Research Article

Physical Assaults to Pregnant Women, Community Based Study in A Rural, Remote Region

1Senior Consultant, Obstetrics Gynaecology, Tapan Bhai Mukesh Bhai Patel Memorial Hospital, Medical College, and Research Centre, Shirpur, Dhule, Maharashtra, India.

2Resident, Obstetrics Gynaecology, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical sciences, Maharashtra, India.

*Corresponding Author: Shakuntala Chhabra, Senior Consultant, Obstetrics Gynaecology, Tapan Bhai Mukesh Bhai Patel Memorial Hospital, Medical College, and Research Centre, Shirpur, Dhule, Maharashtra, India.

Citation: Chhabra S., Nawandar R. (2025). Physical Assaults to Pregnant Women, Community Based Study in A Rural, Remote Region, Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology Research, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 4(1):1-9. DOI: 10.59657/2992-9725.brs.25.023

Copyright: © 2025 Shakuntala Chhabra, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: December 16, 2024 | Accepted: March 14, 2025 | Published: March 28, 2025

Abstract

Background: It is being opined that physical assaults (PA) may be more common problem in pregnant women than some conditions for which they are routinely screened and evaluated.

Objectives: Community based study was conducted to know about PA reported by rural, tribal pregnant women of rural remote region.

Material and Methods: Information about assaults to pregnant women at home, at work places was collected by interviews using tool, with some questions for yes or no answers, others short answers. It was prospective, longitudinal study in 140 villages around village with health facility, study center, in hilly forestry region. Randomly included minimum 10 women from each village made a total of 2000 women of 20 to 49 years, study subjects.

Results: Of 2000 pregnant women, 1490 (74.5%) reported PA at home, more of illiterate (91%) reported PA. No graduate reported PA. All economic classes except upper economic class reported PA. Most women had 1 or 2 births (n=636) 330 were with first pregnancy. In most cases of PA at home, perpetrators were husbands (72.55%) and in 516 (34.64%) PA were regular affair. Of 2000 pregnant women, 1460 (73%) reported PA at workplaces, perpetrators were employers in 61.84% A small number graduate and upper class too were assaulted at work places. Of 1490 women, almost 99% informed someone, family member (81%), police (16.9%). Over all 71.5% women sought health care.

Conclusion: Study revealed that PV during pregnancy was up to 75%at home work places in many once or occasional but almost one third on regular basis. It affected their own, their baby’s health. They did take action, with not much of impact. Many sought health cares. It is essential that society as a whole looks into it.

Keywords: rural; pregnant women; physical assaults; prelabor rupture of membranes

Introduction

It is being opined that physical assaults (PA) may be a more common problem in pregnant women than some conditions for which they are routinely screened and evaluated. PA to pregnant women is a global health issue. Awareness of health sector about PA during pregnancy is also increasing. Assaults during pregnancy can cause vaginal bleeding, abortion, preterm pains and preterm birth, prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM), low birth weight, foetal \neonatal death, and can cause severe sickness or even death of the mother [1-3]. Dinmohammadi et al [4] opined that house hold assaults during pregnancy might be the most common social problem which affect the health of the mother and the fetus, major challenge to health system. Objectives: Community based study was conducted to know about PA suffered by rural, tribal pregnant women of a remote region.

Material and Methods

Information about assaults to pregnant women at home and at work places was collected by interviews using a tool, with some questions for yes or no answers and others short answers. After consent women were interviewed by the research assistant in villages at mutually convenient places. Information up to culmination of pregnancy was recorded on the hard tool. No one was given tool to fill.

Study Design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Study Setting: The study was carried out in 140 villages around the village with a health facility in one village, study center in a hilly forestry region.

Study Sample: Randomly included minimum 10 pregnant women from each village made a total of 2000 pregnant women of 20 to 49 years became study subjects, calculated study sample [5,6].

Inclusion Criteria: Pregnant women of 20to 49yrs and willing to be part of the study.

Exclusion Criteria: Non pregnant women, those less than 20 or more than49 yrs. of age and those who did not want to be part of study. However, in quite a few ages was calculated as they did not know.

