Research Article

A Study on Bacterial Causes of Mastitis and their Antimicrobial Drug Resistance in Bareilly, North India

- Bhoj Raj Singh

- Akanksha Yadav

- Dharmendra Kumar Sinha

- Ravichandran Karthikeyan

- Himani Agri

- Varsha Jayakumar

Division of Epidemiology, ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, India.

*Corresponding Author: Bhoj Raj Singh, Division of Epidemiology, ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, India.

Citation: Bhoj R. Singh, Yadav A, Dharmendra K. Sinha, Karthikeyan R, Agri H, et al. (2024). A study on bacterial causes of mastitis and their antimicrobial drug resistance in Bareilly, North India. International Clinical and Medical Case Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(2):1-14. DOI: 10.59657/2837-5998.brs.24.035

Copyright: © 2024 Bhoj Raj Singh, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: January 25, 2024 | Accepted: February 16, 2024 | Published: March 06, 2024

Abstract

Mastitis is a multi-etiological inflammation of mammary glands affecting mammals and a big challenge to clinicians. In the present study, from 122 mastitis cases, milk samples were processed for isolation, identification of bacteria and antimicrobial susceptibility assay using standard bacteriological methods. Of the 317 isolates of bacteria belonging to 77 species that were isolated from mastitis milk 63.09%, 47.95%, 47.95% and 17% had multiple drug resistance, extended-spectrum β-lactamase production potential, multiple herbal drug resistance and carbapenem drug resistance, respectively. From 61 cases of mastitis, only a single type of bacteria was incriminated as the cause of mastitis, of these, in 12 cases Gram -ve bacteria (8 Escherichia coli, 2 Klebsiella pneumoniae, 1 Kluyvera cryocvresacens, and 1 Roultella terrigena), and 49 cases Gram +ve bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus 5, S. epidermidis 4, S. haemolyticus 3, S. intermedius 3, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 2, S. hyicus 2, S. caprae 1, S. caseolyticus 1, S. delphini 1, S. lugdunensis 1, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans 1, S. warneri, Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisiumilis, S. intestinalis 5, S. milleri 4, S. agalactiae 3, S. pyogenes 3, and S. uberis 1) were responsible. In buffaloes, the most common single cause of mastitis was E. coli and S. milleri; in cows, they were S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis and Streptococcus intestinalis. Enrofloxacin, amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, and ampicillin inhibited only 60-70% of the bacterial strains. The major limitation of the study was that samples from only clinical mastitis cases coming for treatment were analysed while subclinical mastitis is more common. The study concludes that for effective antimicrobial therapy bacteriological analysis should be undertaken for effective clinical management of mastitis.

Keywords: ESBL; MDR; carbapenem resistance; staphylococci; streptococci; E. coli; roultella terrigena; streptococcus milleri

Introduction

Mastitis is an economically devastating painful disorder in most of the milch animals. In India, the average economic loss due to mastitis was estimated to be Rs.1390 per lactation in cattle and cost of treating mastitis in animals was Rs. 509 per animal [1]. Mastitis is a multi-aetiological problem but, in most cases, bacterial infections either as primary cause or as secondary invaders are the most important [2-4]. Though viruses, mycoplasma, fungi and bacteria of many species may cause mastitis in bovines, bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus zooepidemicus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Enterococcus faecalis, Mycobacterium bovis, Klebsiella aerogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Brucella abortus, Pasteurella multocida, Pseudomonas pyocyaneus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica ssp. enterica and Leptospira Pomona are considered more important [4-13]. Some less common bacteria causing mastitis are Aerococcus viridans, Acinetobacter spp., Staphylococcus haemolyticus, and Bacillus licheniformis [14]. In India, Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. and Escherichia coli were responsible for 45%, 13% and 14

Materials and Methods

Milk samples from clinical cases of mastitis

Over a period of six years (2017-2023) a total of 122 milk samples from cases of mastitis were received in Clinical Epidemiology Laboratory from Referral Veterinary Polyclinic (cows 80, buffaloes 33, bitches 4, goats 4) and Human Hospital (a woman) of the Institute for bacteriological analysis for identification of the causal organism and to find out the effective antimicrobial agent to institute the therapy. All the samples were processed as per standard protocol for the identification of aerobic and micro-aerobic bacteria [26]. Briefly, 3-5 isolated colonies were picked up from the blood agar plates and or McConkey agar plates inoculated with a loop-full of milk samples and incubated for 24-48h at 37°C aerobically and micro-aerobically and identified using growth, morphological and biochemical characteristics [27, 28] and also confirmed using MALDITOF-MS profile where so ever there was any confusion. All the pure culture isolates were maintained on nutrient agar slants and glycerol broth [28] till the end of the study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility assays

All bacterial isolates were tested for their susceptibility to amoxicillin +clavulanic acid (30+10 µg), amoxicillin (30 µg), ampicillin (30 µg), azithromycin (15 µg), aztreonam (30 µg), cefepime (30 µg), cefotaxime(30 µg), cefotaxime + clavulanic acid (10 +10 µg), cefoxitin (10 µg), ceftriaxone (10 µg), chloramphenicol (25 µg), ciprofloxacin (10 µg), colistin (10 µg), cotrimoxazole (25 µg), doxycycline (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), gentamicin (30 µg), imipenem (10 µg), lincomycin (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg), nitrofurantoin (300 µg), piperacillin (100µg), piperacillin + tazobactam (100 + 10 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), tigecycline (15 µg) and vancomycin (30 µg) discs (Difco, USA) following CLSI guidelines [29, 30] on Mueller Hinton agar (MHA, Difco) plates. All incubations were carried out aerobically at 37°C for 18-24 h; the diameter of growth inhibition zone around discs was measured in mm and interpreted as per CLSI guidelines [29, 30]. One strain each of Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC43300) and Escherichia coli (E-382) were used as the control reference strain. Bacterial isolates having similar susceptibility patterns were considered as single strains and isolates resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials were classified as multi-drug-resistant (MDR). For confirming extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production by bacterial isolates ESBL-E-test strips (Biomerieux, France) were used as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. All bacterial isolates were also tested for their herbal antimicrobial susceptibility using disc diffusion assay [31] against discs containing 1µL of test herbal antimicrobial viz., ajowan (Trachyspermum ammi) oil, carvacrol (Sigma, USA), cinnamaldehyde (Sigma, USA), Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) oil, citral (Sigma, USA), guggul (Commiphora mukul) oil, holy basil (Ocimum sanctum) oil, lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) oil, and thyme (Thymus vulgaris) oil. Except guggul oil all herbal oils were procured with >99.5% purity from Shubh Flavours and Fragrance Ltd, New Delhi. The pure guggul oil was received as a kind gift from Dr. MZ Siddiqui, Processing and Product Development Division, ICAR - Indian Institute of Natural Resins & Gums, Namkum, Ranchi, India. Any measurable zone of growth inhibition around the herbal disc measured in mm was taken as an antimicrobial activity indicator. Bacterial isolates with no measurable zone of growth inhibition (ZI) were classified as resistant. Isolates resistant to more than two herbal antimicrobials were grouped as multiple herbal antimicrobial-resistant.

