Research Article

Antenatal Care Drop Out and Associated Factors Among Those Gave Birth Women in Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia: Institutional-Based Cross-Sectional Study 2023

1Departments of Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, Mattu University, Mattu, Ethiopia.

2Departments of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Dagne Deresa Dinagde, Departments of Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, Mattu University, Mattu, Ethiopia.

Citation: Dagne D. Dinagde, Kassahun F. Tesema, Gemeda W. Kitil, Wolde F. (2024). Antenatal Care Drop Out and Associated Factors Among Those Gave Birth Women in Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia: Institutional-Based Cross-Sectional Study 2023, Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology Research, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(1):1-15. DOI: 10.59657/2992-9725.brs.24.008

Copyright: © 2024 Dagne Deresa Dinagde, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: January 08, 2024 | Accepted: February 29, 2024 | Published: March 08, 2024

Abstract

Background: To gain the life-saving and health-promoting promises of antenatal care, pregnant women need to have at least eight contacts with skilled healthcare providers, yet coverage in Sub-Saharan African countries, including Ethiopia, is only 58%. Hence, identifying risk factors for antenatal dropout would have reasonable implications for increasing antenatal utilization.

Objective: To assess the magnitude of antenatal care drop out and associated factors among those who gave birth in Arba Minch town, southern Ethiopia, in 2023.

Materials and Methods: An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 416 mothers who were enrolled from December 1, 2022, to January 30, 2023. The total sample size was allocated proportionately to the number of women who delivered at each public health facility. Thus, systematic sampling was applied. Kobo Toolbox was used for data collection and cleaning, which was then analyzed using SPSS Version 26. Statistical significance was determined at a p-value of Value of less than 0.05.

Results: In this study, the magnitude of antenatal care dropout was 59.1% (95% CI:54.7–62). The associated factors of antenatal care dropout were absence of pregnancy danger signs (AOR=4.1, 95CI:1.87, 8.82), absence of chronic disease (AOR=3.55, 95%CI:1.16, 10.87), poor satisfaction of antenatal care (AOR=3.46, 95CI: 1.84, 6.53), lack of bad obstetric history (AOR=3.90, 95CI: 1.94,7.83), antenatal contact at health center (AOR=5.1, 95CI: 2.28,11.21), poor knowledge about antenatal care (AOR=2.26, 95%CI: 1.15,4.44), and food insecurity (AOR=3.98, 95%CI: 1.96, 8.1),women’s low decision making power (AOR=3.9, 95CI: 1.2, 7.63), Domestic violence victims (AOR=2.0, 95% CI: 1.1, 3.71), negative perception of partner support (AOR=2.0, 95CI: 1.04,3.78),primiparous (AOR=2.9, 95CI: 1.14, 7.49) and consultation to traditional birth attendants (AOR=2.0, 95% CI: 2.13-3.80).

Conclusion: Dropout from antenatal follow-up is high in this study area. Absence of pregnancy danger signs, lack of chronic disease, client’s satisfaction, lack of bad obstetric history, antenatal contact at a health center, poor knowledge, food insecurity, women’s low decision-making power, negative perception of partner support, consultation with traditional birth attendants, and primiparity are key factors. Therefore, it's crucial to provide more information during antenatal contacts in order to lower the rate at which women drop out of antenatal care.

Keywords: antenatal care dropout; arba minch town; southern Ethiopia

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) is a maternal healthcare service provided by coordinated health care professionals to pregnant women in order to support and maintain their optimal health during pregnancy, delivery, and puerperium, as well as to have and raise a healthy baby. It also provides an opportunity for nutrition, birth preparation, delivery care, and post-partum contraceptive education [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended the four-visit ANC model since 2002 which recommend at least of four visits, but an updated version with eight ANC contacts was released in 2016 which call for ANC contacts before 12 weeks of gestation. The word “visit” in the previous model has now changed to “contact” to indicate an active interaction between a pregnant woman and a health-care provider [1] and the new model is implementing since Ethiopia adopted the new recommendation and incorporated in management protocol for hospitals in 2021 [2]. Women who do not attend each suggested contacts are considered to have dropped out of prenatal care [3]. Particularly in low-resource settings, women who receive skilled care during pregnancy often "drop out" during a critical period (pregnancy) of care and end up delivering at home or in the community without a certified, properly trained health professional, putting themselves and their newborns at risk [4]. Many maternal and prenatal deaths occur in women who have received inadequate and no utilization of ANC [5]. In Africa the coverage of antennal care was only 58% [6] with west and central Africa the lowest coverage of the services (53%) [7]. According to EDHS 2019 the percentage of women received at least one ANC visits by skilled profession were 74% and those received four or more 43% [8].

Before the introduction of antenatal care by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the 2000s, maternal mortality rates were at historically high levels around the world. In the 1990s, there were 400 maternal deaths worldwide for per 100,000 live births, which today decreased to 223 deaths per 100,000 live births [9, 10]. It decreases maternal mortality by 34% over two decades. However, still a woman is dying globally every two minutes from almost all preventable causes or other hand about 800 mothers dying in a day [11]. To combat this, WHO and other stakeholders are working to reduce maternal and child mortality through various intervention programs and strategies, like through end up preventable deaths, ensure health and well-being and expand enabling environments [12] and SDG planned to decrease maternal mortality below 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030 [13]. A different cross section study conducted across a world revealed that sociocultural and economic barriers, poor access to health services, and long distance from health facilities care services, lack of knowledge, lack of professional advice, poor wealth index and not developing a danger sign were factors associated with ANC drop out [14-16]. However, in this study variables such as type of institution, perceived quality of care, availability of Traditional Birth Attendant, level of respectful and non-abuse care, partner involvement, food insecurity and pregnancy related bad habits were additionally included in this study. Even though some studies have been conducted on the factors contributing to antenatal care utilization dropout in Ethiopia, following introduction of new recommendation of ANC model there is a little information and certainly undiscovered factors will be revealed with this study. Therefore, the objective of this study is to assess the magnitude ANC dropout and the factors related to ANC dropout contacts during pregnancy in Arba Minch town.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Period

The study was conducted in public health facilities in Arba Minch town. The town is located 505 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 275 km away from Hawassa, the commercial and administrative center of the southern region. According to the 2020 population projection, Arba Minch town has a total population of 108,956, with 55,568 females and 53,388 males. The town has two public hospitals, one private hospital and two health centers. All of the health facilities are providing perinatal care. There are 15 nurses and 30 midwives providing antenatal care in those health facilities. The public health institutions in the town are expected to serve more than half a million people in the town and nearby districts [17]. Data was gathered between December 1, 2022 and January 30, 2023.

