Review Article

Varicella-Zoster Virus Disease Hepes Zoster- A Common Viral Infection of the Nerves

1Department of chemistry Sri JNMPG College Lucknow U.P, India.

2Department of chemistry Dayanand Girls PG College Kanpur U.P, India.

*Corresponding Author: D.K. Awasthi, Department of chemistry Sri JNMPG College Lucknow U.P, India.

Citation: Awasthi D.K, Dixit A. (2023). Varicella-Zoster Virus Disease Hepes Zoster- A common Viral Infection of the Nerves. Journal of Clinical Medicine and Practice, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 1(2):1-7. DOI: 10.59657/3065-5668.23.003

Copyright: © 2024 D.K. Awasthi, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: March 04, 2024 | Accepted: June 13, 2024 | Published: August 05, 2024

Abstract

Shingles is a painful, blistery rash in one specific area of your body. Most of us get chickenpox in our lives, usually when we are children. Shingles is a reactivation of that chickenpox virus but only in one nerve root. So instead of getting spots all over your body, as you do when you have chickenpox, you get them just in one area of your body. It is almost always just on one side of your body, although it may go right around from front to back, following the skin the nerve affects. The affected skin hurts, and it may start to hurt before the rash appears, and may keep hurting for some time after the rash has gone. You may feel generally off-color and not yourself. Shingles symptoms occur in the area of skin that is supplied by the affected nerve fibers. The usual symptoms are pain and a rash. Occasionally, two or three nerves next to each other are affected. Very rarely, shingles can cause more widespread infection, or can affect both sides of the body, but this is usually only in people with a weakened immune system. The most commonly involved nerves are those supplying the skin on the chest or tummy (abdomen). The upper face (including an eye) is also a common site.

Keywords: chickenpox; shingles; nerve fibre; immune system

Introduction

Details

Herpes zoster, or shingles, is a common viral infection of the nerves, which results in a painful rash of small blisters on a strip of skin anywhere on the body. Even after the rash is gone, the pain may continue for months.

- Shingles is relatively rare in children.

- Your child is most at risk if he had chicken pox during the first year of life or if you had chickenpox very late during pregnancy.

- A rash most often occurs on the trunk and buttocks, and usually goes away in one to two weeks.

- Medication may help alleviate some of the pain, but the disease has to run its course.

The rash associated with herpes zoster most often occurs on the trunk and buttocks. It may also appear on the arms, legs, or face. While symptoms may vary child to child, the most common include:

- skin hypersensitivity in the area where the herpes zoster is to appear.

- mild rash, which appears after five days and first looks like small, red spots that turn into blisters.

- blisters, which turn yellow and dry, often leaving small, pitted scars.

- rash goes away in one to two weeks.

- rash is usually localized to one side of the body.

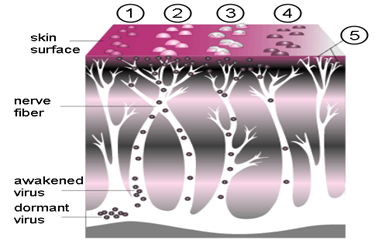

Figure: 1

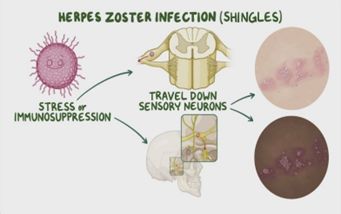

Herpes zoster is caused by the reactivation of the chickenpox virus. After a person has had chickenpox, the virus lies dormant in certain nerves for many years.

Herpes zoster is more common in people with a depressed immune system and those over the age of 50. It's quite rare in children, and the symptoms are mild compared to what an adult may experience. Children most at risk for herpes zoster are those who had chickenpox during the first year of life or whose mothers had chickenpox very late during pregnancy.

Figure: 2

Diagnosis usually involves obtaining a medical history of your child and performing a physical exam. Your doctor also may want to:

- take skin scrapings (gently scraping the blisters to determine if the virus is shingles or another virus)

- run blood tests

Shingles is a painful, blistery rash in one specific area of your body. Most of us get chickenpox in our lives, usually when we are children. Shingles is a reactivation of that chickenpox virus but only in one nerve root. So instead of getting spots all over your body, as you do when you have chickenpox, you get them just in one area of your body.

It is almost always just on one side of your body, although it may go right around from front to back, following the skin the nerve affects. The affected skin hurts, and it may start to hurt before the rash appears, and may keep hurting for some time after the rash has gone. You may feel generally off-color and not yourself. Shingles symptoms occur in the area of skin that is supplied by the affected nerve fibers. The usual symptoms are pain and a rash. Occasionally, two or three nerves next to each other are affected. Very rarely, shingles can cause more widespread infection, or can affect both sides of the body, but this is usually only in people with a weakened immune system. The most commonly involved nerves are those supplying the skin on the chest or tummy (abdomen). The upper face (including an eye) is also a common site.