Results

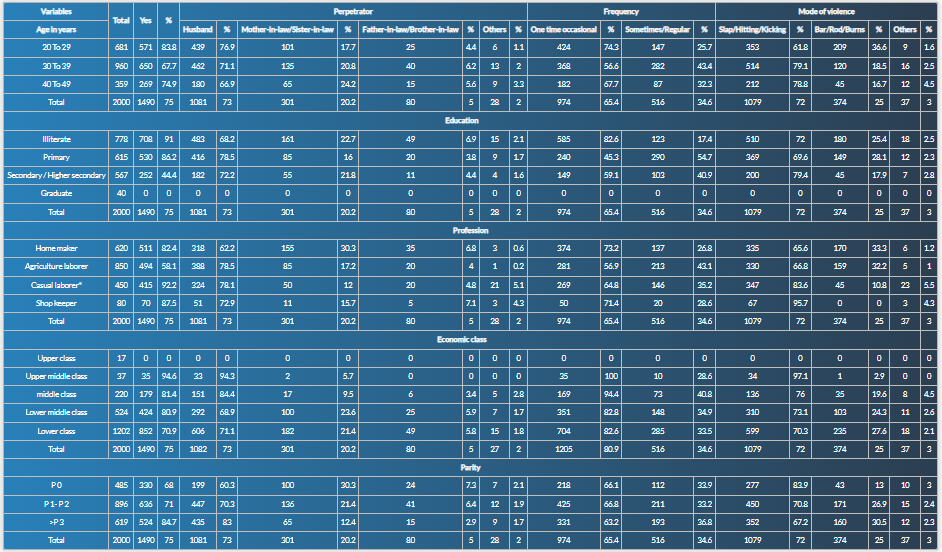

Among 2000 study subjects, 681 (34.05%) were of 20-29 years, 960 (48%) 30-39 years, and 359 (17.95%) 40-49 years of age. Total 778 (38.9%) study subjects were illiterate, 615 (30.75%) had primary, 567 (28.35%) secondary or higher secondary education, and 40 (2%) were graduates. Of all study subjects, 620 (31%) were homemakers, 850 (42.5%) agricultural laborer’s, 450 (22.5%) casual laborers [working in small scale (food, shoes making, bamboo items) industries, welding workshops, brick furnaces] and 80 (4%) women were shopkeepers. Total 1202 (60.1%) women were from very low economic class, 524 (26.2%) from low economic class, 220 (11%) lower middle, 37 (1.85%) from middle, and 17 (0.85%) were from upper economic class (village level economic grade). Total 485 (24.25%) women were pregnant for the first time, 896 (44.8%) had one or two births, and 619 (30.95%) had3 or more births. Of the 2000 pregnant women, 1490 (74.5%) reported PV at home. Most of these women were of 30-39 years of age (n=650), however significantly more women of 20-29 years age (n=571) around 84% reported PA compared to around 68% in 30 to 39yrs of age (P value 0.005). Very significantly more illiterate (n=708) women 91% reported PA compared to those with secondary school studied, 44% and no graduate reported PA at home (P value 0.001). Signicantly less agricultural laborers reported PA, 58% compared to others around 90% (P-value 0.005). All economic classes, very low economic class (n=852), low class (n=424), lower middle class (n=179), and middle class (n=35) reported PA, however no cases of PA were reported by women belonging to upper economic class. Most women had 1 or 2 births (n=636), 524 had 3 or more births and 330 were first time pregnant for the first time. Percentage of those who reported PA was signicantly higher, 84% amongst those with many births compared to 68% in others, (P-value 0.05). In most cases of PV at home, the perpetrators were the women’s husbands (n=1081, 72.55%), however husbands were Signicantly more often responsible for PA, 94% in better economic classes than mother-in-law or sister-in-law or others 6% compared to low economic class (P-value 0.05). In some, PA was once or occasional as reported by 974(65.36%) women but in 516(34.64%) women PA was a regular affair. Mode of PA reported was slapping, hitting with rods even burn. Assaults with bar/ rod/ burns significantly more often reported by younger, illiterate and women from very low economic class (P-value 0.001). Relationship with various variables is depicted in table 1 (Table 1).

Table 1: Physical Assaults Reported by Pregnant Women at Home.

