Research Article

Magnitude of Depression and Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women Visiting Public and Private Health Facilities of Hawassa City Administration Sidama Region, Ethiopia

- Daniel Dere Deffecho *

- Desalegn Tsegaw

- Temesgen Tafesse Danshe

School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Science, Hawassa University Hawassa, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author: Daniel Dere Deffecho, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Science, Hawassa University Hawassa, Ethiopia.

Citation: Daniel D. Deffecho, Tsegaw D, Temesgen T. Danshe. (2025). Magnitude of Depression and Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women Visiting Public and Private Health Facilities of Hawassa City Administration Sidama Region, Ethiopia. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 5(4):1-12. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.25.088

Copyright: © 2025 Daniel Dere Deffecho, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: February 06, 2025 | Accepted: February 25, 2025 | Published: March 15, 2025

Abstract

Background: During pregnancy depression is the most common mental health problem. Now a time depression has been recognized as a global public health problem due to its severity, chronic nature, recurrence and its negative impact on the general health of women and the development of children. Aim of the study was to assess the magnitude of depression and associated factors among pregnant women visiting public and private health facilities in Hawassa city, Sidama Regional State, and Ethiopia.

Method: Institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Feb tot April 2022. Public and private health facilities were chosen proportionally using a simple random sampling technique. Data were collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire using the kobo toolbox. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Maternity social support score (MSSS) and threatening life event (TLE) were used to assess maternal depression, maternal social support and threatening life event respectively

Result: the magnitude of antenatal depression was 52.2 % (95%CI: 48, 56). Women visited public health facilities (AOR = 3.258; CI: 1.879, 5.650), urban residency (AOR = 0.253; CI: 0.101, 0.634), women with primary educational level (AOR = 0.436; CI: 0.231, 0.824), Regular follow up of antenatal care (AOR = 0.233; CI: 0.059, 0.926), Family planning utilization (AOR = 2.320; CI: 1.359, 3.962), primigravida (AOR = 0.062; CI: 0.005, 0.837), using of alcohol (AOR = 5.164; CI: 1.665, 16.018), and previous history of depression (AOR = 6.544; CI: 1, 101, 38.896) were significantly associated with antenatal depression.

Conclusion: the magnitude of depression among pregnant women visiting public and private health facilities in Hawassa was higher. Urban residency, visiting public health facilities, primary educational level of women, and alcohol usage were significantly associated with antenatal depression. In order to decrease the magnitude of antenatal depression concerned bodies should work on screening for depression, health education, and integration of service.

Keywords: depression; pregnant women; health facilities

Background

According to World Health Organization (WHO) depression is defined as a common mental disorder that presents with depressed mood, loss of interest or happiness, decreased energy, feelings of fault, or low self-confidence, troubled sleep or craving, and deprived attention [1]. Pregnancy is a transition to motherhood is often a very happy and exciting time. Unlikely not every woman feels this way. Major physical and psychological changes are expected in expecting mothers [2].This period is supposed to be one of the happiest times of a woman’s life, but for many women, this is a time of confusion, fear, stress, and depression [3]. Antenatal depression can be convoyed by signs and symptoms of low mood, fatigue, sleeplessness, lack of energy, insensibleness, irritability, and poor physical and cognitive functioning [4]. A study in developing countries suggests that maternal depression may be a risk factor for poor growth in young children. In addition to this depressive disorders often start at a young age; that reduce people functioning and often recurring. Because of this reason ,depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide in terms of total years lost due to disability [5]. Among the major element of reproductive health, mental health is the one with lesser attention and priority given especially in low and middle-income countries. Even there are many types of mental health during pregnancy, depression, is the most common one which accounts for around 12% of experiencing depression [6-8]. The risk of being vulnerable to depression is higher among the poor, homeless, the unemployed, persons with low education, victims of violence, migrants and refugees, indigenous populations, children and adolescents, abused women and the neglected elderly [9]. Amongst psychiatric complications that occur in pregnancy, depression is a prevalent mental health problem affecting about one in five women worldwide [10].

The reason to recognize depression as a global public health concern is due to its severity, chronic nature and recurrence as well as its impact on the health of women and development of children [11]. In this regard maternal depression becomes the immediate successor of infection and parasitic diseases burden in pregnant mothers [12].

Nationally more than one in ten pregnant women suffers from undetected depression. Myths about maternal mental health, including beliefs that maternal depression is rare, maternal mental health issue is not pertinent to MCH programs and in case if happened it can only be treated by specialists, and its incorporation into MCH programs is difficult [16, 20]. For most women pregnancy is a difficult time, and for those with the furthermost need for mental health care often have the minimum access to it. Also, during this time, both depression and poverty impacts on the woman, the fetus or infant, the family and the wider community [13]. pregnant women with depression are more likely to have negative views of themselves as parents, seeing themselves as having less personal control over their child’s development, and less able to positively influence their children [14]. Many studies were conducted globally [15, 16], regionally [17-19] and nationally [20-28]on antenatal depression but they overlook how much the magnitude and associated factors on mothers from private health facilities. That lacks the accorded minimum criteria to meet the representativeness of their findings. Studies from the same city were attentive for those women from public health facilities [25, 26]. We believe that this study helped us to realize how much the magnitude of depression is and identifying the associated factors to ease the overlooked threat in the life of the women, family, and community as a whole.