Statistical analysis

Data on bacterial isolates for their source of isolation and their susceptibility to different antimicrobials was line entered in an Excel sheet for analysis using for Chi-square test to understand various relations among different factors.

Results

Of the 122 samples of mastitis milk from cows (80), buffaloes (33), bitches (4), goats (4) and one woman, 317 isolates of bacteria belonging to 77 species and subspecies were identified (Tab. 1). Staphylococci strains were detected in 78 (63.93%) samples and belonged to 21 species and subspecies including Staphylococcus aureus 20 (16.39%), S. capitis ssp. capitis 1, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 2, S. caprae 2, S. caseolyticus 2, S. chromogenes 2, S. cohnii ssp. cohnii 1, S. delphini 2, S. epidermidis 11 (9.02%), S. gallinarum 1, S. haemolyticus 10 (8.20%), S. hominis 1, S. hyicus 5 (4.1%), S. intermedius 8 (6.56%), S. kloosii 1, S. lugdunensis 2, S. saccharolyticus 1, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans 1, S. schleiferi ssp. schleiferi 1, S. warner 1 and S. xylosus 1. Streptococci were the second most common group of bacteria identified from 48 (39.34%) samples. They belonged to 14 species and subspecies including S. agalactiae 5 (4.10%), S. anginosus 1, S. bovis 2, S. dysgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae 5 (4.10%), S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis 8 (6.56%), S. intestinalis 5 (4.10%), S. milleri 7 (5.74%), S. morbilorum 1, S. phocae 1, S. pneumoniae 1, S. pyogenes 8 (6.56%), S. sanguinis 1, S. solitarius 1 and S. uberis 2. The third most common bacteria detected in mastitis milk samples was Escherichia coli detected in 29 (23.77%) samples, followed by K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae isolated from 12 (9.84) samples. Overall, E. coli was the most commonly identified species of bacteria detected in 29 samples followed by S. aureus (20), K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae (12), S. epidermidis (11), S. haemolyticus (10), S. intermedius (8), Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis (8), S. pyogenes (8), S. milleri (7), Pantoea agglomerans (6), S. hyicus (5), S. agalactiae (5), S. dysgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae (5), S. intestinalis (5), and other bacteria were isolated from less than 5 cases only. Of the 122 cases, 61 had only single type of bacteria (Tab. 2, 3), 12 had Gram -ve bacteria (8 by E. coli, 2 by K. pneumoniae, and one each by K. cryocvresacens and R. terrigena) and 49 cases yielded one or other Gram +ve bacteria (27 staphylococci, 21 streptococci and 1 Paenibacillus macerans). Of the 61 cases having single type of bacteria in milk samples, 27 (22.13%) had staphylococci of 12 species and subspecies including S. aureus 5 (4.10%), S. epidermidis 4, S. haemolyticus 3, S. intermedius 3, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 2, S. hyicus 2 and one each of S. caprae, S. caseolyticus, S. delphini, S. lugdunensis, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans, and S. warneri. A total of 21 (17.21%) cases of mastitis had Streptococcus strains as single bacteria, five each had S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisiumilis and S. intestinalis while four had S. milleri, three each had S. agalactiae and S. pyogenes and one had S. uberis. From an equal number of milk samples from mastitis cases (61) more than one type (2 to 7) of bacteria was detected simultaneously (Tab. 2 and Fig. 1, 2). In Buffaloes (Fig. 1), the probability of isolation of a single type of bacteria from mastitis milk samples was significantly (p, 0.01) higher than isolation of two types or three types of bacteria. In Cows (Fig. 2), the probability of isolation of a single type of bacteria from mastitis milk samples was significantly (p, <0>

Table 1: Bacteria isolates from milk samples of mastitis cases in different species.

| Types of bacteria | Bacteria detected in milk samples of different sources | % Samples positive | |||||

| Buffalo (n=33) | Cows (n=80) | Bitches (n=4) | Goats (n=4) | Human (n=1) | Total (N=122) | ||

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Acinetobacter lwoffii | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aerococcus sanguinicola | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Aeromonas bestiarum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aeromonas caviae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aeromonas jandei | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aeromonas salmonicida ssp. salmonicida | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aeromonas salmoicida ssp. smithia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Aeromonas schubertii | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Alcaligenes denitrificans | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.46 |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.28 |

| Bacillus cereus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Enterococcus avium | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.46 |

| Enterococcus malodoratus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Erwinia amylovora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Erwinia stewartii | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Erwinia psidii | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Escherichia coli | 11 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 23.77 |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 9.84 |

| Kluyvera cryocrescens | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Mammaliicoccus lentus | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Mammaliicoccus sciuri | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.46 |

| Micrococcus luteus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.28 |

| Moraxella osloensis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Paenibacillus macerans | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Pantoea agglomerans | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4.92 |

| Pasteurella species similar to canine oral Pasteurella | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Pectobacterium cyperipedii | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Pediococcus spp. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Proteus vulgaris | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Providencia rettgeri | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.28 |

| Raoultella terrigena | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2.46 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 7 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 16.39 |

| Staphylococcus capitis ssp. capitis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus capitis ssp. urealyticus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Staphylococcus caprae | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Staphylococcus caseolyticus | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Staphylococcus chromogenes | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Staphylococcus cohnii ssp. cohnii | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus delphini | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 9.02 |

| Staphylococcus gallinarum | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 8.20 |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus hyicus | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4.10 |

| Staphylococcus intermedius | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6.56 |

| Staphylococcus kloosii | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Staphylococcus saccharolyticus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus schleiferi ssp. coagulans | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus schleiferi ssp. schleiferi | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus warneri | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Staphylococcus xylosus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4.10 |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus bovis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4.10 |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6.56 |

| Streptococcus intestinalis | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4.10 |

| Streptococcus milleri | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5.74 |

| Streptococcus morbilorum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus phocae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 6.56 |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus solitarius | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Streptococcus uberis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.64 |

| Xenorhabdus poinarii | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Xenorhabdus bovienii | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.82 |

