Case Report

Right-Sided Infective Endocarditis with Myxoma

President of all nations, Morning star hospital, Enayam Thoppu, Kanyakumari District, India.

*Corresponding Author: Ramachandran Muthiah, President of all nations, Morning star hospital, Enayam Thoppu, Kanyakumari District, India.

Citation: Muthiah R. (2025). Right-Sided Infective Endocarditis with Myxoma, Clinical Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 4(1):1-18. DOI: 10.59657/2995-6064.brs.25.051

Copyright: © 2025 Ramachandran Muthiah, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 07, 2025 | Accepted: February 26, 2025 | Published: March 03, 2025

Abstract

Aim: To report a case of right ventricular myxoma prolapsing through the tricuspid valve with an attachment of vegetation in a 3-year-old male child.

Introduction: Right-sided endocarditis commonly involves the tricuspid valve. Low pressure and low oxygen saturation in the right sided cardiac chambers protect the tricuspid and pulmonary valves from being subjected to excessive strained and damage occurs from injected particulate matter, contaminated venous lines and drug solutions causing endocarditis. RV (right ventricular) myxoma harboured the infection due to trauma as a result of friction movement across the tricuspid valve.

Case Report: A 3-year-old male child having the spikes of fever for 2 weeks, presented with tumor “plop” and 3/6 systolic murmur in lower left sternal border and echocardiography revealed a tumor-mimicking vegetation visible as a mass lesion across the tricuspid valve, which is attached to the interventricular septum by a pedicle suggesting a RV myxoma. The vegetation was found to be attached with the tumor and it disappeared with antibiotics and aspirin therapy and the child was advised surgical removal of the tumor.

Conclusion: A diagnosis of infective endocarditis can be made in tricuspid valve dysfunction with a floating mass and fever. The tricuspid vegetations are often large and in rare instances, it may reach the size in excess of 20 mm [1]. The cardiac myxoma with attached vegetation masquerading as vegetation mass in this case on transthoracic echocardiography and the vast majority of patients in right-sided endocarditis respond to antimicrobial therapy and do not require surgery [2].

Keywords: RV myxoma; vegetation; tricuspid regurgitation; aspirin therapy; angiovac

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a microbial infection of the endocardial (endothelial) surface of the heart. It accounts for about 0.75 admissions per 1000 per year in large community hospitals [3] and a population-based incidence of 4-10 per 100,000 per year, with a slightly higher rate in men [4],[5]. Children with underlying cardiovascular disease may develop endocarditis at any age. It is most frequent on the left side of the heart [6]. Right-sided infective endocarditis is relatively rare, occurring in 5-10% of cases [7]. It involves the tricuspid valve in 90%, pulmonary valve in < 10>

Tricuspid valve infective endocarditis accounts for 2.5-3.1% of IE cases [11]. The right-sided infective endocarditis involving the right ventricular myxoma, prolapsing through tricuspid valve is uncommon and so this case had been reported.