Methods

Study setting and Population

Hawassa, the capital city of Sidama Regional State, and is located in the south 275km from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The city has 8 administrative sub-cities having a population of 367,908 and comprises about 75,084 households The population is relatively young with 65 percentage being younger than 25 years of age and around 5.5 percentage older than 50years of age [29]. The city has 3 governmental Hospitals, 11 Governmental health Centers, and 13 health posts. Further, there are 4 hospitals, 2 Specialty clinics, and 44 medium clinics owned by private. Among the mentioned health institutions, three health centers and one General hospital from public health institutions and one general hospital and one specialty clinic from private health institutions were allocated randomly for the study.

Study design, period, and population

Institution based cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2022. The source population was pregnant women attending Antenatal care in Hawassa city health facilities (public and private) during the study period.

Study population Pregnant women attending Antenatal care in selected health facilities of Hawassa city administration. All pregnant women, irrespective of their trimester, who visited public and private health facilities of Hawassa city during the data collection period, were included in the study. T hose who was unable to listen or speak and with serious medical conditions and women who resided temporarily in the city (less than 6 month) were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula with the assumptions considering 35.4 percentage prevalence of antenatal depression in the previous study of Arbaminch [30]. considering the parameter of single population formula which are 95 percentage Confidence Interval, proportion of common mental disorder, d = Desired precision/the margin error (5 percentage), a design effect of 1.5 and 10 percentage non-response rate(nr) for this study, the final sample size of 579 participants is estimated.

n= =

= =351*1.5+10%nr = 579

=351*1.5+10%nr = 579

The multi-stage sampling method was used to select the study participants. The research was conducted at six health facilities selected from public and private health facilities in the Hawassa City administration; four public health facilities (three health centers and one hospital) from a total of 11 health centers three public hospitals and two private health facilities form a total of four private hospitals and two private specialty clinics using lottery method. The sample size was split between health institutions and proportionally to their ANC caseload. The sample size was correspondingly allocated. Then systematic random sampling technique was implemented using list prepared to select study participants. K will be calculated for each health facility.

Data collection tools and procedures

The Structured interview questionnaire and measurement scales were prepared in English and translated into Amharic and Sidaamu Afoo then back to English to check for its consistency. Kobo toolbox soft wear was used for data collection. Finally, the Amharic and Sidamic versions of the questionnaires were used to collect the data.

The questionnaire consisted of different parts: Questionnaires on demographic characteristics psychological factors and history of substance use, obstetric variables, current pregnancy variables, history of chronic illness, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Maternity social support score (MSSS), and Abuse assessment score.

EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), used to assess antenatal depression, a set of 10 screening questions each scored zero to three, the total score ranging from zero to 30 that can indicate whether symptoms are depression during pregnancy and in the year following the birth of a child too. EPDS was validated to identify antenatal and postpartum depression in many countries [18, 22, 25, 31, 32]. The tool showed specificity 77.0% and sensitivity of 84.6 percentage in Addis Ababa for postpartum use (Cronbach's Alpha =0.71) [33]. As the women who score higher have higher depressive symptoms. Comparable earlier studies were done in Ethiopia, women with scores≥13 were considered positive for antenatal depression screening whereas Less than 13 were considered negative for antenatal depression screening.

Maternity social support score (MSSS), which contains six items to assess social support. Social support questions reflect the affective aspects of relationships or the degree to which the subjects feel that they are loved and valued and the belief that they have help from people who care about them. It is a 4-point scale ranging from strongly agrees (higher score, coded as 4) to strongly disagree (coded as 1) higher scores mean more social support a scores range from 6 to a maximum score of 30. The cut of points to categorize MSSS looks, MSSS of 24–30 was grouped as high social support; 18–23 medium social support, and low social support were those below 18 [34, 35]. Twelve lists of threatening life events (TLE) were used to assess life stressors. Women who faced at least one stressful life event in the past six months were categorized as yes for threatening life events, and those without any stressful life events were grouped as no for threatening life events [36].

Data quality control

The quality was observed at different level and was include the following due emphasis in- order to capture the objective; by using KoBo toolbox softwear the structured interviewer administered questionnaire loaded on mobiles of data collectors was prepared in English and translated into Amharic and Sidaamu Afoo, was pretested prior to data collection, using 5 percentage of the sample size from population who will not be included in the study. Based on the finding of pretest, the necessary adjustment was made on, applicability with local context, the clarity of language, logical sequence of words, free of scientific terms and non-leading questions.