Table 2: Types of bacteria detected in different milk samples of mastitis cases

| Sources | Types of bacteria detected in milk samples from mastitis cases | ||||||

| Single | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven | |

| Buffaloes (n=33) | 17 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cows (n=80) | 39 | 21 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bitches (n=4) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Goats (n=4) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Woman (n=1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (n=122) | 61 | 31 | 18 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Table 3: Bacteria isolated in pure culture from mastitis milk samples of different origin

| Bacteria detected | Number of samples positive | Bacteria detected | Number of samples positive |

| Buffaloes (n= 33) | 17 | Cows (n= 80) | 39 |

| Escherichia coli | 4 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis | 5 |

| Streptococcus milleri | 4 | Streptococcus intestinalis | 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | Escherichia coli | 4 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 2 | Staphylococcus aureus | 4 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 2 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 3 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae | 1 | Staphylococcus hyicus | 3 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 1 | Staphylococcus intermedius | 3 |

| Staphylococcus capitis ssp. urealyticus | 1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae | 1 |

| Kluyvera cryocrescens | 1 | ||

| Bitches (n= 4) | 2 | Paenibacillus macerans | 1 |

| Raoultella terrigena | 1 | Staphylococcus capitis ssp. urealyticus | 1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | Staphylococcus caprae | 1 |

| Staphylococcus caseolyticus | 1 | ||

| Goats (n= 4) | 2 | Staphylococcus delphini | 1 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 1 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 1 | Staphylococcus schleiferi ssp. coagulans | 1 |

| Staphylococcus warneri | 1 | ||

| Woman (n= 1) | 1 | Streptococcus agalactiae | 1 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 | Streptococcus uberis | 1 |

Figure 1: Multiplicity of aetiology of mastitis cases in Buffaloes.

Figure 2: Multiplicity of aetiology of mastitis cases in cattle.

Table 4: Different groups of bacteria detected in milk samples from cases of mastitis

| Groups of bacteria (detected in samples) | Source of sample | Source wise samples positive for |

| Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. (17) | Buffaloes 4, Cows 11, Bitches 2 | Buffaloes (S. aureus 2, S. epidermidis 1, M. sciuri 1), Cows (S. aureus + S. caprae ssp. caprae 1, S. aureus + S. epidermidis 1, S. caprae ssp. urealyticus 1, S. chromogenes 1, S. caseolyticus + S. chromogenes 1, S. cohnii ssp. cohnii 1, S. epidermidis 1, S. hominis 1, S. hyicus 1, S. intermedius 1, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans 1,), Bitches (S. aureus 1, S. hyicus 1) |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. (13) | Buffaloes 6, Cows 6, Bitches 1 | Buffaloes (S. aureus 3, S. epidermidis 1, S. areus + S. epidermidis 1, S. sacchrolyticus 1), Cows (S. caseoyticus 1, S. epidermidis 1, S. aureus + S. epidermidis 1, S. intermedus 2, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans 1, S. hominis 1, M. lentus 1, S. chromogenes + S. intermedius 1), Bitch (1 S. lugdunensis) |

| Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. (17) | Cows 2 | Cows (A. facalis 1, A. faecium 1) |

| Vancomycin-resistant + Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. (3) | Cows 2 | Cows (S. epidermidis 2) |

| Gram +ve carbapenem-resistant bacteria (13) | Buffaloes 7, Cows 5, Bitch 1 | Buffaloes (Micrococcus luteus 1, S. aureus 2, S. aureus + S. epidermidis 1, S. milleri 2, S. pneumoniae 1), Cows (E. faecalis 1, E. faecium 1, S. milleri 1, S. aureus 1, S. caseolyticus 1), Bitch (S. lugdunensis 1) |

| Gram -ve carbapenem-resistant bacteria (13) | Buffaloes 4, Cows 7, Goat 1 | Buffaloes (E. coli 2, E. coli + A. lwoffii 1, P. mirabilis+ P. vulgaris 1), Cows (E. coli 4, A. faecalis 1, A. denitrificans +P. cyperipedii 1, A. denitrificans + B. cepacia 1), Goat (A. caviae 1) |

| All carbapenem-resistant bacteria (24) | Buffaloes 10, Cows 12, Bitch 1, Goat 1 | One sample from a buffalo had both G+ and G- CRB (E. coli, A. lwoffii and M. luteus) |

Samples with Vancomycin-resistant + Methicillin-resistant +Carbapenem-resistant bacteria (7) | Buffaloes 4, Cows 2 | Buffaloes (S. aureus 3, S. epidermidis 1), Cows (S. aureus 1, S. caseolyticus 1), Bitch (S. lugdunensis 1) |

| Bitch 1 | ||

| Vancomycin-resistant + Carbapenem-resistant bacteria (1) | Cow 1 | Cow (E. faecalis) |

| Gram +ve extended spectrum β-lactamase producers (44) | Buffalo 12, Cows 29, Bitches 2, Human 1 | Buffalo (B. subtilis 1, M. sciuri 2, S. aureus 3, S. apitis ssp. urealyticus 1, S. epidermidis 2, S. haemolyticus 2, S. kloosii 1, S. sysgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae 1, S. sysgalactiae ssp. equisilis 1, S. pyogenes 1), Cows (A. sanguinicola 1, E. faecalis 1, E. malodoratus 1, M. sciuri 1, M. luteus 1, Pediococcus spp. 1, S. aureus 7, S. capitis ssp. capitis 1, S. caseolyticus 1, S. chromogenes 2, S. epidermidis 3, S. haemolyticus 3, S. hominis 1, S. hyicus, S. intermedius 4, M. lentus 1, S. schleiferi ssp. schleiferi 1, S. warneri 1, S. bovis 2, S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis 3, S. pyogenes 4, S. sanguinis 1, S. uberis 1), Bitches (S. aureus 1, S. hyicus 1), Human (s. pyogenes 1) |

| Gram -ve extended spectrum β-lactamase producers (40) | Buffalo 14, Cows 24, Bitch 1, Goat 1 | Buffaloes (A. lwoffii 1, A. hydrophila 1, A. denitrificans 1, E. amylovora 1, E. psidii 1, E. coli 10, K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae 1, P. agglomerans, P. mirabilis 1, P. vulgaris 1), Cows (A. jandei 1, A. salmonicida ssp. salmonicida 1, A. denitrificans 2, E. coli 11, K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae 9, K. crocresacens 1, M. osloensis 1, P. agglomerans 2, P. canis 1, P. cyperipedii 1, P. rettgeri 1, P. aeruginosa 1, R. terrigena 1, X. bovienii 1, X. poinarii 1), Bitches (A. faecalis 1, E. coli 1), Goat (R. terrigena 1) |

| Enterobacteriaceae (46) | Buffaloes 15, Cows 28, Bitches 2, Goat 1 | Buffaloes (E. amylovora 1, E. psidii 1, E. coli 11, K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae 1, P. agglomerans 3, P. mirabilis 1, P. vulgaris 1), Cows (E. stewartii 1, E. coli 17, K. aerogenes 1, K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae 11, K. crycrescens 1, P. agglomerans 3, P. cyperipedii 1, P. rettgeri 1, R. terrigena 1, X. bovienii 1, X. poinarii 1), Bitches (e. coli 1, R. terrigena 1), Goat (R. terigena 1) |

