Case Report

Navigating the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges of Brenner Tumors: Insights from A Case Series

- Aidi Hadhami 1*

- Bannour Imene 1

- Ben Ali Yasmine 1

- Hammadi Jawaher 1

- Balsam Braiek 1

- Ben Fekih Ichrak 1

- Dorra Chiba 2

- Bannour Badra 1

- Moncef Mokni 2

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Farhat Hached University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia.

2Pathological Anatomy Department, Farhat Hached University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia.

*Corresponding Author: Aidi Hadhami, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Farhat Hached University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia.

Citation: Hadhami A., Imene B., Yasmine B.A., Jawaher H., Braiek B., et al. (2025). Navigating the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges of Brenner Tumors: Insights from A Case Series, Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology Research, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 4(1):1-8. DOI: 10.59657/2992-9725.brs.25.025

Copyright: © 2025 Aidi Hadhami, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 18, 2025 | Accepted: March 14, 2025 | Published: March 20, 2025

Abstract

Brenner tumors are relatively rare forms of ovarian fibroepithelial neoplasms and only account for 1-2% of all ovarian tumors. Because the vast majority of such tumors are benign, their diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment are straightforward. However, the malignant and proliferative forms which account only for 3 to 5% of Brenner tumors pose a significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. This paper has attempted to review the clinical and pathological aspect of this rarity in the perspective of four clinical cases and a review of the literature, focusing on the associated diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Surgical intervention remains the cornerstone of treatment.

Keywords: brenner tumor; ovarian neoplasm; borderline ovarian tumor; pelvic mass; CA125 marker

Introduction

Brenner tumors are ovarian tumors of transitional cells comprising of mature cells resembling urothelial cells forming nests in a fibromatous stroma which gives the tumor a distinct structure. Historically these tumors were first described by MacNaughton-Jones in 1898. Since their discovery these tumors have been studied for their various presentation. They exhibit a spectrum of behavior ranging from benign, borderline(intermediate) to malignant. Malignant Brenner tumors are among the rarest varieties. This rarity further complicates therapeutic strategies [1].

Case 1

Presentation and Imaging

Patient, T.B., a 72-year-old female with a history of longstanding hypertension and atrial fibrillation managed by antihypertensives and oral anticoagulants, presented to our outpatient department complaining of recurrent postmenopausal bleeding. The gynecological examination was unremarkable; the cervix appeared macroscopically normal, the uterus was of normal size, and no palpable adnexal masses was felt on bimanual examination. A pelvic ultrasound revealed a normal-sized uterus with a heterogeneous echotexture and a regular, 4-mm thick, vascularized endometrium on Doppler. A 7.5 x 6 cm solid-cystic mass was detected in the right ovary, with no internal septations and no blood flow on Doppler imaging (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Suprapubic ultrasound image of cystic ovary. this image shows thick, heterogeneous intracystic vegetation.

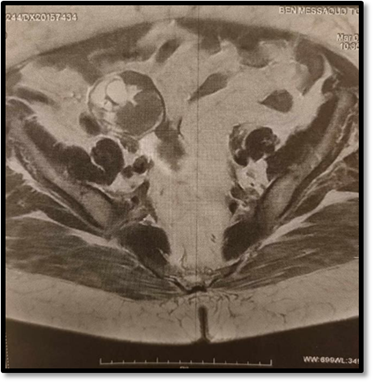

Following a team discussion, the decision was made to proceed with a pelvic MRI for a more detailed evaluation and characterization of the adnexal mass (Figure 2).

Figure 2: T2-ponderated MRI scan showing suspected ovarian cyst. this slide shows a heterogeneous solidocystic image.

MRI imaging revealed a thickening of the endometrium with myometrial invasion greater than 50%, along with a solid-cystic ovarian mass, raising the concern of a synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Carcinoma (SEOC). A right internal iliac lymph node enlargement was noted, but there was no evidence of lomboaortic lymphadenopathy.