Case Report

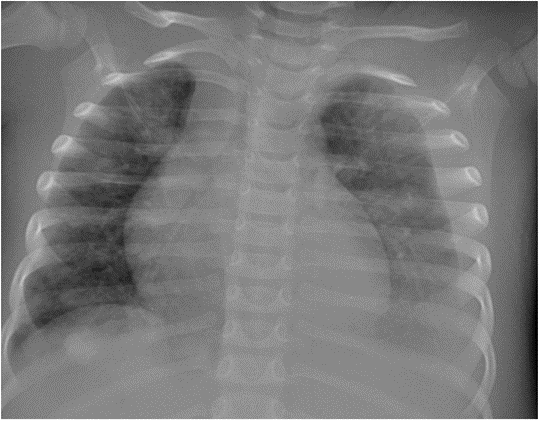

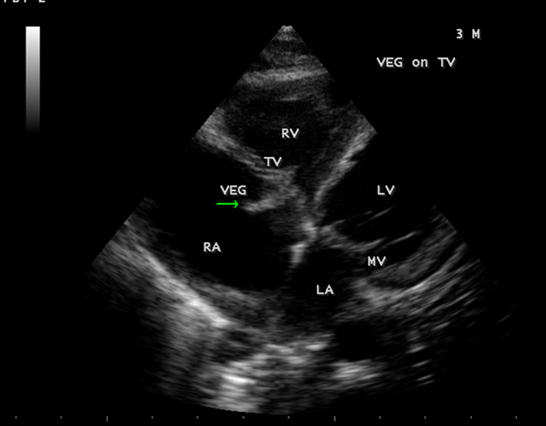

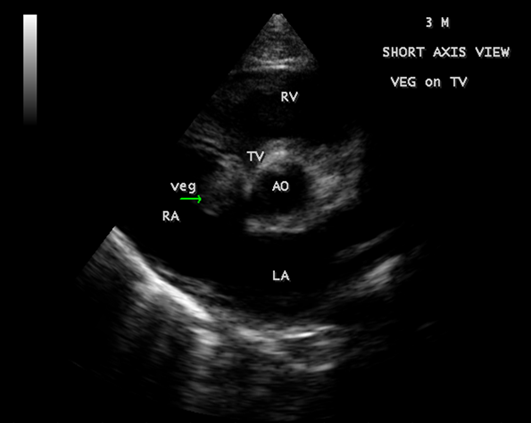

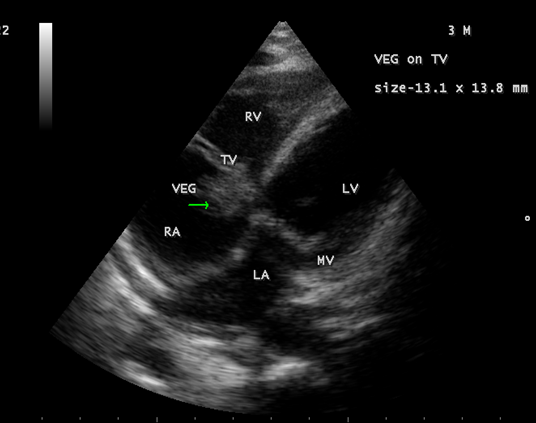

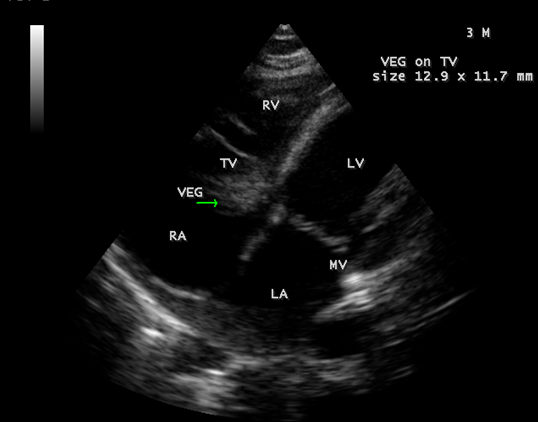

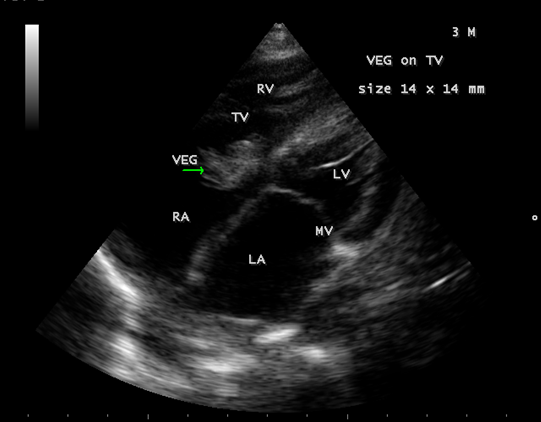

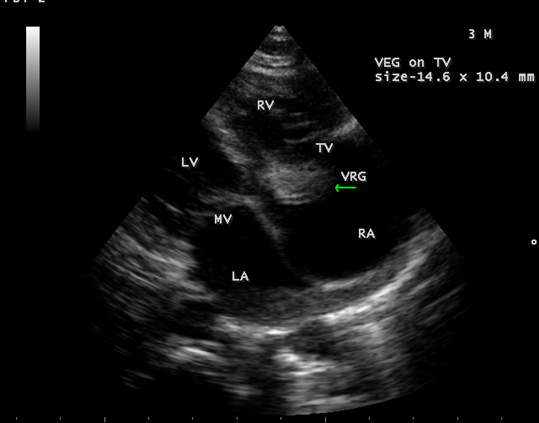

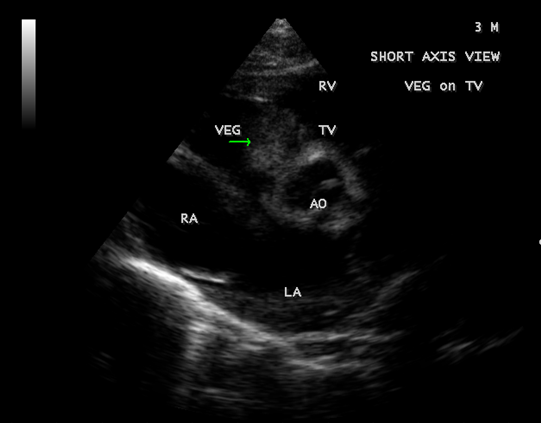

A 3-year-old male child with 2 weeks fever was referred for echocardiographic evaluation. His pulse rate was 112 bpm with a temperature elevation up to 101₀ F. Blood chemistry revealed leukocytosis with an elevation of total count up to 42700 cells/cubic mm of blood (normal- 4000 to 11000 cells/ cubic mm of blood) (Polymorphs -80% (normal-45 to 75%), Lymphocytes-17% (normal-25 to 40%), Eosinpphils-3% (normal-2 to 6%), Platelets-2.27 lakhs/cubic mm of blood. The child was mildly anemic- normochromic, normocytic red blood cell indices (Hb-7.7 gm % (normal-13.5 to 17 gm/dl). ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) was elevated-48 mm/hour (normal-0 to 20 mm/hr). Serum rheumatoid factor (RA factor) was negative (which may be detected in 50% of cases). Blood widal, Dengue antibody test, smear for malarial parasites and blood cultures were negative. Urinalysis revealed no microscopic hematuria. He had no other features of infective endocarditis such as Osler’s nodes, Janeway lesions, Roth spots, splinter hemorrhages which are relatively rare in children and no spotty skin pigmentation, a characteristic feature of myxoma in Carney complex. Abdominal examination revealed no splenomegaly (which occurs only in 10 to 15% of cases). ECG and X-ray chest PA (postero-anterior) were normal as shown in Figures 1 and 2. Physical examination revealed a grade 3/6 systolic murmur which increases with inspiration (Carvallo’s sign) and an early diastolic tumor “plop” due to abrupt diastolic seating of a mass in the right atrioventricular orifice [12] in the lower left sternal border on auscultation. 2D echocardiography revealed a large, mobile homogeneous mass in the tricuspid orifice, visible as a tumor-mimicking vegetation as shown in Figure 3-9.

Figure 1: ECG revealed a heart rate of 112 bpm due to fever.

Figure 2: X-ray chest PA (postero-anterior) view revealed normal.

Figure 3: Showing the vegetation prolapsing through the tricuspid valve in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 4: Short axis view showing the vegetation prolapsing through the tricuspid valve in a 3-year-old male child.

Figure 5: showing the tumor-mimicking vegetation in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 6: Showing the tumor-mimicking vegetation in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 7: Showing the tumor-mimicking vegetation in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 8: Subcostal view showing the tumor-mimicking vegetation in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 9: Short axis view showing the tumor-mimicking vegetation in a 3-year-old male child [13].