| Gram +ve cocci (99) | Buffaloes 24, Cows 69, Bitches 3, Goats 2, Human 1 | Buffaloes (E. avium 1, M. luteus 2, S. aureus 7, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 1, S. delphini 1, S. epidermidis 4, S. haemolyticus 2, S. kloosii 1, S. sacchrolyticus 1, S. agalactiae 2, S. anginosus 1, S. dusgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae 1, S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis 1, S. milleri 5, S. morbilorum 1, S. phocae 1, S. pneumoniae 1, S. pyogenes 2), Cows (A. sanguinicola 2, E. faecalis 1, E. faecium 3, E. malodoratus 1, M. luteus 1, Pediococcus spp. 1, S. aureus 12, S. capitis ssp. capitis 1, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 1, S. cparae 2, S. caseolyticus 2, S. chromogenes 2, S. cohnii ssp. cohnii 1, S. delphini 1, S. epidermidis 6, S. gallinarum 1, S. haemolyticus 6, S. hominis 1, S. hyicus 4, S. intermedius 8, M. lentus 2, S. lugdunensis 1, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans 1, S, schleiferi ssp. schleiferi 1, S. warneri 1, S. xylosus 1, S. agalctiae 3, S. bovis 2, S. dysgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae 4, S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis 7, S. intestinalis 5, S. milleri 3, S. pyogenes 5, S. sanguinis 1, S. solitarus 1, S. uberis 2), Bitches (M luteus 1, S. aureus 1, S. haemolyticus 1, S. hyicus 1, S. lugdunenis 1), Goats (S. epidermidis 1, S. haemolyticus 1), Woman (S. pyogenes 1) |

| Bacteria other than enterobacteriaceae and Gram +ve cocci (21) | Buffaloes 6, Cows 12, dog 1, Goats 2 | Buffaloes (A. lwoffii 1, A. hydrophila 1, A. denitrificans 1, A. faecalis 1, B. subtilis 1, M. sciuri 2, P. aeruginosa 1), Cows (A. jandei 1, A. salmonicida spp. smithia 1, A. samonicida ssp. salmonicida 1, A. scubertii 1, A. denitrificans 2, A. faecalis 2, B. cereus 1, B. cepacia 1, M. sciuri 1, M. osloensis 1, P. amylyticus 1, P. macerens 1, P. canis 1, P. aeruginosa 3), Bitch (A. faecalis 1), Goats (A. calcoaceticus 1, A. bestiarum 1, A. caviae 1) |

| Staphylococcaceae (64) | Buffaloes 15, Cows 44, Bitches 3, Goats 2 | Buffaloes (M. sciuri 2, S. aureus 7, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 1, S. delphini 1, S. epidermidis 4, S. haemolyticus 2, S. kloosii 1, S. sacchrolyticus 1), Cows (M. lentus 2, M. sciuri 1, S. aureus 12, S. capitis ssp. capitis 1, S. capitis ssp. urealyticus 1, S. cparae 2, S. caseolyticus 2, S. chromogenes 2, S. cohnii ssp. cohnii 1, S. delphini 1, S. epidermidis 6, S. gallinarum 1, S. haemolyticus 6, S. hominis 1, S. hyicus 4, S. intermedius 8, S. lentus 2, S. lugdunensis 1, S. schleiferi ssp. coagulans 1, S, schleiferi ssp. schleiferi 1, S. warneri 1, S. xylosus 1), Bitches (S. aureus 1, S. haemolyticus 1, S.hyicus 1, S.lugdunenis 1), Goats (S.epidermidis 1, S.haemolyticus 1) |

| Streptococcaceae (44) | Buffaloes 13, Cows 30, Woman 1 | Buffaloes (S. agalactiae 2, S. anginosus 1, S. dusgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae 1, S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis 1, S. milleri 5, S. morbilorum 1, S. phocae 1, S. pneumoniae 1, S. pyogenes 2), Cows (S. agalctiae 3, S. bovis 2, S. dysgalactiae ssp. dysgalactiae 4, S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis 7, S. intestinalis 5, S. milleri 3, S. pyogenes 5, S. sanguinis 1, S. solitarus 1, S. uberis 2), Woman (S. pyogenes 1) |

Though vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) were detected from five samples each, staphylococci of other species resistant to vancomycin (VRS) and methicillin (MRS) were also detected in 14 and 10 samples, respectively (Tab. 4). Carbapenem-resistant bacteria were detected in 24 samples, belonging to both G +ve and G -ve groups, from 13 samples each. Overall, the best antimicrobial against bacteria isolated from milk of cases of mastitis was carvacrol (Tab. 5), an active ingredient of thyme oil, ajovan oil and oregano oil inhibiting ~95% of the isolates closely followed by another herbal antimicrobial cinnamaldehyde (present in cinnamon oil) inhibiting ~91% of bacterial isolates followed by tigecycline (~91%) and imipenem (90%). The most commonly used antibiotics in mastitis therapy ciprofloxacin (enrofloxacin), amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, and ampicillin failed to inhibit 30%, 33%, 34% and 39% of the bacterial isolates from mastitis cases, respectively.

A total of 63.09%, 47.95%, 33.75% and 11.67% of bacterial isolates had MDR, ESBL production, multiple herbal drug resistance (MHDR) and carbapenem drug resistance (CR), respectively (Tab. 6). This trend varied a little with the origin of bacterial isolates from mastitis cases in different species (Tab. 5) viz., on isolates from buffaloes carvacrol was the most effective (98.67%) followed by tigecycline (93.88%), cinnamaldehyde (92.31%), imipenem (86.08%) while the commonly recommended antibiotics for mastitis therapy inhibited ≤70% of the isolates, >20% were resistant to carbapenem drugs and ~66% had MDR; on bacterial isolates from cows also, carvacrol was the most effective (95/54%) antimicrobial followed by carbapenems (92.17%), tigecycline and cinnamaldehyde (89.61%), and 64.06% of the isolates had MDR. A shift in susceptibility of bacterial isolates was evident from cases of mastitis in bitches, goats and women showing 100% susceptibility to cinnamaldehyde, followed by carbapenems. Carvacrol was much less effective on bacterial isolates from bitches (62.5%) and goats (83.33%). The variation in susceptibility to herbal and conventional antimicrobials in bacteria was not only associated with their isolation source (Tab. 5) but also differed among different species of bacteria (Tab. 7, 8). Bacteria isolated from mastitis milk of buffaloes were significantly (p, <0>Escherichia coli isolates were significantly (p, <0>E. coli of buffalo origin were more often (p, <0>E. coli isolates from mastitis cases in cows. Isolates of staphylococci from buffaloes were more often (p, <0>Staphylococcus aureus isolates from buffalo cases were significantly (p, <0>Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from buffaloes were more often (p, <0>Escherichia coli strains causing mastitis were more often resistant to lemongrass oil, doxycycline, carbapenems (p, <0>K. pneumoniae. Isolates of S. milleri were very often (p, <0>E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), holy basil oil (than S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), LGO (than S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), thyme oil (than E. coli, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. intermedius and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), citral (than S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), guggul oil (than S. intermedius, S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), cinnamon oil (than E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius, S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), doxycycline (than K. pneumoniae, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, and S. intermedius), gentamicin (than E. coli, S. aureus, and S. intermedius), meropenem (than S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius, and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), imipenem (than K. pneumoniae, and S. intermedius), amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (than S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius, and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), azithromycin (than S. epidermidis, S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), cefotaxime and cefotaxime + clavulanic acid (than E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius, and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), ceftriaxone (than S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), cefoxitin (than S. haemolyticus and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), cefepime (than E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, S. haemolyticus, S. pyogenes, and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), lincomycin (than S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), piperacillin and piperacillin + tazobactam (than S. haemolyticus, S. intermedius, S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis), but more susceptible to erythromycin (than E. coli, and S. aureus) and cinnamaldehyde (than K. pneumoniae). Despite the more frequent occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in S. milleri isolates, none of the isolates produced ESBL.

