Research Article

Analytical Investigation of the Factors Affecting the Supplier-Induced Demand in Healthcare: A Case Study of CT Scanning Department

1Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Payame Noor University, Tehran, Iran.

2PhD Student in Economics, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

3Master's degree graduate, Allame Tabatabaei University, Tehran, Iran.

*Corresponding Author: Samira Motaghi, Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Payame Noor University, Tehran, Iran.

Citation: Motaghi S., Farhadi E., Rajabian H. (2023). Analytical Investigation of the Factors Affecting the Supplier-Induced Demand in Healthcare: A Case Study of CT Scanning Department. Clinical Case Reports and Studies, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(6):1-10. DOI: 10.59657/2837-2565.brs.23.087

Copyright: © 2023 Samira Motaghi, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: November 03, 2023 | Accepted: November 17, 2023 | Published: November 24, 2023

Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the factors affecting the supplier-induced demand in health care with the help of an analytical-survey approach and using a questionnaire tool, and to analyze the role of medical technology centers, such as centers equipped with a CT scanning department, in development of this type of demand. The statistical population of the present research consisted of the patients referring to this department, out of whom 80 people were selected as the research sample using the simple random sampling method. After checking the normality of the data distribution through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, three research hypotheses were developed, all of which were confirmed by analyzing them using the Pearson correlation parametric test. The results of the data analysis indicated that the low patient information, high physician information, and high costs of healthcare service provider institutions have a positive effect on the supplier-induced demand in healthcare (especially in the departments with therapeutic technologies such as CT scanning). In addition, according to the results, the variable of high costs of healthcare provider organizations plays a more significant role in development of supplier-induced demand for healthcare providers, compared to the other two variables.

JEL classification: I10, I11.

Keywords: induced demand; healthcare provider organizations; CT scanning

Introduction

The healthcare sector throughout the world is developing increasingly, an issue that has made the behavior of this sector very similar to an economic market. In this regard, healthcare service providers, such as physicians, and patients have accepted their role as service providers and service receivers (customers), respectively. Therefore, healthcare economists seek to identify the relationship between the healthcare supply and demand and evaluate the differences between them in the healthcare sector and other economic sectors.

In this regard, the important point is the relationship and mutual trust between the healthcare service providers and the patient (in addition to their economic relationship), which, due to the patient's incomplete information about his/her illness, makes him/her a debtor to the supplier, and due to his/her lack of access to information (incomplete information) and the patients' low literacy easily affects his/her demand function for healthcare resources (Calcott, 1999).

This issue takes place in both developed and developing countries due to the exclusiveness of physicians’ and other healthcare providers’ knowledge, as well as the price-inelasticity of patients' demand (Bridge and Jones, 2007). However, in developing countries, it occurs more frequently due to the growth of resources providing healthcare to patients and the more restricted promotion of technology compared to developed countries (Talati and Pappas, 2006), as in these countries (developing countries), due to the smaller number of providers, the existing providers are the only available options for patients, and in such a situation, development of induced demand, which imposes financial burden on patients or affiliated organizations, is not avoidable and brings about a lot of economic justification for providers (Carlsen and Grytten, 2000).

What stands out as the difference between the healthcare market and other markets is that the healthcare provider first evaluates patients’ problems and needs and then recognizes the type and amount of care needed for them; and this is the factor that intensifies the supplier-induced demand, and while leading the patient to absolute poverty (spending a percentage of his/her income needed in other sectors on his/her treatment), it is identified as the source of creating an inappropriate healthcare situation. This situation becomes increasingly worse when a significant portion of health costs in healthcare systems are paid out-of-pocket (OOP) by most people (De Jaegher and Jegers, 2000); because apart from the fact that wrong or irrelevant diagnosis makes the patient face more side effects and leads to waste of time, economic problems, and a lot of cost for him/her and his/her family, it causes additional costs for the government and reduces the efficiency of national resources (Bickerdyke et al., 2002). In this regard, the need to pay attention to the supplier-induced demand in healthcare and the factors affecting it, in all levels and departments of the healthcare system (including the CT scanning department), is of great importance and calls policymakers and researchers for discussing and examining this issue.