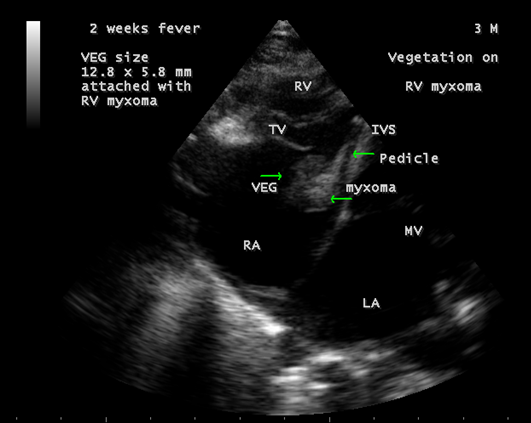

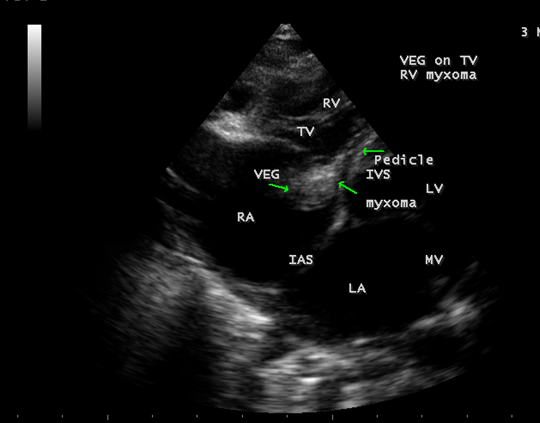

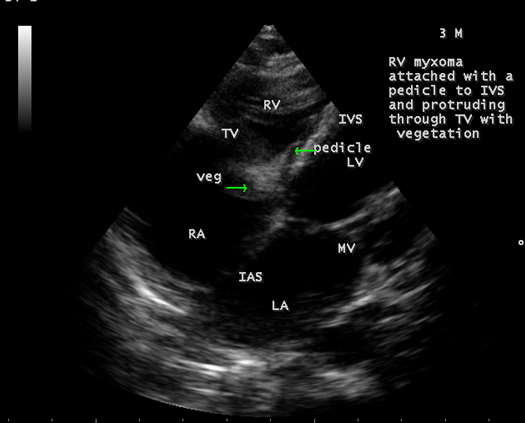

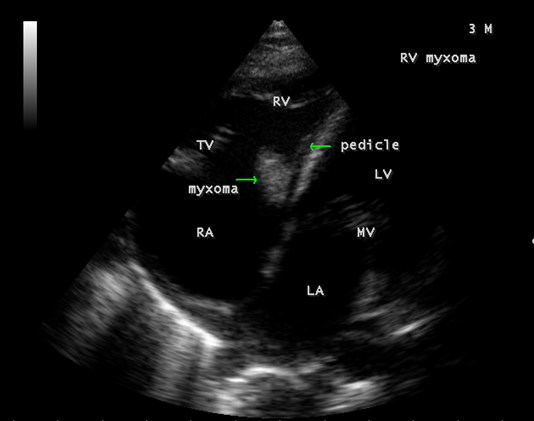

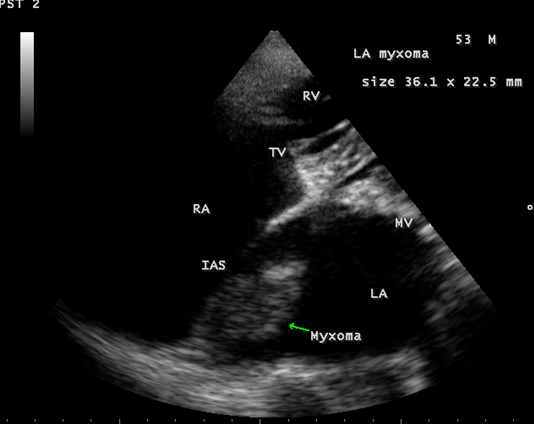

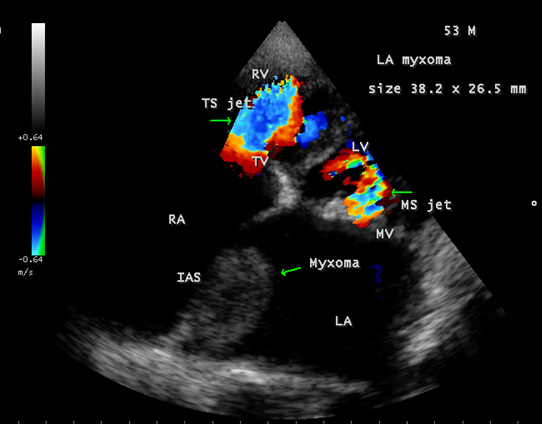

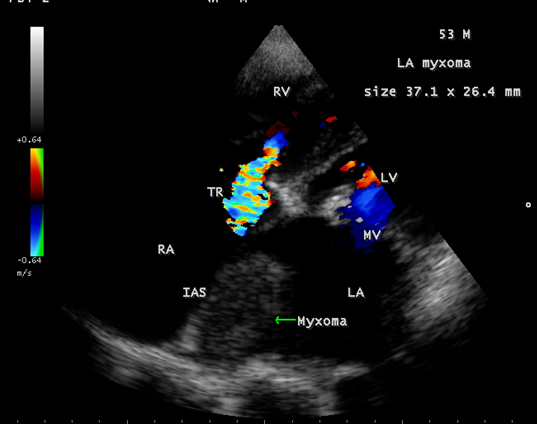

An irregular homogeneous hypodense mass suggesting a vegetation was attached to the mass, which is globular shape and a heterogeneous or mottled appearance throughout, with echolucent areas representing hemorrhage or necrosis suggesting a myxoma [14] as shown in Figures 10, 11 and 12.

Figure 10: Showing a vegetation attached to the myxoma in a 3-year-old male child.

Figure 11: Showing the myxoma with vegetation in a 3-year-old male child.

Figure 12: Showing the myxoma with vegetation in a 3-year-old male child.

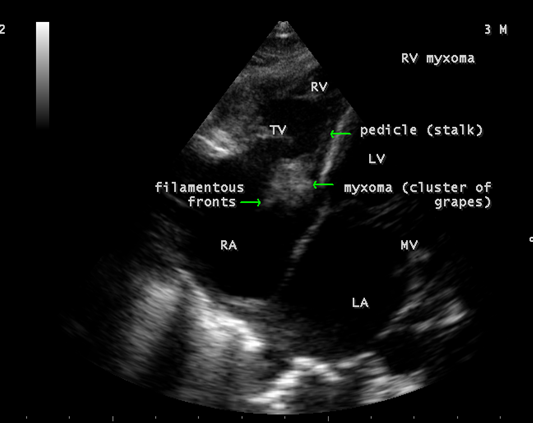

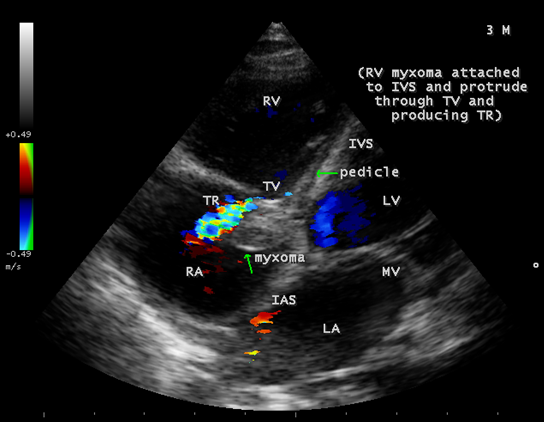

The mass was attached to the interventricular septum by a pedicle (stalk), protruding through the tricuspid valve and appear as “cluster of grapes” [15] as shown in Figures 13 and 14, suggesting a RV (right ventricular) myxoma.

Figure 13: Showing the RV (right ventricular myxoma) attached to the interventricular septum by a pedicle and appears as “cluster of grapes” with filamentous fronts in a 3-year-old male child.

Figure 14: Showing the RV (right ventricular myxoma) attached to the interventricular septum by a pedicle.

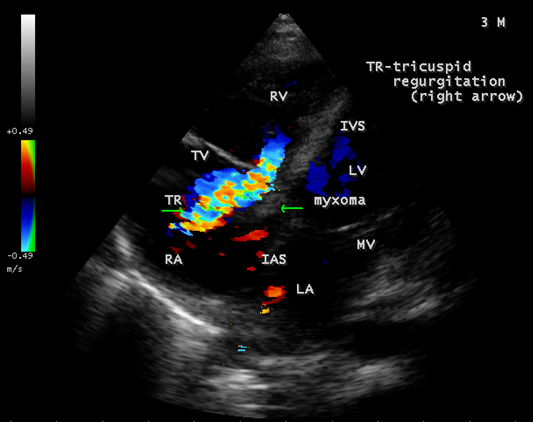

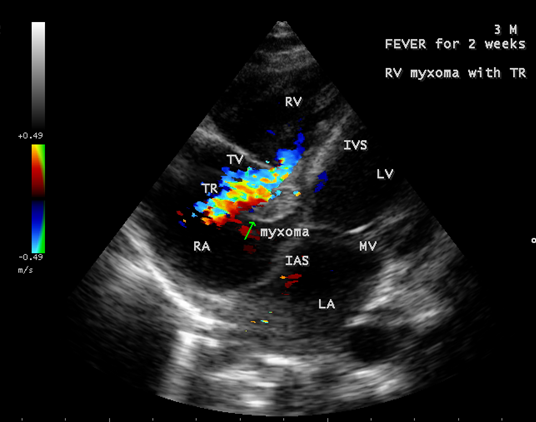

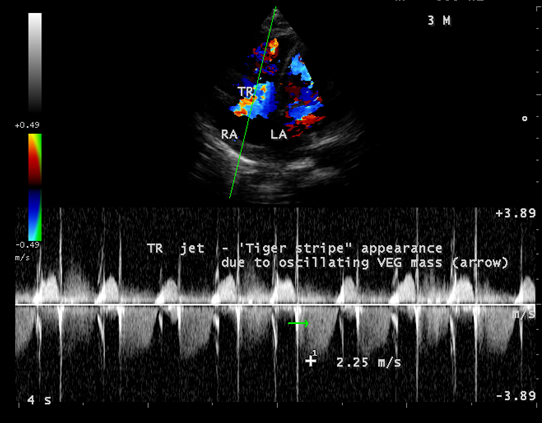

The mass, producing a traumatic regurgitation across the tricuspid valve due to friction movement as shown in Figures 15, 16 and 17.