Surgical Intervention and Findings

The patient underwent a combined diagnostic laparoscopy and simultaneous diagnostic hysteroscopy. A hypertrophic, proliferative, irregular, and heterogeneous endometrium with diffuse hyperemia throughout the uterine cavity. Both tubal ostia were clearly visualized. An endometrial biopsy was performed and submitted for histopathological evaluation. During laparoscopy, the abdominopelvic cavity appeared unremarkable. A small amount of yellowish ascitic fluid was noted, which was aspirated for cytological examination. The left adnexa appeared normal, while the right ovary contained a simple cyst with a smooth wall measuring 7 cm with no exophytic vegetations. During surgical manipulation an inadvertent rupture of the ovarian cyst occurred, releasing a greenish fluid that was also aspirated for cytological analysis. Cyst analysis revealed several fragile, translucent intralesional vegetations, prompting a right adnexectomy and an extensive peritoneal lavage.

Pathology

Histopathological examination identified a proliferative endometrial lining without cellular atypia. Distinctly, the ovarian mass was made of transitional (urothelial)-type epithelium, arranged in nests and clusters, embedded in fibrous stroma. The tumor cells exhibited mild nuclear atypia; a prominent nucleoli and nuclear grooves. Moreover, the stroma was fibrovascular with no evidence of capsular rupture. Additionally, the cystic areas were lined by transitional-type epithelium overlying a fibrovascular wall. The final diagnosis was a benign Brenner tumor of the right ovary, measuring 6.5 cm. The proposed therapeutic strategy involved clinical and ultrasound surveillance.

Case 2

Presentation and Imaging

Patient B.T., a 59-year-old postmenopausal female (G5P4A1) with no significant past medical history, presented with a two-year history of chronic pelvic pain, described as a sensation of heaviness. On physical exam, the patient was in good general condition. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender, the uterus was palpably enlarged, corresponding to approximately 12 weeks’ gestation. Hernial orifices were clear. On Gynecological exam a moist vaginal mucosa, a macroscopically normal cervix, and non-tender, mobile vaginal fornices were observed.

Further on pelvic ultrasound, an enlarged uterus (12 cm x 9 cm x 7 cm) with multiple fibroids with the largest measuring 5 cm. The endometrium lining was thin, and both ovaries were visualized with no anomalies were observed.

Surgical Intervention and Findings

Despite symptomatic treatment with first-line pain medication, there was no improvement. The patient opted for definitive surgical management and underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy without complications.

Pathology

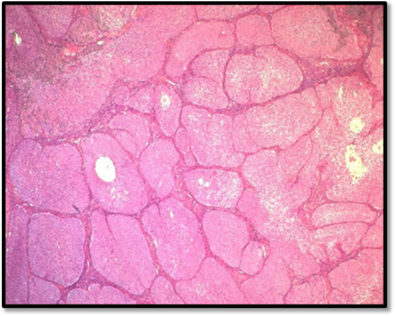

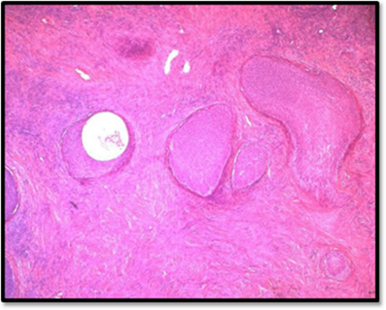

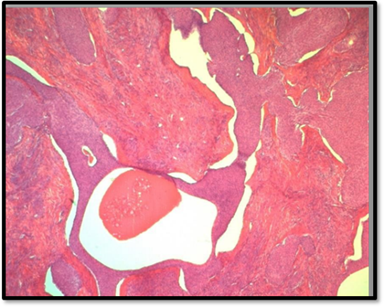

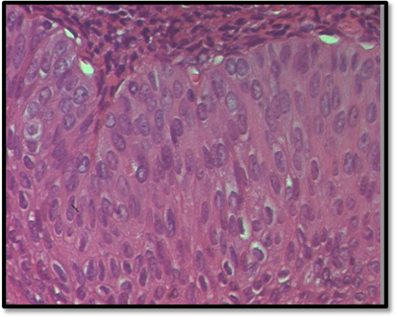

The final histopathological report revealed the presence of nine intramural and subserosal uterine leiomyomas with sizes ranging from 1 to 4.5 centimeters. While some of these leiomyomas exhibited aseptic necrosis, no evidence of malignancy was noted. Additionally, a benign ovarian tumor, measuring 0.6 centimeters at its largest diameter (measured on histological slide) was discovered. The tumor consisted of small, well-circumscribed nests of uniform cells with pale cytoplasm, finely nucleolated oval nuclei, and no evidence of mitosis or atypia. The stroma was mildly fibrous and resembled ovarian cortex. The contralateral adnexa were free of histological lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 3A: This microphotography shows that the benign Brennet Tumor is organized in nests or solid clusters (HE*10).