Practical background and theoretical expectations (Supplier-Induced Demand)

Sekimoto et al. (2015) studied the demand induced by applicants for chronic disease care in Japan, with the aim of investigating the existence of induced demand in the treatment of chronic diseases by analyzing the patients’ data. They hypothesize that clinic and hospital physicians in the highly competitive areas (high physician density) recommend seeking advice earlier than those in the lower competition areas (low physician density). Then, using multilevel stochastic models, they examine the patients’ data and analyze the administrative claims in order to estimate the effects of physician density on encounter frequency and medical costs. In the data analysis, the average duration of drug use was considered as a proxy for the physician’s encounter frequency. Their findings indicated that the patient encounter frequency is significantly correlated with the clinic physician density, but there is no close correlation with the hospital physician density. Also, the increased physician density significantly depends on the increased clinic and hospital medical costs. In general, the results of their study showed that there is an induced demand in Japan.

Panahi et al. (2015) studies the induction effect of the number of physicians and hospital beds on health expenditure in Iran in order to investigate the presence of physician-induced demand in Iran's provinces using the panel data of the provinces in the period of 2000-2009. The results of the research model estimation indicated that the change in the number of physicians has a significant positive impact on the amount of health expenditures in the provinces. Therefore, the presence of induced demand in the health sector, which is known as Roemer's law, was confirmed in the provinces. However, in terms of the density of hospital beds, it was concluded that there is no supplier-induced demand, and an inverse relationship between these two variables and health expenditures was observed.

Considering the patient as the factor affecting induced-demand is due to the fact that the patient accepts the physician's prescription and any treatment because of the specialized aspect of health services and his/her concern for the disease consequences, which is due to his/her lack of knowledge about his/her disease and physical conditions. Now, if this little information is combined with the insufficient knowledge and skill of the healthcare service provider, it will lead to unnecessary tests and drugs and induced contractions, the most important side effects of which include the loss of time, depression caused by treatment, and confusion for patients (Keyvanara et al., 2013).

Sabatini Dwyer and Liu (2013) studied the effect of consumer health information on the demand for health services in order to empirically examine whether health information consumers use non-medical information sources as a substitute or supplement for health services (i.e., visits to physicians and emergency rooms (ER)). A measure of patient trust in physicians as a proxy for potential nonconforming heterogeneity can help consumers seek information and use physician services. After modification, sample selection, and adverse non-compliance control, the results were in agreement with the literature that paying attention to the consumer health information increases the likelihood of physician visits as well as the average number of visits. However, consumers with less health information make more visits to physicians and ERs than better informed consumers, which indicates that information can improve market efficiency.

Keyvanara et al. (2013) investigated the challenges resulting from induced demand for healthcare services, with the aim of identifying the challenges of induced demand using the experts’ experiences in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Iran. Their methodology was qualitative, and semi-structured interview was used to collect the data. Based on the thematic analysis conducted by them, 41 sub-themes and 3 main themes were extracted, with each having some sub-themes. The three main themes included: the challenges of insurance organizations, health system challenges, and patient challenges. Their results presented the challenges caused by induced demand, the most obvious of which included those mentioned above, i.e., the challenges of insurance organizations, health system challenges, and patient challenges. These findings can help the policy makers of the health sector to design appropriate strategies to address the challenges by considering them.

Woo Lee (2012) made an attempt to study asymmetric information and the demand for private health insurance in Korea in order examine the relationship between self-assessed health status (predicted as health risk) and demand for private health insurance using the longitudinal study data. Contrary to theoretical predictions, their results indicated that buying insurance can improve health. Their research evidence showed that this phenomenon is likely to be due to the screening by the insurers in the private insurance market in Korea.

The data related to the practicing output were merged with the information about the non-practicing income from the tax forms of physicians and their spouses, the results of which indicated that in the municipalities with a high density, physicians’ non-operating income does not influence the number of advices per physician or the number of treatment items per advice. Overall, the results are interpreted as evidence against the induced demand hypothesis.

Grytten et al. (2010) studied the impact of income and supplier-induced demand based on the evidence from primary care physicians in Norway. In their study, they investigated the relationship between the physician non-operating income and the provision of basic services by them. They argue that in the presence of induction, physicians with unsatisfactory low incomes work in municipalities where competition for patients is high and compensate for patient shortages by creating requirements. This model is compatible with the institutional setting of the Norwegian primary care physician, while there is a fixed fee schedule. Their analyses were performed on a data set from all the primary care physicians in Norway, considering each item of treatment cost.