Study variables

Outcome variable: Pregnant women depression

Independent variables

Socio demographic factors (age, sex, educational level, economic status, marital status, ethnicity, and resident), Psychosocial factors support from husband, household decision-making status, community support, previous history of anxiety, and happiness by ANC service provided,Obstetric factors( parity, trimester, current obstetric complications, previous obstetric complications, need of current pregnancy, pattern of antenatal care, and history of family planning use),Lifestyle factors ( cigarette smoking, alcohol use, chat use and drug use)

Operational Definition

Antenatal depression: In this study the women was found to have EPDS total score ≥13 will be considered as depressed [33].

The previous history of anxiety: defined as an event of anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or attack, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive that occurred before the current antenatal visit.

Data processing and Analysis

Variables was coded and transformed as necessary. Data was checked, cleaned and edited for completeness and missing values. From Kobo tool box the data was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 for analysis. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to compute frequency, percentage and mean for independent and dependent variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to ascertain the association between explanatory variables and outcome variable. Variables with p-value Less than 0.2 in bivariate analysis (logistic regression) were candidate and transferred to multivariable logistic regression [25, 37]. In all analysis P-value Less than 0.05 was considered to declare statistical significance in multivariable logistic regression analysis. Model adequacy (Goodness-of-fit) was checked by Homer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Finally, the results were presented in texts, graphs, and tables.

Result

Socio-demographic factors

A total of 579 women participates in the study a response rate of 100%. Three hundred seventy (63.9%) were from public health facilities. The mean age of women was 28.9 + (4.586 SD) years. The sample consisted of 518(89.5%) respondents from urban residents (N=579.Nearly 270 (46.6%) of the respondents were Sidama ethnic group. Concerning religion nearly three in five 349 (60.28%) of the respondents were protestant, followed by orthodox 156 (26.94%) (Table 3).

Obstetric and gynecological factors

Among the pregnant women four hundred twenty-eight (73.9%) of respondents had a regular menstrual cycle. More than half of the respondents 404(69.8%) had a utilization history of contraceptives before the current pregnancy. Two among five 166 (41.1%) of those who used contraceptives had used Implants. Nearly eight among ten women 511(88.3%) had planned their pregnancy. About 174 (30.1%) women were primigravida. one hundred eighty-one (31.3%) pregnant women had a parity of less than 3, whereas 135(23.3%).

Magnitude of depression among pregnant women

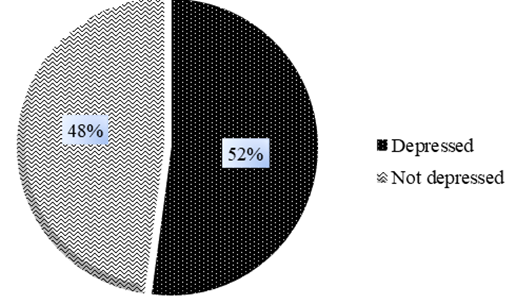

From a total of 579 respondents 302 (52.2%) had EPDS scores greater or equal to 13. The internal consistency of the EPDS tool was (Cronbach’s α = 0.87) acceptable. The study revealed that the overall magnitude of antenatal depression in this study was 52.2% (95% CI: 48%, 56%) (Figure3).

Factors Associated with antenatal depression

Out of the total variables found to be significantly associated with antenatal depression in the bivariate analysis; type of health facility where the women went for ANC, age of respondent, residency, marital status, ever married before, women's educational level, estimated family income, family planning utilization before current pregnancy, Intention of pregnancy, parity, gravidity, number of children, the trend of ANC follow up, history of depression, using alcohol were analyzed in multivariate analysis.

Table 1: Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of pregnant women attending public and private health facilities in Hawassa 2022.

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Age | Less than 20 | 18 | 3.1 |

| 20-30 | 324 | 56.0 | |

| >30 | 237 | 40.9 | |

| Resident | Urban | 518 | 89.5 |

| Rural | 61 | 10.5 | |

| Ethnicity | Sidama | 270 | 46.6 |

| Wolayta | 103 | 17.8 | |

| Oromia | 58 | 10.0 | |

| Amhara | 87 | 15.0 | |

| Other (specify) | 61 | 10.5 | |

| Religion | Protestant | 349 | 60.3 |

| Orthodox | 156 | 26.9 | |

| Muslim | 57 | 9.8 | |

| Other (specify) | 17 | 2.9 | |

| Marital status | Never married | 2 | 0.3 |

| Married or living together | 568 | 98.1 | |

| Divorced | 4 | 0.7 | |

| Widowed | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Ever married before | YES | 24 | 4.1 |