HE: Hematoxylin-Eosin

Figure 3B: Dense fibromatous stroma ressembling ovatian fibroma or thecoma (HE*10).

Figure 3C: Some nests show central cystic spaces where the lumina contains eosinophilic secretions and Irregular nests are scattered in dense hyalinized stroma (HE*10).

Figure 3D: The transitional cells have pale eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm, uniform ovoid nuclei which may have grooves, fine chromatin, and punctate nucleoli. There is no cytologic atypia and mitotic activity is not increased. (HE*40).

In light of these findings, a course of continued clinical monitoring was deemed appropriate. The patient remained free of symptoms.

Case 3

Presentation and Examination

Patient N.Z., a 71-year-old female, had been monitored for two years for cervical carcinosarcoma extending into the right parametrium (FIGO stage IIB). She initially received four cycles of taxol-carboplatin chemotherapy. She completed four cycles of taxol-carboplatin chemotherapy. Subsequent pelvic MRI demonstrated a stable cervical tumor and identified a 9 cm x 9 cm right adnexal cystic mass featuring with a thin wall and non-vascularized vegetations on Doppler imaging. No ascites was detected. Following a multidisciplinary discussion, an exploratory laparoscopy with possible bilateral adnexectomy was recommended (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Ultrasound image showing a pure anechogenic cystic mass with a thin wall and endocystic vegetation.

Surgical Intervention and Findings

During surgery, a large, thin-walled cystic mass originating from the right ovary was identified, with no evidence of intra-abdominal effusion or carcinomatous nodules. Macroscopically the mass was cystic, unilocular measuring 8.2 cm in its largest dimension, with a smooth external surface and no exophytic vegetations. Internally, a friable, translucent nodule measuring 1.6 cm was noted.

Pathology

Histopathological examination identified a tumor characterized by coalescing papillary structures lined by stratified epithelium resembling transitional cells (urothelium), with well-defined cell borders, clear cytoplasm, and round nuclei free of atypia. Mitoses were rare, and there was no evidence of stromal invasion. The remainder of the cyst wall, uninvolved by the tumor proliferation, was lined by regular urothelial-type epithelium. Addition, few well-circumscribed urothelial nests representing remnants of a benign Brenner tumor were identified. The definitive diagnosis was a borderline Brenner tumor of the right ovary, measuring 8.2 cm. Following the case review, the consensus was to proceed with adjuvant chemotherapy using Adriamycin monotherapy. The patient is currently undergoing chemotherapy cycles.

Case 4

Presentation and Imaging

Patient H.R., a 68-year-old female (G10P10A0), 13 years postmenopausal, presented to the outpatient department complaining of debilitating chronic pelvic pain and abdominal distension. On physical examination, she was noted to be morbidly obese (BMI: 37 kg/m²). The patient’s abdomen was distended by a firm, midline mass which palpably extended two fingerbreadths above the umbilicus. The hernial orifices were clear, and the gynecological exam revealed no abnormalities. Pelvic ultrasound revealed a multiloculated abdominopelvic mass, mixed solid-cystic composition, with thick septations and intralesional projections occupying the entire ultrasound field measuring greater than 20 cm. The mass was non-vascularized on Doppler, and its ovarian origin was difficult to ascertain. A subsequent abdominopelvic CT scan further revealed a suspicious cystic lesion, likely of ovarian origin, with a size exceeding 26 cm, raising concerns for a potentially malignant process.