Study Design

A facility-based cross-section study was employed.

Study Population

Mothers those gave birth and booked for ANC visits in public health facilities of Arba Minch town and are available during the data collection period.

Eligibility Criteria

All mothers who gave birth at Arba Minch town health facilities and who are willing to give information were included but those mothers critically ill on day of data collection and referred from other facilities outside Arba Minch were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination

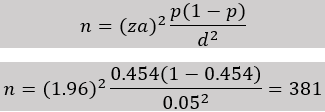

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula:  , considering the following assumptions: prevalence of ANC service utilization dropout was taken from study conducted in Debra Berhan town ( 45.4 %) [18], with confidence interval of 95% and, 5 % margin of error.

, considering the following assumptions: prevalence of ANC service utilization dropout was taken from study conducted in Debra Berhan town ( 45.4 %) [18], with confidence interval of 95% and, 5 % margin of error.

The sample size for the second objectives is generated by combining significant factors from three prior identical and related studies with a 95% confidence interval, 5% alpha, and 80% power.

Sampling Technique and Procedure

In Arba Minch town, there are two public hospitals and two public health centers, which provide curative and preventive services for the community. This study considers all public health centers and hospitals in the town. Mothers who gave birth in these health care facilities were then enrolled. The sample size for two health facilities was determined according to the proportionate probability technique. Thus, the total participants were identified from the delivery registration book of the previous year for the same months (i.e., December to January) from all four institutions. According to the 2021 report of each health facility's annual skilled birth attendant report, at similar times in the past two months, 496 women delivered in Arba Minch general hospital, 204 mothers gave birth in Dilfana primary hospital, 160 women delivered in Secha health center, and 100 women had given childbirth in Woze health center were used as sampling frame. Then, systematic random sampling was used to reach the respondents. Thus, the first respondent was selected by the lottery method among the 1st kth interval, while the remaining participants of the study were selected by every ‘k’th (i.e., every second) value for all institutions until the total sample size fulfilled (i.e.,419) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: schematic diagram shows proportional allocation of sample size of each health institution of Arba Minch town.

Data Collection Tool and Procedure

Questionnaire used an interviewer-administered semi-structured questionnaire was adapted from relevant literature [14, 19-23] with modifications and employed for data collection. The tool consists of four sections: socio-demographic, institutional, personal factors, and reproductive variables. The questionnaire was designed in English and Amharic language. Women who gave birth in public health facilities in Arba Minch town were enrolled by applying systematic sampling depending on case flow of the same two months of previous year, using it as a sampling frame. Then Four nurses and three midwives were recruited for data collection based on their past experience and fluency in the local language, and they were supervised by two MSc holder midwives.

Data Quality Management

Following an extensive review of relevant literature and similar studies, a data collection tool was developed to ensure the quality of the data. Properly designed data collection instruments were provided after two days of training for data collectors and supervisors. Pre-testing of the questionnaire was carried out two months before the commencement of the data collection among 20 mothers who gave birth in Shalle health center and all the necessary corrections were made based on the pretest result to avoid any confusion and for better completion of the questions. Every day, the collected data will be reviewed and cross-checked for completeness and relevance. Checking for double data entry, consistency, missing values, and outliers will be done by the supervisors and principal investigator, and comments and measures were undertaken throughout the data collection period.

Data Analysis and Entry

The data was coded, collected, cleaned, and entered by Kobo Toolbox and exported to statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 26 for analysis. Inconsistencies and missing values were checked by running frequencies and other data explorations. Descriptive statistics like frequency distributions mean and standard deviation were computed. Bivariate analysis was done primarily to check which independent variables had an association with that of the dependent variable. Independent variables with marginal associations (P lessthan 0.25) in the bivariate analysis, which are biologically plausible and showed significant association in the previous studies was entered in to a multivariate logistic regression analysis in order to detect association with antenatal dropout. The multicollinearity was checked among independent variables and Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to check the appropriateness of the model for analysis. Finally, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% CI was estimated to assess the strength of associations and statistical significance was declared at a p-value lessthan 0.05 and results will be presented using tables, figures, and texts.

Operational Definition and measurements

Antenatal care drop out-Women are regarded to have dropped out of prenatal care if they did not attend each suggested visit according to new WHO recommendation or on another hand it included those have delay registration of ANC or discontinue from the services [3].

Food insecurity: The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) developed by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) Program of the United States Agency for International Development will be used to assess household food security. It consists of 9 items and in this study, household food security status was divided into two categories: "food secure" when participants did not experience any food access conditions in the previous four weeks, and "food insecure" when they were unable to access sufficient food at all times to lead an active and healthy life [24].

Client satisfaction of antenatal care: The overall of client satisfaction was measured by scoring responses; a score ‘1’ was Yes and ‘0’ for No. A total score was computed and a client who had scores above the mean is labeled as having good satisfaction towards antenatal care; otherwise, client is categorized as poorly satisfied [25].

Knowledge of ANC: The overall level of antenatal care knowledge was evaluated by scoring responses that measure participants' knowledge based on the descriptions below; a score of 1 was assigned if the participant has knowledge and a score of 0 if they do not. A total score and a mean score were computed, with a score less than the mean indicating poor knowledge and a score equal to or higher than the mean indicating good knowledge [26].

