Research Article

Pressure Ulcers and Associated Factors Among Adult Patients Admitted to The Surgical Wards in The Comprehensive Specialized Hospital of The Northwest Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia

1School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia.

2School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Habtamu Bekele Beriso, School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia.

Citation: Habtamu B. Beriso, Zemene W., Tesfaye E. (2024). Atypical Radiological Findings in Colloid Cyst of Third Ventricle- Rare Findings in Rare Tumour. Scientific Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 1(6):1-14. DOI: 10.59657/2996-8550.brs.24.021

Copyright: © 2024 Habtamu Bekele Beriso, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: June 27, 2024 | Accepted: September 04, 2024 | Published: November 11, 2024

Abstract

Introduction: Pressure ulcers are a serious concern in patients with prolonged bedtime and present with common complications following surgery. It is one of the key performance indicators of the quality of nursing care provided to patients. Several studies have reported the prevalence of pressure ulcers in Ethiopia, but the current study area has not yet been fully addressed. Hence, the study aims to assess pressure ulcers and their associated factors among adult patients admitted to the surgical ward. Method: An institution-based, cross-sectional study was conducted from April 15 to May 15, 2023. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select 480 patients. A standardized, pre-tested, and structured questionnaire was used. The results were presented descriptively using tables and figures. A binary logistic regression was used to assess associated factors.

Results: From a total of 480, all patients have participated with a 100% response rate. The prevalence rate of pressure ulcers was 10.2%. Being smoker (95% CI: AOR 7.46 (2.64, 21.06), bedridden (95% CI: AOR 3.92 (1.28, 11.66), having a length of hospital stay of greater than 20 days (95% CI: AOR 3.01 (1.13, 8.02), experiencing pain (95% CI: AOR 3.20 (1.06, 7.51), or having friction and shear (95% CI: AOR 5.71 (1.91, 17.08), were significantly associated with pressure ulcers.

Conclusion: This study showed that a considerable proportion of patients had pressure ulcers. Smoking, having pain, being bedridden, being exposed to friction and shear problems, and length of hospital stay were significantly associated with pressure ulcers. Healthcare providers should educate patients about smoking risks, pain management, mattress installation, and linen care.

Keywords: bedsore; pressure ulcer; surgical patients; ethiopia

Introduction

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are impairments of the skin and below-surface tissue produced by pressure, shearing, and frictional forces [1,2]. Different scholars call pressure ulcers different but are often used interchangeably, these include decubitus ulcers; bed sores, and pressure injuries [3,4]. According to a global systematic review, the prevalence of pressure ulcers ranges from 0.4% to 38% among surgical patients [5,6] In the United States, 2.5 million people are at risk of developing pressure ulcers each year, and 60,000 of them die as a result of complications in surgical patients. All of these conditions still occur frequently in people of all ages and a variety of settings after surgery [7,8]. In Africa, it reportedly ranges from 3.8% to 19.3% among hospitalized patients [9,10]. It remains a common complication following surgery, with a mean reported prevalence of 25%-30% during inpatient care [11]. The deleterious consequences of persistent pressure on bony prominences worsen as surgical procedures continue to lengthen and as patient transplants are repositioned during surgery. The risk of developing a pressure ulcer is increased by preoperative medication-induced immobility, friction forces applied during medical examinations, and delayed mobilization in the postoperative phase [12,13]. The development of pressure ulcers is influenced by surgical factors in three stages: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative. Postoperative factors included the amount of time needed to return the body temperature to normal, wetness, body position, activity, and mobility. [14,15. The occurrence of a pressure ulcer has several negative effects, including discomfort, the need for additional treatments, an extended hospital stays, deformation and scarring of the body, increased morbidity, and increased medical expenses. Additionally, it was found that the cost per patient increased by 3–4 times when pressure injuries from surgical operations occurred, and PU also results in a poor prognosis and increased patient mortality, placing a significant burden on patients' families and society as a whole [16,17,18]. According to some international practice guidelines, patients and caregivers should be encouraged to actively participate in the prevention of their own PUs by learning about the conditions and participating in a variety of intervention programs, such as care bundles, prophylactic dressings, support surfaces, repositioning, preventive skin care, system reminders, and staff training [19,20]. However, various studies have shown that these preventive measures for PUs have not been fully applied [21,22]. Therefore, PU is a prevalent and burdensome condition with a substantial negative impact on surgical patients, healthcare systems, and socioeconomic costs [23]. Although pressure ulcers are a significant global public health problem, there is a dearth of evidence regarding their magnitude and associated factors in the current study area. Providing information for policymakers and health care providers by identifying major factors associated with pressure ulcers to improve patient management services, set priorities for interventions, improve the quality of care for surgical patients, and bring awareness of this issue to all other caregivers through an accurate estimation of the prevalence and contributing factors of this problem is useful to effectively manage this issue. Therefore, this study assessed the prevalence and contributing factors of PUs in surgical units. An accurate estimation of the prevalence of pressure ulcers in comprehensive specialized hospitals in northwestern Ethiopia will help in making healthcare decisions to control this problem.

Methods and Materials

Study design and period

We conducted an institutional-based cross-sectional study in specialized hospitals in the Northwest Amhara Region between April 15 and May 15, 2023.

Study Setting

This institutional-based hospital is located in the northwestern region of the country. According to the 2007 Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, the Amhara National Regional State has a total population of 17,221,976, of which 8,641,580 are male and 8,580,396 are female. There are five comprehensive specialized hospitals in the Northwest Amhara Region of Ethiopia: the University of Gondar, Tybee Ghion, Fleeger Hiwot, Debre Markos, and Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. From these five comprehensive specialized hospitals, three were randomly selected: the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (UoGCSH) with 78 beds in the surgical wards, the Fleeger Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (FHCSH) with 109 beds in the surgical wards, and the Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DTCSH) with 46 beds in the surgical wards. The average total number of admitted surgical patients in the past month was 670.