| NO | 555 | 95.9 | |

| Child from other marriage | YES | 10 | 1.7 |

| NO | 14 | 2.4 | |

| Went to school | YES | 567 | 97.9 |

| NO | 12 | 2.1 | |

| Women level of education | Unable to read and write | 12 | 2.1 |

| Able to read and write | 3 | 0.5 | |

| primary (1-8) | 101 | 17.4 | |

| attend grade 9-12 | 131 | 22.6 | |

| College and above | 332 | 57.3 | |

| Do husband have regular education? | YES | 572 | 98.8 |

| NO | 7 | 1.2 | |

| Husbands level of education | Unable to read and write | 7 | 1.2 |

| Able to read and write | 3 | 0.5 | |

| primary (1-8) | 51 | 8.8 | |

| attend grade 9-12 | 126 | 21.8 | |

| College and above | 392 | 67.7 | |

| Occupation of respondents | Government employee | 232 | 40.1 |

| Private employee | 88 | 15.2 | |

| Running personal business | 106 | 18.3 | |

| House wife | 105 | 18.1 | |

| Student | 28 | 4.8 | |

| Jobless | 20 | 3.5 | |

| Main occupation of husband of the respondents | Daily laborer | 46 | 7.9 |

| Farmer | 6 | 1.0 | |

| Trader / merchant | 136 | 23.5 | |

| Student | 8 | 1.4 | |

| Employed | 349 | 60.3 | |

| Other | 34 | 5.9 |

(*(Other ethnicity; Amaro, Dawro, Gamo, Gofa, Gurage, Hadiya, Kembata, Silte, and Somalia); *Other religion; Catholic, Only Jesus and Pagan). *Other occupation of husband; pastor, truck driver).

Figure 1: the magnitude of antenatal depression among pregnant women (n=579) visiting public and private health facilities in Hawassa city administration Sidama regional state Ethiopia, 2022.

Table 2: Obstetric factors among pregnant women attending public and private health facilities in Hawassa city administration 2022

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Pattern of menstrual cycle | Irregular | 151 | 26.1 |

| Regular | 428 | 73.9 | |

| Total | 579 | 100 | |

| Utilization of contraceptive before this pregnancy | YES | 404 | 69.8 |

| NO | 175 | 30.2 | |

| Total | 579 | 100 | |

| Kind of contraceptive used before this pregnancy | OCP | 10 | 2.5 |

| Dipo Provera | 113 | 28.0 | |

| Implant | 166 | 41.1 | |

| IUCD | 115 | 28.5 | |

| Total | 404 | 100 | |

| Is current pregnancy planned? | YES | 511 | 88.3 |

| NO | 68 | 11.7 | |

| Total | 579 | 100 | |

| Gravidity | Prim gravid | 174 | 30.1 |

| Multigravida | 405 | 69.9 | |

| Total | 579 | 100 | |

| Parity | Less than 3 | 181 | 31.3 |

| 3-5 | 262 | 45.3 | |

| >5 | 136 | 23.5 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 | |

| Number of live children | Less than 3 | 186 | 32.1 |

| 3-5 | 258 | 44.6 | |

| >5 | 135 | 23.3 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 | |

| Complication in previous pregnancy or labor | YES | 22 | 3.8 |

| NO | 557 | 96.2 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 | |

| Complication faced in the previous pregnancy | Abortion | 2 | 9.09 |

| Preterm birth | 8 | 36.36 | |

| still birth | 8 | 36.36 | |

| other | 4 | 18.18 | |

| Total | 22 | 100 | |

| Intention of pregnancy | Intended | 37 | 6.4 |

| Unintended | 542 | 93.6 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 | |

| Trimester | First trimester | 77 | 13.3 |

| Second trimester | 266 | 45.9 | |

| Third trimester | 236 | 40.8 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 | |

| ANC follow up in current pregnanacy | YES | 446 | 77.0 |

| NO | 133 | 23.0 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 | |

| How you follow ANC? (trend of ANC follow up) | Regularly | 429 | 96.2 |

| Irregularly | 17 | 3.8 | |

| Total | 446 | 100 | |

| Complication in current pregnancy | YES | 39 | 6.7 |

| NO | 540 | 93.3 | |

| Total | 579 | 100.0 |

Table 3: Psycisocial factors of womens among pregnant women attending public and private health facilities in Hawassa city administration 2022

| Variables | Category

| Antenatal depression | Total | Percent % | |

| NO | YES | ||||

| Maternal social support | High | 24 | 22 | 46 | 7.9 |

| Medium | 211 | 218 | 429 | 74.1 | |

| Low | 42 | 62 | 104 | 18.0 | |

| Threatening life event (TLE) | Present | 6 | 300 | 306 | 52.8 |

| Absent | 271 | 2 | 273 | 47.2 | |

| Partner’s feeling on current pregnancy | Happy | 274 | 293 | 567 | 97.9 |

| Unhappy | 3 | 9 | 12 | 2.1 | |

| Husbands desire of sex of the baby | Male | 61 | 64 | 125 | 21.6 |

| Female | 25 | 41 | 66 | 11.4 | |

| Neutral | 191 | 197 | 388 | 67.0 | |

| Baby’s father support | Poor | 0 | 9 | 9 | 1.6 |

| Good | 277 | 293 | 570 | 98.4 | |

Table 4: Factors associated with depression among pregnant women attending public and private health facilities in Hawassa city administration, Sidama regional state, Ethiopia 2022.