Attitude towards ANC- is measured by using Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = disagree, and 4 = strongly disagree). Positive attitude was assigned for those scored by participants who respond above the mean of the attitude assessment questions and if below the mean they were categorized as having negative attitude [27].

Intimate partner violence- The 5 item Women's Abuse Screening Test (WAST) scale was used to assess intimate partner violence. WAST scores range from 1 to 16, with a score greater than 1 indicating the presence of violence [28].

Women’s decision-making power: This is one of the key indicators that measure the level of women’s involvement in household decision-making regarding consumption and expenditures, reproductive choices. It was labeled as had high decision-making power if mother involved in decision make independently or with others and assigned to have poor decision-making power if never involved in decision making [29].

Level of respect and non-abuse care - A woman was labeled as “disrespected and abused in the respective category” if she reported “Yes” to at least one of the questions during childbirth. If a mother was responded “NO’’ to six questions, she was considered “good level of respect [30].

Distance of facility- long distance if it takes more than 60 min to reach health facility and short distance if takes less than 30 min [20].

Types of institution: hospital, health center or health post to which they more prefer to go.

Partner support: Partner support was assessed using a modified 8-item Spousal Support Scale (SSS) is customized based on the local context. SSS scores range from 8 to 48, and reverse scoring was used (5=strongly agree to 1=strongly disagree). A score higher than the mean value indicates that the respondent has a positive perception of partner support [31].

Health insurance status: mothers those have or not insurance card for free charge health services [14]

Waiting-time: prolonged waiting hour to get services as if mother waits for >30 minutes and not if get services within 30 minutes [32].

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

Out of the 419 study participants, 416 were actually interviewed and provided accurate information, yielding a response rate of 99.3%, while three participants declined to participate in the study as they rushed to leave. The mean age of the women was 29.7 years (SD ± 6) with a minimum and maximum age of 18 and 42, respectively. The majority of the participants, two hundred seventy-six (52.9%), were Orthodox Christians. Most women, one hundred sixty-four (39.4%), can read and write. The majority of the women, two hundred four (49%), were housewives and about one hundred sixty-four (39.4%) can write and read. Three hundred sixty-four (83.2%) of the study participants have a monthly income of more than five thousand Ethiopian birr (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants at Arba Minch town (n=416); 2023.

| Variables | Response | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Age (in years) | <20> | 7 | 1.7 |

| 20-24 | 90 | 21.6 | |

| 25-29 | 103 | 24.8 | |

| 30-34 | 88 | 21.2 | |

| 35 and above | 128 | 30.8 | |

| Residence | Rural | 130 | 31.3 |

| Urban | 286 | 68.8 | |

| Maternal education | Unable to read and write | 99 | 23.8 |

| Able to read and write | 164 | 39.4 | |

| Primary | 91 | 21.9 | |

| Secondary school & above | 62 | 14.9 | |

| Maternal occupation | civil servant | 81 | 19.5 |

| Farming | 23 | 5.5 | |

| house wife | 204 | 49.0 | |

| Traders | 108 | 26.0 | |

| Husband education | Unable to read and write | 87 | 20.9 |

| Able to read and write | 175 | 42.1 | |

| Primary | 64 | 15.4 | |

| Secondary school & above | 90 | 21.6 | |

| Husband occupation | Farming | 151 | 36.3 |

| Traders | 96 | 23.1 | |

| civil servant | 168 | 40.4 | |

| Income | < 2500> | 13 | 3.1 |

| 2501-5000 ETB | 57 | 13.7 | |

| > 5000 | 346 | 83.2 |

Facility Related Factors

Two hundred five (73.3%) of the participant showed that they waited longer than 30 minutes to get ANC service. Thirty-seven (8.9%) of the respondents said that they travel more than 1 hour to get ANC service, and one hundred twenty-one (29.1%) of the respondents traveled to the health center on foot, and twenty-nine (9%) were transported by mule or horse. The majority of women (81.5%) those travelled by car or motor pay more than 20 Ethiopian Birr to arrive at a medical facility and receive ANC care. Majority (82.2) have previous history of ANC visits. Only forty-six (11.1%) of the respondents said that they were not counseled about ANC services during a previous pregnancy by health professionals and only fourteen (3%) of mothers reported that they had experienced good level of respect and non-abuse care (Table 2).

Table 2: facilities related factors on ANC among study participants in Arba Minch town, south Ethiopia; 2023(n=416).

| Variables | Response | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Distance in time | ≤30 minutes | 42 | 10.1 |

| 30-60 minutes | 337 | 81.0 | |

| > 1 hour | 37 | 8.9 | |

| Mode of transportation | Horse/on foot | 150 | 36.1 |

| By car | 266 | 63.9 | |

| Cost of transport | ≤ 20 ETB | 77 | 18.5 |

| > 20 ETB | 339 | 81.5 | |

| Advice about ANC | Yes | 370 | 88.9 |

| No | 46 | 11.1 | |

| Waiting time | ≤ 30 minutes | 111 | 26.7 |

| > 30 minutes | 305 | 73.3 | |

| History of ANC | Yes | 342 | 82.2 |

| No | 74 | 17.8 | |

| Level of respect | Good level of respect | 14 | 3.4 |

| Poor level respect | 402 | 96.6 |

Reproductive and Personal Factors

Most mothers, three hundred fifty-eight (84%), of mothers were multiparous and had more than two children, and three hundred six (73.6%) of mothers said the pregnancy was wanted. Most, two hundred seventy (81%), mothers gave birth through SVD previously, and one hundred twenty-nine (31%) have a history of bad obstetrics like stillbirth, congenital anomalies, abortion, and neonatal death. Half (47%) of mothers have responded that there were traditional birth attendants (TBAs) to whom they talked about their pregnancy sometimes in their villages. Forty-nine (21.9%) of mothers have a history of pregnancy danger signs and some complications. And about thirty-six (8.7%) had chronic illnesses like Diabetes Mellitus, asthma, hypertension. Etc. The majority, three hundred forty-two (82.2%), have previous history of antenatal care. The overall two hundred thirty-eight (57.2%) study participants had high decision-making autonomy for maternal and their neonates’ health care service utilization (Table 3).