Population

All patients admitted to the Northwest Amhara Regional State Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals were considered the source population. We randomly selected patients admitted to surgical wards during the study period from April 15 to May 15, 2023, as the study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients admitted to the surgical wards of the hospital for more than two days before data collection were included in the study. Patients aged less than 18 years, unable to provide consent, critically ill patients who are unable to communicate, or admitted for the second time during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined by using the single population proportion formula with a 95% confidence interval, a 5% margin of error, and adding 10% for the no response rate. The proportion of pressure ulcers was 25.3%[24]. This was obtained from a previous cross-sectional study conducted at the Debre Birhan Specialized Hospital, North Shoa Zone, Ethiopia.

n= =

= =290.4

=290.4

where n= sample size, Z = 1.96; P = 0.253; d = 0.05

By considering a 10% non-response rate (290.4*10/100) =29.04 ~29à nf=291+29= 320 surgical patients have participated. The final sample size was adjusted by adding a 1.5 design effect of 480.

Sampling technique and procedure

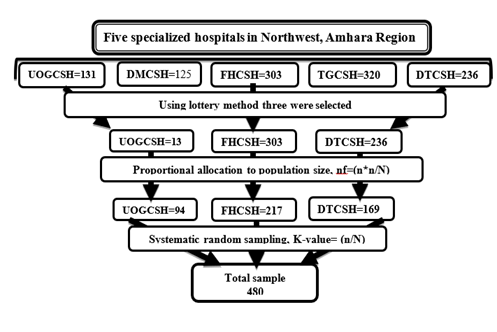

The names of the hospitals are the University of Gondar, Tibebe Ghion, Felege Hiwot, Debre Markos, and Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. From these three comprehensive specialized hospitals, three were randomly selected: the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (UoGCSH) with 78 beds in the surgical wards, the Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (FHCSH) with 109 beds in the surgical wards, and the Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DTCSH) with 46 beds in the surgical wards. The total number of study participants was proportionally distributed to different segments of the surgical ward. Study participants were obtained using a systematic random sampling technique with every other patient admitted to the surgical ward selected for the interview using k-value = 670/480 = 1.39. The total number of study participants was proportionally distributed to different segments in the surgical ward according to the number of patients admitted from their admission registration book. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure

Data collection tools and procedures

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews via structured questionnaires and observation. A standardized, pre-tested, and structured questionnaire prepared in English was used from different literature. The questionnaire includes three sections: Section one: socio-demographic variables such as age, sex, residence, marital status, educational status, and monthly income. Section two: health facility-related variables (such as length of hospital stay, supportive device use, position change, bedridden status, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol use) and Section three: Braden Risk Assessment Scale (RAS), such as sensory perception, moisture, activity, friction/shear, mobility, and nutrition; and Section 4: Oslo Social Support Scale, such as The data was collected using face-to-face interviews and physical examination via observation of the predominant pressure site based on the lying position. Sometimes it can be recorded in the patients’ charts. Alongside pressure and risk assessment.

Study variables

Dependent variable

Pressure Ulcer

Independent variables

The sociodemographic and economic variables included age, sex, residence, marital status, educational status, and monthly income. The Braden Risk Assessment Scale (RAS) includes sensory perception, moisture, activity, friction/shear, mobility, and nutrition. The health facility-related factors included length of hospital stay, supportive device use, position change, bedridden status, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol use. Oslo social support scale: poor, moderate, and strong social support.

Operational definition

According to the pressure ulcer, it damages an area of the skin because of constant pressure on that area for a long time [25]. For this study, patients who noticed skin lesions on body parts such as the sacrum, shoulder, or heels upon observation and physical examination were included.

Braden risk assessment Factors: This tool assesses factors associated with pressure ulcers; we call these tools the Braden scales of PU risk assessment tools, which include six components: sensory perception, moisture, activity, friction or shear, mobility, and nutrition, collectively classified as high, moderate, or low risk [26].

Pain assessment: assessed Patients who scored a numeric pain rating scale of 0 were considered to have no pain, while those who scored 1-3, 4-6, or 7–10 was considered to have mild, moderate, or severe pain, respectively [27].

Smoking status: Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes during your life?" Respondents who answered "yes" were classified as ever smokers, and those who answered "no" were classified as never smokers [28]. Bedridden patients who are unable to leave the bed [29].

Social support: is defined as the physical and psychological comfort provided by other people. Measurement for social support According to the Oslo Social Support Scale-3 (OSSS-3), those who scored 3–8 was considered to have poor social support, 9–11 moderate social support, and 12–14 strong social support [30].

Alcohol drinking status: is classified as never for those who never consume any alcoholic drinks; those who consumed alcohol at the time of data collection are current drinkers; and those who consumed alcohol in the past but stopped one year ago are past alcohol drinkers [31].

Data quality assurance

Before the actual data collection, the questionnaires were pre-tested on 5% (24) of surgical patients at Tybee Ghion Specialized Hospital to assess clarity, sequence, consistency, understandability, and total time. Three BSc nurse data collectors who are fluent in the local language and familiar with the local customs and an MSc supervisor were selected and assigned to check daily for the completeness, clarity, and consistency of the questionnaire and to give appropriate support during the data collection process. One-day training was given to data collectors and supervisors by the principal investigator. Finally, necessary comments and feedback were incorporated into the final instrument.