Table 5: Antimicrobial susceptibility expressed in percent of bacteria from different sources

| Antimicrobials | Source of mastitis milk samples (number of isolates tested, samples, % of total samples) | Types of bacteria (number of isolates tested, samples, % of total samples) | ||||||

| Buffaloes (79, 33, 27.05) | Cows (217, 80, 65.57) | Bitches (8, 4, 3.28) | Goats (12, 4, 3.28) | Human (1, 1, 0.82) | Gram +ve bacteria (200,104,85.25) | Gram -ve bacteria (117,51,41.80) | All (317, 122,100) | |

| Ajowan oil | 88.57 | 87.91 | 87.50 | 91.67 | 100 | 86.39 | 91.35 | 88.28 |

| Carvacrol | 98.67 | 95.54 | 62.50 | 83.33 | 100 | 96.22 | 92.92 | 94.97 |

| Cinnamaldehyde | 92.31 | 89.44 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 86.67 | 97.98 | 90.91 |

| Cinnamon oil | 83.56 | 87.94 | 87.50 | 66.67 | 100 | 83.98 | 89.29 | 86.01 |

| Citral | 65.22 | 62.22 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 100 | 73.33 | 44.76 | 62.22 |

| Guggul oil | 32.00 | 42.86 | 33.33 | 20.00 | 100 | 54.29 | 10.81 | 39.25 |

| Holy basil oil | 63.01 | 67.68 | 75.00 | 66.67 | 0.00 | 69.06 | 62.16 | 66.44 |

| Lemongrass oil | 55.84 | 53.62 | 62.50 | 50.00 | 100 | 64.77 | 36.61 | 54.43 |

| Thyme oil | 91.30 | 88.95 | 62.50 | 91.67 | 100 | 91.19 | 85.44 | 88.93 |

| Amoxicillin+clavulanic acid | 62.67 | 67.46 | 50.00 | 83.33 | 100 | 73.82 | 54.39 | 66.56 |

| Amoxicillin | 45.33 | 44.50 | 37.50 | 75.00 | 100 | 58.12 | 25.44 | 45.90 |

| Ampicillin | 70.49 | 56.83 | 50.00 | 83.33 | 100 | 72.46 | 41.84 | 61.13 |

| Azithromycin | 72.00 | 66.13 | 40.00 | 100 | 0.00 | 70.59 | 62.26 | 68.25 |

| Aztreonam | 70.83 | 58.49 | 50.00 | 80.00 | NA | NA | 63.10 | 63.10 |

| Cefepime | 68.85 | 83.33 | 75.00 | 100 | 100 | 78.13 | 83.67 | 80.23 |

| Cefotaxime | 63.83 | 79.19 | 57.14 | 100 | 100 | 78.00 | 73.86 | 76.47 |

| Cefotaxime+clavulanic acid | 84.09 | 85.06 | 87.50 | 100 | 100 | 84.85 | 86.42 | 85.45 |

| Cefoxitin | 56.52 | 67.72 | 62.50 | 100 | 100 | 75.57 | 44.83 | 66.14 |

| Ceftriaxone | 67.14 | 78.33 | 71.43 | 91.67 | 100 | 77.11 | 74.04 | 75.93 |

| Chloramphenicol | 78.57 | 83.89 | 87.50 | 100 | 100 | 88.30 | 74.49 | 83.27 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 68.42 | 70.14 | 62.50 | 87.50 | 0.00 | 68.62 | 71.55 | 69.74 |

| Colistin | 54.55 | 61.11 | 66.67 | 100 | NA | NA | 61.06 | 61.06 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 62.50 | 65.48 | 42.86 | 81.82 | 0.00 | 69.27 | 56.88 | 64.58 |

| Doxycycline | 60.38 | 74.79 | 85.71 | 100 | 100 | 79.51 | 60.29 | 72.63 |

| Erythromycin | 47.54 | 55.76 | 28.57 | 58.33 | 100 | 74.70 | 8.75 | 53.25 |

| Gentamicin | 79.49 | 80.09 | 62.50 | 100 | 100 | 73.30 | 91.45 | 80.19 |

| Imipenem | 86.08 | 92.17 | 87.50 | 100 | 100 | 96.32 | 81.82 | 90.48 |

| Lincomycin | 41.38 | 48.54 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 0.00 | 58.56 | 14.71 | 48.28 |

| Meropenem | 79.75 | 92.17 | 87.50 | 91.67 | 100 | 89.73 | 82.30 | 86.49 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 71.62 | 73.27 | 87.50 | 72.73 | 0.00 | 80.53 | 59.43 | 72.97 |

| Piperacillin | 56.60 | 66.91 | 57.14 | 100 | 100 | 72.73 | 52.05 | 65.37 |

| Piperacillin+Tazobactam | 65.45 | 79.59 | 71.43 | 100 | 100 | 79.58 | 71.05 | 76.61 |

| Tetracycline | 59.15 | 73.20 | 75.00 | 100 | 100 | 77.78 | 58.25 | 70.67 |

| Tigecycline | 93.88 | 89.61 | 87.50 | 100 | 100 | 95.52 | 84.09 | 90.99 |

| Vancomycin | 68.97 | 72.90 | 60.00 | 100 | 100 | 73.15 | NA | 73.15 |

Table 6: Types of drug-resistant bacteria present (in percent) in milk samples from cases of

| Antimicrobials | Source of mastitis milk samples (number of isolates tested, number of samples) | |||||