Surgical Intervention and Findings

The multidisciplinary decision was to proceed with exploratory and therapeutic laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included a moderate volume of ascites, a healthy peritoneum, intact left adnexa, and an enlarged right ovary containing a massive, bilobed, solid-cystic mass with a thick wall and no exophytic vegetations, measuring approximately 30 cm. Bilateral adnexectomy was performed due to the clinical presentation.

Pathology

Macroscopic evaluation described a 33 cm x 17 cm multilocular mass with both a solid and a cystic appearance. The solid component was homogeneous, yellowish-white in color, while the cystic cavities were devoid of vegetations. Histological examination revealed a fibro-epithelial proliferation organized in nests and clusters of transitional cells. These cells were polyhedral in shape, with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and ovoid nuclei featuring a finely condensed chromatin and occasional grooves, with no evidence of atypia or mitotic activity. Some of the cystic areas were lined with mucinous epithelium, without abnormalities. The stroma was abundant, fibrous, and ovarian in type, with large hyalinized and some calcified areas. The right fallopian tube and left adnexa were free of any histological lesions. The therapeutic plan involved regular follow-up both clinical and ultrasound monitoring. Four years postoperatively, the patient remains asymptomatic.

Discussion

WHO [2] classifies ovarian tumors composed of cells resembling those of the urothelium as transitional cell tumors and estimates them to account for 1-2% of all ovarian tumors. They include Brenner tumors (benign, borderline, malignant) and transitional cell carcinoma (TCCs). Liao et al. [3] conducted a comparative study on p63 protein expression - a protein expressed in normal urothelium and most bladder TCCs-between two groups: one consisting of ovarian transitional cell tumors (benign Brenner, borderline Brenner, malignant Brenner, and TCC), and a second group with bladder TCC. The study found that while p63 expression by ovarian TCC was negative, it was highly positive in both benign and borderline Brenner tumors, as well as in bladder TCC. This study led to the conclusion that benign and borderline Brenner tumors show true urothelial differentiation. Moreover, low p63 expression suggests an involvement in the carcinogenesis process in Brenner tumors. Brenner tumors are uncommon, making up approximately 1-2% of all ovarian neoplasms. Most of these are benign. Only 2-5% are malignant Brenner tumors, which pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges [4]. These tumors primarily affect postmenopausal women typically between the ages of 40 and 70 years. In terms of symptoms, proliferative Brenner tumors do not vary much from other ovarian cysts, which are usually asymptomatic or manifest themselves by nonspecific signs like heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, or a vague sensation of heaviness. They generally present as slow-growing tumors, with the clinical manifestations appearing after an average period of four months. In some cases [5], Brenner tumors are diagnosed during an infertility study or along with pelvic endometriosis. Occasionally, acute complications like ovarian torsion or hemorrhage may require emergency surgical intervention [6]. Some Brenner tumors exhibit endocrine activity, secreting estrogen and may thus cause metrorrhagia or endometrial hyperplasia. In rare cases, they produce androgens, which result in virilization [7].

The most useful serum marker in the assessment of ovarian tumors is CA125, often used in association with CA19.9 and CEA for a more comprehensive evaluation. However, CA125 marker alone lacks the necessary sensitivity and specificity for valid screening, as its levels can be elevated with benign conditions like endometriosis, genital infections, and even ovulation. Nevertheless, an elevated CA125 serum level can help raise suspicion of malignancy, making it a valuable marker in certain cases [5]. The ultrasound and CT appearance of borderline Brenner tumors mimics that of malignant tumors, which generally appear as large, unilateral, mixed solid-cystic masses ranging between 8 and 30 cm, with intralesional vegetations. Malignant Brenner tumors may more often show hemorrhagic and necrotic changes [8]. MRI is generally not indicated, but it may be helpful for complex solid-cystic masses. This aids in the preoperative evaluation of malignancy and regional extension [8]. Histopathologically, borderline and malignant Brenner tumors are less well defined as compared to their benign counterparts making diagnosis especially challenging in intraoperative frozen sections [9]. In a case series conducted by Lawrence et al. involving 14 cases, proliferative Brenner tumors were found to be unilateral, large (average 20 cm), and of mixed solid-cystic nature. In 85% of the cases, multiple polypoid masses with a cauliflower appearance as described by P. Duvillard [9], were present within the cystic cavities. This distinctive macroscopic aspect could assist in guiding the frozen section examination, although its sensitivity is low, especially in borderline tumors (50%) [11]. Histologically, proliferative Brenner tumors exhibit epithelial proliferation similar to well-differentiated, non-invasive urothelial carcinomas, with small cysts lined by transitional epithelium and central fibrovascular core. Additionally, areas of mucinous or squamous metaplasia are often present [17] and the nuclei of the tumor cells usually display “coffee-bean” chromatin. Nuclear atypia and mitotic activity are minimal or absent. When Tumor necrosis occurs, it is generally focal [9,12,13]. Some experts reserve the term “proliferative Brenner tumor” only for tumors that are similar to grade I urothelial carcinomas, whereas others include grade II and III-like features as borderline tumors [9,17]. The last WHO classification has now separated the entity of transitional carcinomas from Brenner tumors, including a case as primary ovarian transitional cell carcinoma only in the absence of any benign or borderline Brenner tumor component [17].