*Small Scale, (Food, Shoes making, Bamboo items) Industry, Welding Workshop, Brick furnace

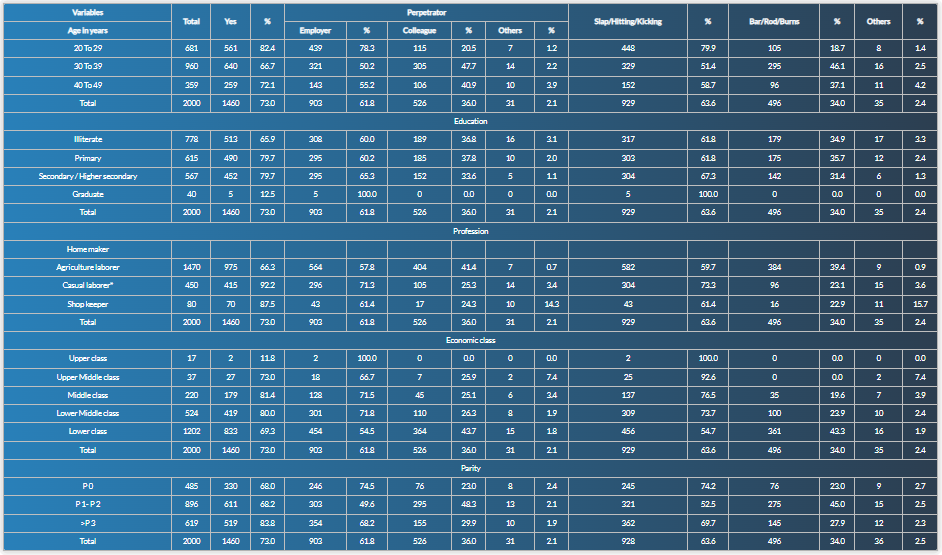

Of the 2000 pregnant women, 1460 (73%) reported PA at workplaces. Most of these women were between 30-39 years of age (n=640) followed by 20-29 years age group (n=561) and 40-49 age group (n=259). Most women were illiterate (n=513) with primary education (n=490), secondary or higher secondary education (n=452), and graduates (n=5). Most women were agricultural laborers (n=975), followed by casual laborers (n=415), and shopkeepers (n=70). Most women were from very low economic class (n=833), low class (n=419), low middle class (n=179), middle class (n=27), and upper class (n=2). Most women were having 1 or 2 (n=611) births, 519 women had 3 or more (n=519) births and 330 were pregnant for the first time. Relationship with variables is depicted in table 2 (Table 2).

Table 2: Physical Assaults Reported by Pregnant Women at Work Places.

*Small Scale, (Food, Shoes making, Bamboo items) Industry, Welding Workshop, Brick furnace

In most cases of PA at workplaces, the perpetrators were the women’s employers (n=903, 61.84%) followed by colleagues (n=526, 36%) and others (n=31, 2.12%). (n=571). However, employers were significantly more often reported by younger women and colleagues by elder (P-value 0.05). The mode of PA was slapping/ hitting/ kicking in 929(63.63%) women, PA with bar/ rod/ burns were reported by 496(33.97%) women and other modes of PA were reported by 35(2.39%) women. Most women were illiterate (n=663) with primary education (n=485), and those with secondary or higher secondary education (n=252). Most women were agricultural laborers (n=494), homemakers (n=466), casual laborers (n=370), and shopkeepers (n=70). However, percentage of those who reported PA was more amongst agricultural laborers at work places. (P-value 0.05) Most women were from very low economic class (n=852), followed by low economic class (n=332), lower middle class (n=179), and middle class (n=20). Most women were having 1 or 2 (n=746), births followed by women (n=385) with no previous birth and those with 3 or more births were 269 (Table 2).