Data Management and Analysis

The data were coded and entered into the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20, after which the analyses were performed. Descriptive results are presented in tables, graphs, and figures. A binary logistic regression was used; in bivariate analysis, variables with p values less than or equal to 0.25 were selected for multivariate analysis as less than 0.05, and the AOR at the 95% confidence interval was used to assess the presence and strength of the association between the independent variable and dependent variable, respectively.

Results

Sociodemographic information

Out of a total of 480 admitted patients, all patients participated in the study with a response rate of 100%. About 179 (37.3%) of the participants were in the age range of 18–34 years, 288 (60%) were male, 282 (58.8%) were Orthodox by faith, 247 (51.5%) were rural dwellers, 142 (39.6%) were unable to read and write, 337 (70.5%) were married, 119 (24.8%) were farmers, 183 (38.1%) had a low economic status, 442 (92.1%) never smoked cigarettes, 248 (51.7%) were alcohol drinkers, and 25 (5.4%) were alcohol drinkers (Table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographic information of patients admitted to surgical wards

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

| Age | 18-34 | 179 | 37.3 |

| 35-54 | 160 | 33.3 | |

| >54 | 141 | 29.4 | |

| Sex | Female | 192 | 40 |

| Male | 288 | 60 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 282 | 58.8 |

| Muslim | 110 | 22.9 | |

| Protestant | 53 | 11 | |

| Catholic | 35 | 7.3 | |

| Residence | Urban | 233 | 48.5 |

| Rural | 247 | 51.5 | |

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 142 | 39.6 |

| Primary from 1-8 | 96 | 20 | |

| Secondary from 9-12 | 105 | 21.9 | |

| Collage and above | 137 | 28.5 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 337 | 70.5 |

| Single | 69 | 14.4 | |

| Widowed | 44 | 9.1 | |

| Divorced | 30 | 6 | |

| Occupation | Gov.t employ | 123 | 25.6 |

| Farmer | 119 | 24.8 | |

| Merchant | 107 | 22.3 | |

| Student | 60 | 12.5 | |

| Daily labor | 42 | 8.8 | |

| Housewife | 29 | 6 | |

| Economic Status | Low | 183 | 38.1 |

| Mild | 180 | 37.5 | |

| High | 117 | 24.4 | |

| Smoking Status | No | 442 | 92.1 |

| Yes | 38 | 7.9 | |

| Alcohol drinking status | Current | 248 | 51.7 |

| Never | 207 | 43.1 | |

| Previous | 25 | 5.2 |

Hospital service-related factors

Among the participants, 62 (12.9%) were bedridden, 32 (51.6%) used a pressure-relieving device, 14 (48.4%) were positioned four times per day, 29 (46.0%) patients were positioned, and 183 (38.1%) had a length of stay in the hospital between 8 and 20 days. Of those who used medical devices, 50 (23%) were on fixation (Table 2).

Table 2: Hospital service-related information on patients admitted to surgical wards

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

| Patient bedridden | Yes | 62 | 12.9 |

| No | 418 | 87.1 | |

| Patient positioning | Yes | 29 | 46.0 |

| No | 33 | 54.0 | |

| Frequency of patient positioning | Every 2 to 3 hours | 6 | 20.6 |

| Every 4 hours | 9 | 31.0 | |

| Turned 4 times/day | 14 | 48.4 | |

| Patients with medical device | Yes | 220 | 45.8 |

| No | 260 | 54.2 | |

| Pressure relieving device | Yes | 32 | 51.6 |

| No | 30 | 48.4 | |

| Length of hospital stay | <8> | 190 | 39.6 |

| 8-20 days | 183 | 38.1 | |

| >20 days | 107 | 22.3 | |

| Types of medical devices | Fixation | 51 | 23 |

| Urinary catheter | 40 | 18 | |

| Splint and brace | 40 | 18 | |

| Traction | 33 | 15 | |

| Fecal containment | 32 | 15 | |

| Chest tube | 13 | 6 | |

| NG-Tube | 4 | 1.8 | |

| Endotracheal tube | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Face mask | 2 | 0.9 |

Clinical characteristics of the patients

Among the participants, 273 (56.9%) experienced pain, 70 (14.2%) had severe pain, 21 (5%) had edema, 436 (90.8%) were conscious, 423 (88.1%) had a normal BMI, and 32 (6.7%) had comorbid illnesses. Among comorbid illnesses, 44% (14) were anemic, and the reason for admission was fractured 118 (24.8%). Based on the grading scale, 44.8% (22), 48.9% (24), and 6.3% (3) developed stage I, stage II, and stage II, respectively, and mainly affected anatomical locations. 38.7% (19) were in the in the sacral region (Table 3).

Table 3: The clinical characteristics of patients admitted to surgical wards

| Variable | Response | Frequency | Percentage |

| Patient with pain | Yes | 273 | 56.9 |

| No | 207 | 43.1 | |

| Severity of pain | Mild | 95 | 19.8 |

| Moderate | 108 | 22.5 | |

| Sever | 70 | 14.2 | |

| Patients who have edema | Yes | 21 | 5 |

| No | 459 | 95 | |

| Grade of edema | Grade I | 13 | 72 |

| Grade II | 8 | 28 | |

| Patient levels of consciousness | Unconscious | 44 | 9.2 |

| Conscious | 436 | 90.8 | |

| Patients BMI | Normal | 423 | 88.1 |

| Underweight | 25 | 5.2 | |

| Overweight | 32 | 6.7 | |

| Comorbid illness | Yes | 27 | 5.6 |

| No | 453 | 94.4 | |

| Types of co-morbid illness | Anemia | 12 | 44.4 |

| Hypertension | 5 | 18.5 | |

| DM | 6 | 22.2 | |

| Tuberculosis | 2 | 7.42 | |

| HIV/AIDS | 1 | 3.74 | |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 3.74 | |

