Case Report

A Dual Beta Blocker and Calcium Channel Blocker Overdose in a Patient with Substance Abuse

1MD candidate. Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine. Dayton, OH, USA.

2Hospitalist. Premier Health Network. Dayton, OH, USA.

*Corresponding Author: Rebekah Lantz, Hospitalist. Premier Health Network. Dayton, OH, USA.

Citation: Sarah L. Pulliam, Lantz R. (2023). A Dual Beta Blocker and Calcium Channel Blocker Overdose in a Patient with Substance Abuse, Journal of BioMed Research and Reports, BRS Publishers. 2(3); DOI: 10.59657/2837-4681.brs.23.025

Copyright: © 2023 Rebekah Lantz, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: May 05, 2023 | Accepted: May 19, 2023 | Published: May 26, 2023

Abstract

Aim: Nearly 25% of hospital admissions have related adverse drug events with 6-7% of these related to beta blockers (BB) or calcium channel blockers (CCB).

Introduction: In some cases, patients do not report their noncompliance at home as well as their illicit substance use leading to worsened outcomes. We present a case of BB and CCB toxicity with concomitant substance abuse, its treatment and general outcome.

Case: A 49-year-old woman with history of diabetes mellitus, stroke, and hypertension presented with flu-like symptoms including fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and dysuria. She was admitted for treatment of urinary tract infection and possible left lower lobar pneumonia with guideline-directed antibiotic and IV fluids for acute kidney injury. She was elusive about her substance use history and endorsed compliance with her cardiac and other medications. Unfortunately, after administration of her morning medications, she had cardiac decline including hypotension and bradycardia with a subsequent hypoglycemia and left sided deficits leading to further investigation into her medication adherence and substance use history. History evolved that she was noncompliant with her high dose cardiac medications and a urine drug screen was positive for amphetamines, barbiturates, and nonprescription benzodiazepines.

Treatment: The patient’s shock was treated with resuscitative fluids, glucagon, and calcium infusion as well as a short round of vasopressor. She was transferred to a higher acuity center for large vessel occlusion at the distal portion of the left vertebral artery as seen on stroke imaging. Her blood and urine cultures ultimately grew extended spectrum beta lactamase bacteria, meanwhile her shock was deemed medication-induced hypovolemic shock with a depressed heart rate response given a normal transthoracic echocardiogram and quick resolution after reversal agent. Despite the severity and progression of the hospitalization the patient elected to leave against medical advice (AMA) prior to neurosurgical evaluation and completion of antibiotics. She has since been seen well in follow up by her outpatient provider.

Discussion: Cardiac medications are associated with adverse cardiac effects and should be prescribed carefully in patients with substance abuse. Further elucidation of substance abuse led to improved treatment outcomes in this patient with polysubstance and alcohol abuse.

Keywords: dual beta blocker; calcium channel; blocker overdose; patient; substance abuse

Introduction

Studies have demonstrated that nearly one in four hospital admissions are linked to drug toxicities and medication adverse events [1-2]. In 2016, cardiovascular drugs were the second leading cause of drug related deaths [3]. Given that widespread cardiovascular drug use has increased over the decades, consequently so have overdoses of these prescribed medications with most cases of overdosing as unintentional [4-5].

Two commonly prescribed classes of cardiovascular drugs include calcium channel blockers (CCB) and beta-blockers (BB) with approximately 6.28% of annual fatal substance exposures in the United States involving cardiovascular agents [6]. Episodes of toxicity are more prevalent with increasing polypharmacy [7-8]. Additionally, recreational substance use with underlying heart conditions results in worse outcomes for those who experience poisonings concomitant with these cardiovascular agents [9]. We present a case of a middle-aged woman with comorbidities, an elusive polysubstance abuse history and likely noncompliance with prescribed medications so that her doses were further increased, resulting in the scenario presented during a hospitalization encounter.