Figure 15: Showing the severe tricuspid regurgitation with a mass lesion in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 16: Showing the moderate tricuspid regurgitation with a mass lesion in a 3-year-old male child

Figure 17: Spectral Doppler showing the ‘tiger-stripe’ appearance of the tricuspid regurgitant jet due to the oscillating mass across the valve.

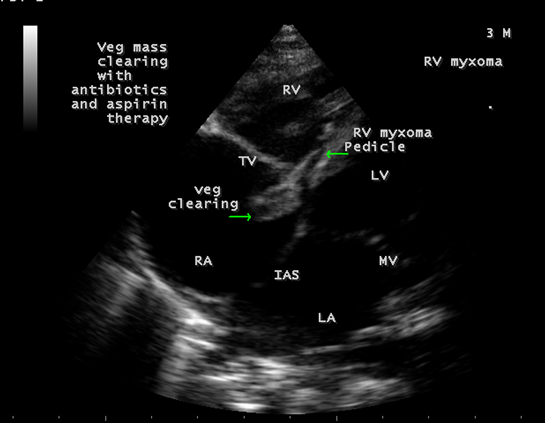

The child was treated with a course of intravenous ceftriaxone combined with gentamycin along with aspirin therapy for a period of 10 days, the tricuspid regurgitation decreases as in Figure 18 and the vegetation was found to be disappeared as shown in Figures 19. The child was advised periodic echocardiographic evaluation with a continuation of medications up to 4 weeks period and advised early surgical removal of the tumor.

Figure 18: Showing the mild tricuspid regurgitation with a mass lesion in a 3-year-old male child.

Figure 19: Showing the clearance of vegetation from the myxoma due to antibiotics and aspirin therapy.

Discussion

Review of literature

Lewis and Grant were the first to describe the infective endocarditis [16]. Gould, et al [17] found that bacteria most frequently responsible for endocarditis (e.g., viridans streptococci) displayed a propensity for adherence to human valves. There are only few reports of large tricuspid valve vegetations in the literature. Song, et al [18] reported a vegetation on tricuspid valve in a 33-year-old male, presented with right-sided heart failure and Furui, et al [19] reported a 1.5 cm vegetation on tricuspid valve in a 71-year-old male who developed ventricular septal perforation caused by right-sided infective endocarditis.

Etiopathogenesis

The endothelial lining of the heart and its valve is normally resistant to infection with bacteria and fungi. When there is a pressure gradient with resultant turbulence of blood flow, which against either the mural endocardium or vascular endothelium results in tissue damage due to high velocity jet (‘jet lesions’). Endocarditis begins as endothelial damage, followed by focal adherence of platelets and fibrin. The initial sterile platelet-fibrin nidus, first recognized by Angrist [20] and called as ‘nonbacterial thrombus’, then becomes infected by microorganisms circulating in the blood stream. Platelet-fibrin nidus involves a complex interaction of the components of microbial cell wall such as dextran in the cell wall of gram-positive organisms and valvular endothelium [21], intrinsic binding affinity to fibronectin [22] and glucosyl transferases which may act as “modulins” to express various cytokines (interleukin-6) or adhesions that in turn further recruit leukocytes into the vegetation [23]. The other factors which mediate adherence include fibrinogen, laminin, type 4 collagen which are the components found in the damaged endothelium or platelet-fibrin aggregate. Following colonization of platelet-fibrin aggregate [24], microbial growth results in the secondary accumulation of platelets and fibrin to form a vegetation. It consists of bacteria encashed in a meshwork of platelets and fibrin, serves as a barrier to host defences and it is not vascularized.

The propensity for vegetation to form at specific sites may also relate to a decrease in lateral pressure downstream from the regurgitant flow, which causes a decrease in the perfusion of intimal lining at these sites [25]. Tricuspid vegetations are large due to the low pressure in right heart chambers, allowing them to grow and may be in excess of 2 cm [26]. Vegetation often prevent proper valvular leaflet or cusp coaptation, thereby causing valvular incompetence resulting in congestive heart failure [27] or leaflet perforation secondary to vegetation growth [28] with recruitment of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and eventually destroy the collagen. Pneumonia or septic pulmonary embolism resulting from dislodgement of vegetative material are common. Recurrent pulmonary events, anemia and microscopic hematuria, the so called “tricuspid syndrome” is a feature of right-sided tricuspid valve endocarditis [29]. Tricuspid valve endocarditis may occur in community –acquired or hospital acquired infection and the organisms responsible for both are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: showing the organisms responsible for infective endocarditis. MRSA - methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus.

| Organism | Community acquired endocarditis (IV drug users) | Hospital acquirefd endocarditis (intravascular devices) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 30-50 % (MRSA-minority) | 60-80 % (MRSA-majority) |

| Α-hemolytic streptococci (viridians) | 10-35 % | less than 5 % |

| Enterococcus | 5-10 % | 5 % |

| Fungi | less than 5 % | 10 % |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (coagulase negative) | less than 5 % | les than 5 % |

| Others (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Corynebacterium) | less than 5 % | 5-10 % |

Cardiac myxomas are seen initially with protean manifestations that mimic many disease processes. About 5% of myxomas are found in the ventricles, usually solitary and attached to the interventricular serptum by a pedicle [30]. Small myxomas are silent and manifest if they become infected or embolize. The systemic manifestations consist of fever, weight loss, malaise, with leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, elevated ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), increase in gamma globulins, polycythemia and Raynaud’s phenomenon [31] may occur in 90% of myxomas.

Echocardiographic features

The most common and direct evidence of infective endocarditis is the vegetation and it must be at least 3 to 6 mm in size to be reliably seen. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) can, at best, detect vegetation to a minimum size of 2 mm and it is usually the more sensitive technique, with sensitivities in children up to 80% [32]. The characteristic echo appearance of a vegetation is of an echogenic mass, irregular in shape, attached to the ‘upstream’ side of a valve leaflet, i.e, atrial side of atrioventricular valves, most commonly at the coaptation line and prolapsed through the tricuspid valve as shown in Figures 3 and 4. The vegetation vary in size, sometimes reaching 2-3 cm in diameter and can be so big that they are mistaken for a cardiac tumor as shown in Figures 5 to 9. The gold standard for diagnosis of infective endocarditis is the modified Duke criteria [33] and it emphasized the essential relationship between clinical and echocardiographic findings. Duke’s criteria have been predominantly applied for left-sided endocarditis and have not been studied specifically in tricuspid valve endocarditis [34] and it may be difficult to determine [35] in its diagnosis.

Echocardiography remains the most safe and simple noninvasive method to diagnose the presence of an intracavitary myxoma [36]. Myxomas are typically non-homogeneos in texture with lucent centers or areas of calcification. They may be smooth surfaced but are more often irregularly shaped with filamentous fronts or have the appearance of “cluster of grapes” as shown in Figures 13 and 14. They are either sessile or pedunculated with a distinct stalk (pedicle), variably friable and originates from subendocardial nests of primitive mesenchymal cells. The tumor arising from the ventricular cavity was attached by a stalk to the interventricular septum as shown in Figures 10 to 14. Vegetation can occur on any surface [37]. Endocarditis usually begins as a mechanical traumatic event during the protrusion of myxoma through the tricuspid valve and the vegetations are attached to its surface as shown in Figures 10 to 12. The tumor mass is seen to oscillate into the right atrium through the tricuspid valve and producing regurgitation as shown in Figures 15 and 16 and the oscillations visible as ‘tiger-stripe’ appearance in the Spectral Doppler imaging as shown in Figure 17.