| Reason for admission | Fractures | 118 | 24.8 |

| Road traffic accidents | 62 | 13 | |

| Appendicitis | 56 | 12.7 | |

| Bowel obstructions | 26 | 5.4 | |

| Grade of pressure ulcer | Stage I | 22 | 44.8 |

| Stage II | 24 | 48.9 | |

| Stage III | 3 | 6.3 | |

| Anatomical locations | Sacral | 19 | 38.7 |

| Greater trochanter | 15 | 30.6 | |

| Shoulder | 12 | 24.5 | |

| Occipital | 1 | 0.02 | |

| Heel | 1 | 0.02 | |

| Elbow | 1 | 0.02 |

Hospital service-related information

Among the participants, 12.9% (62) were bedridden, 32 (51.6%) used a pressure relieving device, 14 (48.4%) four times per day frequency of positioning, 29 (46.0%) patients being positioned, 183 (38.1%) had a length of stay in the hospital between 8 and 20 days, 45.8% of those used medical devices from these, 50 (23%) were on fixation, and 38.1% (183) had poor social support based on OSLO Social Support Scale-3 (Table 4).

Table 4: Hospital service-related information on patients admitted to surgical wards

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

| Patient bedridden | Yes | 62 | 12.9 |

| No | 418 | 87.1 | |

| Patient positioning | Yes | 29 | 46.0 |

| No | 33 | 54.0 | |

| Frequency of patient positioning | Every 2 to 3 hours | 6 | 20.6 |

| Every 4 hours | 9 | 31.0 | |

| Turned 4 times/day | 14 | 48.4 | |

| Patients with medical device | Yes | 220 | 45.8 |

| No | 260 | 54.2 | |

| Pressure relieving device | Yes | 32 | 51.6 |

| No | 30 | 48.4 | |

| Length of hospital stay | <8> | 190 | 39.6 |

| 8-20 days | 183 | 38.1 | |

| >20 days | 107 | 22.3 | |

| Types of medical devices | Fixation | 51 | 23.0 |

| Urinary catheter | 40 | 18.0 | |

| Splint and brace | 40 | 18.0 | |

| Traction | 33 | 15.0 | |

| Fecal containment | 32 | 15.0 | |

| Chest tube | 13 | 6.0 | |

| NG-Tube | 4 | 1.8 | |

| Endotracheal tube | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Face mask | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Social support | Poor | 183 | 38.1 |

| Moderate | 202 | 42.1 | |

| Strong | 95 | 19.8 |

Braden Risk Assessment Scale report of the patients

According to Braden Risk Assessment Scale; 333 (69.4%) of the patients had no limitation on sensory perception, 176 (36.7%) had occasionally moist, 196 (40.8%) walked occasionally, 164(34.2%) were slightly limited in mobility, 17.3% (83) had very poor in nutrition, and 45 (9.4%) had problems with friction and shear (Table 5).

Table 5: Patient information about the use of the Braden Risk Assessment Scale (RAS) in surgical wards

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

| Sensory perception | Completely limited | 26 | 5.4 |

| Very limited | 51 | 10.6 | |

| Slightly limited | 70 | 14.6 | |

| No limitation | 333 | 69.4 | |

| Moisture | Constantly moist | 77 | 16.0 |

| Very moist | 115 | 24.0 | |

| Occasionally moist | 176 | 36.7 | |

| Rarely moist | 112 | 23.3 | |

| Activity | Bed fast | 82 | 17.1 |

| Chair fast | 155 | 32.3 | |

| Walks occasionally | 196 | 40.8 | |

| Walks frequently | 45 | 9.4 | |

| Mobility | Completely immobile | 57 | 11.9 |

| Very limited | 110 | 22.9 | |

| Slightly limited | 164 | 34.2 | |

| No limitation | 149 | 31.0 | |

| Nutrition | Very poor | 85 | 17.7 |

| Most likely inadequate | 159 | 33.1 | |

| Adequate | 153 | 31.9 | |

| Excellent | 83 | 17.3 | |

| Friction and shear | No apparent problem | 323 | 67.3 |

| Potential problem | 112 | 23.3 | |

| Problem | 45 | 9.4 |

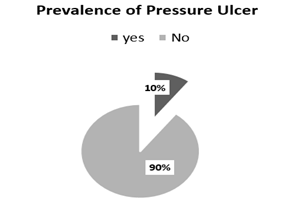

Prevalence of Pressure Ulcer

Of a total of 480, 49 (10.2%) of the patients admitted to the surgical ward had pressure ulcers (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prevalence of pressure ulcers among patients admitted to surgical wards

Factors Associated with Pressure Ulcers among Admitted Patients

In bivariate analysis; alcohol consumption status, smoking status, pain status, bedridden status, educational status, use of Braden’s risk assessment tools (sensory perception, moisture, mobility, friction, and shear), length of hospitalization, and social support whose p values were less than 0.25 were significantly associated with the outcome variables. However, in the multivariate analysis, smoking status, pain, bedridden status, friction and shear problems, and length of hospital stay were independently associated with pressure ulcers. The results of multivariate analysis showed that bedridden patients were 3.92 times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer than patients who were not bedridden. The odds of developing a pressure ulcer among patients who experienced pain were 3.21 times greater than those among patients who did not experience pain Patients who had a problem with friction and shear were 5.71 times more likely to have a pressure ulcer than patients who had no apparent problem with friction and shear Patients who being smoking were 7.46 times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer than those who were not smoking Patients who had stayed in the hospital for >20 days were 3.004 times more likely to have pressure ulcers than those who had stayed in the hospital for 8 days (Table 6).