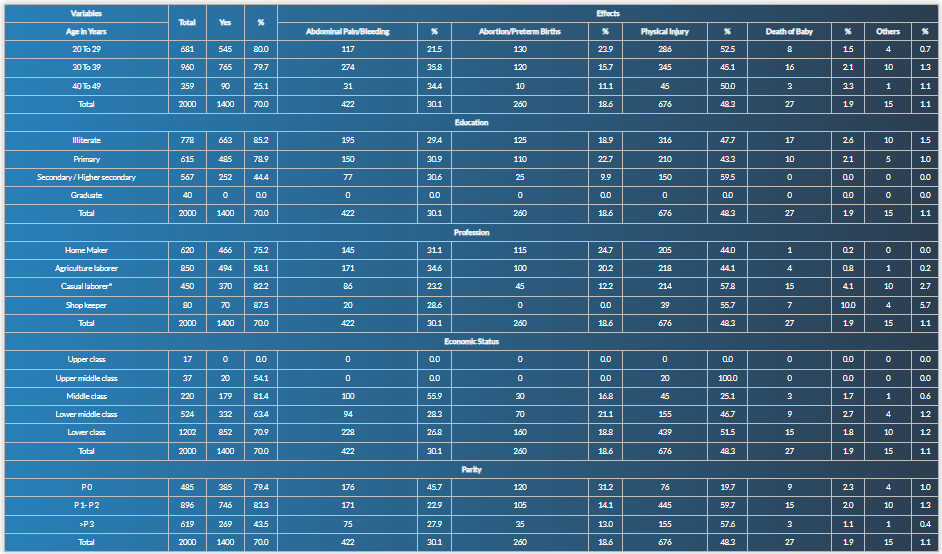

Of 2000 women, 1400(70%) reported some effects on themselves or their babies. Physical injury was the most common effect reported, 676(48.3%) women, followed by abdominal pain or bleeding in 422(30.1%), abortion or preterm births in 260(18.6%), death of baby in 27(1.9%), and other effects were reported by 15(1.1%). Most of these women were between 30-39 years of age (n=765), 20-29 years of age (n=545) and 40-49 age group (n=90). Most women were illiterate (n=663) with primary education (n=485), and those with secondary or higher secondary education (n=252). Most women were agricultural laborers (n=494), homemakers (n=466), casual laborers (n=370), and shopkeepers (n=70). Most women were from very low economic class (n=852), low class (n=332), lower middle class (n=179), and middle class (n=20). Most women were having 1 or 2 (n=746), births, 385with no previous birth and those with 3 or more births were 269 as depicted in table 3 (Table 3).

Table 3: Effects of Physical Assaults in Pregnant Women.

*Small Scale, (Food, Shoes making, Bamboo items) Industry, Welding Workshop, Brick furnace

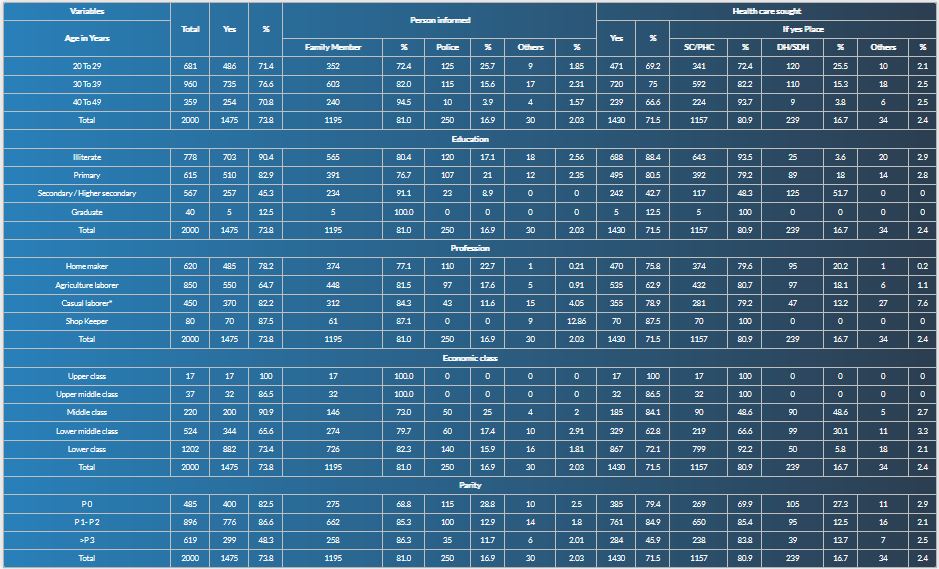

However, it was not a case control study. Information being shared is what was told by women and what was in their records. There could have been other causes, not part of this study. Of 1490 women, 1475, almost, 99%took some action after they suffered PA at home or workplaces, in the form of informing someone, most commonly family member (n=1195, 81%), police (n=250, 16.9%), or others (n=30, 2.03%). Over all 1430(71.5%) women sought health care, 1157(80.9%) at Sub Centers (SCs) or Primary Health Centers (PHCs), 239(16.7%) at district hospital (DH) or sub district hospital (SDH), and 34 (2.4%) at other places as depicted in Table 4.