Management

Medical therapy

Fever, multiple pulmonary emboli and sustained bacteremia by staphylococcus aureus are the signs of clinical alert for right-sided endocarditis [38]. After the diagnosis of tricuspid valve endocarditis, medical treatment with antibiotics is indicated and should be continued for 4 to 6 weeks until the signs of infection disappear. Prolonged therapy is necessary since very high densities of bacteria approaching 109 to 1010 organisms per gram of tissue, become metabolically dormant and are difficult to eradicate since the organisms are relatively protected within the vegetation from phagocytic and other host defence mechanisms. Bactericidal antibiotics or antibiotic combination rather than bacteriostatic agents with high serum concentration may reach the central area of avascular vegetation by passive diffusion [39]. In small children, intravenous antibiotics with the use of heparin lock devices are preferred and home intravenous therapy is generally not recommended. Uncomplicated tricuspid valve endocarditis is successfully treated medically in 80% of cases. Given the low likelihood of adherence to 4–6-week therapy, shorter courses of therapy with a combination of β-lactam with or without an aminoglycoside (for 2 weeks) have become an accepted standard in methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus native valve endocarditis. Experience with 2 weeks regimen in children is limited, but it appears promising [40]. Short course therapy should not be used for patients infected with a relatively penicillin – resistant organisms, nutritionally deficient streptococcus and a presence of vegetation visible by echocardiography.

Unless the clinical or epidemiologic clues suggest an etiological diagnosis, the recommended treatment for culture-negative native valve endocarditis is ampicillin plus gentamycin. Ceftriaxone can be used in this regimen instead of ampicillin. Isolated native non-rheumatic fungal tricuspid valve endocarditis with a large and more friable vegetation is the most severe form of endocarditis. Aspergillus species (mostly Aspergillus fumigatus) are the second most common fungi isolated from cardiac vegetation (25%), whilst Candida accounts for 53% and Histoplasma for 6% of cases of fungal endocarditis. Amphotericin B has been the ‘gold standard’ treatment for Aspergillus endocarditis, despite its known poor penetration into vegetation [41]. The role of new echinocandins such as caspofungin has been recently approved and a combination of voriconazole with caspofungin is an alternative approach with promising results in refractory Aspergillus infection [42].

Aspirin therapy

Bacteria-platelet interaction appears to be important in both the induction of a vegetation and its enlargement after colonization. Acetylsalicylic acid was shown to have an effect on both platelets and organisms in a rabbit model of staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Animals treated with aspirin had reduction in the weight of valvular vegetation, its growth, density of bacteria and a decrease in embolic events compared to controls [43].

Surgical therapy

Although tricuspid valve endocarditis is successfully treated medically in about 75% of patients, conservative treatment is not always effective, and surgical treatment is required in approximately the remaining 25% [44,45]. The indications of surgery in right-sided infective endocarditis are not well defined, but it should be considered in the following circumstances as shown in Table 2 [46].

Table 2: Indications of surgery in right-sided infective endocarditis.

| Indications of surgery in right-sided infective endocarditis |

| TV (tricuspid valve) vegetation > 20 mm and recurrent septic pulmonary embolism with or without concomitant right heart failure |

| IE (infective endocarditis) caused by microorganisms that are difficult to eradicate (e.g. fungi) or bacteremia for at least 7 days (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) despite adequate antimicrobial therapy |

| Right heart failure secondary to severe tricuspid regurgitation with poor response to diuretic therapy. |

Timing of surgery in right-sided infective endocarditis is less clear. The optimum timing for the surgery was also stated previously [47]. The ESC (European Society of Cardiology) guidelines classified surgical indications in infective endocarditis as emergent (within 24 hours), urgent (within a few days), and elective (after 1 to 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy). The AHA/ACC guidelines define early surgery as occurring during the initial hospitalization and before completion of a full therapeutic course of antibiotics. Early surgery of tricuspid valve infective endocarditis is considered if there is infected indwelling catheters or pacing leads and a dehiscence of prosthetic valve due to perivalvular infection (unstable prostheses) [48]. Vegetation size is a questionable indication for surgery and a study by Lutas, et al [49] showed that the size of vegetation is not an indication for surgery by itself. According to the current guidelines, patients with large vegetation (> 15 mm) should be operated [50,51] on urgently (within days) and those with fungal infection that are resistant to medical treatment should be operated during the hospitalization period.

Tricuspid valve infective endocarditis can be especially perilous because the proliferation of growth called vegetation, may cause the valve to regurgitate. After the infection causes structural damage to the valve, antibiotics alone cannot cure and require surgery to stem the “snowball effect” the leaking valve [52]. The principles of surgery include radical debridement of vegetation/infected tissue and valve repair using a variety of techniques [53,54] such as autologous pericardial patch augmentation of the destroyed leaflets, implantation of an annuloplasty ring and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene neochord whenever possible. If the damage is too severe, the valve should be excised and replaced with a bovine pericardial valve, a bioprothesis preferably since there is a high risk of thrombosis due to low velocity of blood flow in right-sided chambers. The complete excision of the tricuspid valve was first described by Arbulu, et al [55] and valvectomy accounts for 7.2% of operations performed for tricuspid valve endocarditis in North America [56]. TV (tricuspid valve) excision should be limited to extreme cases only when the pulmonary artery pressure and vascular resistance are not elevated. Subsequent valve replacement should be considered once the infection is resolved. Fungal endocarditis remains a ‘stand-alone’ indication for surgical replacement of an infected valve. Tricuspid valve replacement resulted heart block in 16% of cases and epicardial lead placement should be considered since the placement of permanent endocardial leads across a bioprosthesis may cause regurgitation and reduces the prosthesis durability due to leaflet fibrosis and retraction. Prompt surgical removal of the intracardiac tumor is mandatory as systemic emboli or valvular obstruction can occur unexpectedly. The first surgical excision of a myxoma was performed in 1954 [57]. The myxoma is removed en bloc with its attachment to the interventricular septum [58] and every effort should be made to avoid fragmentation and embolization. Laser photocoagulation of a 1-cm area around the stalk attachment site has also been suggested as a way of eradicating pretumorous cells [59].

Interventional therapy

Surgical management of acute infective endocarditis is a major challenge. AngioVac [60], a suction thrombectomy device approved for removal of undesirable intravascular material, such as clots, tumors, or any foreign material in the vascular system. It can be an option in the management of right-sided infective endocarditis in critically ill patients with high surgical risk. Debulking the infection site and achieving lower bacterial load can increase antibiotic efficacy. Percutaneous vegetation removal has been used as a bridge to surgery in acute tricuspid valve endocarditis [61,62].

Outcome

The long-term prognosis of patients with negative blood culture infective endocarditis has been found to be similar to that of patients with positive blood culture infective endocarditis across all age groups [63]. Tricuspid valve infective endocarditis has a benign prognosis and an in-hospital mortality of < 10>15 mm [68] and, > 20 mm and fungal etiology [69] are the predictors of increase in mortality rate. Right-sided heart failure is also a predictor of poor outcome in right-sided endocarditis [70,71]. Numerous reports documented complete cure of myxoma with follow-up period of 10 to 15 years [72, 73] and the surgical results are excellent with resolution of associated symptoms [74]. In about 1 to 5 % of cases, a recurrence or secondary cardiac myxoma has been reported after resection of the initial tumor [75,76].

