Research Article

Health Related Quality of Life of Children and Teenager (Age group- 8-18 Years) During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study in Odisha

1Department of Statistics, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, Odisha, India.

2Sidhi Vinayak Vidya Mandir, Titilagarh, Balangir, India.

*Corresponding Author: Mahesh Kumar Panda, Department of Statistics, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, Odisha, India.

Citation: Mahesh K Panda, Bhoi M. (2023). Health Related Quality of Life of Children and Teenager (Age group- 8-18 Years) During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study in Odisha, Journal of Genetic Research and Disorders, BRS Publishers. 1(1); DOI: 10.59657/jgrd.brs.23.001

Copyright: © 2023 Mahesh Kumar Panda, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: May 29, 2023 | Accepted: June 12, 2023 | Published: June 19, 2023

Abstract

Background: There are confined facts on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) associated with Indian youngsters. The goal of this examines turned into to assemble a generic HRQOL reference for youngster’s elderly 8-18 year from a community setting. The final decade has evidenced a dramatic growth with inside the improvement and usage of pediatric health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures so that it will enhance pediatric affected person fitness and health and decide the cost of healthcare services.

Methods: The pattern analyzed represented infant self-report age data on 202 youngsters ages 8 to 18 years from the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales Database. The study was a cross-sectional survey. An overall of 202 youngsters/teens with inside the age group of 8-18 year had been enrolled. The records contained infant self-record and parent proxy record from wholesome youngsters and their mother and father/caretakers. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL4.0) Generic Core Scale became used to accumulate HRQOL records. Questionnaires had been self-administered for mother and father and youngsters aged 8-18 year.

Results: The mean HRQOL total scores from child self-report and parent proxy report were 56.73±13.11 and 55.83±12.70 respectively, for children aged 8-18 yr. social functioning had the highest scores and School functioning had the lowest scores for the entire sample. The mean values for HRQOL in the current study were significantly different from the reference study for both child (56.73 vs 87.39 and 83.91, P<0.001) and parent proxy reports (55.83 vs 90.03 and 82.29, P<0.001) when compared between children aged 8-18 yr.

Conclusion: The study supplied reference values for HRQOL in youngsters and teens from Odisha, India, that regarded to be different from present global reference. It appears that the health-related quality of life of youngsters and teens throughout covid-19 become very negative as evaluate to earlier than covid-19. Similar research wants to be carried out in different parts of India to generate a country-precise HRQOL reference for Indian youngsters.

Keywords: adolescents, children; health-related quality of life; pediatric quality of life inventory; COVID-19

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic probably started from Wuhan, Hubli, China while the World Health Organization (WHO) got information about it on December 31, 2020. They received information about on unidentified ethology. The epidemic was officially named COVID-19 on February 11, 2020. It was acknowledging as an infectious disease which resulting in public health emergency, it quickly spread with in China and after spreading in China it moves to further 24 countries which are situated geographically between 42.9370840N-75.61070E (Anderson et al,2020).

In this new learning paradigm, teachers are working as content curators, and parents also stepping in as proctors for learning of children. Parents have a crucial role in the education of school children since it can be perplexing for those who are using online learning platforms for the first time. The success of virtual schooling considerably depends upon the self-motivation of the student, and parents’ engagement with the children. Parents support the child by building the learning and encourage them during online learning. In a developing country like India, all the children do not have the required skills and resources to cope up with this digital shift. This sudden shift from the classroom has given rise to many concerns such as, for how long will these online modes of teaching and learning will continue and what will be the impact of such a shift on children’s as well as parent’s mental, physical and social health (Gavin et al. 2020). While certain people are of the belief that the impromptu and swift move to online learning, with insufficient training and less preparation, may aggregate poor growth of a child thereby resulting in various kinds of physical as well as mental health issues and challenges, others think that this new way of education will surface, with significant benefits (Bhat et al. 2020; Raiet al. 2004; Kumari et al. 2020).