Case

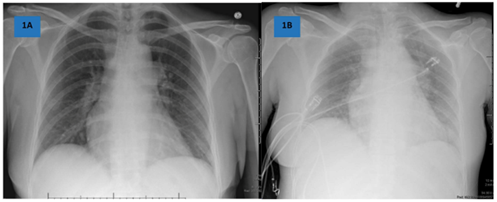

A 49-year-old woman with a medical history significant for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, right anterior cranial artery (ACA) ischemic stroke without residual deficits, polysubstance use, and alcoholism. Her home prescriptions included diltiazem, lisinopril, and atenolol. She was not taking an antiplatelet agent despite a stroke she endorsed “3 months ago” and chart history documented a stroke 13 months prior. Her complaints on presentation to the emergency department (ED) involved flu-like symptoms over the last 3 days including fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, urinary frequency, and dysuria. She subjectively felt similar to her previous stroke. Vital signs in the emergency department were nonacute with a temperature 98.1°F, pulse 94 bpm, blood pressure 144/85 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Her BMI 22 kg/m2. Additionally, her NIHSS was 0. Her serum labs were consistent with hyponatremia (129 mmol/L), acute kidney injury (AKI, creatinine 1.6 from baseline 0.8 mg/dL), hyperglycemia (173 mg/dL), acute on chronic thrombocytopenia (100K from baseline 122K). Procalcitonin was elevated at 1.48 ng/mL with a normal lactate. Her urine showed large leukocytes with >100 WBC/hpf and 4-7 clumps. AP chest x-ray suggested left lower lobar infiltrate Figure 1A, shown below with Figure 1B. Given history of stroke and similar subjective symptoms, head imaging was obtained and a head CT without contrast showed old infarct in the right ACA but was otherwise unremarkable.

Given urinalysis findings, the patient was diagnosed with urinary tract infection (UTI) and admitted to the low acuity medical floor. Urine and blood cultures were sent prior to guideline-directed antibiotic for both UTI and possible pneumonia with IV ceftriaxone. She was treated with IV isotonic saline for AKI and hyponatremia. Her low platelets were presumed related to acute infection and alcohol history. She did not exhibit signs of withdrawal and denied substance use in recent history and alcohol use within the past week. Given history of chronic stroke, aspirin monotherapy was initiated. Given stable blood pressures and reported adherence to home doses, she was continued on her home atenolol 50 mg and diltiazem 240 mg. Lisinopril was held due to AKI and she was started on low dose corrective scale insulin for hyperglycaemia.

Within a couple hours of receiving her morning medications, the patient developed bradycardia and hypotension. Besides moderate light headedness with walking, she was otherwise asymptomatic. She was given a small bolus of isotonic saline but surprisingly showed no improvement in vitals so was given a further 3L. A few hours thereafter, she was reported to be lethargic with focal left-sided neurologic symptoms. Motor was 3/5 for left upper and lower extremities without further findings resulting in NIHSS of 2 but these symptoms were improved and resolving 30 minutes later. At this time her vitals were 97.4°F, 75/58, pulse 52, respirations 20 and 95% saturations on room air. Stroke alert was initiated and she was transferred to a Level 1 Stroke center given abnormal neck imaging for neurosurgical evaluation.

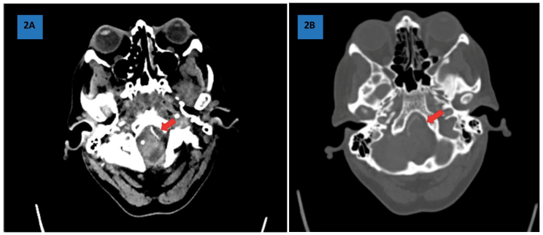

A head and neck CTA and CT cerebral perfusion studies showed large vessel occlusion (LVO) of the nondominant left cervical vertebral artery [Figure 2]. Repeat chest x-ray Figure 1B showed mild cardiomegaly with pulmonary vascular congestion. Her serum platelet count was lower at 80K/uL, haemoglobin was 10.5 from previous 11.9 g/dL, and calcium 7.4 from 8.6 mg/dL. Troponins were non trending and thyroid function studies were normal. Drug screen add-on was ultimately positive for amphetamines, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines.

Figure 1A: Admission PA chest X-ray with possible left basilar infiltrate.

Figure 1B: Hospital Day 2 PA chest X-ray showing signs of onset fluid overload.

Figure 2: CTA Head and Neck with CT Cerebral Perfusion Study showing occlusion of the distal portion of the nondominant left cervical vertebral artery with reconstitution of the intracranial segment and potential high-grade stenosis at the origin. Also, with chronic occlusion of the distal right ACA with adjacent known remote infarct.

The patient was not a candidate for tPA or endovascular treatment per the neurocritical care specialist given her resolving NIHSS. She was considered to have septic shock given UTI and decline but cultures were not resulted yet. Her antibiotic regimen was broadened to piperacillin/tazobactam. She did not have cold extremities or edema to diagnose cardiogenic shock. Ultimately, she was treated with only a couple hours of vasopressor after receiving reversal agents’ glucagon and calcium gluconate for BB and CCB respectively. Her transthoracic echocardiogram exhibited normal structure and function with mild right ventricular overload likely related to high volume fluid resuscitation. The patient immediately wanted to discharge home despite education that her blood cultures were growing antibiotic-resistant bacteria and concerns about further decline or death. She did not wait for further prescriptions or clinical advice and left against medical advice on Hospital Day 3.