Table 6: Bivariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with pressure ulcers

| Variables | Pressure ulcer | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Smoking status | ||||

| No | 33 | 409 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 16 | 22 | 9.02(4.32,18.81) | 7.46(2.64,21.05) *** |

| Alcohol status | ||||

| Never | 10 | 195 | 1 | 1 |

| Current | 33 | 214 | 3.01(1.30,5.12) | 1.41(0.56,3.46) |

| Previous | 6 | 22 | 5.32(0.58,8.46) | 0.91(0.14,6.01) |

| Educational status | ||||

| Unable to read and write | 18 | 119 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary from 1-8 | 11 | 131 | 0.55(0.25,1.22) | 0.49(0.17,1.45) |

| Secondary from 9-12 | 10 | 86 | 0.76(0.33,1.48) | 0.732(0.24,2.17) |

| College and above | 10 | 95 | 0.69(0.31,1.58) | 0.73(0.24,2.15) |

| Patient experiences pain | ||||

| No | 8 | 199 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 41 | 232 | 4.39(2.02,9.59) | 3.21(1.06,7.52) * |

| The patient on bedridden | ||||

| No | 28 | 390 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 21 | 41 | 7.13(3.72,13.68) | 3.92(1.28,11.67) * |

| Sensory perception | ||||

| No impairment | 19 | 314 | 1 | 1 |

| Completely limited | 10 | 16 | 10.33(4.13, 25.82) | 3.08(0.72,13.18) |

| Very limited | 12 | 39 | 5.08(2.29,11.26) | 2.64(0.78,8.87) |

| Slightly limited | 8 | 62 | 2.13(0.89,5.08) | 1.21(0.38,3.84) |

| Moisture | ||||

| Rarely moist | 8 | 104 | 1 | 1 |

| Constantly moist | 16 | 61 | 3.41(1.38,8.43) | 2.14(0.61,7.56) |

| Very moist | 15 | 100 | 1.95(0.24,1.16) | 1.31(0.39,4.34) |

| Occasionally moist | 10 | 166 | 0.78(0.29,2.04) | 0.66(0.19,2.26) |

| Mobility | ||||

| No limitation | 8 | 141 | 1 | 1 |

| Completely limited | 19 | 38 | 8.82(3.58,21.86) | 2.54(.57,11.27) |

| Very limited | 13 | 97 | 2.36(0.94,5.92) | 2.49(0.65,9.56) |

| Slightly limited | 9 | 155 | 1.023(0.38,2.72) | 1.471(0.43,5.08) |

| Friction and shear | ||||

| No apparent, problem | 8 | 104 | 1 | 1 |

| Potential problem | 32 | 291 | 1.43(1.17,9.06) | 0.95(0.27,3.36) |

| Problem | 9 | 39 | 3.00(0.64,3.20) | 5.71(1.91,17.08) ** |

| Oslo social support scale | ||||

| Strong | 6 | 93 | 1 | 1 |

| Moderate | 13 | 200 | 1.01(0.37,2.73) | 0.73(0.21,2.61) |

| Poor | 30 | 138 | 3.37(1.35,8.41) | 2.28(0.68,7.59) |

| Length of hospital stay | ||||

| <8> | 13 | 177 | 1 | 1 |

| 8-20 days | 16 | 167 | 1.31(0.61,2.79) | 1.43(0.55,3.75) |

| >20 days | 20 | 87 | 3.13(1.48,6.58) | 3.01(1.13,8.02) * |

*P less than 0.05; **P less than 0.01; ***P less than 0.001

Discussion

The proportion of pressure ulcers among patients admitted to the surgical ward of the Northwest Amhara Regional Selective Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals during the study period was 10.2%, 95% CI (7.7, 12.9). These findings are consistent with those of the studies conducted in Istanbul 12.8%, Thailand 11.6%, Turkey 11.4%, and Hawassa 8.3% [31- 34]. The prevalence in the current study was lower than studies conducted in Qatar 50%, Iran 20.54%, Palestine 33%, other studies conducted in Ethiopia; Dessie 14.9%, Debre Brihan 25.3%, and Felege Hiwot 16.8% [24, 35-38]. This could be due to variations in the study settings and designs. In addition, this might be due to differences in patient characteristics, disease conditions in hospitals, factors such as nursing care service availability, awareness, and training concerning secondary conditions, and previous studies that included all wards. However, study-specific variations in Qatar have utilized only geriatric patients. The convenience sampling method was used in the Iranian study, and ICU patients were included in the Palestinian study. Reflecting the diversity of the study participants' socio-cultural status. This result was slightly greater than that of studies conducted in Australia 2.6%, in China, 1.6%, and in Ethiopia Wolaita, 3.4% [40-42]. The possible reasons for these discrepancies might explain the greater prevalence in this study, which may be linked to the small sample size of the studies in Wolaita; the finding from Australia was based on a prospective cohort study design; and the diversity of the study participants' cultures, the difference in quality of care provided, and good feeding habits in China. Additionally, the variations can be related to instruction and adherence to procedures for pressure ulcer prevention. Inadequate nursing care, very poor feeding practices, and a lack of funding for pressure-relieving equipment have led to little attention being given to pressure ulcers. This study revealed that the development of a pressure ulcer was strongly associated with an increased duration of hospital stay. Those who stayed 21 days were 3.01 times more likely to develop pressure ulcers as compared to those who stayed 8 days after admission to the hospital. These findings are in agreement with those of studies conducted in Qatar, Germany, Finland, and Woliata[35,43-45]. This is because patients who stay in the hospital for an extended period frequently do not have a stable situation, which adversely affects their general health and puts them at risk, perhaps increasing their susceptibility to pressure ulcers. This might also be because the main illness that requires patient admission requires more attention than any subsequent secondary conditions, and patients might not receive proper nursing care accordingly. Thus, regular follow-up and monitoring of individuals who stay in the hospital for extended periods of time are important for the early identification and prevention of this complication. This study revealed that the smoking status of patients was significantly associated with the development of pressure ulcers; patients being smoked were 7.46 times more likely to develop pressure ulcers. These findings are supported by studies conducted in Arkansas and the U.S. [46,47]. This might be due to toxins in cigarette smoke that harm collagen formation, tensile strength, skin integrity, and immune system function, and another reason might be that smoking activates our body's sympathetic nervous system, which has a vasoconstriction impact that decreases blood flow to the target organ, depriving the skin of oxygen and nutrients [48]. Therefore, the integrity and tensile strength of our skin are compromised. Therefore, informing patients who have smoked about the risks and complications of smoking and ensuring regular follow-up and monitoring of these individuals are appropriate to reduce this complication. According to the current study, bedridden status was significantly associated with the development of pressure ulcers, and patients were nearly four times more likely to develop pressure ulcers. A similar study was conducted in Woliata, and the findings in Jimma agreed with these findings [29,42]. The possible reasons include remaining in a single place for