Diagnosing Brenner tumor can be difficult due to their resemblance to urothelial carcinoma. Several studies have proposed the use of specific tumor markers to indicate urothelial differentiation. However, in the case of borderline Brenner tumor adequate sampling usually suffices to ensure the absence of significant cytological atypia, mitotic activity, or stromal invasion. The management of ovarian cysts is generally conservative: biopsy, cystectomy, or oophorectomy, especially in young females. However, if malignancy is suspected, a more radical approach may be indicated such as hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. For presumed benign organic cysts, laparoscopy has become the preferred surgical approach. Compared to laparotomy, it offers numerous advantages, including fewer complications related to wound healing and infection risks, less aesthetic damage, less postoperative pain, and reduced hospital stays [10]. Laparoscopy is generally indicated when all of the following criteria are met: cystic or dermoid content, fewer than three thin septations, a thin wall (lessthan 3 mm), absence of vegetations, and normal Doppler findings, with CA125 levels lessthan 35 U/mL. Although the upper limit of size for safe laparoscopic removal is still under debate, 10 cm is universally accepted as the threshold; however, several teams have been able to treat bigger-sized cysts with laparoscopy, provided appropriate safety precautions are taken [9]. In the absence of any concerning signs, laparoscopy is an appropriate treatment of ovarian cysts. Peritoneal cytology is routinely performed, and a frozen section of the specimen is done to confirm the benign nature. However, if suspicious elements are found preoperatively, a midline laparotomy conversion is advised, especially in suspicion of ovarian cancer with extra-ovarian involvement and/or suspicion of the possible cyst rupture during surgery. Several studies have shown that intraoperative rupture of malignant cyst is associated with a poor prognosis [14,15]. Determining preoperative criteria that would favor one procedure over another (laparoscopy vs laparotomy) is often quite difficult especially in intermediate cases such as those with isolated intracystic vegetation. Some authors, like Vergote et al. [15,16], emphasize the risk of dissemination and reserve the use of laparoscopy for those cases in which all criteria of benignity are fulfilled before the surgery. However, this approach would result in up to 40% of benign cysts being treated via laparotomy. Others, like Canis and co-authors [18], recommend starting with laparoscopy in cases where ultrasound suggests benign cysts, opting for laparotomy only for cases with malignancy index arising during the laparoscopic exploration. In all cases where laparoscopy is considered, the patient should always be informed of the possibility of conversion to an open procedure in advance. Although benign Brenner tumors have an excellent prognosis, malignant variants remain associated with uniformly poor outcomes despite aggressive therapeutic intervention. In contrast proliferative Brenner tumor variants appear to have a favorable prognosis, with no fatalities reported in the literature to date [9,17]. The vast majority of patients with proliferative Brenner tumors have been treated with radical surgery, whereas a few have been treated conservatively, since the nature of proliferative Brenner tumors are slow growing tumors and, therefore, may allow more conservative management especially in younger women [9]. In our case, alongside anexectomy, an omentectomy and prophylactic appendectomy were performed out of concern of incomplete treatment of as aggressive as ovarian carcinoma.