Abdoli and Varahrami (2010) investigated the role of asymmetric information in induced demand in medical services. In order to compare the induced demand between formally- and informally-employed physicians, they prepared 300 questionnaires that was completed by 300 physicians living in Tehran, out of which 70 people were excluded from the study due to the fact that they were both employed by the government and had their own clinic. The variables of the “time of each visit to the physician and “the average number of tests prescribed by the physician for each patient” were considered as dependent variables, and the variables of “gender”, patient’s age”, “type of degree”, “experience”, “physician’s preference of income over leisure”, and “providing special services on their behalf” were considered as explanatory variables. According to their research findings, although the average number of tests prescribed by the physician and the time of each visit to him/her are affected by the patient’s gender and age, the variables of preference of income over leisure, experience, and providing special services played an effective in increasing the number of prescribed tests and the time of each visit to the physician, especially in the case of informally-employed physicians. Moreover, the research findings indicated that the induced demand for the use of medical and therapeutic services by general physicians is more, and the patients are more motivated to use all kinds of health and treatment services from informally-employed general physicians, compared to formally-employed ones. Accordingly, the adoption of standards and laws to monitor the performance of physicians who have private clinics can significantly reduce the unnecessary treatment expenses spent by patients.

Research Methodology

As applied research in terms of purpose and a survey study in terms of nature, the current study was carried out using the questionnaire approach in the statistical year 2022. In addition, in order to more closely examine the third part of the questionnaire (i.e., high costs of medical centers), a number (N=15) of physicians, personnel, and owners of medical centers and professors of Tehran University of Medical Sciences were interviewed, who confirmed the final results of this section. The research statistical population (in the section of ordinary people) consisted of all people referring to the CT scanning department in Tehran city, with their number being 100 people. The statistical sample of this department was determined based on Morgan's sampling table and 80 people were estimated to be selected by the use of the simple random sampling method. A questionnaire was used as the tool for the data collection. It was a researcher-made questionnaire containing 15 questions with closed answers, which includes two parts: the first part containing demographic questions (the first part of the questionnaire) related to the respondents’ general characteristics, e.g., gender, marital status, age; and the second part containing component-based attitudinal questions. According to the statistical sample, 80 questionnaires were distributed. However, in the initial review of the questionnaires, it was found that 70 people answered the questionnaire correctly and completely, and their data were used in the research analysis. A ranking scale was used to rank the research data. In this approach, the respondent is asked to indicate his/her agreement or disagreement with each item based on a spectrum. This scale makes it possible to determine the respondent’s sensitivity, reasoning, and belief. A 5-point Likert scale was used in the questionnaire, with the values of the scale factors ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (5).

Questionnaire Validity and Reliability

Questionnaire Validity

In this study, the content validity method was used to determine the questionnaire validity, as it is common to use this method in studies where the respondents must understand the influencing factors and answer the questionnaire questions according to their perception of these variables.

Given that the research tool was a questionnaire, subjects such as appropriate appearance, legible typing, number of questions, how to write and use appropriate words, accurate translation, grammatical points according to the culture, and grammatical structure were considered in this study. Finally, for face validity, the questionnaires were presented to several expert professors in the field of health economics and relevant doctors, and their opinions on them were asked and applied, and after taking the corrective measures, the questionnaires were approved.

Questionnaire Reliability

Reliability refers to the feature that if the measurement tool is given to the groups of people in the same conditions several times in a short period of time, the results will be close to each other. To measure the reliability, we used an index called “reliability coefficient”, and its size usually varies in the interval [0,1]. A reliability coefficient of 0 indicates no reliability and a reliability coefficient of 1 indicates complete reliability (Khaki, 2000).

The researcher can ask questionnaire questions to a few people using preliminary research. If people in the same conditions give the same answers to the questions questionnaire, it can be said that the questionnaire questions have a good reliability (Sarmad et al., 2007). In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to check the reliability of the measurement tool (the spectra).

This method is used to calculate the internal consistency of the measurement tool that measures different characteristics. To calculate the Cronbach's alpha coefficient, first, the variance of the scores of each subset of the questions and the total variance must be calculated. Then, using Cronbach's alpha coefficient formula, the alpha coefficient values are calculated. The Cronbach's alpha values derived and the number of questions of each index and the entire questionnaire are presented in Table 2.

Table 1: Cronbach's alpha values and the number of questions of each index and the entire questionnaire.

| Index | Number of questions | Cronbach’s alpha coefficient | |

| Physician-induced demand | Patient’s low information | 5 | 0.816 |

| Physician’s high information | 5 | 0.708 | |

| High costs of HPOs | 5 | 0.719 | |

| Entire questionnaire | 15 | 0.748 | |

Resource: research findings, the coefficient derived indicates the reliability of the questionnaire.