The term "quality of life" (QOL) refers to a general sense of well-being that encompasses numerous characteristics of enjoyment and contentment with life as a whole. The idea of health-related QOL (HRQOL) and its determinants has grown to include those parts of overall QOL that have been proved to have an impact on health, whether physical or mental. Self-reported health status is a strong predictor of mortality and morbidity in the future (J Health Soc Behav et.al.1997).

Several techniques for measuring HRQOL in childhood and adolescence are currently available4. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL 4.0) by Varni et al is the most widely used version for pediatric and adolescent HRQOL. The PedsQL 4.0 includes a generic core scale as well as disease-specific measures for cardiac sickness, asthma, cancer, and rheumatologic illnesses. (Varni JW et.al., 2007). This tool's data on pediatric HRQOL has been used to assess HRQOL in a number of pediatric illnesses/conditions, including asthma, cardiac sickness, cancer, cerebral palsy, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, rheumatological disorders, and psychiatric illnesses. These reference data were compiled from children aged 2 to 18 years old in California, USA, and used globally. The idea of QOL is likely to be influenced by a variety of cultural, societal, religious, ethnic, and regional influences, and children and parents from various communities may experience it differently (Varni JW et.al., 2005/ Banerjee et.al, 2010). The mean overall HRQOL score indicated in a study done among children from the United States was 83.8 (12.7), whereas a study done among Thalassemia children from Thailand recorded a score of 76.7 (11.4), both from kid self-reports7,8. According to parent reports, another study of Palestinian preschool children from war zones indicated that their total HRQOL score was 62 (Kumar N et.al. ,2012).

HRQOL was measured in all three investigations using PedsQL 4.0. HRQOL data from normal and atypical children in the Indian subcontinent has also been collected using PedsQL. Using self-reports, Awasthi et.al. found that adolescents aged 10 to 19 years old studying in Hindi and English medium schools had a mean HRQOL of 73.8 (10.4) and 75.3 (11.9), respectively. Banerjee et.al. found that children aged 8-12 years old had a mean HRQOL of 75.8 (14.9) for self-report and 70.3 (21.2) for parent proxy report. This heterogeneity may confuse the benchmarking process, which compares children/adolescents from a specific community to a single dataset that may or may not accurately reflect them. The treatment of children with acute and chronic medical disorders has been transformed thanks to rapid advances in medicine. In order to evaluate the influence of these disorders on total QOL, HRQOL must be measured in infancy and adolescence. The physical, psychological (emotional and cognitive), and social health sub-domains of HRQOL instruments now available for children and adolescents are multi-dimensional.

The major goal of this study was to create a generic HRQOL reference nomogram using the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales for children aged 8 to 18 years in Odisha, India. The secondary goals were to see if the generic core scales were feasible and reliable in the Indian context. The null hypothesis was that the means of total HRQOL as measured by parent reports using PedsQL 4.0 were not substantially different from the reference nomogram and the one produced from research data. Because of its high levels of reliability, validity, sensitivity, responsiveness, and feasibility, the PedsQL test was utilized to assess HRQOL (Varni JW et.al. Med Care 2001 / Ambul Pediatr et.al. 2003).

Research Methodology

Study area

Odisha is a state belongs to world’s 2nd largest populated country India. For this research we take Odisha as our study area. And we take all samples from all the adults of Odisha for analysis. Odisha is a costal state which is near the Bay of Bengal. The nearest states to Odisha are Jharkhand, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh. The state Odisha has its total area up to 155,707 km2 and 1030 km towards north to south and up to 500 km towards east to west and coastline of Odisha is 480 km. The state Odisha has 30 districts and its divided further in to 314 blocks.