an extended period to damage skin tissues by compressing blood vessels and nerve endings and more than a dearth of advocates for appropriate patient handling practices and the use of glide sheets and patient transfer devices to lessen the damaging effects of friction and shear on the skin. In the present study, a high percentage of bedridden patients had pressure ulcers. These findings suggested that regular positioning of bedridden patients is preferable for preventing skin damage. Proper tissue perfusion and sufficient blood flow to the skin are thought to guarantee. This study also demonstrated that the likelihood of developing a pressure ulcer among patients who reported pain was 3.20 times greater than that among those who reported no pain. These findings are in agreement with studies in the UK and Norway [49,50]. This could be attributed to several factors. First, patients with pain tend to become restless, which causes their skin to shrink while they are in bed because they are brittle. In addition, pain causes anxiety which stimulates catecholamine hormones and reduces the amount of nutrients and oxygen delivered to the skin through avulsion. As a result, patients' skin integrity is damaged, and their physical and mental limitations generally increase [51]. The absence of oxygen for several days can cause widespread ischemic necrosis and ulceration of the skin. In the present study, 41 (84%) of the patients who experienced pain developed pressure ulcers suggesting that pain is one of the main contributing factors to this problem, therefore, special attention and anti-pain or prophylaxis are provided to patients who are experiencing pain to prevent this problem.

Patients who had a problem with friction and shear were 5.71 times more at high risk of developing pressure ulcers than those who had no apparent problem with friction or shear. These findings are consistent with the findings of studies conducted in Hawassa, Pakistan, and, Kenya, these findings revealed that patients who had problems with friction and shear were at greater risk than those with no apparent problems with friction or shear [34,53,54]. Possible explanations include the possibility that individuals who fail to keep their body upright on a bed or wheelchair may have their skin slide over the support surface, leading to blood vessel damage, irritation, and skin necrosis, which can cause a pressure ulcer.

The limitations of this study include interobserver bias, and the results might be better if, a prospective study is conducted to determine the incidence of pressure ulcers.

Conclusion and recommendations

The proportion of pressure ulcers among patients admitted to surgical wards was considerable. The associated factors were smoking status, patient pain, bedridden status, problems with friction and shear, and length of hospital stay. Therefore, healthcare providers should educate patients about the risks of smoking, proper management of pain, correct mattress installation, keep bed linens unwrinkled and smooth, avoid small particles irritating the skin, and maintain patients in a proper position on the bed, all of which are very important for the prevention or reduction of friction or shearing forces. Future studies should consider prospective (follow-up) studies to examine patients' knowledge of pressure ulcers.

Abbreviations

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio;

BMI: Body Mass Index;

CI: Confidence Interval;

DMCSH: Debre-Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital;

DTCSH: Debre-Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital;

FHCSH: Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital;

PU: Pressure Ulcer;

TGCSH: Tibebe Gihon Comprehensive Specialized Hospital;

UOGCSH: University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

Disclosures

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge officials at different levels and the participants who responded without restriction.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the College of Medicine and Health Science (ethical approval number S/N/172/2015). This study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki, which guides researchers in protecting their research subjects. This study was approved by the institutional research review committee of the University of Gondar. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that participation was beneficial, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection.

Consent to Publish and contribution of authors

The author HBB, contributed to the acquisition of the data, analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the article, and the authors WZ, and ET participated fully in revising the article and agreed on the journal to which the article will be sent for publication.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper and others necessarily data found on the corresponding author only shared with a reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

No funding

References

- Gül A, Sengul T, Yavuz HÖJJoTV. (2021). Assessment of the risk of pressure ulcer during the perioperative period: adaptation of the Munro scale to Turkish. 30(4):559-565.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kottner J, Cuddigan J, Carville K, Balzer K, Berlowitz D, Law S, Litchford M, Mitchell P, Moore Z, Pittman JJJoTV. (2020). Pressure ulcer/injury classification today: An international perspective. 29(3):197-203.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sifir CKJHSJ. (2022). Prevalence of Bed-Sore and its Associated Factors among Hospitalized Patients in Medical and Surgical Wards at Yekatit 12 Hospital Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 16(1):1-5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alkareem DAJIJoS. (2022). Etiological Study between Iraqi Patients with Bed Sore and Hospitalized Control.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chen H-L, Chen X-Y, Wu J. (2012). The incidence of pressure ulcers in surgical patients of the last 5 years: a systematic review. Wounds: A Compendium of Clinical Research and Practice, 24(9):234-241.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ünver S, Fındık ÜY, Özkan ZK, Sürücü ÇJJotv. (2017). Attitudes of surgical nurses towards pressure ulcer prevention, 26(4):277-281.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Khojastehfar S, Ghezeljeh TN, Haghani SJJotv. (2020). Factors related to knowledge, attitude, and practice of nurses in intensive care unit in the area of pressure ulcer prevention: a multicenter study. 29(2):76-81.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Martins de Oliveira AL, O'Connor T, Patton D, Strapp H, Moore ZJJowc. (2022). Sub-epidermal moisture versus traditional and visual skin assessments to assess pressure ulcer risk in surgery patients, 31(3):254-264.