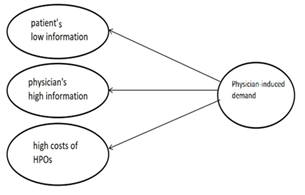

Conceptual Model of Research

The conceptual model of this research was proposed by applying theoretical foundations and based on the research model used in Sabatini Dwyer and Liu (2014) and the results of Keyvanara et al. (2013) and (2013). In this model, the factors affecting the physician-induced demand are considered as the independent variables and the physician-induced demand is also considered as the dependent variable.

Figure 1: Conceptual model of research.

According to the relationships between the variables of the research conceptual model, the following three hypotheses can generally be proposed:

The first hypothesis. Patient’s low information is positively correlated with physician-induced demand.

The second hypothesis. Physician’s high information is positively correlated with physician-induced demand.

The third hypothesis. High costs of healthcare provider organizations (HPOs) is positively correlated with physician-induced demand.

Data Analysis Method

The research method used in this study is survey-descriptive, and it is of applied type in terms of goal. In this research, descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the information extracted from the questionnaire. In the descriptive part, the subjects’ demographic characteristics, including gender, marital status, and age, are determined through frequency and percentage tables, as well as the mean and standard deviation; and in the inferential part, the data normality is obtained through the use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Then, the hypotheses will be analyzed using the Pearson correlation parametric test through the SPSS statistical analysis software.

Research Findings

Research Descriptive Findings

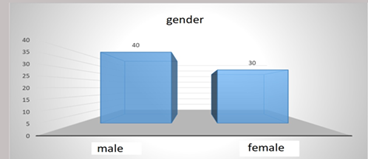

The subjects’ gender status is presented in Table 2 and draw in Figure 1, according which 57.1% of the subjects were men and 42.9% were women.

Table 2: Subjects' gender status

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative frequency |

| Male | 40 | 57.1 | 57.1 |

| Female | 30 | 42.9 | 100 |

| Total | 70 | 100 | 100 |

Resource: Research findings.

Figure 2: Subjects' gender status.

The subjects’ marital status is presented in Table 3 and draw in Figure 2, as it can be seen that 20% of the subjects are single and 80% married.

Table 3: Subjects' marital status.

| Marital status | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative frequency |

| Single | 14 | 20 | 20 |

| Married | 56 | 80 | 100 |

| Total | 70 | 100 | 100 |

Resource: Research findings.

Figure 3: Subjects' marital status.

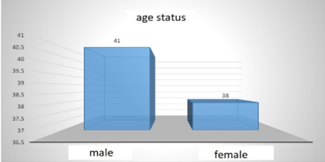

Table 4 and Figure 3 present the subjects’ condition in terms of age by gender, according to which the age of men (with an average of 41.08 years) is greater than the age of women (with an average of 38.8 years).

Table 4: Subjects’ age by gender status.

| Gender | Number | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | Standard error | |

| age | Male | 40 | 41.09 | 5.82 | 0.92 |

| Female | 30 | 38.8 | 4.37 | 0.79 |

Resource: Research findings.

Figure 4: Subjects’ age by gender status.

Table 5 lists the mean scores of the subjects in the research main variables, i.e., patient’s low information, physician’s high information, and high costs of HPOs. As can be seen, the mean scores derived are higher than the average score, i.e., 3, and on the other hand, the mean scores derived for men and women are almost identical.

Table 5: The mean scores of the subjects’ responses in terms of the variables of patient’s low information, physician’s high information, and high costs of HPOs, by gender.

| Gender | Number | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | Standard error | |

| Patient’s low information | Male | 40 | 3.52 | 0.6 | 0.09 |

| Female | 30 | 3.48 | 0.51 | 0.09 | |

| Physician’s high information | Male | 40 | 4.15 | 0.40 | 0.06 |

| Female | 30 | 4.16 | 0.51 | 0.09 | |

| High costs of HPOs | Male | 40 | 3.76 | 0.76 | 0.12 |

| Female | 30 | 3.74 | 0.82 | 0.15 |

Resource: Research findings

Research Inferential Findings

Before analyzing each of the hypotheses, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to measure the data normality, and the results are listed in Table 6.

Table 6: Results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to measure the data normality.

| Index | Patient’s low information | Physician’s high information | High costs of HPOs |

| Number | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Kolmogorov Smirnov's z-statistic | 0.885 | 1.265 | 0.846 |

| Significance level | 0.413 | 0.081 | 0.472 |

Resource: Research findings.