Table 3: Reproductive and Personal Factors on ANC among study participants in Arba Minch town, south Ethiopia; 2023 (n=416).

| Variables | Options | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Insurance card | Yes | 265 | 63.7 |

| No | 151 | 36.3 | |

| Parity | Primipara | 67 | 16.1 |

| Multipara | 349 | 83.9 | |

| wanted pregnancy | Yes | 306 | 73.6 |

| No | 110 | 26.4 | |

| Had history of ANC | Yes | 342 | 82.2 |

| No | 74 | 17.8 | |

| Mode of delivery | SVD | 270 | 81 |

| C/S | 63 | 19 | |

| Media exposure | Yes | 321 | 77.2 |

| No | 95 | 22.8 | |

| consultation to TBAs | Yes | 196 | 47.1 |

| No | 220 | 52.9 | |

| Bad obstetric history | Yes | 138 | 33.2 |

| Variables | Options | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| No | 278 | 76.8 | |

| Pregnancy danger Sig | Yes | 91 | 21.9 |

| No | 325 | 78.1 | |

| Chronic illness | Yes | 36 | 8.7 |

| No | 380 | 91.3 | |

| Knowledge of ANC | Good knowledge | 212 | 51 |

| Poor knowledge | 204 | 49 | |

| Patients’ attitude | Positive Attitude | 241 | 57.9 |

| Negative Attitude | 175 | 42.1 | |

| Partner support | Good | 231 | 55.5 |

| Poor | 185 | 44.5 | |

| IPV | No IPV | 173 | 41.6 |

| IPV | 243 | 58.4 | |

| Food security | food insecure | 307 | 73.8 |

| food secure | 109 | 26.2 | |

| Client’s satisfaction | Satisfied | 226 | 54.3 |

| Unsatisfied | 190 | 45.7 | |

| Women’s autonomy | Low Decision-making power | 178 | 42.8 |

| High Decision-making power | 238 | 57.2 |

Personal Habit

Fifty-eight (14%) of respondents were known to have bad habits such as drinking and chewing, with twenty-six (44.8%) using it occasionally and thirty-two (55.2%) using it weekly.

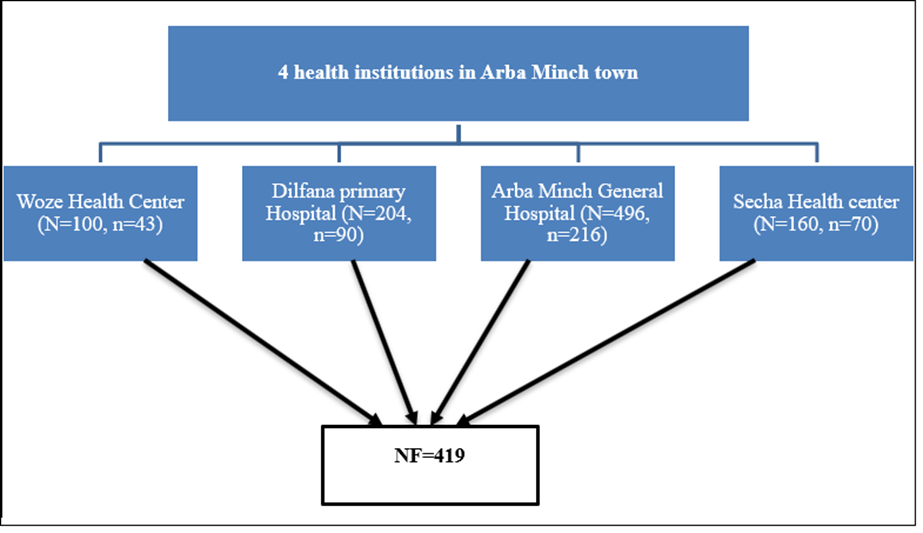

Magnitude of ANC dropout

From a total of 416 women booking ANC follow up, the magnitude of ANC dropout was two hundred forty-six (59.1%) with a 95%CI (54.7, 62), or on the other hand, one hundred seventy-three (70.3%) of the participants were claimed to delay registration and seventy-three (29.7%) of the participants were discontinue from eight contact ANC service: as assessed according to the modified WHO recommendation (Figure 2).

Figure 2:missed contact per ANC schedule, WHO 2016, among study participants dropped out from ANC services in Arba Minch town, south Ethiopia; 2023(n=246).

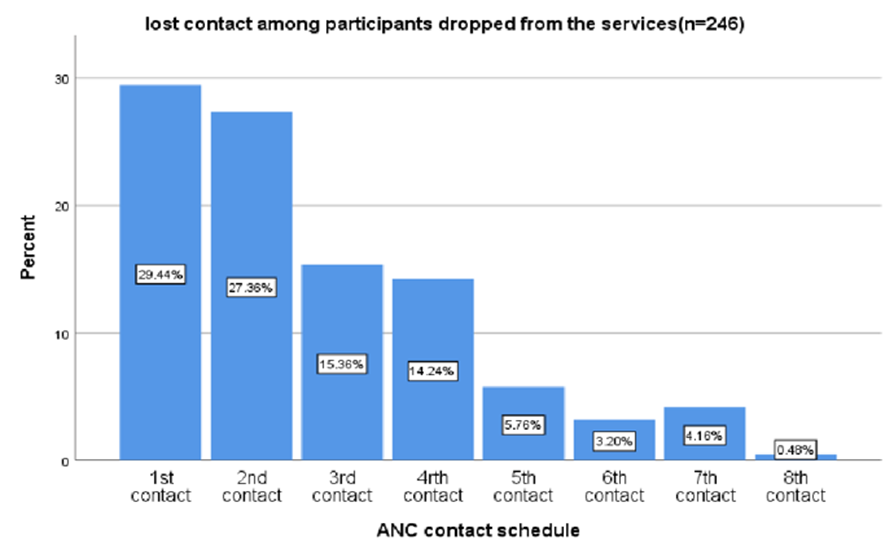

When asked why they dropped out of antenatal care, twenty-one (8.5%) of respondents were felt healthy, seven (2.8%) were busy, twenty-two (8.9%) were lived too far away and twenty-three (9.3%) were perceived the service was not attractive (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The reason of ANC drops out among study participants in Arba Minch town, south Ethiopia; 2023(n=246).