Case Analysis

A 3-year-old febrile male child despite antibiotic treatment for 2 weeks with an auscultatory findings of a right –sided regurgitant lesion as evidenced by grade 3/6 systolic murmur and a mass lesion as evidenced by tumor “plop” in lower left sternal border, suggesting a right-sided infective endocarditis of acute onset clinically. The non-drug users are generally present with symptoms of > 2 weeks duration [77] and if tricuspid valve is involved, heart murmurs are found with variable frequency in 35 to 72% of cases [78]. The source of infection is from in-situ intravenous canulas and the blood cultures are negative due to prior antibiotic therapy. Elevated total leukocyte counts up to 42,700 cells/cubic mm of blood is due to leukemoid reaction as the result of infection. The mass lesion can be confused as valvular vegetation by echocardiography as shown in Figures 5 to 9. The vegetation is adherent to the mass, which is attached to the interventricular septum by a pedicle suggesting the RV (right ventricular) myxoma as in Figures 10 to 14 and it is masquerading as tricuspid valve vegetation in figures 5 to 9. The infective process and trauma due to mass lesion results in significant valve damage and producing moderate to severe tricuspid regurgitation as shown in Figures 15 to 17.

Right-sided endocarditis, often allows time for medical treatment to take effect because the regurgitant lesion is well tolerated. Hence, it is recommended to treat medically with antibiotics initially before sending the patient for surgery. With effective treatment, regurgitant lesion decreased as in Figure 18, the vegetation gradually shrinks and disappeared as shown in Figure 19 even though disappearance of a vegetation should raise a suspicion that the vegetation has broken free and embolized elsewhere, but there were no signs of septic pulmonary emboli since the X-ray chest PA view revealed normal as in Figure 2. Because there is a high risk of relapse after short-term antibiotic therapy, prolonged therapy is recommended for a minimum period of 4 weeks [79] with an advice of surgical removal of tumor in this child.

Screening of population

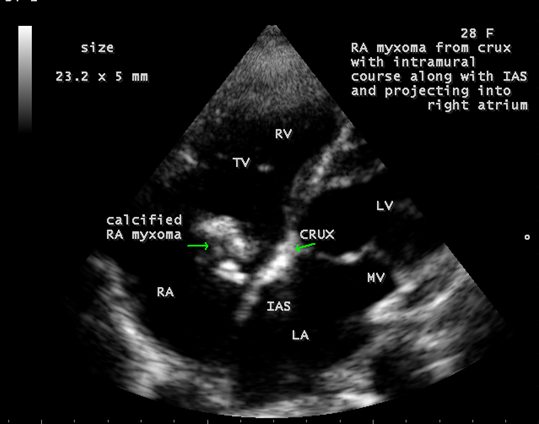

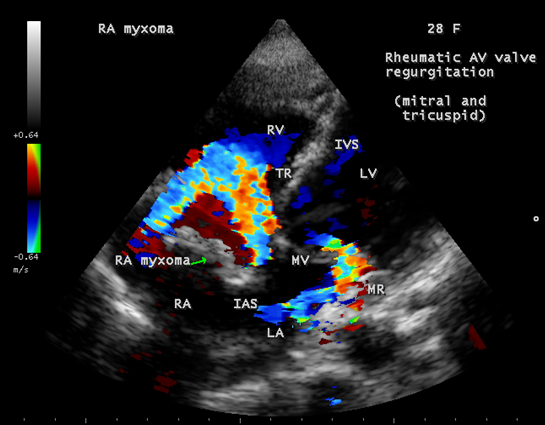

Calcification is present approximately in 10 to 20% of cardiac myxomas and right atrial myxomas appear to calcify more readily than left atrial myxoma [80] as shown in Figure 20 and it is associated with rheumatic AV valve (mitral and tricuspid) regurgitation as in Figure 21 in a 28-year-old male. A left atrial myxoma, attached to fossa ovalis, is associated with rheumatic AV valve stenosis (mitral and tricuspid) and tricuspid regurgitation as shown in Figures 22, 23 and 24 (Note: Thrombus typically produce a ‘layered appearance’ and is generally situated in the posterior portion of the atrium).

Figure 20: Showing the calcified right atrial myxoma in a 28-year-old male.

Figure 21: Showing the rheumatic AV valve (mitral and tricuspid) regurgitation associated with calcified right atrial myxoma in a 28-year-old male.

Figure 22: Showing the left atrial myxoma arising from the fossa ovalis of the interatrial septum in a 53 –year old male

Figure 23: Showing the left atrial myxoma associated with rheumatic AV valve stenosis (mitral and tricuspid) in a 53 –year old male.

Figure 24: Showing the left atrial myxoma associated with rheumatic tricuspid regurgitation in a 53-year-old male.

Conclusion

Right-sided endocarditis is generally considered to have a better prognosis and the initial approach to the treatment is conservative with antibiotics according to ESC (European Society of Cardiology) guidelines. The medical treatment yielded very good results in this case as the disappearance of vegetation mass as shown in Figure 19. Even though optimum management of tricuspid valve infective endocarditis has not yet been defined, it is a serious and potentially lethal condition in an infant or child [81] and so early surgical intervention to remove the large obstructive vegetation is indicated. The surgical treatment can be performed with low risk and good early, mid and long-term results [82].

References

- Moss, R., Munt,B. (2003). Injection Drug Use And Right-Sided Endocarditis. Heart, 89:577-581.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hecht, S., R., Berger, M. (1992). Right-Sided Endocarditis In Intravenous Drug Users. Prognostic Features In 102 Episodes, Annals of Internal Medicine, 17:560.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Watanakunakorn, C., Burkert, T. (1993). Infective Endocarditis At A Large Community Teaching Hospital,1980-1990. A Review of 210 Episodes, Medicine (Baltimore), 72(2):90-102.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fonager,K.,Lindberg,J.,Thulstrup,A.,M.,Pedersen,L.,Schonheyder,H.,C.,Sorensen,H.,T .(2003). Incidence And Short-Term Prognosis of Infective Endocarditis In Denmark, 1980-1997. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 35(1):27-30.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Walpot,J., Blok,W.,Von Zwienen,J., Klazen,C.,Amsel,B.,(2006). Incidence and Complication Rate of Infective Endocarditis In The Dutch Region of Walcheren: A 3-Year Retrospective Study. Acta Cardiologica, 61(2):175-181

Publisher | Google Scholor - Burke, A.,P., Kalra,P.,Li,L., Smialek,J.,Virmani,R. (1997). Infectious Endocarditis And Sudden Unexpected Death: Incidence And Morphology of Lesions In Intravenous Addicts And Non-Drug Abusers. Journal of Heart Valve Disease, 6(2):198-203