Data Collection

To collect data about various objectives on The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL 4.0) and representative sample are collected using appropriate primary data collection technique based on the questionnaire of PedsQL 4.0. The data collection is done from the period April 2020 to May 2021. We have collected total 202 numbers of sample for our data analysis from all over the Odisha. Due to COVID-19 situation we have adopted the data collection method online mode. We created a google form provided by Google and by sharing it in latest social media platform we collected the 202 number of data and one semi-structure questionnaire was also adopted to check the quality of life before COVID-19 and during COVID-19.

Data Analysis

For this research we use the Statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics 22 as analysis tools. Here we found while analyze the before lockdown and after lockdown data we found all the data are normally assumptions and positively skewed and after transformation median and IQR (Inter Quartile Range) are represented by screen time variables. ICC or Intra Class Correlation Coefficient was assessed for relative reliability using two-way mixed effects. If the value is greater than 0.75 then it has excellent reliability and less than 0.40 has poor reliability and the value between 0.40-0.59 has fair reliability and the value between 0.60-0.74 has good reliability.

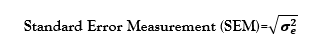

Here we have calculated Standard Error Measurement or SEM for Absolute reliability using the formula given below:

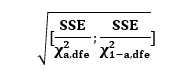

Where variance of error is denoted by is a repeated measures ANOVA or known as analysis of variance of two-sided 95% confidence interval was estimated by given formula below:

Where sum of square of error is denoted by SSE which is calculate from the ANOVA and the Chi-Square value is denoted by for probability level α and dfe is the degree of freedom. The consistency scores of individuals refer to the absolute reliability. Therefore, it tells us how similar the scores for repeated measure are when measurement error is present. For interquartile correlation coefficient (ICC) between 0.4-0.6 implies to acceptable reliability otherwise for an interquartile correlation coefficient (ICC) between 0.6-0.8 implies to good to excellent reliability.

Results

A total of 202 adults having age from 08-18 years from Odisha were enrolled in this research. From there 44.5% were male and 55.5% of them were female and from the primary data collection we found that 27.2% are Child having age 8-12 and 72.3% are Adolescent having age 13-18. In our study from 202 participants 92/80/12/18 are from caste General/OBC/SC/ST respectively. in our data we found that maximum family having two children that is 119 from 202. We get total 73 number of primary school students, 64 are from secondary school, 52 are from higher secondary college and 13 are graduation students. Most of the candidates are from government colleges/schools that is 112. Most of the middle-class family (183) candidates are participate in our study. Our study tells that most father are having education level is graduation (63) and most of the mother are having education level secondary (81). Most of the father are Businessman (76) and mothers are House wife (159). All this details information is given in table-1.

Table 1: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core total scale scores by gender, age, domicile, type of family and socio‑economic class for parent proxy report.

| Demographics | Child self‑report | Percentage missing values | Parent proxy report | Percentage missing values | ||

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | |||

| All | 202 | 56.73±13.11 | 00 | 202 | 55.83±12.70 | 00 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (1) | 90 | 59.29±13.08 | 00 | 90 | 56.9912.78 | 00 |