Table 4: Action Taken by Women Who Reported Assaults.

*Small Scale, (Food, Shoes Making, Bamboo Items) Industry, Welding Workshop, Brick furnace. SC-Sub Centre; PHC-Primary Health Centre; DH-District Hospital; SDH-Sub District Hospital

Discussion

PA during pregnancy is known to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, still it continues to be a global health issue. The prevalence of PA among pregnant women is reported with wide variation from 1.6% to 66% [1-3]. In the present study which was of rural women and community based, around 75% pregnant women reported PA at home during pregnancy and 73% at work places too. Glander et al [5] many years back reported that a high proportion (39.5%) of women seeking abortion were victims of household assaults during pregnancy in USA. Studies from around the world have revealed that violence during pregnancy was common in developing countries around 32%, and in industrialized countries 12% [6,7]. However, surveys did not include injury/violence during pregnancy. The first national femicide study in South Africa found that four women were killed every day by intimate partner in South Africa [8]. In the present community-based study in rural pregnant women, 20 to 100% women with different variables reported physical visible injury. There have been some health facility-based studies in South Africa which showed that 55% of pregnant women experienced physical/sexual violence in their lives [9]. Study by Dinmohammadi et al [4] revealed that compared to solution based focused counselling in terms of violence and quality of life women who had experienced domestic violence (DV) all types of violence significantly decreased in the intervention group compared to no intervened with improved quality of life too. Community-based studies, especially amongst rural women about PA are not many, importance of present study, which revealed that around one third of pregnant women suffered PA on regular basis in villages with low resources.

Study by Munro-Kramer et al [10] in rural Zambia revealed that women had experienced some type of physical IPV in the preceding 2 weeks (kicked, dragged, beaten, and/or choked by husband or partner). Being a female head of a household was associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing severe physical IPV. Antai et al [11] reported that women who had experienced physical and sexual violence, IPV were more likely to have terminated a pregnancy compared to women who had not experienced. In the present study no one talked of termination, but many women reported effects on pregnancy, even abortions and preterm births. Around 70% to 100% women varying with different variables sought health care. Atsbaha et al [12] opined that IPV was high among pregnant women in Ethiopia, but the cases were under-reported and the reported IPV during pregnancy was 36.3%. Lack of formal schooling, rural life, husband’s additional sexual partners, lack of shared decisions, and partners’ alcohol intake were identified as predictors of IPV. In the present study also husbands were mostly responsible, more so in young women, illiterate and those from low and very low economic class. It is important to consider raising awareness, enhancing women’s decision-making abilities, and educating them. Gazmararian et al [14] reported that of thirteen studies selected on the basis of specific criteria revealed that the prevalence of violence during pregnancy ranged from 0.9% to 20.1%. The lowest estimate was reported by women who attended a private clinic and responded to a self-administered questionnaire provided to them by a person who was not a health care provider. Turan et al [14] did a study about the program for prevention and mitigation of the effects of violence among pregnant women at an antenatal clinic in rural Kenya and reported that the pregnancy was acceptable and feasible, as it aided pregnant women in accessing services and raised awareness. In the present study numbers were high. The need is that society looks at it as a crime against women.

Study by Small et al [15] done in Haitian pregnant women revealed that 44.0% women had experienced violence in the 6 months prior to interview and 77.8% of them reported that the violence was perpetrated by an IP. Those who experienced IPV reported significantly greater pregnancy-related symptoms. No significant differences between violence perpetrated by family members or others and reporting of symptoms were observed. Abdollahi et al [16] reported that violence against women during pregnancy was widespread in Iran and had linkage to poor pregnancy outcome. They did a study and reported that the prevalence of IVP was high among pregnant women and they had 1.9-fold risk of PROM, and a 2.9-fold risk of low birth weight compared to women who did not experience any violence. Nasir et al [17] reviewed studies from developing countries and reported that the prevalence of violence among pregnant women in developing countries ranged from 4% to 29% and the main risk factors were, low-income group, low education in both partners, and unplanned pregnancy. Ziaei et al [18] reported that in rural women in Bangladesh lifetime DV was 57%. Peedicayil et al [19] did a study about PA during pregnancy and the factors associated with it, in rural, urban slum and non-slum areas in some cities of India and reported 12.9% of women experienced moderate to severe PA during pregnancy. Suspicion of infidelity, dowry issues, husband being regularly drunk and low education of husband were the main risk factors.