Publisher | Google Scholor - GBADAMOSI IA, KOLADE OA, AMOO PO. (2023). Effect of Intervention Training on Nurses’ Knowledge of Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment and Prevention at a Tertiary Hospital, Nigeria.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zhang N, Yu X, Shi K, Shang F, Hong L, Yu JJJotv. (2019). A retrospective analysis of recurrent pressure ulcer in a burn center in Northeast China, 28(4):231-236.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chello C, Lusini M, Schilirò D, Greco SM, Barbato R, Nenna AJIWJ. (2019). Pressure ulcers in cardiac surgery: Few clinical studies, difficult risk assessment, and profound clinical implications, 16(1):9-12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Haugen V, Pechacek J, Maher T, Wilde J, Kula L, Powell JJJoWO. (2011). Nursing C. Decreasing pressure ulcer risk during hospital procedures: a rapid process improvement workshop, 38(2):155-159.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Karahan E, Ayri AU, Çelik S. (2022). Evaluation of pressure ulcer risk and development in operating rooms. Journal of Tissue Viability, 31(4):707-713.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Aghale MJTJoP, Rehabilitation. (2021). The Effect of Silicone Pad on the Heel and Sacral Pressure Ulcer in Patients Undergoing Orthopedic Surgery Maedeh Alizadeha, Somayeh Ghavipanjehb, Aylin Jahanbanc, Esmaiel Maghsoodid, 32:3.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Galivanche AR, Kebaish KJ, Adrados M, Ottesen TD, Varthi AG, Rubin LE, Grauer JNJJ-JotAAoOS. (2020). Postoperative pressure ulcers after geriatric hip fracture surgery are predicted by defined preoperative comorbidities and postoperative complications. 28(8):342-351.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ramezanpour E, Zeydi AE, Gorji MAH, Charati JY, Moosazadeh M, Shafipour VJJoN, Sciences M. (2018). Incidence and risk factors of pressure ulcers among general surgery patients. 2018, 5(4):159.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fu Shaw L, Chang P-C, Lee J-F, Kung H-Y, Tung T-HJBri. (2014). Incidence and predicted risk factors of pressure ulcers in surgical patients: experience at a medical center in Taipei, Taiwan.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zhu Y, Luo M, Liu Q, Liu HJAJTR. (2023). Preventive effect of cluster nursing on pressure ulcers in orthopedic patients and predictive value of serum IL-6 and TNF-α for the occurrence of pressure ulcers, 15(2):1140-1149.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chaboyer W, Bucknall T, Webster J, McInnes E, Gillespie BM, Banks M, Whitty JA, Thalib L, Roberts S, Tallott M et al. (2016). The effect of a patient-centered care bundle intervention on pressure ulcer incidence (INTACT): A cluster randomized trial. International journal of nursing studies, 64:63-71.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gaspar S, Peralta M, Marques A, Budri A, Gaspar de Matos MJIwj. (2019). Effectiveness on hospital‐acquired pressure ulcers prevention: a systematic review, 16(5):1087-1102.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bååth C, Idvall E, Gunningberg L, Hommel A. (2014). Pressure-reducing interventions among persons with pressure ulcers: results from the first three national pressure ulcer prevalence surveys in Sweden. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 20(1):58-65.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sving E, Idvall E, Högberg H, Gunningberg L. (2014). Factors contributing to evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention. A cross-sectional study. International journal of nursing studies, 51(5):717-725.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hajhosseini B, Longaker MT, Gurtner GCJAos.(2020). Pressure injury, 271(4):671-679.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shiferaw I, Tadesse N, Shiferaw S. (2022). Prevalence and Associated Factors of Pressure Ulcer among Hospitalized Patients in Debre Birhan Referal Hospital, North Shoa Zone, Amhara, Debre Birhan, Ethiopia. Health Science Journal, 16(10):1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sardo PMG, Guedes JAD, Alvarelhão JJM, Machado PAP, Melo EMOP. (2018). Pressure ulcer incidence and Braden subscales: Retrospective cohort analysis in general wards of a Portuguese hospital. Journal of Tissue Viability, 27(2):95-100.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sardo PM GJ, Alvarelhão JJ, Machado PA, Melo EM. (2018). Pressure ulcer incidence and Braden subscales: Journal of Tissue Viability, 1(27(2)):95-100.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Orr PM, Shank BC, Black AC. (2017). m the role of pain classification systems in pain management. Critical Care Nursing Clinics, 29(4):407-418.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ryan H, Trosclair A, Gfroerer J. (2012). Adult current smoking: differences in definitions and prevalence estimates—NHIS and NSDUH, 2008. Journal of environmental and public health.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Assefa T, Mamo F, Shiferaw D. (2017). Prevalence of bed sore and its associated factors among patients admitted at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia, 2017 cross-sectional study. Orthopedics and Rheumatology Open Access Journals, 8(4):74-81.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kocalevent RD, Berg, L., Beutel, M. E., Hinz, A., Zenger, M., Härter, M., ... & Brähler, E. (2018). Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3). BMC psychology, 6(1):31.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tyrovolas S, Panaretos D, Daskalopoulou C, Gine-Vazquez I, Niubo AS, Olaya B, Bobak M, Prince M, Prina M, Ayuso-Mateos JL. (2020). Alcohol drinking and health in aging: a global scale analysis of older individual data through the harmonized dataset of ATHLOS. Nutrients, 12(6):1746.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Suttipong C, Sindhu S. (2012). Predicting factors of pressure ulcers in older Thai stroke patients living in urban communities. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(3‐4):372-379.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Biçer EK, Güçlüel Y, Türker M, Kepiçoglu NA, Sekerci YG, Say A. (2019). Pressure ulcer prevalence, incidence, risk, clinical features, and outcomes among patients in a Turkish hospital: a cross-sectional, retrospective study. Wound Manag Prev, 65(2):20-28.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ebrahim J, Deribe B, Biru W, Feleke T. (2018). Prevalence and factors associated with pressure ulcer among patients admitted in Hawassa University Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia. J Health Care Prev, 1(105):2.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nadukkandiyil N, Syamala S, Saleh HA, Sathian B, Ahmadi Zadeh K, Acharath Valappil S, Alobaidli M, Elsayed SA, Abdelghany A, Jayaraman K. (2020). Implementation of pressure ulcer prevention and management in elderly patients: a retrospective study in tertiary care hospital in Qatar. The Aging Male, 23(5):1066-1072.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rashvand F, Shamekhi L, Rafiei H, Nosrataghaei M. (2020). Incidence and risk factors for medical device‐related pressure ulcers: the first report in this regard in Iran. International Wound Journal, 17(2):436-442.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Qaddumi DJ, Almahmoud O. (2019). Pressure Ulcers Prevalence and Potential Risk Factors Among Intensive Care Unit Patients in Governmental Hospitals in Palestine: A Cross-sectional Study. The Open Public Health Journal, 12:121-126.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bereded DT, Salih MH, Abebe AE. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors of pressure ulcer in hospitalized adult patients; a single center study from Ethiopia. BMC research notes, 11:1-6.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gedamu H, Hailu M, Amano A: (2014). Prevalence and associated factors of pressure ulcer among hospitalized patients at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Advances in Nursing,