Conclusion

Brenner tumors are relatively rare neoplasms with characteristic histopathological features. Diagnosis is largely based on histology and immunohistochemical staining. In the absence of standardized therapeutic guidelines, surgical management remains the cornerstone of treatment.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to the patients for giving the permission to share this informative report.

Data Availability

No data is associated with this article.

References

- Bourhafour, M., Bourhafour, I., El Youbi, M. B., M'Rabti, H., Benjaafar, N., et al. (2013). Specificity of Sarcomatous Transformation in Recklinghaussen Disease: A Report of Two Cases and Review of The Literature. The Pan African Medical Journal, 15(1):73-73.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. (2003). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. WHO Classification of Tumours, 3rd Edition. IARC Press. 4.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Liao, X. Y., Xue, W. C., Shen, D. H., Ngan, H. Y. S., Siu, M. K., et al. (2007). P63 Expression in Ovarian Tumours: A Marker for Brenner Tumours but Not Transitional Cell Carcinomas. Histopathology, 51(4):477-483.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Young, R. H., Scully, R. E. (1988). Urothelial and Ovarian Carcinomas of Identical Cell Types: Problems in Interpretation A Report of Three Cases and Review of the Literature. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology, 7(3):197-211.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Van der Weiden, R. M. F., Gratama, S. (1987). Proliferative and Malignant Brenner Tumours (BT) and Their Differentiation from Metastatic Transitional Cell Carcinoma of The Bladder: A Case Report and Review of The Literature. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 26(3):251-260.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Raiga, J., Djafer, R., Benoit, B., Treisser, A. (2006). Management of Ovarian Cysts. Journal de Chirurgie, 143(5):278-284.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Roth, L. M., Dallenbach‐Hellweg, G., Czernobilsky, B. (1985). Ovarian Brenner Tumors. I. Metaplastic, Proliferating, And of Low Malignant Potential. Cancer, 56(3):582-591.

Publisher | Google Scholor - de Lima, G. R., de Lima, O. A., Baracat, E. C., Vasserman, J., Burnier Jr, M. (1989). Virilizing Brenner Tumor of The Ovary: Case Report. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 73(5 Part-2):895-898.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hirohashi, S., Iwasaki, S., Takewa, M., Ito, T., Ascher, S. M., et al. (2004). Borderline Brenner Tumor of the Ovary: MRI findings. Abdominal Imaging, 29(4):528-530.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Roth, L. M., Dallenbach‐Hellweg, G., Czernobilsky, B. (1985). Ovarian Brenner Tumors. I. Metaplastic, Proliferating, And of Low Malignant Potential. Cancer, 56(3):582-591.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Raiga, J., Djafer, R., Benoit, B., Treisser, A. (2006). Management of Ovarian Cysts. Journal de Chirurgie, 143(5):278-284.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vacher-Lavenu, M. C. (2001). Histologie des Kystes Bénins Borderline de L'ovaire et Dystrophies Sous-Péritonéales. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction, 30(S1):4S12-4S19.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Svenes, K. B., Eide, J. (1984). Proliferative Brenner Tumor or Ovarian Metastases? A Case Report. Cancer, 53(12):2692-2697.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tavassoli, F. A. (2003). WHO Classification of Tumors. Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon IRAC, 100-103.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Crouet, H., Heron, J. F. (1991). Dissemination of Ovarian Cancer During Celioscopic Surgery: A Real Danger. Presse Medicale (Paris, France: 1983), 20(35):1738-1739.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vergote, I., De Brabanter, J., Fyles, A., Bertelsen, K., Einhorn, N., et al. (2001). Prognostic Importance of Degree of Differentiation and Cyst Rupture in Stage I Invasive Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. The Lancet, 357(9251):176-182.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vergote, I. (2004). Role of Surgery in Ovarian Cancer: An Update. Acta Chirurgica Belgica, 104(3):246-256.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Canis, M., Mage, G., Pouly, J. L., Wattiez, A., Manhes, H., et al. (1994). Laparoscopic Diagnosis of Adnexal Cystic Masses: A 12-Year Experience with Long-Term Follow-Up. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 83(5):707-712.

Publisher | Google Scholor