Ntaganira et al [20] did a study among Rwandan pregnant women and found 35% IPV in the last 12 months, in the form of pulling hair, slapping, kicking with fists, throwing on the ground and kicking with feet, burning with hot liquid. Shamu et al [21] reported that IPV was very high in Africa and their review of studies revealed 2% to 57% the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy major risk factors included HIV infection, history of violence and alcohol and drug use. Elkhateeb et al [22] from Egypt have reported that the prevalence of violence among pregnant women was 50.8%. Exposure to violence during pregnancy had significant effects on women and pregnancy outcome because of possibility of vaginal infection, vaginal bleeding, preterm labor, and premature rupture of membranes. One of the most important risk factors was the fear of the husband which made violence a continuous vicious circle. Fisher et al [23] did a study in rural Vietnam and reported that exposure to either lifetime or perinatal IPV including emotional abuse, PV and SV were associated with increased common perinatal mental disorders (CPMD) and suicidal thoughts in women during pregnancy and after childbirth. Experiencing more than one form of IPV increased the magnitude of the association between IPV and CPMD and thoughts of suicide.

Karaoglu et al [24] reported that in Turkey, researchers reported that during pregnancy 31.7% of women suffered PA and opined low education of partners, low family income, husband's unemployment, urban settlement, unwanted pregnancy and smoking should alert health staff towards violence during pregnancy. Study by Shannon et al [25] from Appalachian North America revealed that the majority reported lifetime IPV, in conjunction with pervasive substance use, mental and physical health problems, and poverty present in rural Appalachia. Efetie et al [26] did a study in Nigeria and reported that while most (92.9%) women were aware of DV in pregnancy, 125 women (37.4%) had experienced DV. Of those who suffered violence, 21.2% required medical treatment. They were aware of possible pregnancy complications, abortion, premature labor and depression. Most (81.9%) of the respondents felt DV was illegal. A majority (29.7%) kept their DV secret with a few numbers reporting to family, doctors, clergy or close friends. With higher education, the experience of DV was greater, although this was not significant. Similarly, this tended to reverse after parity. Jamshidimanesh et al [27] did a study in Iran and reported that 56.3% reported DV during pregnancy. Prevalence rate of preterm labor was 37.7% among all women in the study, 63.3% of them were cases of abused women.

Akrami et al [28] also did a study in Iran and reported that the PV during pregnancy was 10.7%, physical abuse 3 months before pregnancy was 11.9%. Women who experienced PA compared with those not reporting abuse were more likely to be smoker and hospitalized for pregnancy related complications. There was a significant association between PA and low birth weight and mother’s education. Edin et al [29] did a study at antenatal clinics of Northern Sweden. The midwives, although very knowledgeable about and sensitive to pregnant women and their needs, still rarely revealed the occurrence of violence. Among pregnant women registered at the antenatal clinic, the midwives roughly estimated that the frequency of known cases of PV and SV before and during the index pregnancy were 2.3% and 0.6%, respectively for the preceding calendar year. The local programs for antenatal care provided no guidelines regarding response to violence, no instruments for disclosure and no directions about support when confronted with an abused pregnant woman. Rachana et al [30] did a study in Saudi Arabia and reported that the prevalence of PV was 21%. Women who experienced PA were more likely to be hospitalized during pregnancy for complications such as trauma due to blows/kicks on the pregnant abdomen, placental abruption pre-term labor and kidney infections. There was a positive association between PV during pregnancy and placental abruption, fetal distress, and prematurity cesarean section.