Publisher | Google Scholor - Webster J, Lister C, Corry J, Holland M, Coleman K, Marquart L. (2015). Incidence and risk factors for surgically acquired pressure ulcers. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 42(2):138-144.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jiang Q, Li X, Qu X, Liu Y, Zhang L, Su C, Guo X, Chen Y, Zhu Y, Jia J et al. (2014). The incidence, risk factors and characteristics of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients in China. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology, 7(5):2587-2594.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arba A, Meleku M, Nega A, Aydiko E. (2020). Bed-sore and Associated Factors Among Patients Admitted at Surgical Wards of Wolaita Sodo University Teaching and Referral Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 8(4):62-68.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Petzold T, Eberlein‐Gonska M, Schmitt J. (2014). Which factors predict incident pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients? A prospective cohort study. British Journal of Dermatology, 170(6):1285-1290.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Koivunen M, Hjerppe A, Luotola E, Kauko T, Asikainen P. (2018). Risks and prevalence of pressure ulcers among patients in an acute hospital in Finland. Journal of Wound Care 27(Sup2): S4-S10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Belachew T. (2016). Prevalence and associated factors of pressure ulcer among adult inpatients in Wolaita Sodo University Teaching Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Prevalence, 6(11).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Krause JS, Vines CL, Farley TL, Sniezek J, Coker J. (2001). An exploratory study of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: relationship to protective behaviors and risk factors. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 82(1):107-113.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Saunders LL, Krause JS. (2010). Personality and Behavioral Predictors of Pressure Ulcer History. Topics in spinal cord injury rehabilitation, 16(2):61-71.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gonzalez JE, Cooke WH. (2021). Acute effects of electronic cigarettes on arterial pressure and peripheral sympathetic activity in young nonsmokers. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 320(1): H248-H255.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Skogestad IJ, Martinsen L, Børsting TE, Granheim TI, Ludvigsen ES, Gay CL, Lerdal A. (2017). Supplementing the Braden scale for pressure ulcer risk among medical inpatients: the contribution of self-reported symptoms and standard laboratory tests. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(1-2):202-214.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Smith IL, Brown S, McGinnis E, Briggs M, Coleman S, Dealey C, Muir D, Nelson EA, Stevenson R, Stubbs N et al: Exploring the role of pain as an early predictor of category 2 pressure ulcers: a prospective cohort study. BMJ open, 7(1): e013623.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Charalambous C, Vassilopoulos A, Koulouri A, Eleni S, Popi S, Antonis F, Pitsilidou M, Roupa Z. (2018). The Impact of Stress on Pressure Ulcer Wound Healing Process and the Psychophysiological Environment of the Individual Suffering from them. Medical Archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina), 72(5):362-366.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akram J, Samdani K, Afzal A, Khan TM, Umar W, Bibi S, Mumtaz M, Zehra H, Rasool F, Javed K. (2022). Bed Sores and Associated Risk Factors Among Hospital Admitted Patients: A Comparative Cross-sectional Study. American Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing Practice, 7(4):17-25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sisimwo PK, Margai M, Obaigwa E, Mbatha A, Mutua A, Atieno W. (2021) Prevalence and risk factors for Pressure ulcers among adult inpatients at a tertiary referral hospital Kenya.

Publisher | Google Scholor