| Buffaloes (79, 33) | Cows (217, 80) | Bitches (8, 4) | Goats (12, 4) | Human (1, 1) | All (317, 122) | |

| Multiple herbal antimicrobial drug resistant bacteria | 32.91 | 32.26 | 50.00 | 58.33 | 0.00 | 33.75 |

| Multiple antimicrobial drug resistant bacteria | 65.82 | 64.06 | 75.00 | 16.67 | 100 | 63.09 |

| Extended spectrum β-lactamase producing bacteria | 50.63 | 48.39 | 50.00 | 16.67 | 100 | 47.95 |

| Carbapenem resistant bacteria | 20.25 | 8.76 | 12.50 | 8.33 | 0.00 | 11.67 |

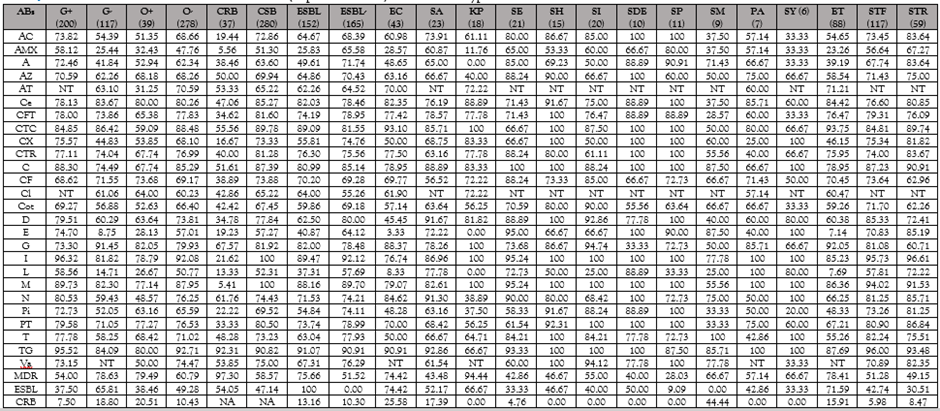

Table 7: Conventional antimicrobial resistance (expressed in %) in different types of bacteria isolated from cases of mastitis

Abs, antimicrobials; G+, Gram +ve; G-, Gram -ve; O+, Oxidase +ve; O-, Oxidase –ve; CRB , carbapenem-resistant bacteria; CSB, carbapenem-sensitive bacteria; ESBL, ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase; EC, Escherichia coli; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae ssp. pneumonia;, SE, Staphylococcus epidermidis;), SH, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; SI, Staphylococcus intermedius; SDE, Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis; SP, Streptococcus pyogenes; SM, Streptococcus milleri; PA, Pantoea agglomerans; SY, Staphylococcus hyicus; ET, Enterobacreiaceae; STF, Staphylococcaceae; STR, Streptococcaceae; NT, not tested, MDR. Multiple drug-resistant bacteria; AC, Amoxicillin +clavulanic acid; AMX, Amoxicillin; A, Ampicillin; AZ, Azithromycin; AT, Aztreonam; Ce, Cefepime; CFT, Cefotaxime; CTC, Cefotaxime+ clavulanic acid; CX, Cefoxitin; CTR, Ceftriaxone; C, Chloramphenicol; CF, Ciprofloxacin; Cl, Colistin; Cot, Cotrimoxazole; D, Doxycycline; E, Erythromycin; G, Gentamicin; I, Imipenem; L, Lincomycin; M, Meropenem; N, Nitrofurantoin; Pi, Piperacillin; PT, Piperacillin + Tazobactam; T, Tetracycline; TG, Tigecycline; Va, Vancomycin.

Table 8: Antimicrobial herbal drug resistance in important groups of bacteria isolated from cases of mastitis

| Groups of bacteria (isolates) | NIT | AEO | Car | CNH | CO | CTL | GO | HBO | LGO | TEO | MHDR |

| Gram +ve (200) | 104 | 86.39 | 96.22 | 86.67 | 83.98 | 73.33 | 54.29 | 69.06 | 64.77 | 91.19 | 24.00 |

| Gram -ve (117) | 51 | 91.35 | 92.92 | 97.98 | 89.29 | 44.76 | 10.81 | 62.16 | 36.61 | 85.44 | 50.43 |

| Oxidase +ve (39) | 14 | 75.76 | 83.33 | 100 | 88.89 | 69.44 | 29.17 | 72.22 | 60.53 | 77.14 | 33.33 |

| Oxidase -ve (278) | 118 | 90.00 | 96.56 | 89.57 | 85.60 | 61.11 | 40.53 | 65.63 | 53.56 | 90.75 | 33.81 |

| CRB (37) | 24 | 85.29 | 94.44 | 89.29 | 75.00 | 48.48 | 8.70 | 38.89 | 30.56 | 90.91 | 56.76 |

| CSB (280) | 115 | 88.70 | 95.04 | 91.10 | 87.55 | 64.14 | 42.93 | 70.31 | 57.62 | 88.65 | 30.71 |

| ESBL+ve (152) | 69 | 89.84 | 94.67 | 88.89 | 88.89 | 52.89 | 33.33 | 61.11 | 45.27 | 89.92 | 38.82 |

| ESBL-ve (165) | 85 | 86.90 | 95.27 | 92.52 | 83.22 | 69.80 | 44.95 | 71.62 | 63.06 | 88.11 | 29.09 |

| E. coli (43) | 29 | 97.30 | 100 | 100 | 82.50 | 27.78 | 6.25 | 53.85 | 21.43 | 88.57 | 60.47 |

| S. aureus (23) | 20 | 80.95 | 90.91 | 68.18 | 77.27 | 63.64 | 28.57 | 54.55 | 54.55 | 90.48 | 47.83 |

| K. pneumoniae (18) | 12 | 93.33 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 46.67 | 9.09 | 72.22 | 52.94 | 86.67 | 38.89 |

| S. epidermidis (21) | 11 | 78.95 | 85.00 | 73.68 | 73.68 | 63.16 | 42.11 | 47.37 | 55.00 | 89.47 | 42.86 |

| S. haemolyticus (15) | 10 | 100 | 93.33 | 90.91 | 86.67 | 72.73 | 50.00 | 80.00 | 80.00 | 90.00 | 20.00 |

| S. intermedius (20) | 8 | 90.00 | 100 | 93.75 | 90.00 | 81.25 | 85.71 | 70.00 | 80.00 | 93.75 | 10.00 |

| S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis (10) | 8 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 88.89 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.00 |

| S. pyogenes (11) | 8 | 87.50 | 100 | 87.50 | 87.50 | 75.00 | 72.73 | 75.00 | 63.64 | 85.71 | 77.78 |