She has since established care with a primary care provider, however continues to abuse alcohol and substances. She was last seen well and continues to be treated with difficult to control blood pressure related to medication noncompliance.

Discussion

Beta Blockers

BB are used to treat hypertension, heart failure, tachyarrhythmias, and angina and some off-label uses for anxiety, migraine, glaucoma, tremor, and hyperthyroidism. For cardio-selective options such as atenolol, bisoprolol, esmolol, and metoprolol, the mechanism involves antagonizing the beta-1 adrenergic receptor at the G-protein coupled receptor, decreasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and inhibiting long-lasting type (L-type) calcium channels from opening. This decreases contractility of the heart, heart rate, and cardiac output [10]. Non-selective beta blockers such as propranolol, labetalol, sotalol, and carvedilol antagonize the beta-2 adrenergic receptor also which results in vasodilation with a side effect of bronchodilation [11]. Notably the nonselective class of BB affects the beta agonist intention of asthma and obstructive lung disease prescriptions [12]. There are also third-generation BB, carvedilol and nebivolol, that release nitric oxide to further increase vasodilation and bronchodilation [13]. Notable in toxicity, BB are generally lipophilic and can pass through the blood-brain barrier [4].

Calcium Channel Blockers

CBB have two categories, dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine, that are used for hypertension, vasospasm, migraine, and supraventricular tachycardias. Dihydropyridines have a higher affinity to directly antagonize the long-lasting (L-type) calcium channels and include amlodipine, nifedipine, felodipine, and nicardipine. These drugs induce peripheral vascular smooth muscle relaxation, resulting in vasodilation [14]. Non-dihydropyridines have a higher affinity for transient type (T-type) calcium channels found in pacemaker cells and include verapamil and diltiazem [14-16]. Diltiazem is included in the subtype non-dihydropyridines benzothiazepine that is also used to treat CNS disorders among clothiapine and quetiapine and can also be used to treat headaches [17]. Due to doubling effects, dihydropyridines and non-dihydropyridines are absolutely contraindicated together and non-dihydropyridines are contraindicated in patients with heart failure [18].

Toxicity

While BB and CCB are commonly used to treat cardiovascular diagnoses, known symptoms of both are bradycardia and hypotension from decreased cardiac output and contractility. Also of note, hypoglycaemia typically follows due to L-type antagonism of the pancreatic islet cells by non-dihydropyridines and inhibition of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis by excess beta blockers [4-5]. Symptoms of overdose may include vomiting, altered mental status, respiratory distress, and arrhythmias [4-5]. Chronologically, serum concentrations of BB and CCB peak within 6 to 12 hours, however for slow-release formulations, it may take nearly 24 hours after ingestion for toxicity symptoms to begin. Once the toxic decline begins, decompensation may happen quickly, necessitating a thorough initial history from the patient [4-5,19].

Illicit Substances

Substance abuse is on the rise over the last decade and, like our patient, commonly abused substances include amphetamines, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines. In patients with acute amphetamine abuse, sinus tachycardia was common (43%), followed by prolonged QT (34%) however with normal echocardiography results (83%) [21]. Barbiturates as a common drug of abuse from the 1960s and 70s has been largely replaced by access to benzodiazepines. Variable use will affect BB metabolism, specifically after chronic barbiturate use if stopped abruptly and BB continued, there would be an amplified effect of BB concentration. Barbiturates have been associated with thrombocytopenia, hypotension, circulatory failure, cyanosis, respiratory depression, hyperthermia, seizures, and death [22]. Benzodiazepine overdose typically results in lethargy, ataxia, altered mental status, and respiratory compromise. It has also been associated with hypotension [23]. It was not believed that the patient took benzodiazepines during her hospital stay to result in the new neurologic findings and she did have a structural cause for changes. Also, she had refused to provide a new urine sample so that the sample obtained was an add-on from her admission urinalysis to assess for infectious source.

Treatment

For BB and CCB overdose, there is no gold standard treatment. Instead, it is recommended to use the patient’s hemodynamic stability and neurological status as a guide for treatment and consulting one’s local poison control center is often vital in treatment [4-5].

Most importantly airway-breathing-circulation (ABC) should be assessed followed by atropine in patients with symptomatic bradycardia and ensure intravenous (IV) access for further medications. If presenting early in toxicity, activated charcoal by mouth may be an option within six hours of ingestion for gastrointestinal decontamination. Hypotension should be managed with IV isotonic fluids and possibly vasopressor. IV calcium gluconate is the reversal agent of choice for CCB. Glucagon reverses hypoglycaemic effects of both BB and CCB and should be administered with IV dextrose. Arrhythmias may necessitate sodium bicarbonate and magnesium for cardiac stabilization [24-25].