Figure: 3

The shingles pain is a localized band of pain. It can be anywhere on your body, depending on which nerve is affected. The pain can range from mild to severe. You may have a constant dull, burning, or gnawing pain. In addition, or instead, you may have sharp and stabbing pains that come and go. The affected area of skin is usually tender.

The shingles rash typically appears 2-3 days after the pain begins. Red blotches appear that quickly develop into itchy fluid-filled blisters. The rash looks like chickenpox but only appears on the band of skin supplied by the affected nerve. New blisters may appear for up to a week. The soft tissues under and around the rash may become swollen for a while due to inflammation caused by the virus. The blisters then dry up, form scabs and gradually fade away. Slight scarring may occur where the blisters have been. The picture shows a scabbing rash (a few days old) of a fairly bad bout of shingles. In this person, it has affected a nerve and the skin that the nerve supplies, on the left side of the abdomen.

The shingles rash is contagious (for someone else to catch chickenpox) until all the blisters (vesicles) have scabbed and are dry. If the blisters are covered with a dressing, it is unlikely that the virus will pass on to others. This is because the virus is passed on by direct contact with the blisters.

Figure: 4

Shingles appears as red blotches, usually on your chest or stomach. These rashes develop into blisters filled with fluid and will only appear on one side of your body. If they appear on both sides of your body, it's not likely to be shingles causing the problem.

Shingles Day 2

Figure: 5

Shingles Day 6

Figure: 6

Shingles is an infection of a nerve and the area of skin supplied by the nerve. It is caused by a virus called the varicella-zoster virus. It is the same virus that causes chickenpox. Anyone who has had chickenpox in the past may develop shingles. Shingles is sometimes called herpes zoster. (Note: this is very different to genital herpes which is caused by a different virus called herpes simplex.)

About 1 in 4 people have shingles at some time in their lives. It can occur at any age but it is most common in older adults (over the age of 50 years). After the age of 50, it becomes increasingly more common as you get older. It is uncommon to have shingles more than once but some people do have it more than once.

Two main aims of treating shingles are:

- To ease any pain and discomfort during the episode of shingles.

- To prevent shingles, as much as possible, complications from developing.

General measures to alleviate shingles symptoms

Loose-fitting cotton clothes are best to reduce irritating the affected area of skin. Pain may be eased by cooling the affected area with ice cubes (wrapped in a plastic bag), wet dressings, or a cool bath. A non-adherent dressing that covers the rash when it is blistered and raw may help to reduce pain caused by contact with clothing. Simple creams (emollients) may be helpful if the rash is itchy. Calamine lotion can help to cool the skin and reduce mild itchiness.

Painkillers for shingles

paracetamol combined with codeine, (such asibrufen - may give some relief for shingles. Strong Pain killer (such as oxycodone and tramadol may be needed in some cases.

Some painkillers are particularly useful for nerve pain. If the pain during an episode of shingles is severe, or if you develop postherpetic neurology (PHN) you may be advised to take:

- An antidepressant medicine in the tricyclic group. An antidepressant is not used here to treat depression. Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, imipramine and notriptyline, ease nerve pain (neuralgia) separates to their action on depression; or

- An anticonvulsant medicine such as gabapentin or pregabalin They also ease neuralgic pain separate to their action to control convulsions.

If an antidepressant or anticonvulsant is advised, you should take it regularly as prescribed. It may take up to two or more weeks for it to become fully effective to ease pain. In addition to easing pain during an episode of shingles, they may also help to prevent PHN.

Antiviral medicines for shingles

Antiviral medicines used to treat shingles include acyclovir, famciclovir and valaciclovir An antiviral medicine is not a cure for shingles, it does not kill the virus but works by stopping the virus from multiplying. So, it may limit the severity of symptoms of the shingles episode.

An antiviral medicine is most useful when started in the early stages of shingles (within 72 hours of the rash appearing). However, in some cases your doctor may still advise you have an antiviral medicine even if the rash is more than 72 hours old - particularly in elderly people with severe shingles, or if shingles affects an eye.

Antiviral medicines are not advised routinely for everybody with shingles. As a general rule, the following groups of people who develop shingles will normally be advised to take an antiviral medicine:

- If you are over the age of 50. The older you are, the more risk there is of severe shingles or complications developing and the more likely you are to benefit from treatment.

- If you are of any age and have any of the following:

- Shingles that affects the eye or ear.

- A poorly functioning immune system (immunosuppression - see later for who is included).

- Shingles that affects any parts of the body apart from the trunk (that is, shingles affecting an arm, leg, neck, or genital area).

- Moderate or severe pain.

- Moderate or severe rash.

If prescribed, a course of an antiviral medicine normally lasts seven days.