| S. milleri (9) | 7 | 55.56 | 100 | 100 | 33.33 | 44.44 | 25.00 | 44.44 | 22.22 | 55.56 | 77.78 |

| P. agglomerans (7) | 6 | 85.71 | 100 | 85.71 | 100 | 57.14 | 0.00 | 71.43 | 50.00 | 85.71 | 28.57 |

| S. hyicus (6) | 5 | 100 | 100 | 80.00 | 40.00 | 80.00 | 33.33 | 100 | 83.33 | 100 | 16.67 |

| Enterobacreiaceae (88) | 46 | 94.94 | 97.67 | 97.30 | 89.41 | 39.74 | 8.77 | 60.71 | 33.33 | 88.31 | 51.14 |

| Gram +ve Cocci (191) | 99 | 87.04 | 96.05 | 85.99 | 83.24 | 73.89 | 53.62 | 69.94 | 65.22 | 91.39 | 24.08 |

| Other bacteria (38) | 21 | 78.13 | 82.86 | 100 | 91.43 | 60.00 | 26.32 | 62.86 | 48.65 | 79.41 | 42.11 |

| Staphylococcaceae (117) | 64 | 88.57 | 93.75 | 82.00 | 83.78 | 71.00 | 50.00 | 63.06 | 64.04 | 93.00 | 29.91 |

| Streptococcaceae (59) | 44 | 88.89 | 100 | 93.33 | 81.63 | 71.11 | 64.81 | 79.59 | 64.29 | 87.18 | 18.64 |

ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase; CRB, carbapenem-resistant bacteria; CSB, carbapenem-senitive bacteria; NPS, number of positive samples; AEO, Ajowan oil; Car, Carvacrol; CNH, Cinnamledehyde; CO, Cinnamon oil; CTL, Citral; GO, Guggul oil; HBO, Holy basil oil; LGO, Lemongrass oil; TEO, Thyme essential oil; MHDR, multiple herbal antimicrobial drug resistance; NIT, number of isolates tested.

Discussion

In the study of 122 samples of mastitis revealed that staphylococci (in 78, 63.93%), streptococci (in 48, 39.34%), E. coli in 29 (23.77%) and K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae (in12, 9.84%) were the most common causes of mastitis in bovine similar to earlier reports [4-13, 15, 16, 20, 21]. The study indicated that mastitis causes are almost similar across different species of hosts and in different environments too with some variation, and observations are in concurrence to earlier studies [4-13, 20-22]. This study indicated that bacterial causes of mastitis may be many but their occurrence may be different as many of the bacteria causing mastitis were missing from the bacteria identified in the present study. Thus, the diversity of bacterial causes of mastitis makes it mandatory to screen every case of clinical mastitis to keep an eye on the causes of mastitis. Though in most of the earlier studies S. aureus has been reported as the main cause of mastitis [4-13, 20-22], S. aureus was identified to cause only 16.39% of the cases as single cause while staphylococci belonging to other 20 species or subspecies were responsible for almost three times more number of mastitis cases (45.90%) in animals. Similar observations have been reported from other animals in countries too [18, 20, 21].

Only in 50% of the mastitis cases single types of bacteria was involved but in the other 50%, two to seven types of bacteria were detected indicating that the multiplicity of microbes (invaded either as secondary invaders or opportunistic pathogens) may be the cause of the poor response to mastitis management strategies adopted by livestock owners and veterinary practitioners [32, 33]. Therefore, antimicrobial susceptibility assays are recommended for clinical mastitis cases to institute an effective therapeutic intervention [24]. Antimicrobial susceptibility assays of bacteria from mastitis cases revealed that not only vancomycin Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was cause of mastitis but as many as in 24 cases carbapenem-resistant bacteria (CRB) were responsible. Though the emergence of MRSA as the cause of mastitis has frequently been reported [16], reports of VRSA and CRB are rare on record probably because carbapenems and vancomycin are not drugs of choice for mastitis treatment [9, 24]. The study indicated that the herbal antimicrobials and their active ingredients might be promising alternatives for the treatment of bacterial mastitis. Carvacrol, an active ingredient of thyme oil, ajowan oil and oregano oil inhibited ~95% of the bacterial isolates and cinnamaldehyde (present in cinnamon oil) inhibited ~91% of bacterial isolates associated with mastitis was better or as good as the tigecycline and imipenem, the last resort drugs permitted for therapeutic use. The use of herbal antimicrobials as antibiotic alternatives has been proposed time and again [9, 34] but the risk of emergence of resistance to herbal antimicrobials always exists [35] and their inherent irritant action prohibit for their clinical use [36]. Therefore, unless the in-vivo toxicity and counter-irritant problems of effective herbal antimicrobials are solved their use in therapeutics can’t be scaled. The most commonly used antibiotics in mastitis therapy [9, 24] ciprofloxacin (enrofloxacin), amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, and ampicillin were effective against 60-70% of the bacterial strains isolated from mastitis cases and use of such partially effective antimicrobial therapy may be one of the causes of poor response to treatment, further necessitating the routine antimicrobial susceptibility assays [24]. The utility of antimicrobial therapy was further jeopardised with the isolation of 63.09%, 47.95%, 33.75% and 11.67% of bacterial isolates having MDR, ESBL production, multiple herbal drug resistance and carbapenem drug resistance potential, respectively. The little and often insignificant variation in antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial isolates from mastitis samples of different host origins indicated the environmental risk of spreading MDR strains specifically when different animals are reared under an intensive system of animal husbandry [37]. Members of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from mastitis milk were significantly (p, ≤0.05) more often resistant than members of Staphylococcaceae and Streptococcaceae) to most of the herbal and conventional antimicrobials including those are the drug of choice for mastitis treatment [9, 24] and to antibiotics reserved for human therapeutics like imipenem, and tigecycline poses a public health risk due to their broad host range and easy transmutability through faeco-oral route and contaminated environment [37]. Among all streptococci isolated from mastitis milk S. milleri (S. anginosus) were more often (p, <0>S. dysgalactiae and S. pyogenes, the two most common causes of mastitis in bovines makes them emerging cause of mastitis of public health concern. In earlier studies on mastitis S. milleri has rarely been isolated but often reported as an important emerging pathogen causing septicaemia and other ailments like pyogenic infections, urinary tract and respiratory tract infections in animals and humans [38, 39].

Conclusion

The study concluded that mastitis may be caused by a large number of well-known and less-known and emerging bacteria having MDR necessitates for milk bacteriological culture for the institution of effective antimicrobial therapy for mastitis management.

Declarations

Funding

The research work was supported by grants received from CAAST-ACLH (NAHEP/CAAST/2018-19) of ICAR-World Bank-funded National Agricultural Higher Education Project (NAHEP).

Conflict of interest

None to declare

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted on clinical samples collected by the qualified veterinarians with the consent of the owner and approval from Animal Ethics Committee was not needed.