Factors associated with ANC dropout

Assumptions for logistic regression like large enough sample (minimum of 10 observations for each independent variables), residuals (>3), normal distribution (Shapiro wilk’s test (p greaterthan 0.05) and visual inspection of histogram, normal Q-Q plots and box plots) and no multicollinearity (with <0>0.1 & VIF lessthan 10 sig=0.418). In the bivariate binary logistic regression those variable with p lessthan 0.25 were candidates for multiple logistic regression and statistical significance was declared at a p-value lessthan 0.05 as below. Thus, age, maternal education, maternal occupation, marital status, parity, religion, type of institution, mode of transport, husband education, husband occupation, distance, counsel on ANC, waiting time, having community insurance card, income, unwanted pregnancy, exposure to media, TBA, BOH, pregnancy danger signs, chronic illness, patients attitude towards ANC, partner support, IPV, level of respect, food insecurity, client’s satisfaction, women’s autonomy and knowledge about ANC were candidates for multivariate.

This study's multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that types of health facilities, the involvement of TBA in pregnancy care, parity, bad obstetric history, chronic illness, pregnancy danger signs, patients' knowledge, the client’s satisfaction, maternal household food status, partner support and women's autonomy all had a statistically significant association with the outcome variable, ANC dropout (table 4). The types of health facilities had a positive association with ANC dropout, with mothers attending their ANC services at a health center dropping out 5 times more than those attending services at a hospital (AOR=5.1, 95CI: 2.28,11.21). Those primiparous mothers were 3 times more likely to drop from ANC per schedule relative those never gave birth before (AOR=2.9, 95CI: 1.14, 7.49). Those mothers who have TBAs consultation in villages in pregnancy care were 2 times more likely to drop from ANC as compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI: 2.13-3.80). Furthermore, mothers who did not have a BOH were 4 times more likely to discontinue ANC contact as compared to those had BOH like still birth, congenital anomaly, neonatal death and recurrent abortion (AOR=3.90, 95CI: 1.94,7.83). Knowledgeable mothers were found to consume ANC services as compared to those has no good knowledge or those mothers has poor knowledge were 2 times more likely to drop out from ANC follow up as compared to its counterparts (AOR = 2.26, 95%CI: 1.15,4.44). Mothers who did not experience any danger signs during this pregnancy were 4 times more likely to drop out than those who did (AOR=4.1, 95CI: 1.87, 8.82). And mothers with chronic illnesses such as diabetes, asthma, or high blood pressure are less likely to drop the services (AOR = 3.55, 95%CI: 1.16, 10.87).

The client’s satisfaction towards ANC services has a significant impact on service utilization, with poor client’s satisfaction contributing to a fourfold dropout rate (AOR=3.46, 95CI: 1.84, 6.53). Those mothers who had been exposed to IPV were 2 times more likely to drop out of services than those who had not been exposed to IPV (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.1, 3.71). Mothers from food-insecure households were 4 times more likely to discontinue ANC than their counterparts (AOR = 3.98, 95%CI: 1.96, 8.1). Mothers with low decision-making power were 3.9 times more likely to discontinue ANC contacts according to schedules (AOR=3.9, 95CI: 1.2, 7.63). And those mothers do not positively support with their partner were 2 times more likely to dropout from antenatal care as compared to those have support from their partners (AOR=2.0, 95CI: 1.04,3.78) (Figure 3).

Table 4: multivariate logistic regression analysis result for variables associated with ANC dropout among pregnant mothers Gave birth at Arba Minch health facilities (N=416).

| Variables | ANC Dropout | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||||

| Health facility | H. center | 90(81.8) | 20(18.2) | 4.33(2.537,7.379) | 5.1(2.28,11.21) | .000* |

| Hospital | 156(51) | 150(49) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Parity | Primiparous | 54(80.6) | 13(20.4) | 3.4(1.55,5.9) | 2.91(1.14,7.49) | .026* |

| Multiparous | 192(55) | 157(45) | 1 | 1 | ||

| TBA available in villages | Yes | 143(73) | 53(27) | 3.07(2.03,4.63) | 2(1.1,3.81) | .033* |

| No | 103(46.8) | 117(53.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| BOH | Yes | 56(40.6) | 82(59.4) | 1 | 1 | .000* |

| No | 190(68.3) | 88(31.7) | 3.16(2.07,4.83) | 3.9(1.94,7.83) | ||

| Pregnancy danger signs | Yes | 27(29.7) | 64(71.1) | 1 | 1 | .000* |

| No | 219(67.4) | 106(32.6) | 4.89(2.92,8.14) | 4.1(1.87,8.82) | ||

| Chronic disease | Yes | 10(27.8) | 26 (72.2) | 1 | 1 | .027* |

| No | 236(62.1) | 144(37.9) | 4.26(1.99,9.09) | 3.55(1.16,10.87) | ||

| Partner support | Positive perception | 98(42.4) | 133(57.6) | 1 | 1 | .037* |

| Negative perception | 148(80) | 37(20) | 5.43(3.62,8.19) | 2.0(1.04,3.78) | ||

| Patient’s knowledge | Good Knowledge | 81(38.2) | 131(61.8) | 1 | 1 | .018* |

| Poor Knowledge | 165(80.9) | 39(19.1) | 6.84(4.19,10.52) | 2.26(1.15,4.44) | ||

| Food insecurity | food insecure | 221(72) | 86(28) | 8.63(5.18,14.40) | 3.98(1.96,8.1) | .026* |

| food secure | 25(22.9) | 84(77.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Client’s satisfaction | Satisfied | 91(40.3) | 135(59.7) | 1 | 1 | .000* |

| Unsatisfied | 155(81.6) | 35(18.4) | 6.57(4.18,10.34) | 3.46(1.84,6.53) | ||

| Women’s autonomy | Autonomous | 147(82.6) | 31(17.4) | 4.68(3.04,7.21) | 3.9(1.2,7.63) | .000* |

| Not autonomous | 99(41.6) | 139(58.4) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intimate part violence | No IPV | 89(45.7) | 94(54.3) | 1 | 1 | .006* |

| IPV | 157(68.7) | 76(31.3) | 0.15(.09.24) | 2.0(1.1,3.71) | ||

* = p lessthan (statistically significant), 1=Reference group.