Publisher | Google Scholor - Habib,G.,Lancellotti,P.,Antunes,M.,J.,et al. (2015). ESC (European Society of Cardiology) Guidelines For The Management of Infective Endocarditis. European Heart Journal, 36:3075-3128.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Murdich,D.,R.,Corey,G.,R.,Hoen,B.,et al. (2009). Clinical Presentation, Etiology, And Outcome of Infective Endocarditis In The 21st Centuary: An International Collaboration On Endocarditis- Prospective Cohort Study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169:463-473.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Stull,T.,L., LiPuma,J.,J. (1992). Endocarditis In Children. In: Kaye,D.,ed. Infective Endocarditis. 2nd Ed. New York: Raven, 313-327.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chen,S.,C., Dwyer,D.,E., Sorrell,T.,C. (1992). A Comparison of Hospital and Community- Acquired Infective Endocarditis. American Journal of Cardiology, 70(18):1449-1452.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Osler,W.,(1885). Gustonian Lectures On Malignant Endocarditis, Lancet,1: 415-418.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bass,N.,M.,Sharatt,G.,J.,P. (1973). Left Atrial Myxoma Diagnosed By Echocardiography With Observations On Tumor Movement. British Heart Journal, 35:1332.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jung Min Bae, Yeon Hyeon Choe, Hye Won Hwang, Jung-Sun Kim, Wook Sung Kim, Kyong Ran Peck, Sung-Ji Park. (2015). Tumor-Mimicking Large Vegetation Attached to The Tricuspid Valve Without Predisposing Factors. A Case Report on CT and Echocardiographis Findings. Journal of The Korean Society of Radiology, 73 (4):269-273, Figure 1 A.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mazzeffi,M., Reich,D.,L., Adams,D.,H., Fischer,G.,W. (2011). A Mitral Valve Mass: Tumor, Thrombus, or Vegetation:? Journal of Cardiothoracic And vascular Anesthesia, 25:889-890.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Harvey Feigenbaum, William F. Armstrong, Thomas Ryan. (2005). Masses, Tumors, And Source of Embolism, Feigenbaum’s Echocardiography. Sixth Edition, 21:703.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lewis,T., Grant,R.,T. (1923). Observations Relating To Subacute Infective Endocarditis. Heart, 10:21

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gould,K.,Ramirez-Ronda,C.,H.,Holmes,R.,K., et al. (1975). Adherence of Bacteria To Heart Valves In Vitro. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 56:1364-1370

Publisher | Google Scholor - Song, M.,H., Usui,M., Usui,A., et al (2001) Giant Vegetation Mimicking Cardiac Tumor In Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis After Catheter Ablation, Japanese Journal of Thoracic And Cardiovascular Surgery, 49:255-257.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Furui,M.,Ohashi,T.,Yoshida,T.,et al. (2010). Ventricular Septal Perforation Caused By Right-Sided Infective Endocarditis Associated With Giant Vegetation. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 89:959-961

Publisher | Google Scholor - Oka,M., Angrist,A.,(1965) Comparative Histochemical Studies of Nonbacterial And Bacterial Valvular Vegetations. Laboratory Investigation, 14:48-61.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Scheld,W.,M., Valone,J.,A., Sande,M.,A. (1978). Bacterial Adherence in The Pathogenesis of Endocarditis. Interaction of Bacterial Dextran, Platelets, And Fibrin. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 61:1394

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kuypers,J.,M.,Proctor,R.,A. .(1989). Reduced Adherence to Traumatized Rat Heart Valve By A Low- Fibronectin-Binding Mutant of Staphylococcus Aureus. Infection and Immunity (American Society for Microbiology), 57:2306.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yeh,C.,Y.,Chen,J.,Y.,Chia,J.,S. (2006). Glucosyltransferases of Viridans Group Streptococci Modulate Interleukin-6 And Adhesion Molecule Expression in Endothelial Cells And Augment Monocytic Cell Adherence. Infection And Immunity, 74(2):1273-1283

Publisher | Google Scholor - Reynon,R.,P.,et al. (2006). Infective Endocarditis. British Medical Journal, 333:334-339.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Freedom,L.,R.,Valone,J.,Jr. (1979). Experimental Infective Endocarditis, Progress In Cardiovascular Diseases. 22:169.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Moss,R., Munt,B. (2003). Injection Drug Use And Right Sided Endocarditis. Heart, 89:577-581.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Weinstein,L. (1986). Life-Threatening Complications of Infective Endocarditis And Their Management. Archives of Internal Medicine, 146:953.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yvorchuk, K.,J., Chan,K.,L. (1994). Application of Transthoracic and Transesophageal Echocardiography In The Diagnosis And Management of Infective Endocarditis. Journal of American Society of Echocardiography, 7:294.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ali Akbar Heydari, Hossein Safari, Mohammad Reza Sarvghad (2009) Isolated Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 13(3):e109-e111.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Goodwin,J.,F. (1963). Diagnosis of Left Atrial Myxoma. Lancet, 1:464.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Skanse,B.,Berg,N.,O.,Westfelt,L. (1959). Atrial Myxoma With Raynaud Phenomenon As The Initial Symptom. Acta Medica Scandinavica, 164:321.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Van Hare,G.,F., Ben-Shachar,G., Liebman,J.,et al. (1984). Infective Endocarditis In Infants And Children During The Past 10 Years: A Decade of Change. American Heart Journal, 107:1235-1240.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Li, J.,S., Sexton,D.,J., Mick,N.,et al. (2000). Proposed Modifications to The Duke Criteria For The Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 30:633-638.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Prashanth Panduranga, Seif Al-Abri, Jawad Al-Lawati. (2013). Intravenous Drug Abuse And Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis: Growing Trends In The Middle East Gulf Region. World Journal of Cardiology, 5 (11):397-403.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Syed T. Hussain, James Witten, Nabin K. Shrestha, Eugene H. Blackstone, Gosta B. Pettersson. (2017). Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis, Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 6 (3):255-261.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Han Ying Liu, Ioannis Panidis, Joseph Soffer, Leonard S. Dreifus. (1983). Echocardiographic Diagnosis of Intracardiac Myxomas, Chest, 84(1):62-67.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nelson B. Schiller, Bryan Ristow, Xiushui Ren (2018). Role of Echocardiography in Infective Endocarditis.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alarcon,A., Villanueva,J.,L. (1998). Endocarditis In Parenteral Drug Addicts. Right-Sided Endocarditis. Influence of HIV Infection. Revista Espanola De Cardiologia, 51(S2):71-78.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adolf W. Karchmer. (2001). Infective Endocarditis. Braunwald Heart Disease, A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 6th Edition, 47:1734.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Adnan S.Dajani, Kathryn A. Taubert. (2001). Infective Endocarditis. Moss And Adams, Heart Disease in Infants, Children, And Adolescents. 6th Edition, 11:1304.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rubinstein,et al .(1974). Tissue Penetration of Amphotericin B In Candida Endocarditis. Chest. 66:376.