Steroid medication for shingles

Steroids help to reduce swelling (inflammation). A short course ofsteroid tablets (prednisolone) may be considered in addition to antiviral medication. This may help to reduce pain and speed healing of the rash. However, the use of steroids in shingles is controversial.

Shingles and pregnancy

There's no danger to you or your baby if you catch shingles while pregnant. However, you may need antiviral treatment so you should be referred to a specialist.

If you have a poor immune system and develop shingles then see your doctor straightaway. You will normally be given antiviral medication whatever your age and will be monitored for complications. People with a poor immune system include:

- People taking high-dose steroids. (This means adults taking 40 mg prednisolone (steroid tablets) per day for more than one week in the previous three months. Or, children who have taken steroids within the previous three months, equivalent to prednisolone 2 mg/kg per day for at least one week, or 1 mg/kg per day for one month.)

- People on lower doses of steroids in combination with other immunosuppressant medicines.

- People taking anti-arthritis medications which can affect the bone marrow.

- People being treated with chemotherapy or generalised radiotherapy, or who have had these treatments within the previous six months.

- People who have had an organ transplant and are on immunosuppressive treatment.

- People who have had a bone marrow transplant and who are still immunosuppressed.

- People with an impaired immune system.

- People who are immunosuppressed with HIV infection.

Most people who get shingles do not have any complications. Those that sometimes occur include the following.

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN)

This is the most common complication of shingles. It is where the nerve pain (neuralgia) of shingles persists after the rash has gone.

Skin infection

Sometimes the rash becomes infected with germs (bacteria). The surrounding skin then becomes red and tender. If this occurs you may need a course of medicines called antibiotics.

Figure: 7

Eye problems

Shingles of the eye can cause inflammation of the front of the eye. In severe cases it can lead to inflammation of the whole of the eye which may cause vision loss.

Figure: 8

Weakness

Sometimes the nerve affected is a motor nerve (ones which control muscles) and not a usual sensory nerve (ones for touch). This may result in a weakness (palsy) of the muscles that are supplied by the nerve.

Various other rare complications

Examples are infection of the brain by the varicella-zoster virus, or spread of the virus throughout the body. These are very serious but rare. People with a poor immune system (immunosuppression) who develop shingles have a higher-than-normal risk of developing rare or serious complications.

Conclusion

Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)Disease

Herpes zoster manifests as a painful cutaneous eruption in a dermatomal distribution, often preceded by prodromal pain. The most common sites for herpes zoster are the thoracic dermatomes (40% to 50% of cases), followed by cranial nerve (20% to 25%), cervical (15% to 20%), lumbar (15%), and sacral (5%) dermatomes.16 Skin changes begin with an erythematous maculopapular rash, followed by the appearance of clear vesicles and accompanied by pain, which may be severe. New vesicle formation typically continues for 3 to 5 days, followed by lesion pustulation and scabbing. Crusts typically persist for 2 to 3 weeks. About 20% to 30% of people with HIV have one or more subsequent episodes of herpes zoster, which may involve the same or different dermatomes. The probability of a recurrence of herpes zoster within 1 year of the index episode is approximately 10%. Approximately 10% to 15% of people with HIV report post-herpetic neuralgia as a complication following herpes zoster.5,18When herpes zoster involves the nasociliary branch of the trigeminal nerve, the eye can be affected (herpes zoster ophthalmicus [HZO]), resulting in keratitis (inflammation of the cornea) or anterior uveitis (inflammation of the iris and anterior ciliary body) or both. Vesicles on the tip of the nose (Hutchinson sign) are a clue that the nasociliary branch is involved. With corneal involvement, there may be an initial brief period during which the corneal epithelium is infected with VZV, but the major problem is inflammation of the corneal stroma, which can result in scarring, neovascularization, or necrosis with loss of vision. Stromal keratitis can be chronic. Once it occurs, VZV-associated anterior uveitis also tends to be chronic and can result in increased intraocular pressure or glaucoma, scarring of intraocular tissues, and cataract. Stromal keratitis and anterior uveitis may not develop immediately after the appearance of skin vesicles on the forehead and scalp; therefore, patients with normal eye examinations initially should receive follow-up eye examinations, even after the skin lesions heal. Antiviral treatment of herpes zoster at the onset of cutaneous lesions reduces the incidence and severity of ophthalmic involvement.

References

- (2017). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About shingles.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dooling KL, Guo A, et al. (2018). Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 67:103-108.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Madkan V, Sra K, et al. (2018). Human herpes viruses. In: Bolognia JL, et al. Dermatology. (Second edition). Mosby Elsevier, Spain, 1204-1248.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Straus SE, Oxman MN. (2008). Varicella and herpes zoster. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine (seventh edition). McGraw Hill Medical, New York, :1885-1888.

Publisher | Google Scholor