine and milk of dairy animals as an indicator of hydrofluorosis. J Anim Res, 10(1):91-93.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Asembo EO, Oliech GO, Wambu EW, Waddams KE, Ayiekod PO. (2021). Dental fluorosis in ruminants and fluoride concentrations in animal feeds, faeces, and cattle milk in Nakuru county, Kenya. Fluoride, 54(2):141-155.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Susheela AK. (2007). A treatis on fluorosis. 3rd ed. Delhi. Fluorosis and Rural Developmental Foundation, India, 15-16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2015). Industrial fluorosis in domestic goats (Capra hircus), Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 48(2): 105-115.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa D. (2015). Neighborhood fluorosis in people residing in the vicinity of superphosphate fertilizer plants near Udaipur city of Rajasthan (India). Environ Monit Assess, 187(8):497.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa D. (2016). Status of industrial fluoride pollution and its diverse adverse health effects in man and domestic animals in India. Environ Sci Pollut Res, 23(8): 7244-7254.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Industrial fluoride emissions are dangerous to animal health, but most ranchers are unaware of it. Austin Environ Sci, 8(1):1-4,1089.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). A brief review of industrial fluorosis in domesticated bovines in India: focus on its socio-economic impacts on livestock farmers. J Biomed Res, 4(1):8-15.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sompura K. (1997). Study of prevalence and severity of chronic fluoride intoxication in relation to certain determinants of the fluorosis. Ph. D. Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Verma R. (1996). Skeletal fluorosis in bone injury case. J Environ Biol, 17(1):17-20.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (1996). Radiological skeletal changes due to chronic fluoride intoxication in Udaipur district (Rajasthan). Poll Res, 15(3):227-229.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2012). Toxic effects of fluoride on bones. Adv Pharmacol Toxicol, 13(1):9-13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2022). Radiological findings more important and reliable in the diagnosis of skeletal fluorosis. Austin Med Sci, 7(2):1-4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - T Chakma, SB Singh, S Godbole, RS Tiwari. (1997). Endemic fluorosis with genu valgum syndrome in a village of district Mandla, Madhya Pradesh. Indian Paediatrics, 34:234-235.

Publisher | Google Scholor - T Chakma, PV Rao, SB Singh, RS Tiwari. (2000). Endemic genu valgum and other bone deformities in two villages of Madla district in central India. Fluoride, 33(4):187-195.

Publisher | Google Scholor - SV Gitte, R Sabat, K Kambl. (2015). Epidemiological survey of fluorosis in a village of Bastar division of Chhattisgarh state, India. Intl J Med Pub Health, 5(3):232-235.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sharma JD, Sohu D, Jain P. (2009). Prevalence of neurological manifestations in a human population exposed to fluoride in drinking water. Fluoride, 42(2):127-132.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh VP, Chauhan DS, Tripathi S, Kumar S, Gaur V, Tiwari M, et al. (2013). A correlation between serum vitamin, acetylcholinesterase activity and IQ in children with excessive endemic fluoride exposure in Rajasthan, India. Intl Res J Med Sci, 1(3):12-16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Spittle B. (2016). Dental fluorosis as a marker for fluoride-induced cognitive impairment, (Editorial). Fluoride, 49(1):3-4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Guo Z, He Y, Zhua Q. (2008). Research on the neurobehavioral function of workers occupationally exposed to fluoride. Industrial Health and Occupational Diseases; 2001;27(6):346-8. (in Chinese). Translated by Julian Brooke and published with the concurrence. Industrial Health and Occupational Diseases in Fluoride, 41(2):152-155.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh VP, Chauhan DS, Tripathi S. (2014). Acetylcholinesterase activity in fluorosis adversely affects mental well-being: an experimental study in rural Rajasthan. European Acad Res, 2(4):5857-5869.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Sompura K, Choubisa D. (2007). Fluorosis in subjects belonging to different ethnic groups of Rajasthan. J Commun Dis, 39(3):171-177.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. (2009). Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to nutritional status, living habits and occupation in rural areas of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 42(3):210-215.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. (2010). Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to age and sex in tribal districts of Rajasthan, India. J Environ Sci Engg, 52(3):199-204.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2010). Natural amelioration of fluoride toxicity (fluorosis) in goats and sheep. Curr Sci, 99(10):1331-1332.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. (2011). Reversibility of natural dental fluorosis. Intl J Pharmacol Biol Sci, 5(20):89-93.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Mishra GV, Sheikh Z, Bhardwaj B, Mali P, Jaroli VJ. (2011). Food, fluoride, and fluorosis in domestic ruminants in the Dungarpur district of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 44(2):70-76.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2012). Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to chemical constituents of drinking waters. J Environ Sci Engg, 54(1):153-158.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2013). Why desert camels are least afflicted with osteo-dental fluorosis? Curr Sci, 105(12):1671-1672.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa A. (2021). A brief review of ideal bio-indicators, bio-markers and determinants of endemic of fluoride and fluorosis. J Biomed Res Environ Sci, 2(10):920-925.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pramanik S, Saha D. (2017). The genetic influence in fluorosis. Environm Toxicol Pharmacol, 56:157-162.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Sompura K, Bhatt SK, Choubisa DK, Pandya H, Joshi SC, et al. (1996). Prevalence of fluorosis in some villages of Dungarpur district of Rajasthan. Indian J Environ Health, 38(2):119-126.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Sompura K. (1996). Dental fluorosis in tribal villages of Dungarpur district (Rajasthan). Poll Res, 15(1):45-47.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL, Choubisa DK, Joshi SC, Choubisa L. (1997). Fluorosis in some tribal villages of Dungarpur district of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 30(4):223-228.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (1998). Fluorosis in some tribal villages of Udaipur district (Rajasthan). J Environ Biol, 19(4):341-352.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sompura K, Choubisa SL. (1999). Some observations on endemic fluorosis in the villages of Sagawara Panchayat Samiti of Dungarpur district, Rajasthan. In: Proceedings of National Seminar on Fluoride, Fluorosis and Defluoridation Techniques. MLS University, Udaipur, 25(27):66-69.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2012). Fluoride in drinking water and its toxicosis in tribals, Rajasthan, India. Proc Natl Acad Sci, India Sect B: Biol Sci, 82(2):325-330.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Choubisa SL. (2023). Nalgonda technique is an ideal technique for defluoridation of water: its use can prevent and control hydrofluorosis in humans in India. Acad J Hydrol & Water Res, 1(1):15-21.

Publisher | Google Scholor