Case report

Acute Pulmonary Embolism with Multiple Septic Emboli and Pulmonary Infarcts in an IV Drug Abuser with Right-Sided Endocarditis: A Case Report

- Anup Regmi

- Nirmal Prasad Neupane *

- Aishath Naura

- Kritisha Rajlawot

Radiologist, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Bansbari, Kathmandu, Nepal.

*Corresponding Author: Nirmal Prasad Neupane, Radiologist, EDIR Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Citation: A Regmi, Nirmal P Neupane, A Naura, K Rajlawot. (2023). Acute Pulmonary Embolism with Multiple Septic Emboli and Pulmonary Infarcts in an IV Drug Abuser with Right-Sided Endocarditis: A Case Report. International Journal of Medical Case Reports and Reviews, BRS Publishers.2(1); DOI: 10.59657/2837-8172.brs.23.007

Copyright: © 2023 Nirmal Prasad Neupane, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: December 14, 2022 | Accepted: February 23, 2023 | Published: February 10, 2023

Abstract

This case report describes the imaging findings of septic pulmonary embolism (SPE) in a 30-year-old male with a history of intravenous drug abuse for one year. The patient initially presented with high grade fever, shortness of breath, and cough in the emergency department of our institution. The patient was evaluated by chest X-ray, blood cultures, echocardiography, and CT pulmonary angiography which confirmed the diagnosis of SPE, and the causative organism was confirmed to be Staphylococcus aureus. In this case report, we discuss the Chest X-ray findings, and characteristic CT imaging findings of SPE and describe the role of different imaging modalities in the timely diagnosis and management of this highly fatal condition.

Keywords: acute pulmonary embolism; emboli; pulmonary infarcts; iv drug; abuser; endocarditis

Introduction

Septic pulmonary embolism (SPE) refers to the embolization of infected thrombi containing microorganisms from a primary site of infection into the pulmonary vasculature leading to parenchymal infection [1,5]. The thrombi cause mechanical blockage of arteries producing inflammatory reactions within them. The patient may present with fever, cough, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, or acute sepsis syndrome [1].

Pulmonary septic emboli are frequent complications of right-sided bacterial endocarditis, septic thrombophlebitis, osteomyelitis, infected indwelling catheters or devices, odontogenic infections, skin and soft tissue infections, alcoholism, patients with AIDS, patients undergoing organ transplantation, and patients receiving chemotherapy for malignancy [2, 3, 4, 5]. However, septic emboli most commonly originate from cardiac valves in patients with infective endocarditis associated with intravenous drug abuse. Approximately one third of intravenous drug abusers having bacteremia will develop infective endocarditis [7]. Right-sided infective endocarditis is commonly associated with intravenous drug abuse with the most common source of septic embolism being the infective foci in the right heart (e.g., Tricuspid vegetation in infective endocarditis) [7]. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of tricuspid valve endocarditis [5, 9]. Radiographic imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of septic pulmonary embolism (PE), in addition to clinical evaluation and laboratory findings. SPE has unique imaging findings on computed tomography (CT), which helps in timely and accurate diagnosis [3]. Appropriate antibiotics should be immediately administered after diagnosis of septic pulmonary embolism followed by supportive and/or interventional management, depending on the severity of complications as SPE has a high mortality rate [5].