As can be seen in Table 6, a significance level greater than 0.05 has been derived for all the variables, indicating that according to the z-statistic, each of the variables of patient’s low information, physician’s high information, and high costs of HPOs are statistically significant are in a normal. Therefore, parametric tests can be used in the analysis of each hypothesis.

Analysis of Research Hypotheses

A) Analysis of the first hypothesis

Patient’s low information is positively correlated with physician-induced demand. In order to investigate the relationship between the patient's lack of information and the physician-induced demand, Pearson's correlation test was used, the results of which are listed in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7: Mean and standard deviation of the variables of patient’s low information and physician-induced demand in the subjects.

| Mean | SD | Number | |

| Physician-induced demand | 3.50 | 0.56 | 70 |

| Patient’s low information | 3.63 | 1.2 | 70 |

Resource: Research findings

Table 8: Pearson's correlation coefficient between the variables of patient's low information and physician-induced demand.

| Patient’s low information | ||

| Physician-induced demand | Pearson correlation | 0.350 |

| Significance level | 0.003 | |

| Number | 70 | |

Resource: Research findings.

As can be seen in Table 8, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the variables of physician-induced demand and patient's low information was obtained as r = 0.350, provided that P less than 0.01. Therefore, it can be said that the correlation between these two variables is significant with a confidence level of 99%. Therefore, considering the positive correlation coefficient, it can be concluded that patient’s low information leads to an increase in the physician-induced demand and vice versa. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is confirmed and hypothesis H0 is rejected, and the first hypothesis of the research is confirmed.

B) Analysis of the second research hypothesis

Physician’s high information is positively correlated with physician-induced demand. Pearson correlation test is used to investigate the relationship between physician’s high information and physician-induced demand, the results of which are presented in Tables 9 and 10.

Table 9: Mean and standard deviation of the variables of physician’s high information and physician-induced demand in the subjects.

| Mean | SD | Number | |

| Physician-induced demand | 3.50 | 0.56 | 70 |

| Physician’s high information | 3.63 | 1.2 | 70 |

Resource: Research findings.

Table 10: Pearson's correlation coefficient between physician’s high information and physician-induced demand.

| Physician’s high information | ||

| Physician-induced demand | Pearson correlation | 0.465 |

| Significance level | 0.000 | |

| Number | 70 | |

Resource: Research findings.

As can be seen in Table 10, Pearson's correlation coefficient between the variables of physician's high information and physician-induced demand is r 0.465, provided that P less than 0.01. Therefore, it can be said that the correlation between these two variables is significant with a confidence level of 99%. Therefore, according to the positive correlation coefficient, it can be concluded that as the physician's information increases, the physician-induced demand increases, and vice versa. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is confirmed and hypothesis H0 is rejected, and the second hypothesis of the research is confirmed.

C) Analysis of the third research hypothesis

High costs of healthcare provider organizations (HPOs) are positively correlated with physician-induced demand.

Pearson correlation test was used to investigate the relationship between the high costs of HPOs and the physician-induced demand, the results of which are listed un-Tables 11 and 12.

Table 11: Mean and standard deviation of the variables of high costs of HPOs and the physician-induced demand in the subjects.

| Mean | SD | Number | |

| Physician-induced demand | 3.50 | 0.56 | 70 |

| High costs of HPOs | 3.47 | 1.17 | 70 |

Resource: Research findings.

Table 12: Pearson's correlation coefficient between the variables of high costs of HPOs and physician-induced demand.

| High costs of HPOs | ||

| Physician-induced demand | Pearson correlation | 0.463 |

| Significance level | 0.000 | |

| Number | 70 | |

Resource: Research findings.

As can be seen in Table 12, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the variables of high costs of HPOs and physician-induced demand is equal to r = 0.463, provided that P less than 0.01. Therefore, it can be said that the correlation between these two variables is significant with a confidence level of 99%. Therefore, according to the positive correlation coefficient, it can be concluded that as the costs of HPOs increases, the physician-induced demand increases, and vice versa. Therefore, the hypothesis H1 is confirmed and the hypothesis H0 is rejected, and the third hypothesis of the research is confirmed as well.