Discussion

The current study revealed the magnitude of antenatal care dropout was 59.1%. This finding is in line with a study conducted in Northern Busia in 2015 (55.9%) [33], however this finding is higher than a study conducted in Dhanusha district of Nepal in 2016 which was (50.47%) [34], and a study conducted in Punjab, Pakistan in 2014 (32.9%) [35], Nigeria 2016(38.1%) [36], and a study conducted in Tanzania revealed similarly, about 33% of mothers drop out from antenatal care follow up [37]. This may be acceptable given that all of the research mentioned above provided data using focused ANC, which was easy to return back and had a low dropout rate.

This finding also higher than the study conducted in different parts of Ethiopia, like a study conducted at Dire Dawa town, Eastern Ethiopia in 2021 (37.4%) [20] and at Debra Berhan town, northeast Ethiopia in 2022 (45.4%) [18]. The more plausible explanation for this could be related to the current adoption of the 2016 WHO recommendation on ANC in Ethiopia, which calls for eight contacts.

Women’s knowledge of ANC is crucial in the utilization of ANC services during pregnancy. This finding revealed those mothers have poor knowledge (not well knowledgeable) about ANC were about 2-times more likely to dropout from ANC as compared to those has good knowledge about ANC. This study is in line with study conducted Pakistan [38], in Ghana [39], Somalia [40] and Gonder town, Ethiopia [41]. It is known that women who are knowledgeable about ANC services are more likely to comprehend and appreciate the services offered during ANC.

Poor satisfaction of ANC services was also statically significant with ANC drop out. Those mothers who have poor perception towards quality of antenatal care were 3.5 times more likely to drop from ANC follow up when compared to those have good perception. This is consistent with study conducted in northern Ethiopia [25] and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [42]. This might be explained by clients having problems reaching a health institution and not receiving service soon, which in turn might affect clients’ perception of quality care.

The odds of antenatal care drop out among those women with no bad obstetric history (BOH) were 4-times more likely as compared to those have bad obstetric history. This finding is supported by study conducted in Rwanda [43]. They may be afraid that the same thing would happen again, which could be the cause of bad outcome.

The use of adequate antenatal care services was substantially correlated with the development of danger signs during pregnancy. Women who did not experience a danger sign during their pregnancy were 4- times more likely to stop attending prenatal care appointments than those who did. This result is in line with studies conducted at Bahir Dar Zuria [19] and shashemane, south Ethiopia [44] which indicates that mothers were more likely to use the services when they were aware of pregnancy risk factors. They may have never missed an appointment because they were afraid of the consequences.

This finding also found that women who consult to traditional birth attendants in the villages were about 2-times risk to drop from recommended ANC contact as compared to those do not consult to them. This is supported by studies conducted in Northern Busia [33] and Angolella Tara, Ethiopia [45] also stated the effect of TBA on ANC services usage. As justified as mothers may consult the TBA when they feel discomfort about their pregnancy.

The completion of the ANC follow up was statistically and favorably related to having authority over medical decision-making. The odds of those mothers dropped from ANC follow up were 4 times among those mothers have low decision-making power as compared to its counterparts. This research is consistent with that from Pakistan [35] and northwest Ethiopia [21]. This may be because women with control over health care decisions may have greater mobility, less financial concerns, and the ability to travel independently to receive care. Additionally, there may be a relationship between autonomy and other factors including women's education and urban residence, both of which are related with an increased likelihood of using maternal health care.

Those women who had no chronic disease were more likely to forego ANC follow up per schedule. Those mothers who have no chronic illness were 3.5-times more likely to drop from antenatal care as compared to those have chronic illness. This finding was similar with study conducted at Pomerania, Poland [46]. This may be explained by the fact that frequent appointments and risks to have a higher incidence of complications.

It was found that food insecurity was a separate determinant in how often mothers sought medical attention. This study also consistently found that women from food-insecure households had higher, 4-times, likelihood of dropping from ANC follow up than women from food-secure homes. This Finding is supported by study conducted among the poorest Americans [47] and southern Ethiopia [48]. The fact that women in impoverished nations like Ethiopia spend more time on home responsibilities than on their health may help to explain this. Because food demand outweighs healthcare demand, women in homes experiencing food insecurity may decide against obtaining ANC.

Furthermore, the study observed that a higher odd of intimate partner violence was seen among those drops from ANC follow up per schedule. In contrast to women who had not experienced IPV, those who had experienced it were two times more likely to drop prenatal care. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in SSA [49], Rwanda [50], Benin [51] pointing that, Women who experienced IPV were less likely to utilize timely ANC compared to those who did not experience IPV. The possible justification could be due to the lack of social support from their partners/husbands to inform them on their timely utilization of ANC. Because of this, women who are less than 12 weeks pregnant may not modify their behavior for the better to attend ANC appointments on time.

This study also found that a higher odd of negative perception of partner support was seen among those drops from ANC follow up per schedule. Women who have negative perception of partner support were 2 times more likely to drop from antenatal follow up when compared to its counterparts. This finding was supported by studies conducted in Gulu district, Uganda [52] and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [53, 54]. A potential reason for the link could be that when male partners become more involved, their knowledge grows and they adopt a more favorable attitude toward maternal health services.