References

- Sinha MK, Thombare NN, Mondal B (2014). Subclinical mastitis in dairy animals: Incidence, economics, and predisposing factors. Sci World J.1–4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ruegg PL (2017). A 100-year review: mastitis detection, management, and prevention. J Dairy Sci. 100:10381–10397.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Barbuddhe S, Chakurkar E B (2008). Mastitis: Causes, prevention and control. Technical bulletin No: 12. Goa: ICAR Research Complex for Goa (Indian Council of Agricultural Research), Ela, Old Goa- 403 402, Goa, India.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW, Constable PD (2007). Veterinary medicine: a textbook of the disease of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs and goats. 10th ed. London: Elsevier.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bradley AJ, Green MJ (2002). Bovine mastitis: an evolving disease. Vet J. 164:116–128.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bhat AM, Soodan JS, Singh R et al. (2017). Incidence of bovine clinical mastitis in Jammu region and antibiogram of isolated pathogens. Vet World. 10(8):984-989.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ali T, Kamran, Raziq A, Wazir I et al. (2021). Prevalence of mastitis pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates from cattle and buffaloes in Northwest of Pakistan. Front Vet Sci.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cheng WN, Han SG (2020). Bovine mastitis: risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments - A review. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 33(11):1699-1713.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Belay N, Mohammed N, Seyoum W (2022). Bovine mastitis: Prevalence, risk factors, and bacterial pathogens isolated in lactating cows in Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia. Vet Med (Auckl). 7(13):9-19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gao J, Barkema HW, Zhang L et al. (2017). Incidence of clinical mastitis and distribution of pathogens on large Chinese dairy farms. J Dairy Sci. 100:4797–4806.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Iqbal M, Khan MA, Daraz B et al. (2004). Saddique U. Bacteriology of mastitic milk and in vitro antibiogram of the isolates. Pak Vet J. 24:161–164.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Krishnamoorthy P, Suresh KP, Saha S et al. (2017). Meta-analysis of prevalence of subclinical and clinical mastitis, major mastitis pathogens in dairy cattle in India. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 6(3):1214-1234.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Schukken YH, Hertl J, Bar D et al. (2009). Effects of repeated gram-positive and gram-negative clinical mastitis episodes on milk yield loss in Holstein dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 92:3091–3105.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Song X, Huang X, Xu H et al. (2020). The prevalence of pathogens causing bovine mastitis and their associated risk factors in 15 large dairy farms in China: An observational study. Vet Microbiol. 247:108757.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Blackmon MM, Nguyen H, Mukherji P (2023). Acute mastitis. In: StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Foxman B, D'Arcy H, Gillespie B et al. (2022). Lactation mastitis: occurrence and medical management among 946 breastfeeding women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 155(2):103-114.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pendergrass JA (2022). The Surprising signs of mastitis in dogs (and how to help your nursing dog feel better).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dosher KL (2009). Mastitis. In: Deborah C. Silverstein, Kate Hopper (Eds), small animal critical care medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vasiu I, Meroni G, Dąbrowski R et al. (2021). Aerobic isolates from gestational and non-gestational lactating bitches (Canis lupus familiaris). Animals (Basel). 14(11):3259.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mishra AK, Sharma N, Singh DD et al. (2018). Prevalence and bacterial etiology of subclinical mastitis in goats reared in organized farms. Vet World. 11(1):20-24.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jabbar A, Saleem MH, Iqbal MZ et al. (2020). Epidemiology and antibiogram of common mastitis-causing bacteria in Beetal goats. Vet World. 13(12):2596-2607.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kalogridou-Vassiliadou D (1991). Mastitis-related pathogens in goat milk. Small Ruminant Res. 4(2): 203-212.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Spencer JP (2008). Management of mastitis in breastfeeding women. Am Family Physician. 78(6):727-732.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Timonen A, Sammul M, Taponen S et al. (2021). Antimicrobial selection for the treatment of clinical mastitis and the efficacy of penicillin treatment protocols in large Estonian dairy herds. Antibiotics (Basel). 30(11):44.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Balemi A, Gumi B, Amenu K et al. (2021). Prevalence of mastitis and antibiotic resistance of bacterial isolates from cmt positive milk samples obtained from dairy cows, camels, and goats in two pastoral districts in Southern Ethiopia. Animals. 11(6):1530.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Carter GR (1975). Diagnostic procedures in veterinary microbiology, 2nd edn. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publishers.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (2005). Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, Volume 2: The Proteobacteria, Part B: The Gammaproteobacteria. New York: Bergey’s Manual Trust, Springer.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh BR (2009). Labtop for microbiology laboratory. Berlin: Lambert Academic Publishing, AG & Co.

Publisher | Google Scholor - CLSI (2015). Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria, M45, 3rd edn. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

Publisher | Google Scholor - CLSI (2017). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 27th edn. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh BR, Sinha DK, Agrawal RK,Thomas P (2020). Comparative sensitivity of Salmonella isolates from clinical infections in animals and birds to herbal and conventional antimicrobials. Pharmaceutica Analytica Acta. 3(1):1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ajose DJ, Oluwarinde BO, Abolarinwa TO et al. (2022). Combating bovine mastitis in the dairy sector in an era of antimicrobial resistance: ethno-veterinary medicinal option as a viable alternative approach. Front Vet Sci. 9:800322.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Morales-Ubaldo AL, Rivero-Perez N, Valladares-Carranza B et al. (2023). Bovine mastitis, a worldwide impact disease: Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and viable alternative approaches. Vet Anim Sci. 21:100306.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh BR, Yadav A, Sinha DK, Vinodh Kumar OR (2020). Potential of herbal antibacterials as an alternative to antibiotics for multiple drug resistant bacteria: An analysis. Res J Vet Sci. 13(1):1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vadhana P, Singh BR, Bhardwaj M et al. (2015). Emergence of herbal antimicrobial drug resistance in clinical bacterial isolates. Pharm Analy Acta. 6:434.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumar A, Singh BR, Prakash SNJ et al. (2024). Study of antimicrobial efficacy of garlic oil loaded ethosome against clinical microbial isolates of diverse origin. J Herb Med. 43:100884.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh BR (2011). Environmental health risks from integrated farming system (IFS). In: SR Garg (Ed). Environmental health: Human and animal risk mitigation. Lucknow: CBS publishers. Pp. 373-383.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jiang S, Li M, Fu T et al. (2020). Clinical characteristics of infections caused by Streptococcus anginosus group. Au Sci Rep. 10(1):9032.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh BR, Agri H, Karthikeyan R, Jayakumar V (2023). Common bacterial causes of septicaemia in animals and birds detected in heart blood samples of referred cases of mortality in Northern India. J Clin Med Img. 7(7):1-15.

Publisher | Google Scholor