| Variables | Antenatal depression | COR(95%CI) | AOR(95%CI) | ||

| Yes | No | ||||

| Health facility | public | 211 | 159 | 1.771(1.222,2.423)* | 3.258 (1.879,5.650)** |

| private | 91 | 277 | 1 | 1 | |

| Age | Less than 20 | 14 | 4 | 2.511(0.802,7.857) | 0.362 (0.014,9.051) |

| 20-30 | 150 | 174 | 0.618(0.441,0.867)* | 0.735(0.459,1.176) | |

| > 30 | 99 | 138 | 1 | 1 | |

| Residency | Urban | 252 | 266 | 0.208(0.106,0.409)* | 0.253(0.101,0.634)** |

| Rural | 50 | 11 | 1 | 1 | |

| Marital status | Not married | 10 | 1 | 9.452(1.202,74.324)* | 3.792(0.123,117.062) |

| Married | 292 | 276 | 1 | 1 | |

| Unable to read and write | 8 | 4 | 2.256(0.66,7.638) | 0.644(0.085,4.882) | |

| Primary y (1-8) | 55 | 46 | 1.349(0.863,2.109) | 0.436(0.231,0.824)** | |

| attend grade 9-12 | 80 | 51 | 1.770(1.172,2.672)* | 0.929(0.506,1.704) | |

| College and above | 156 | 176 | 1 | 1 | |

| Estimated family income | Less than 4000 | 61 | 35 | 1.880(1.134,3.118)* | 1.814(0.838,3.930) |

| 4000-10000 | 152 | 146 | 1.123(0.778,1.621) | 1.367(0.827,2.257) | |

| > 10000 | 89 | 96 | 1 | 1 | |

| FP before current pregnancy | yes | 179 | 225 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 123 | 52 | 2.973(2.035,4.343)* | 2.320(1.359,3.962)** | |

| Intention of pregnancy | Intended | 256 | 255 | 0.480(0.281,0.821)* | 1.244(0.558,2.777) |

| Un intended | 46 | 22 | 1 | 1 | |

| Parity | Less than 3 | 80 | 101 | 0.522(0.332,0.819)* | 6.236(0.117,332.047) |

| 03-May | 140 | 122 | 0.756(0.496,1.151) | 0.516(0.147,1.810) | |

| >5 | 82 | 54 | 1 | 1 | |

| Number of child | Less than 3 | 83 | 103 | 0.551(0.351,0.865)* | 0.332(0.016,7.088) |

| 03-May | 140 | 120 | 0.797(0.522,1.218) | 1.332(0.380,4.663) | |

| >5 | 79 | 54 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gravidity | Prim gravid | 76 | 98 | 0.614(0.429,0.879)* | 0.062(0.005,0.837)** |

| Multigravida | 226 | 179 | 1 | 1 | |

| Trend of ANC follow up | Regularly | 210 | 219 | 0.295(0.095,0.919)* | 0.233(0.059,0.926)** |

| Irregularly | 13 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| History of depression | Yes | 14 | 2 | 6.684(1.505,29.681)* | 6.544(1.101,38.896)** |

| No | 288 | 275 | 1 | 1 | |

| Using alcohol | Yes | 27 | 9 | 2.924(1.350,6.333)* | 5.164(1.665,16.018)** |

| No | 275 | 268 | 1 | 1 | |

Note: *p Less than 0.05, **p Less than 0.01

Discussion

The magnitude of AND among pregnant women who came to public and private health facilities in the current study was 52.2% (95% CI: 48%, 56%). The finding was higher as compared with a systematic review and a systematic and meta-analysis studies done in Africa which were 11.3%,26.3% respectively [38, 39]. On the other hand this figure was substantially higher when compared to other similar studies done in Ethiopian regions which had a low magnitude of antenatal depression which ranges between 11.8% - 35.8%, as compared with the current study; the study done in Hawassa 21.5% [20] , North West Ethiopia (24.45%) [40], Addis Ababa (24.94%)[41], Debretabore (11.8%) [31], South East Ethiopia (35.8%) [42] , West shoa Zone Oromia (32.3%)[43], Arbaminch (35.4%) [25], Wolayta Sodo (16.3%) [22],and Gurage Zone (27.6%)[21]. The discrepancy might be due to methodological differences between studies & study settings (institution vs community-based). The other variations could be attributed to the difference in health facilities selection (public vs private) and the tool used to measure the data to screen depression among pregnant women. .The other important explanation might be that in this study EPDS was used while others used patient health questionnaire item nine (PHQ9), and self-reporting questionaries’ (SRQ) [39]. Antenatal depression was significantly higher among participants who visited public health facilities. This is in line with the finding from study conducted in Poland. The study agreed upon this point that there was a huge gap between care and quality of service between public and private health facilities. This might be because of a more attractive and caring environment in the private health facilities.