The odds of dropping from antenatal care were 3 times more likely among primiparous as compared to multiparous women. This is supported by study conducted in Uganda [55] but different with study conducted in Thatta, Pakistan [38], Rwanda [43] and Ethiopia [14]. This might be because women who are multiparous have used antenatal care before and are familiar with the warning signs of pregnancy.

Types of health institution at they were receiving ANC services have to be positively correlated with ANC dropout. Those mothers receiving their antenatal care at health center were 5 times more likely to forgo ANC as compared to those follow up their ANC at hospital. This may justify as more sophisticated services and counseling given at hospital level with better health professional.

Strength and Limitation of the Study

The size of the sample employed in this study supports the generalizability of the results to all women in the study area who are of reproductive age. Information in the survey is based on self-reports, so there may be socially desirable bias and recall bias. Thus, medical record card parallelly checked to minimize recall bias. Additionally, the whole literature review for the study was according to focused antenatal care, which reduced the comparability's accuracy.

Conclusion

This study showed that the study area had a high magnitude of pregnant women who dropped out of ANC. food security status, bad obstetric history, danger signs of pregnancy, chronic illness), intimate partner violence, ANC follow up at health center, consultation of TBAs, as well as low women’s decision-making power, negative perception partner support, poor client’s satisfaction, being primiparous and poor knowledge are factors which associated with ANC dropout. Therefore, it's important to provide more information during the antenatal contacts in order to lower the rate of women dropped from antenatal care.

Abbreviations

ANC-Antenatal care

EMDHS-Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey

EDHS-Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey

IPV-Intimate Partner Violence

MMR-Maternal Mortality Rate

SSA-Sub Sahara Africa

SDG-Sustainable Development Goals

TBAs-Traditional Birth Attendants

Declarations

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used in the current study is not available to the general public. Since not all participants gave their permission for us to publish the raw data, but they are still available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I would like to thank Arba Minch University, College of Medicine and Health Science, for giving me this opportunity to conduct research on such important issue. Then my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my advisors’ supervisors, data collectors and study participants for their incredible support & guidance for accomplishment of this research.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board of Arba Minch University, College of Medicine and Health Science with reference number of IRB/1328/2022. Informed consent was obtained from study participants and the study was conducted according to regulations and guidelines for researches involving human beings.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The writers declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Author Contributions

Mr. Dagne Deresa developed the draft proposal and performed the statistical analysis and result write-up under the supervision of Mr. Kassahun Fikadu, Mrs. Fitsum Wolde, and Mr. Gemeda Wakgari participated in manuscript preparation. All authors made a significant contribution to the conception and conceptualization of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Organization WH. (2016). World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals: World Health Organization.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Obstetrics Management Protocol for Hospitals:2021.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ornella Lincetto SM-A, Patricia Gomez, Stephen Munjanja. (2015). Antenatal Care. Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Farmer P. (2001). Infections and inequalities. University of California Press.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Health Organization. (2016). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tessema ZT, Teshale AB, Tesema GA, Tamirat KS. (2021). Determinants of completing recommended antenatal care utilization in sub-Saharan from 2006 to 2018: evidence from 36 countries using Demographic and Health Surveys. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 21(1):192.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Merdad L, Ali MM. (2018). Timing of maternal death: Levels, trends, and ecological correlates using sibling data from 34 sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS One. 13(1): e0189416.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Indicators K. (2019). Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Organization WHO. (2019). Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fund UNP. (2003). Maternal mortality update 2002 a focus on emergency obstetric care. United Nations Population Fund New York.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Health Organization. (2016). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience Geneva: WHO.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tsegaye S, Yibeltal K, Zelealem H, Worku W, Demissie M, et al. (2022). The unfinished agenda and inequality gaps in antenatal care coverage in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 22(1):82.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hák T, Janoušková S, Moldan B. (2016). Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecological indicators. 60: 565-573.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muluneh AG, Kassa GM, Alemayehu GA, Merid MW. (2020). High dropout rate from maternity continuum of care after antenatal care booking and its associated factors among reproductive age women in Ethiopia, Evidence from Demographic and Health Survey 2016. PLoS One. 15(6): e0234741.