Additionally, if vitals do not improve, extracorporeal dialysis was thought to be a solution for severe cases of BB or CCB toxicity, however, given their protein-bound nature, traditional dialysis was ultimately thought to not contribute to toxicity offloading. Single-pass albumin dialysis and molecular adsorbent recirculating systems are under investigation as a means to filter further protein-bound compounds [28].

Our patient fortunately improved with reversal agents’ glucagon and calcium gluconate although she did require a short period of vasopressors. Her history of stroke with LVO continued to be concerning with neurosurgical evaluation needed. Her continued use of substances continues to expose her to increased risk of stroke and other cardiovascular events.

Conclusion

A careful history is always recommended with patient admissions however may be limited by patient provided information, especially regarding medication compliance and substance abuse. Patients who experience decline during hospitalization warrant further investigation into further causes. Completed course of treatment may be difficult in these patients who continue to abuse substances. Careful monitoring of external substances taken during hospitalization may also be encouraged by providers and hospital staff.

References

- Bates DW, Levine DM, Salmasian H, et al. The Safety of Inpatient Health Care. NEJM, 388:142-153.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Southwick R. (2023). One in four hospital patients suffers adverse events, and some can be avoided. Chief Healthcare Executive.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cole JB, Arens AM. (2022). Cardiotoxic Medication Poisoning. Emerg Med Clin of N Amer, 40(2):395-416.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Khalid MM, Galuska MA, Hamilton RJ. (2023). Beta-Blocker Toxicity. Treasure Island (FL). StatPearls Publishing.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alshaya OA, Alhamed A, Althewaibi S, et al. (2022). Calcium Channel Blocker Toxicity: A Practical Approach. J Multidiscip Healthc., 15:1851-1862.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. (2017) Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NDPS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 55:1072-252.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B, et al. (2022). Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr, 22:601.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Parulekar MS, Rogers CK. (2018). Chapter 9: Polypharmacy and Mobility. In Cifu DX, Lew HL, Oh-Park M. Ger Rehab. Elsevier,:121-129.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Grubb AF, Greene SJ, Fudim M, et al. (2022). Drugs of Abuse and Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 27(11):1260-1275.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tucker WD, Sankar P, Kariyanna PT. (2023). Selective Beta-1-Blockers. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jacob D. (2023). How Do Nonselective beta Blockers Work? RxList.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chang CL, Mills GD, McLachlan JD, et al. (2023). Cardio-selective and non-selective beta-blockers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects on bronchodilator response and exercise. Intern Med J., 40(3):193-200.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hess ML, Varma A. (2013). The Third-Generation Beta-Blocker: Have We Found the Elusive, Effective Antioxidant? J Cardiovasc Pharmac., 62(5):443-444.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McKeever RG, Hamilton RJ. (2023). Calcium Channel Blockers. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. (2014). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 32(1):3-15.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Marks J. (2008). Definition of Calcium Channel Blocker. RxList.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bariwal JB, Upadhyay KD, Manvar AT, et al. (2008). 1,5-Benzothiazepine, a versatile pharmacophore: a review. Eur J Med Chem., 43(11):2279-2290.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Page RL, Cheng D, Dow TJ, et al. (2016). Drugs that may cause or exacerbate heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 134:e32-69.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jang DH, Spyres MB, Fox L, Manini AF. (2014). Toxin-induced cardiovascular failure. Emerg Med Clin North Am, 32(1):79-102.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dominic P, Ahmad J, Awwab H, et al. (2022). Stimulant Drugs of Abuse and Cardiac Arrhythmias. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 15:e010273.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bazmi E, Mousavi F, Giahchin L, et al. (2017). Cardiovascular Complications of Acute Amphetamine Abuse: Cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J., 17(1):e31-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Suddock JT, Cain MD. (2023). Barbiturate Toxicity. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kang M, Galuska MA, Ghassemzadeh S. (2023). Benzodiazepine Toxicity. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Barrueto F. (2023). Beta blocker poisoning.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Barrueto F. (2023). Calcium channel blocker poisoning.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elkhapery A, Boppana HK, Vallabhajosyula S, et al. (2022). Abstract 10437: Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Rescue Therapy in Vasoplegic Shock Due to Calcium Channel Blocker Overdose: 5 Year Single Center Experience. Circulation, 146(Supplement 1).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Wong A, Hoffman RS, Walsh SJ, et al. (2021). Extracorporeal treatment for calcium channel blocker poisoning: systematic review and recommendations from the EXTRIP workgroup. Clin Toxicol, 59(5):361-375.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Essink J, Berg S, Montange J, et al. (2022). Single-Pass Albumin Dialysis as Rescue Therapy for Pediatric Calcium Channel Blocker Overdose. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep., 10:23247096221105251.

Publisher | Google Scholor