On the other hand, pregnant women who were from rural residency were more likely to experience antenatal depression. This is in line with the finding from the study conducted in United Kingdome, and Pakistan [44, 45]. Also the study from India reviled that being an urban resident may tends to increase by five times the chance of the women to being depressed[16] .This might be due to different angle life exposures which enable the women to have appropriate copping mechanism towards depression. Being rural or urban resident by itself may not be the cause for the experience of depression, instead that may be the problem with planning, and managing things appropriately. Furthermore, women who have an educational level of primary education were less likely to experience depression during their pregnancy than those who have an educational level of college and above. Unlike other studies the primary level of education was found to be protective against depression in this study [16, 18, 46].

The present study also found that pregnant women who had irregular trend of ANC visit were 23% more likely to experience antenatal depression as compared to those women having regular ANC follow up trend. This finding was in agreement with the systematic review conducted in Ethiopia [47]. This might be because having not regular ANC follow up may lead the women to being worried about what is new should be known about the fetus and herself secondary to missed appointments. In this, study using family planning before the current pregnancy was found to be significant predictor of antenatal depression. This is in line with finding from study conducted in wolayta Sodo [22].This might be because women who use family planning were more likely to plan their pregnancy and that could help to decrease the chance of being depressed .

In this study, women who gave birth for the first time were more likely to develop postnatal depression than those who gave birth more one times. This finding is consistent with a study done Arbaminch [25], Jima [48], Nekemte [49], and Vietnam [50]. But studies from south west Ethiopia [51], mizan aman (52),and India [53] were against this finding . This might be related to the lack of experience in parenthood and increased fear related to pregnancy and its outcome. Having previous history of depression has significant association with antenatal depression. Women who have previous history of depression were 6.5 times more likely to experience antenatal depression than women without previous history of depression. This finding was in agreement with other study findings [20, 23, 24, 31, 32, 39]. This may be as a result of hormonal changes during pregnancy might precipitate previous depression or their psycho-social context may make them vulnerable to recurrent depression. Increased odds of antenatal depression among pregnant women who drank alcohol compared to those who didn’t drink alcohol were also detected. This finding is in line with the studies conducted in Nekemte town, East Wollega zone, west Ethiopia and the study conducted in India and Australia [15, 16, 49, 54]. This might be due to the fact that alcohol use during the antenatal period could affect women’s emotions and behaviors, which could be responsible for the development of antenatal depression (Table 3).

Limitations of the study

Among the limitations, the first limitation of this study was using a cross-sectional study design, which impedes the research from establishing the cause and relationship between independent and outcome variables, which called to be ‘the chicken egg dilemma of is the chicken-egg dilemma between independent and the outcome variables.

Because of using an institutional study design, this study fails to address those women who did not visit health institutions. Also, the tools used to assess abuse, social support, and threatening life event were not validated in Ethiopia. And also, this study cannot assess hormonal and genetic factors that may essentially determine antenatal depression. There was also hassle during translating questionnaires and on different scales from the original language to the local languages. We were challenged and even failed to get the correct or good synonym meaning.

There was a time-bound variation between tools, and the possibility of multiple instructions in between interviews which might cause distraction. In addition to this, the information’s asked to women required to remember events that happened as back as 12 month and or six months that may cause the possibility of recall bias, interview bias, and miss interpretation of events were among the potential limitations of the study.

Conclusion

This study found that 52.2% of respondents had antenatal depression, which is significantly a highest value. It also identifies the presumed risk factors; socio-demographic factors like health facility type, primary educational level of the women and rural residency, family planning utilization before current pregnancy, primigravida women, irregular trend of ANC follow up were associated with antenatal depression. Similarly, women who used alcohol during pregnancy, previous history of depression had a higher probability of being depressed at antenatal period. Nearly one in two pregnant women visiting public and private health facilities in Hawassa city administration had antenatal depression. The magnitude of antenatal depression in this population was relatively higher than in studies reported in Ethiopia. Being from urban residency, visiting public health facilities, primary educational level of women, using of alcohol during pregnancy, prim gravidity, family planning utilization, irregular rend of ANC follow up, and previous history of depression were significantly associated with antenatal depression in this study. Early detection and appropriate intervention, screening for depression during routine ANC setting might be considered supported by integration of family planning and mental health services.

Abbreviations

AAS: Abuse Assessment Screen, AIDS: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. ANC: Ante Natal Care. CPMD: Common Perinatal Mental Disorders, GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder, HIV: Human Immune Virus, MDD: Major Depressive Disorder, MSSS: Maternity Social Support Score, OCD: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, SPSS: Statistical Package Social Science, WHO: World health organization

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences of Hawassa University before commencing data collection (Ref. No: IRB/234/15). An official letter of permission was obtained from the Department of Public Health to the respective district health office. Informed written permission was also obtained from the Hawassa admiration health office. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

The fnancial aid of this thesis was obtained Hawassa College health science with specific grant numbers HSC/10123/15. Daniel Dere is author who received award. The funded agency did not take part in the thesis design, data collection, and manuscript preparation process.