Publisher | Google Scholor - MacCallum D. M., Whyte,J.,A., Odds,F.,C. (2005). Efficacy of Caspofungin and Voriconazole Combinations In Experimental Aspergillosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 49:3697-3701.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kupferwasser L I, Yeaman M R, Shapiro S M, et al. (1999). Acetylsalicylic Acid Reduces Vegetation Bacterial Density, Hematogenous Bacterial Dissemination, And Frequency of Embolic Events in Experimental Staphylococcus Aureus Endocarditis Through Antiplatelet and Antibacterial Effects. Circulation, 99(21):2791-2797.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cenap Ozkara, Omer Faruk Dogan, Cevdet Furat. (2012). Isolated Tricuspid Valve Infective Endocarditis in Young Drug Abusers. World Journal of Cardiovascular Diseases, 2:201-203.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gottardi R, Bialy J, Devyatko E. (2007). Midterm Follow-Up of Tricuspid Valve Reconstruction Due to Active Infective Endocarditis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 84(6):1943-1948.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nishimura R A, Otto C M, Bonow R O, et al. (2014). AHA/ACC Guideline for The Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation,129:2440-2492.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Prendergast B D, Tornos P. (2010). Surgery for Infective Endocarditis. Who And when? Circulation, 121:1141-1152.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dawood M Y, Cheema F H, Ghoreishi M, et al. (2015). Contemporary Outcomes of Operations for Tricuspid Valve Infective Endocarditis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 99:539-546.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Morokuma H, Minato N, Kamohara K, Minematsu N. (2010). Three Surgical Cases of Isolated Tricuspid Valve Infective Endocarditis. Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 16:134-138.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, Thuny F, Prendergast B, Vilacosta I, et al. (2009). Guidelines on The Prevention, Diagnosis, And Treatment of Infective Endocarditis (New Verson 2009). European Heart Journal, 30:2369-2413.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, Vilacosta I, Zamorano J L, Galderisi M, et al. (2010). Recommendations For the Practice of Echocardiography in Infective Endocarditis. European Association of Echocardiography. European Journal of Echocardiography, 11:202-219.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tricuspid Valve Infective Endocarditis. (2018). University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akinosoglou K, Apostolakis E, Koutsogiannis N, et al. (2012). Right-Sided Infective Endocarditis: Surgical Management. European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 42:470-479.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tarola C L, Losenno K L, Chu M W. (2015). Complex Tricuspid Valve Repair For Infective Endocarditis: Leaflet Augmentation, Chordae And Annular Reconstruction. Multmedia Manual of Cardiothoracic Surgery.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arbulu A, Holmes R J, Asfaw I. (1993). Surgical Treatment of Intractable Right-Sided Infective Endocarditis In Drug Addicts: 25-Year Experience. Journal of Heart Valve Disease, 2:129-137.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gaca J G, Sheng S, Daneshmand M, et al. (2013). Current Outcomes For Tricuspid Valve Infective Endocarditis Surgery In North America. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 96:1374-1381.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Newman H A, Cordell A R, Prichard R W. (1966). Intracardiac Myxomas: Literature Review and Report of Six Cases, One Successfully Treated. Annals of Surgery, 32:219-230.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kabbani S S, Cooley D A. (1973). Atrial Myxoma: Surgical Considerations. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 65:731.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mesnildrey P, Bloch G, Cachera J P, Piwnica A. (1989). Atrial Myxoma: A New Surgical Approach Using Neodynium: Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet Laser Photocoagulation. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 98:313.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Talebi S, Xin Tan B E, Gazali R M, Herzog E. (2017). Last Resort: Successful AngioVac of Fungal Tricuspid Valve Vegetation. QJM (Quarterly Journal of Medicine): An International Journal of Medicine/Oxford Academic, 110(10):673-674.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Makdisi G, Casiani T, Wazniak T C, Roe D W, Hashmi Z A. (2016). A Successful Percutaneous Mechanical Vegetation Debulking Used as A Bridge to Surgery in Acute Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 8:E137-139.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Thiagaraj A K, Malviya M, Htun W W, Telila T, Lerner S A, Elder M D, et al. (2017). A Noval Approach in The Management of Right-Sided Endocarditis: Percutaneous Vegectomy Using the AngioVac Cannula. Future Cardiology, 13:211-217.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Allen Patrick Burke. (2016). Pathology of Infectious Endocarditis. The Heart Org Medscape.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Baraki H, Saito S, Al Ahmad A, et al. (2013). Surgical Treatment for Isolated Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis-Long-Term Follow-Up at A Single Institution. Circulation Journal, 77:2032-2037.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mugge A, Daniel W G, Frank G, Lichtlen P R. (1989). Echocardiography In Infective Endocarditis: Reassessment of prognostic implications of Vegetation Size Determined by The Transthoracic and The Transesophageal Approach. Journal of American College of Cardiology, 14:631-638.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sanfillipo A J, Picard M H, Newell J B, Rosas E, Davidoff R, Thomas J D, et al. (1991). Echocardiographic Assessment of Patients with Infectious Endocarditis: Prediction of Risk for Complications. Journal of American College of Cardiology, 18:1191-1199.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ashraf Tavanii Sani, Maryam Mojtabavi, Reza Bolandnazar. (2009). Effect of Vegetation Size on The Outcome of Infective Endocarditis in Intravenous Drug Users. Iranian Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 4(3):129-134.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Thuny F, Di Salvo G, Belliard O, Avierinos J F, Pergola V, Rosenberg V, et al. (2005). Risk of Embolism and Death in Infective Endocarditis: Prognostic Value of Echocardiography: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Circulation, 112(1):69-75.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Martin-Daliva P, Navas E, Fortun J, Moya J L, Cobo J, Pintado V, et al. (2005). Analysis of Mortality and Risk Factors Associated with Native Valve Endocarditis in Drug Users: The Importance of Vegetation Size. American Heart Journal, 150(5):1099-1106.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Barbour D J, Roberts W C. (1986). Valve Excision Only Versus Valve Excision Plus Replacement for Active Infective Endocarditis Involving the Tricuspid Valve. American Journal of Cardiology, 57:475-478.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yee E S, Ullyot D J. (1988). Reparative Approach for Right-Sided Endocarditis. Operative Considerations and Results of Valvuloplasty. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 96:133-140.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Larsson S, Lepore V, Kennergren C. (1989). Atrial Myxomas: Results of 25-Years’ Experience and Review of The Literature. Surgery, 105:695.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bortolloti U, Maraglino G, Rubino M, et al. (1990). Surgical Excision of Intracardiac Myxoma: A 20-Year Follow-Up. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 49:449.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zitnik R S, Giuliani E R. (1970). Clinical Recognition of Atrial Myxomas. American Heart Journal, 80:689-700.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Waller D A, Ettles D F, Saunders N R, WilliamsG. (1989). Recurrent Cardiac Myxoma: The Surgical Implications of Two Distinct Groups of Patients. The Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeon, 37:226-230.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Terada Y, Wanibuchi Y, Noguchi M, Mitsui T. (2000). Metastatic Atrial Myxoma to The Skin At 15 Years After Surgical Resection. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 69:283-284.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Stimmel B, Donoso E, Dack S. (1973). Comparison of Infective Endocarditis in Drug Addicts and Nondrug Users. American Journal of Cardiology, 32:924-929.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Levine D P, Crane L R, Zervos M J. (1986). Bacteremia In Narcotic Addicts At The Detroit Medical Center. II. Infectious Endocarditis: A Prospective Comparative Study. Reviews of Infectious Diseases, 8:374-396.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Abe K, Nakamura S, Ninomiya T, et al. (1996). Infective Endocarditis Caused by Campylobactor Fetus After Allogeneic Tooth Transplantation: A Case Report. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 34:230-234.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tally J D, Wenger N K. (1987). Atrial Myxoma: Overview, Recognition and Management. Comprehensive Therapy, 13:12-18.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Solomon E Levin, Raymond Dansky, Avran Benatar, Selwyn Milner. (1992). Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis on A Healthy Valve-Potentially Lethal in Infants and Young Children, Cardiology in The Young. Cambridge Core, 2(2):191-195

Publisher | Google Scholor - Musci M, Siniawski H, Pasic M, et al. (2007). Surgical Treatment of Right-Sided Active Infective Endocarditis with or Without Involement of The Left Heart: 20-Year Single Center Experience. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, 32:118-125.

Publisher | Google Scholor