Case Report

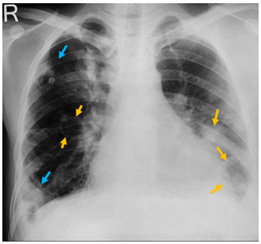

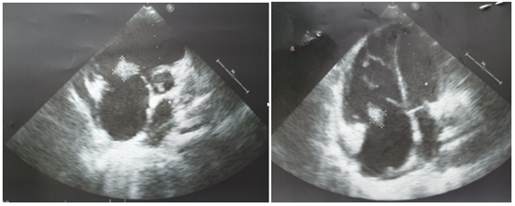

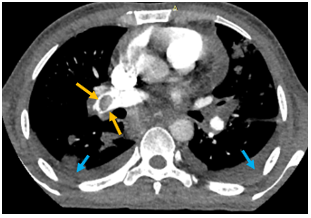

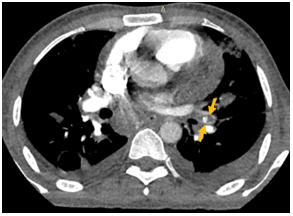

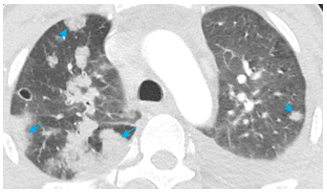

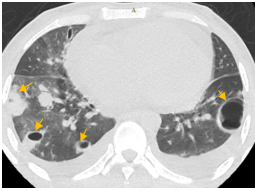

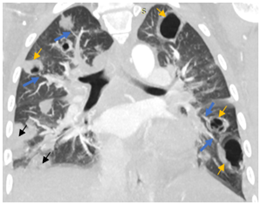

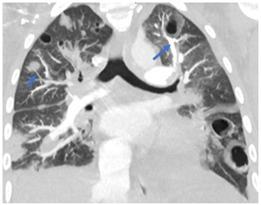

A 30-year-old male with a history of intravenous drug abuse for one year presented in the emergency department of our institution with complaints of fever with chills and rigor for one week, cough for 2 weeks, and tachypnea for 3 days. Blood was sent to the laboratory for culture which turned out positive for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Chest X-ray demonstrated multiple ill-defined fluffy nodular opacities in bilateral lungs that were both centrally and peripherally located (Fig. 1). Cavitary changes were noted in few of them. Blunting of bilateral costophrenic angle suggestive of bilateral pleural effusion was noted (Fig.1). Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated large swinging vegetations attached to anterior and posterior leaflets of tricuspid valve with the largest vegetation measuring 2.1 x1.2 cm in size (indicating infective endocarditis) (Fig.2). CT pulmonary angiography demonstrated non-enhancing hypodense filling defects in the distal right main pulmonary artery and left inferior lobar pulmonary artery suggestive of pulmonary emboli (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Pulmonary parenchymal findings revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules (most of them peripherally based) with central cavitation in few of them. A few of the nodules showed pulmonary vessels extending up to the margin of the nodule giving rise to the 'feeding vessel sign’ (Fig 8). Multiple bilateral peripheral wedge-shaped opacities suggestive of pulmonary infarcts were noted (Fig 5). Mild bilateral pleural effusion was seen (Fig. 3). Antibiotic therapy was initiated with intravenous Vancomycin along with supportive measures. The patient's condition gradually improved with antibiotics and following the completion of antibiotic therapy with supportive care, the patient was discharged from the hospital in 6 weeks.

Figure 1: Chest X-ray posteroanterior erect view showing peripheral wedge-shaped opacities (blue arrows) and cavitary lesions (yellow arrows) in bilateral lungs. Blunting of bilateral costophrenic angles suggestive of bilateral pleural effusion is noted.

Figure 2A&B: Transthoracic echocardiogram showing large vegetations attached to tricuspid valve leaflets.

Figure 3: Contrast CT chest showing non-enhancing hypodense filling defect (embolism) in the right main pulmonary artery with surrounding rim of enhancement (yellow arrows).

Figure 4: Non-enhancing filling defect (embolus) in the left inferior lobar pulmonary artery. Mild bilateral pleural effusion (blue arrows).

Figure 5: CT chest (lung window, axial view) showing multiple peripheral wedge-shaped lesions (blue arrows) in bilateral lungs.

Figure 6: Peripheral nodular lesions with central cavitation in bilateral lungs (yellow arrows).

Figure 7: CT chest (lung window, coronal view) showing multiple nodular lesions in bilateral lungs with central cavitation (yellow arrows). Peripheral wedge-shaped opacities are noted in right lung (black arrows). Pulmonary vessels are supplying some of the cavitary lesions showing “feeding vessel sign” (blue arrows).

Figure 8: Pulmonary vessel leading to cavitary lesion in the upper lobe of left lung and a pulmonary vessel leading to a peripheral nodular opacity in right lung (arrows).