Jahanfar et al [31] examined the effectiveness and safety of interventions in preventing or reducing DV against pregnant women and reported limited evidence for the primary outcomes of reduction of episodes of violence during and up to one year after pregnancy. In one study, women who received the intervention reported fewer episodes of partner violence during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. However, there was insufficient evidence to assess the effectiveness of interventions for DV on pregnancy outcome. McFarlane et al [32] from Houston did a study and reported that repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that severity of abuse decreased significantly across time for all intervention groups. Abuse screening by itself, however, may be the most effective intervention to prevent abuse to pregnant women. Study by Pun et al [33] explored community perceptions of DV against pregnant women and reported that in Nepal the community recognized different forms of violence during pregnancy threatening women’s physical and psychological health and presenting obstacles to seeking antenatal care. Some types of culturally specific violence were considered particularly harmful, such as pressure to give birth to sons, denial of food, and forcing pregnant women to do hard physical work during pregnancy. Mehenge et al [34] did a study in Tanzania and reported 27% experiencing both physical and sexual IPV in the index pregnancy. Women who experienced physical and/or sexual IPV during pregnancy were significantly more likely to have moderate post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Study by Okour et al [35] from Jordon revealed that the prevalence of violence (any type) during pregnancy was 40.9%, PA was 34.7%. Future research that more accurately measures PA during pregnancy would contribute to more effective design and implementation of prevention and intervention strategies.

Conclusion

Present community-based study revealed that PV during pregnancy was up to 70%at home and work places also, almost one third on regular basis and it affected their health and their babies also. They did take action with not much of impact though man sought health care. It is essential that society as a whole look into it for eliminating PA to pregnant women completely.