Authors’ contributions

DDD- Involved in initiation of the research question, prepared the research proposal, carried out the research, did the data entry and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. TTD- conducted edition, advising, cooperatively prepared research tools with PI, and revised the manuscript. DT- conducted edition, advising, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the Hawassa University, School of Public Health for approval of ethical clearance. The authors are also very grateful for data collectors.

References

- (2008). World Health O, World Organization of Family D. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Excellence Nifhac. (2020). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance.

Publisher | Google Scholor - American Pregnancy A. Pregnancy Questions?.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dadi AF, Miller ER, Woodman R, Bisetegn TA, Mwanri L. (2020). Antenatal depression and its potential causal mechanisms among pregnant mothers in Gondar town: application of structural equation model. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1):168.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Marcus M YM, Ommeren Mv, Chisholm D, Saxena S. W orld Health Organization, Depression a global public health concern Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse 2012.

Publisher | Google Scholor - NICE. (2014). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. NICE guidline.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2015). Federal Democratic Republic Ethiopia Ministry of Health NMHS, Australia.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ethiopia MohFRo. National mental health strategy 2012/13 - 2015/16. 2013.

Publisher | Google Scholor - W.H.O. (2003). Investing in mental health. In: Dependence DoMHaS, editor. World Health Organization.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. (2012). Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(2):139g-149g.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mathers CD, Loncar D. (2006). Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS medicine, 3(11):e442.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rahman A, Surkan PJ, Cayetano CE, Rwagatare P, Dickson KE. (2013). Grand Challenges: Integrating Maternal Mental Health into Maternal and Child Health Programmes. PLoS medicine,10(5):e1001442.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Flisher AJ. (2013). Maternal Mental Health A handbook for health workers. 3rd, editor. south africa.