Conclusions and Suggestions

The standard model used in the healthcare economics literature to investigate the agency relationship between healthcare providers and the patient and the effect of information asymmetry on the behavior of the supply side, i.e. the occurrence of supply side bias, is known as induced demand. In other words, the induced demand is a demand in addition to the patient's treatment needs, which is imposed on the patient by the healthcare deliberately (to earn more money) or undeliberately (due to lack of knowledge, experience, and skills), causing heavy expenses for him/her. For this reason, addressing this issue can be useful in order to reduce violations caused by the superficiality of healthcare service applicants, to reduce the tricks used by some healthcare providers to generate more income, and prevent unnecessary prescriptions. In developed countries, growing technology and various treatment methods are quickly integrated and used by physicians, while in developing countries such as Iran, this occurs at a much lower speed and with a limited number of physicians, which encourage physicians to create induced demand. Accordingly, determination of the factors affecting the induced demand is very effective and requires a lot of discussion and investigation; this made the researchers of the current study to investigate this issue in general (a task that was proposed in the previous research only for one of the indicators affecting the induced demand) and the following results were obtained:

The indicators of patient’s low information, physician’s high information, and high costs of HPOs have a positive effect on the supplier-induced demand in healthcare services, or especially suppliers of treatment technologies such as CT scan. Therefore, as the patient’s information decreases, the physician’s information and the costs of HPOs increase, leading to an increase the supplier-induced demand, and the existence of induced demand is confirmed. In addition, the variable of high costs of HPOs (r = 0.463) plays a more significant role in increasing the supplier-induced demand than the other two variables do. In general, the results obtained in this research (factors affecting the induced demand of health care providers) can be considered to be aligned with the results of Khorasani et al. (2013), Abdulli and Varahrami (2010), Varahrami (2009) and Sekimoto et al. (2015). On this basis and considering the results of this study, it is suggested to increase the society’s awareness with the aim of controlling the induced demand, to monitor the financial incentives of the HPOs with the help of appropriate control policies, and to keep track of physicians’ performance. Also, paying attention to patients’ dignity and needs, increasing information, increasing patients’ information about treatment and medicine, and passing laws and standards related to physicians’ performance by the medical system organization can also play a significant role in reducing the induced demand.

References

- Panahi H., Salmani B., Nasibparast S. (2015). Investigating the induced effect of the number of physicians and hospital beds on health expenditure in Iran. Quarterly journal of applied theories of economics, 2(2):25-42.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Khorasani, E., Kivanara, M., Karimi, S., Jafarian Jozi, M. (2013). Understanding the role of patients in induced demand from the perspective of experts: a qualitative study. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences, 2(4):336-345.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kivanara, M., Karimi, S., Khorasani, E., Jafarian Jozi, M. (2014). Do healthcare provider organizations play a role in the induced demand phenomenon? A qualitative study? Journal of Faculty of Paramedicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, 8(4):280-293.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kivanara, M., Karimi, S., Khorasani, E., Jafarian Jozi, M. (2014). Challenges arising from induced demand for health services: A qualitative study. Health Information Management, 10(4):538-548.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kivanara, M., Karimi, S., Khorasani, E., Jafarian Jozi, M. (2013). The opinion of health system experts about the macro factors affecting inducted demand: A qualitative study. Hakim Research Journal, 16(4):317-328.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bridges JF, Jones C. (2007). Patient-based health technology assessment: a vision of the future. Int J Technol Assess Health Care, 23(1):30-35.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dranove, David., Wehner, Paul. (1994). Physician-induced demand for childbirths, Journal of Health Economics, 13:61-73.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Grytten, Jostein., Carlsen, Fredrik., Skau, Irene. (2010). The income effect and supplier induced demand. Evidence from primary physician services in Norway, Applied Economics, 3:(11):1455-1467.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Izumida, Nobuyuki., Urushi, Hiroo., Nakanishi, Satoshi. (1999). An Empirical Study of the Physician-Induced Demand Hypothesis: The Cost Function Approach to Medical Expenditure of the Elderly in Japan. Review of Population and Social Policy, 8:11-25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Palesh M, Tishelman C, Fredrikson S, Jamshidi H, Tomson G, Emami A. (2010). We noticed that suddenly the country has become full of MRI. Policy makers’ views on diffusion and use of health technologies in Iran. Health Res Policy Syst, 8:9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sabatini Dwyer, Debra., Liu, Hong. (2013). The impact of consumer health information on the demand for health services. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 53:1-11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sekimoto, Miho., MPH., Ii, Masako. (2015). Supplier Induced Demand for Chronic Disease Care in Japan: Multilevel Analysis of the Association between Physician Density and Physician-Patient Encounter Frequency. Value in Health Regional, 6c:103-110.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Woo Lee, Yong. (2012). Asymmetric information and the demand for private health insurance in Korea, Economics Letters, 116:284-287.

Publisher | Google Scholor