References

- Sana, S. H., Makhdoom, S., Husain, S., Hira, A., Bano, K., et al. (2023). Frequency of Domestic Violence in Pregnancy and Its Adverse Maternal Outcomes Among Pakistani Women. African Health Sciences, 23(4):406-414.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jamali, S., Bigizadeh, S., Jahromy, F. H., Sharifi, N., Mosallanezhad, Z. (2019). Maternal and Neonatal Complications Following Domestic Violence During Pregnancy. J Res Med Dent Sci, 7(2):86-92.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elkhateeb, R., Abdelmeged, A., Ahmad, S., Mahran, A., Abdelzaher, W. Y., et al. (2021). Impact of Domestic Violence Against Pregnant Women in Minia Governorate, Egypt: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21:1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dinmohammadi, S., Dadashi, M., Ahmadnia, E., Janani, L., Kharaghani, R. (2021). The Effect of Solution-Focused Counseling on Violence Rate and Quality of Life of Pregnant Women at Risk of Domestic Violence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21:1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Glander, S. S., Moore, M. L., Michielutte, R., Parsons, L. H. (1998). The Prevalence of Domestic Violence Among Women Seeking Abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 91(6):1002-1006.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Petersen, R., Gazmararian, J. A., Spitz, A. M., Rowley, D. L., Goodwin, M. M., et al. (1997). Violence and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Review of The Literature and Directions for Future Research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 13(5):366-373.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. The Lancet, 359(9314):1331-1336.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mathews, S. (2004). Every Six Hours A Woman is Killed by Her Intimate Partner: A National Study of Female Homicide in South Africa. Gender and Health Research Group, Medical Research Council.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dunkle, K. L., Jewkes, R. K., Brown, H. C., Yoshihama, M., Gray, G. E., et al. (2004). Prevalence and Patterns of Gender-Based Violence and Revictimization Among Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Soweto, South Africa. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(3):230-239.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Munro-Kramer, M. L., Scott, N., Boyd, C. J., Veliz, P. T., Murray, S. M., et al. (2018). Postpartum Physical Intimate Partner Violence Among Women in Rural Zambia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 143(2):199-204.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Antai, D., Adaji, S. (2012). Community-Level Influences on Women's Experience of Intimate Partner Violence and Terminated Pregnancy in Nigeria: A Multilevel Analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12:1-15.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Atsbaha, M., Alemayehu, M., Mekango, D. E., Moges, S., Ejajo, T., et al. (2022). Prevalence and Associated Factors of Intimate Partner Violence Among Pregnant Women Attending Health Care Facilities, Northern Ethiopia: Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 42(5):1155-1162.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gazmararian, J. A., Lazorick, S., Spitz, A. M., Ballard, T. J., Saltzman, L. E., et al. (1996). Prevalence of Violence Against Pregnant Women. JAMA, 275(24):1915-1920.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Turan, J. M., Hatcher, A. M., Odero, M., Onono, M., Kodero, J., et al. (2013). A Community-Supported Clinic-Based Program for Prevention of Violence Against Pregnant Women in Rural Kenya. AIDS Research and Treatment, 1:736926.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Small, M. J., Gupta, J., Frederic, R., Joseph, G., Theodore, M., et al. (2008). Intimate Partner and Non-Partner Violence Against Pregnant Women in Rural Haiti. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 102(3):226-231.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Abdollahi, F., Abhari, F. R., Delavar, M. A., Charati, J. Y. (2015). Physical Violence Against Pregnant Women by An Intimate Partner, And Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Mazandaran Province, Iran. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 22(1):13-18.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nasir, K., Hyder, A. A. (2003). Violence Against Pregnant Women in Developing Countries: Review of Evidence. The European Journal of Public Health, 13(2):105-107.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ziaei, S., Frith, A. L., Ekström, E. C., Naved, R. T. (2016). Experiencing Lifetime Domestic Violence: Associations with Mental Health and Stress Among Pregnant Women in Rural Bangladesh: The Minimat Randomized Trial. PLoS One, 11(12):e0168103.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Peedicayil, A., Sadowski, L. S., Jeyaseelan, L., Shankar, V., Jain, D., et al. (2004). Spousal Physical Violence Against Women During Pregnancy. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 111(7):682-687.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ntaganira, J., Muula, A. S., Masaisa, F., Dusabeyezu, F., Siziya, S., et al. (2008). Intimate Partner Violence Among Pregnant Women in Rwanda. BMC Women's Health, 8:1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shamu, S., Abrahams, N., Temmerman, M., Musekiwa, A., Zarowsky, C. (2011). A Systematic Review of African Studies on Intimate Partner Violence Against Pregnant Women: Prevalence and Risk Factors. PloS One, 6(3):e17591.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Elkhateeb, R., Abdelmeged, A., Ahmad, S., Mahran, A., Abdelzaher, W. Y., et al. (2021). Impact of Domestic Violence Against Pregnant Women in Minia Governorate, Egypt: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21:1-7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fisher, J., Tran, T. D., Biggs, B., Dang, T. H., Nguyen, T. T., et al. (2013). Intimate Partner Violence and Perinatal Common Mental Disorders Among Women in Rural Vietnam. International Health, 5(1):29-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Karaoglu, L., Celbis, O., Ercan, C., Ilgar, M., Pehlivan, E., et al. (2006). Physical, Emotional and Sexual Violence During Pregnancy in Malatya, Turkey. The European Journal of Public Health, 16(2):149-156.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shannon, L., Nash, S., Jackson, A. (2016). Examining Intimate Partner Violence and Health Factors Among Rural Appalachian Pregnant Women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(15):2622-2640.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Efetie, E. R., Salami, H. A. (2007). Domestic Violence on Pregnant Women in Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(4):379-382.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jamshidimanesh, M., Soleymani, M., Ebrahimi, E., Hosseini, F. (2013). Domestic Violence Against Pregnant Women in Iran. Journal of Family & Reproductive Health, 7(1):7.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Akrami, M. N. Z. (2006). Prevalence of Physical Violence Against Pregnant Women and Effects on Maternal and Birth Outcomes. Acta Medica Iranica, 95-100.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Edin, K. E., Högberg, U. (2002). Violence Against Pregnant Women Will Remain Hidden as Long as No Direct Questions Are Asked. Midwifery, 18(4):268-278.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rachana, C., Suraiya, K., Hisham, A. S., Abdulaziz, A. M., Hai, A. (2002). Prevalence and Complications of Physical Violence During Pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 103(1):26-29.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jahanfar, S., Howard, L. M., Medley, N. (2014). Interventions for Preventing or Reducing Domestic Violence Against Pregnant Women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McFarlane, J., Soeken, K., Wiist, W. (2000). An Evaluation of Interventions to Decrease Intimate Partner Violence to Pregnant Women. Public Health Nursing, 17(6):443-451.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pun, K. D., Infanti, J. J., Koju, R., Schei, B., Darj, E., et al. (2016). Community Perceptions on Domestic Violence Against Pregnant Women in Nepal: A Qualitative Study. Global Health Action, 9(1):31964.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mahenge, B., Likindikoki, S., Stöckl, H., Mbwambo, J. (2013). Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy and Associated Mental Health Symptoms Among Pregnant Women in Tanzania: A Cross-Sectional Study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 120(8):940-947.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Okour, A. M., Badarneh, R. (2011). Spousal Violence Against Pregnant Women from A Bedouin Community in Jordan. Journal of Women's Health, 20(12):1853-1859.

Publisher | Google Scholor