Publisher | Google Scholor - GoodmanSHetal. (1993). Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: The Role Functioning Scale. Community Mental Health Journal, 29.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Melo EF, Cecatti JG, Pacagnella RC, Leite DFB, Vulcani DE, Makuch MY. (2012). The prevalence of perinatal depression and its associated factors in two different settings in Brazil. Journal of affective disorders, 136(3):1204-1208.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nisarga V, Anupama M, Madhu KN. (2022). Social and obstetric risk factors of antenatal depression: A cross-sectional study from South-India. Asian J Psychiatr, 72:103063.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kaiyo-Utete M, Dambi JM, Chingono A, Mazhandu FSM, Madziro-Ruwizhu TB, Henderson C, et al. Antenatal depression: an examination of prevalence and its associated factors among pregnant women attending Harare polyclinics. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1):197.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Matiko Mwitaetal. (2021). The magnitude and determinants of antepartum depression among women attending antenatal clinic at a tertiary hospital, in Mwanza Tanzania; a cross-sectionalstudy. Pan African Medical Journal, 38(258).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gebregziabher NK, Netsereab TB, Fessaha YG, Alaza FA, Ghebrehiwet NK, Sium AH. (2020). Prevalence and associated factors of postpartum depression among postpartum mothers in central region, Eritrea: a health facility based survey. BMC Public Health, 20(1):1614.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Duko B, Ayano G, Bedaso A. (2019). Depression among pregnant women and associated factors in Hawassa city, Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health, 16(1):25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shitu Ayen S, Alemayehu S, Tamene F. (2020). Antepartum Depression and Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women Attending ANC Clinics in Gurage Zone Public Health Institutions, SNNPR, Ethiopia, 2019. Psychology research and behavior management, 13:1365-1372.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Chuma BT, Sagaro GG, Astawesegn FH. (2020). Magnitude and Predictors of Antenatal Depression among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care in Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia: Facility-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Depression research and treatment, 6718342.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Keliyo ET, Jibril MK, Wodajo GT. (2021). Prevalence of Antenatal Depression and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care at Health Institutions of Faafan Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Depression research and treatment, 2523789.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gebremichael G, Yihune M, Ajema D, Haftu D, Gedamu G. (2018). Perinatal Depression and Associated Factors among Mothers in Southern Ethiopia: Evidence from Arba Minch Zuria Health and Demographic Surveillance Site. Psychiatry Journal, 7930684.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beketie ED, Kahsay HB, Nigussie FG, Tafese WT. (2021). Magnitude and associated factors of antenatal depression among mothers attending antenatal care in Arba Minch town, Ethiopia, 2018. PLoS One, 16(12):e0260691.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tilahun B, Mossie TB, Sibhatu AK, Dargie A, Ayele AD. (2017). Prevalence of Antenatal Depressive Symptoms and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in Maichew , North Ethiopia : An Institution Based Study. Ethiop J Heal Sci, 27.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beyene GM, Azale T, Gelaye KA, Ayele TA. (2021). Depression remains a neglected public health problem among pregnant women in Northwest Ethiopia. Archives of public health Archives belges de sante publique, 79(1):132.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tefera TB, Erena AN, Kuti KA, Hussen MA. (2015). Perinatal depression and associated factors among reproductive aged group women at Goba and Robe Town of Bale Zone, Oromia Region, South East Ethiopia. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology, 1(1):12.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2007). Central Statistical Agency Ethiopia. population and housing census of Ethiopia. Administrative report. In: Agency CS, editor. Addis Ababa.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Beketie ED KH, Nigussie FG, TafeseW. (2018). Magnitude and associated factors of antenatal depression among mothers attending antenatal care in Arba Minch town, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 16(2).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bisetegn TA MG, Muche T. (2016). Prevalence and Predictors of Depression among Pregnant Women in Debretabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 11(9).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mengistu Lodebo DB, Samuel Abdu, and Tadele Yohannes. (2018). Magnitude of Antenatal Depression and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in West Badewacho Woreda, Hadiyya Zone, South Ethiopia: Community Based Cross Sectional Study. Hindawi, 2020(2950536).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Tesfaye M, Hanlon C, Wondimagegn D, Alem A. (2010). Detecting postnatal common mental disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Kessler Scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(1):102-108.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dibaba Y FM, Hindin MJ. (2013). The association of unwanted pregnancy and social support withdepressive symptoms in pregnancy: evidence from ruralSouthwestern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(135).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Corrigan CP, Kwasky AN, Groh CJ. (2015). Social Support, Postpartum Depression, and Professional Assistance: A Survey of Mothers in the Midwestern United States. J Perinat Educ, 24(1):48-60.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bisetegn TelakeAzale, Mihretie Getnet, Muche Tefera. (2016). Prevalence and Predictors of Depression among Pregnant Women in Debretabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia. PLOS ONE, 11.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hosmer Jr DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. (2013). Applied logistic regression: John Wiley & Sons.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Emily C. Baron CH, Sumaya Mall, Simone Honikman, Erica Breuer, Tasneem Kathree, Nagendra P. Luitel, Juliet Nakku, Crick Lund, Girmay Medhin, Vikram Patel, Inge Petersen,Sanjay Shrivastava and Mark Tomlinson,. (2016). Maternal mental health in primary care in five low- and middle-income countries: a situational analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 16(53).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dadi AF, Wolde HF, Baraki AG, Akalu TY. (2020). Epidemiology of antenatal depression in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1):251.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Habtamu Belete A, Alemayehu Assega M, Alemu Abajobir A, Abebe Belay Y, Kassahun Tariku M. (2019). Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated factors among pregnant women in Aneded woreda, North West Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC research notes, 12(1):713.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Biratu A HD. (2015). Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Reproductive health, 12(99).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Woldetsadik AM, Ayele AN, Roba AE, Haile GF, Mubashir K. (2019). Prevalence of common mental disorder and associated factors among pregnant women in South-East Ethiopia, 2017: a community based cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health, 16(1):173.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Takele Tiki KT, and Bereket Duko. (2018). Prevalence and factors associated with depression among pregnant mothers in the West Shoa zone, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Annals of General Psychiatry, 19(24).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mechelli A. (2019). Cities increase your risk of depression, anxiety and psychosis – but bring mental health benefits too.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Atif M, Halaki M, Raynes-Greenow C, Chow C-M. (2021). Perinatal depression in Pakistan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Birth, 48(2):149-163.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Nasreen HE KZ, Forsell Y, Edhborg M. (2011). Prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: a population based study in rural Bangladesh. BMC Womens Health, 11(22).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ayano G, Tesfaw G, Shumet S. (2019). Prevalence and determinants of antenatal depression in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 14(2):e0211764.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Alenko A DS, Girma S. (2020). Sociodemographic and Obstetric Determinants of Antenatal Depression in Jimma Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia: Facility Based Case-Control Study. Int J Womens Health, 12:557-565.

Publisher | Google Scholor - AbadigaM. (2019). Magnitude andassociated factors of postpartum depressionamong women in Nekemte town, East Wollega zone, west Ethiopia,A community-basedstudy. PLoS ONE, 14(11).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Do TKL, Nguyen TTH, Pham TTH. (2018). Postpartum Depression and Risk Factors among Vietnamese Women. BioMed Research International, 4028913.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kerie S, Menberu M, Niguse W. (2018). Prevalence and associated factors of postpartum depression in Southwest, Ethiopia, 2017: a cross-sectional study. BMC research notes, 11(1):623.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Toru T, Chemir F, Anand S. (2018). Magnitude of postpartum depression and associated factors among women in Mizan Aman town, Bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1):442.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Anamika Agarwala PAR, Prakash Narayanan. (2018). Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among mothers in the rural areas of Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, India: A cross-sectional study. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 7(2019):342-345.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zhao L, McCauley K, Sheeran L. (2017). The interaction of pregnancy, substance use and mental illness on birthing outcomes in Australia. Midwifery, 54:81-88.

Publisher | Google Scholor