Publisher | Google Scholor - CSA. (2016). Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Birmeta K, Dibaba Y, Woldeyohannes D. (2013). Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Holeta town, central Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research. 13(1):256.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tessema KF, Gebremeskel F, Getahun F, Chufamo N, Misker D. (2021). Individual and Obstetric Risk Factors of Preeclampsia among Singleton Pregnancy in Hospitals of Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Hypertension.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tadese M, Tessema SD, Aklilu D, Wake GE, Mulu GB. (2022). Dropout from a maternal and newborn continuum of care after antenatal care booking and its associated factors in Debre Berhan town, northeast Ethiopia. Front Med (Lausanne). 9:950901.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bekele YA, Tafere TE, Emiru AA, Netsere HB. (2020). Determinants of antenatal care dropout among mothers who gave birth in the last six months in BAHIR Dar ZURIA WOREDA community; mixed designs. BMC Health Services Research. 20(1):846.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Worku D, Teshome D, Tiruneh C, Teshome A, Berihun G, et al. (2021). Antenatal care dropout and associated factors among mothers delivering in public health facilities of Dire Dawa Town, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 21(1):623.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Anguach Shitie, Merga Dhressa, and Tenagework Dilnessa. (2020). Completion and Factors Associated with Maternity Continuum of Care among Mothers Who Gave Birth in the Last One Year in Enemay District, Northwest Ethiopia.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Berhanie E, Gebregziabher D, Berihu H, Gerezgiher A, Kidane G. (2019). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a case-control study. Reproductive Health. 16(1):22.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Henok A, Worku H, Getachew H, Workiye H. (2015). Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Antenatal Care Service among Married Women of Reproductive Age Group in Mizan Health Center, South West Ethiopia. Journal of Medicine, Physiology and Biophysics. 16.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. (2007). Household Food Insecurity Access Scale for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Washington DC 29pp.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fesseha G, Alemayehu M, Etana B, Haileslassie K, Zemene A. (2014). Perceived quality of antenatal care service by pregnant women in public and private health facilities in Northern Ethiopia. American Journal of Health Research. 2(4):146-151.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Afaya A, Azongo TB, Dzomeku VM, Afaya RA, Salia SM, et al. (2020). Women’s knowledge and its associated factors regarding optimum utilisation of antenatal care in rural Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Plos one. 15(7): e0234575.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Girmaye E, Mamo K, Ejara B, Wondimu F, Mossisa M. (2021). Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Skilled Assistance Seeking Maternal Healthcare Services and Associated Factors among Women in West Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Nursing Research and Practice.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rabin R, Jennings J, Campbell J, Bair-Merritt M (2009) Intimate partner violence screening tools. American Journal of Prev Med. 36: 439.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Asabu MD, Altaseb DK. (2021). The trends of women’s autonomy in health care decision making and associated factors in Ethiopia: evidence from 2005, 2011 and 2016 DHS data. BMC Women's Health. 21(1):371.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Asefa A, Bekele D. (2015). Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 12(1):33.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Scale CG, Guidubaldi J, Cleminshaw HK. (1989). Development and Validation of the. The Second Handbook on Parent Education: Contemporary Perspectives. 2:257.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tsegaye Lire, Yisalemush Asefa and Agete Tadewos Hirigo. (2021). Antenatal care service satisfaction and its associated factors among pregnant women in public health centres in Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 1-8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Francis WP. (2013). Assessment of Dropout Rate and Contributing Factors among Women Attending Antenatal Care in Samia Bugwe North Busia District: Health Facility Based Survey.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Devendra Raj Singh1 TJ. (2016). Exploring Factors Influencing Antenatal Care Visit Dropout at Government Health Facilities of Dhanusha District, Nepal.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Muhammad Ashraf Majrooh, Javaid Akram, Arif Siddiqui, Zahid Ali Memon. (2014). Coverage and quality of antenatal care provided at primary health care facilities in the ‘Punjab’ province of ‘Pakistan.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Joshua O. Akinyemi. (2016). Patterns and determinants of dropout from maternity care continuum in Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Diwakar Mohan, Amnesty E LeFevre, Asha George, Rose Mpembeni, Eva Bazant, et al. (2017). Analysis of dropout across the continuum of maternal health care in Tanzania: findings from a cross-sectional household survey.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Aziz Ali S, Aziz Ali S, Feroz A, Saleem S, Fatmai Z, et al. (2020). Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care among married women of reproductive age in the rural Thatta, Pakistan: findings from a community-based case-control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 20(1):355.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Afaya A, Azongo TB, Dzomeku VM, Afaya RA, Salia SM, et al. (2020). Women's knowledge and its associated factors regarding optimum utilisation of antenatal care in rural Ghana: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 15(7): e0234575.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mohamoud AM, Mohamed SM, Hussein AM, Omar MA, Ismail BM, et al. (2022). Knowledge Attitude and Practice towards Antenatal Care among Pregnant Women Attending for Antenatal Care in SOS Hospital at Hiliwa District, Benadir Region, Somalia. Health. 14(4):377-391.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Janakiraman B, Gebreyesus T, Yihunie M, Genet MG. (2021). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of antenatal exercises among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PloS one. 16(2): e0247533.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hailu GA, Weret ZS, Adasho ZA, Eshete BM. (2022). Quality of antenatal care and associated factors in public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, a cross-sectional study. Plos one. 17(6): e0269710.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Schmidt CN, Butrick E, Musange S, Mulindahabi N, Walker D. (2021). Towards stronger antenatal care: Understanding predictors of late presentation to antenatal services and implications for obstetric risk management in Rwanda. Plos one. 16(8): e0256415.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Terefe N, Nigussie A, Tadele A. (2020). Prevalence of obstetric danger signs during pregnancy and associated factors among mothers in Shashemene Rural District, South Ethiopia. Journal of Pregnancy.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Taye BT, Zerihun MS, Kitaw TM, Demisse TL, Worku SA, et al. (2022). Women’s traditional birth attendant utilization at birth and its associated factors in Angolella Tara, Ethiopia. Plos one. 17(11): e0277504.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kersten I, Lange AE, Haas JP, Fusch C, Lode H, et al. (2014). Chronic diseases in pregnant women: prevalence and birth outcomes based on the SNiP-study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 14(1):75.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. (2006). Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 21(1):71-77.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zeleke EA, AN TH. (2020). Food Insecurity Associated with Attendance to Antenatal Care Among Pregnant Women: Findings from a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Southern Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Health. 13:1415-1426.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Aboagye RG, Seidu A-A, Asare BY-A, Adu C, Ahinkorah BO. (2022). Intimate partner violence and timely antenatal care visits in sub-Saharan Africa. Archives of Public Health. 80(1):124.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rurangirwa AA, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. (2017). Intimate partner violence among pregnant women in Rwanda, its associated risk factors and relationship to ANC services attendance: a population-based study. BMJ open. 7(2): e013155.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Idriss-Wheeler D, Yaya S. (2021). Exploring antenatal care utilization and intimate partner violence in Benin - are lives at stake? BMC Public Health. 21(1):830.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tweheyo R, Konde-Lule J, Tumwesigye NM, Sekandi JN. (2010). Male partner attendance of skilled antenatal care in peri-urban Gulu district, Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 10(1):53.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mohammed BH, Johnston JM, Vackova D, Hassen SM, Yi H. (2019). The role of male partner in utilization of maternal health care services in Ethiopia: a community-based couple study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 19(1):28.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. (2015). Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 69(6):604-612.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kawungezi PC, AkiiBua D, Aleni C, Chitayi M, Niwaha A, et al. (2015). Attendance and utilization of antenatal care (ANC) services: multi-center study in upcountry areas of Uganda. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine. 5(3):132.

Publisher | Google Scholor