Discussion

Septic pulmonary embolism is a dreaded complication in patients with right sided endocarditis [11]. It has a high mortality wherein death is commonly found to be caused by septic shock accompanied by multiple organ failures [10]. The main causes of SPE are identified to be pneumonia, sepsis, and infective endocarditis. Right-sided infective endocarditis is noted among intravenous drug abusers [9]. About 75% of cases of SPE are seen to be associated with right-sided infective endocarditis secondary to IV drug abuse [1]. The landmark lesion of infective endocarditis is vegetation in the heart. Intravenous drug users with vegetation measuring >20 mm present with a higher risk of embolism and higher mortality [9]. Typical chest radiographic features of SPE include patchy air space lesions in lungs simulating nonspecific bronchopneumonia; multiple ill-defined round or wedge-shaped densities of varying sizes located peripherally, pleural effusion, empyema, bronchopleural fistula, pneumothorax, and hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement [2, 10]. However, chest radiograph findings are non-specific and have low sensitivity in the diagnosis of SPE. The characteristic findings on CT scan include bilateral discrete nodules of varying size and varying degrees of cavitation. Sometimes a 'feeding vessel sign' can be identified in patients with septic emboli (a distinct vessel leading directly to a nodule) which is considered by some to be pathognomic of SPE. Pleural effusion or empyema may occasionally complicate SPE [6,7,8]. Early diagnosis and prompt administration of antibiotic therapy are the main determinants of outcome in patients having septic pulmonary emboli [3]. After the diagnosis of SPE, appropriate antibiotics should be immediately instituted with supportive and/or interventional management as per requirement [5]. Initially, empiric antibiotics should be started (initially glycopeptides and then the addition of broad-spectrum antibiotics). Antibiotics can then be modified according to the culture results and should be continued for a minimum of 4-6 weeks, guided by clinical, lab, and imaging findings [1]. In selected cases, surgical intervention or thoracostomy drainage may also be indicated [3].

Conclusion

Septic pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening complication associated with right-sided infective endocarditis secondary to IV drug abuse. Patients having clinical suspicion of SPE should be evaluated by blood cultures, echocardiography, and CT imaging of the chest including CT pulmonary angiography. Every emergency physician, cardiologists and radiologists should be aware of the spectrum of imaging findings associated with this complication. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent mortality associated with septic pulmonary embolism as the condition is highly fatal.

Declarations

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all involved in this study for their contribution.

Author contributions

Dr. Anup Regmi and Dr. Nirmal Prasad Neupane - analyzed and interpreted the patient data.

Dr. Aishath Naura - major contributor in writing the manuscript.

Dr. Kritisha Rajlawot - collection of imaging findings and structuring them in the case report.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report did not require review by the Ethical committee for publication.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Declaration of competing interests

All of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Goswami U, Brenes JA, Punjabi GV, Le Claire MM, Williams DN. (2014). Associations and outcomes of septic pulmonary embolism. The open respiratory medicine journal. 8(28).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wong KS, Lin TY, Huang YC, Hsia SH, Yang PH, Chu SM. (2002). Clinical and radiographic spectrum of septic pulmonary embolism. Archives of disease in childhood. 87(4):312-315.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shahin Owji, BS, Woongsoon J. Choi, DO, Esraa Al-Jabbari, MD, Kalpana Manral, MD, Diana Palacio, MD, Peeyush Bhargava, MD MBA. (2022). Computed tomography findings in septic pulmonary embolism: A case report and literature review. Science direct Elsevier.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Iwasaki Y, Nagata K, Nakanishi M, Natuhara A, Harada H, Kubota Y, Yokomura I, Hashimoto S, Nakagawa M. (2001). Spiral CT findings in septic pulmonary emboli. European journal of radiology. 37(3):190-194.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yellapu V, Ackerman D, Longo S, Stawicki SP. (2018). Septic embolism in endocarditis: Anatomic and pathophysiologic considerations. In Advanced Concepts in Endocarditis. Intech Open.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Swain S, Ray A. (2021). Septic pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Reports CP. 14(10):e246306.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shah T, Hari P, Desai P. A Study of Radiological Appearances of Septic Pulmonary Embolism in Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography Thorax.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dodd JD, Souza CA, Müller NL. (2006). High-resolution MDCT of pulmonary septic embolism: evaluation of the feeding vessel sign. American Journal of Roentgenology. 187(3):623-629.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Horatiu M, Molnar A, Costache V, Bontas E. (2019). Infective Endocarditis in Intravenous Drug Users: Surgical Treatment. InInfective Endocarditis, IntechOpen.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ye R, Zhao L, Wang C, Wu X, Yan H. (2014). Clinical characteristics of septic pulmonary embolism in adults: a systematic review. Respiratory medicine. 108(1):1-8.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kwon WJ, Jeong YJ, Kim KI, Lee IS, Jeon UB, Lee SH, Kim YD. (2007). Computed tomographic features of pulmonary septic emboli: comparison of causative microorganisms. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 31(3):390-394.

Publisher | Google Scholor