| Female (2) | 112 | 54.66±12.82 | 00 | 112 | 54.9112.62 | 00 |

| Age | ||||||

| Child (8‑12) | 55 | 51.00±4.07 | 00 | 55 | 48.77±13.80 | 00 |

| Adolescent (13‑18) | 147 | 58.87±12.10 | 00 | 147 | 58.48±11.22 | 00 |

| Caste | ||||||

| General (1) | 92 | 58.43±11.76 | 00 | 92 | 58.54±11.14 | 00 |

| OBC (2) | 80 | 55.48±13.96 | 00 | 80 | 53.88±13.60 | 00 |

| SC (3) | 12 | 49.63±18.45 | 00 | 12 | 47.91±15.73 | 00 |

| ST (4) | 18 | 58.27±10.27 | 00 | 18 | 55.97±11.06 | 00 |

| Total no. of children in a family | ||||||

| 1 | 27 | 54.22±14.36 | 00 | 27 | 53.38±13.35 | 00 |

| 2 | 119 | 56.91±12.56 | 00 | 119 | 56.59±12.14 | 00 |

| 3 | 47 | 57.19±14.15 | 00 | 47 | 55.31±13.58 | 00 |

| 4 or More | 9 | 59.42±11.74 | 00 | 9 | 55.91±14.52 | 00 |

| Order of child for filling this form | ||||||

| 1 | 109 | 54.92±13.52 | 00 | 109 | 54.93±12.60 | 00 |

| 2 | 63 | 59.42±12.30 | 00 | 63 | 57.24±12.59 | 00 |

| 3 | 25 | 56.65±13.43 | 00 | 25 | 55.91±14.47 | 00 |

| 4 or More | 5 | 62.60±5.19 | 00 | 5 | 57.39±7.18 | 00 |

| School/ College class | ||||||

| Primary | 73 | 53.84±14.15 | 00 | 73 | 51.93±13.87 | 00 |

| Secondary | 64 | 56.67±12.41 | 00 | 64 | 56.47±11.49 | 00 |

| Higher Secondary | 52 | 60.49±12.37 | 00 | 52 | 59.48±11.80 | 00 |

| Graduation | 13 | 58.19±10.21 | 00 | 13 | 60.03±9.56 | 00 |

| Type of school / College | ||||||

| Government | 112 | 56.75±14.57 | 00 | 112 | 56.00±13.57 | 00 |

| Private | 90 | 56.70±11.11 | 00 | 90 | 55.62±11.61 | 00 |

| Residence Area | ||||||

| Rural | 91 | 55.66±14.98 | 00 | 91 | 54.30±14.15 | 00 |

| Semi-Urban | 51 | 59.31±9.22 | 00 | 51 | 57.52±8.51 | 00 |

| Urban | 60 | 56.15±12.78 | 00 | 60 | 56.73±13.27 | 00 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| High class | 2 | 41.84±5.38 | 00 | 2 | 43.47±4.61 | 00 |

| Middle class | 183 | 56.91±13.02 | 00 | 183 | 56.08±12.50 | 00 |

| Low class | 17 | 56.45±14.17 | 00 | 17 | 54.66±15.07 | 00 |

| Father’s Education | ||||||

| Primary | 24 | 54.66±14.47 | 00 | 24 | 54.71±12.39 | 00 |

| Secondary | 46 | 54.08±15.37 | 00 | 46 | 52.12±15.34 | 00 |

| Higher Secondary | 43 | 59.93±10.88 | 00 | 43 | 59.12±8.28 | 00 |

| Graduation | 63 | 56.86±12.30 | 00 | 63 | 55.67±12.34 | 00 |

| PG or above | 26 | 57.69±12.43 | 00 | 26 | 58.40±13.71 | 00 |

| Father’s Occupation | ||||||

| Government Employee | 41 | 56.44±11.36 | 00 | 41 | 57.71±11.85 | 00 |

| Private Employee | 55 | 58.62±12.84 | 00 | 55 | 58.76±10.92 | 00 |

| Business | 76 | 58.49±11.96 | 00 | 76 | 56.16±11.77 | 00 |

| Others | 30 | 53.47±15.48 | 00 | 30 | 52.39±14.85 | 00 |

| Mother’s Education | ||||||

| Primary | 31 | 55.43±13.59 | 00 | 31 | 54.83±13.13 | 00 |

| Secondary | 81 | 55.34±14.54 | 00 | 81 | 53.51±13.95 | 00 |

| Higher Secondary | 32 | 57.60±13.11 | 00 | 32 | 59.06±9.66 | 00 |

| Graduation | 44 | 58.44±11.02 | 00 | 44 | 56.81±12.26 | 00 |

| PG or above | 14 | 60.24±8.79 | 00 | 14 | 61.02±9.29 | 00 |

| Mother’s Occupation | ||||||

| House Wife | 159 | 57.27±13.36 | 00 | 159 | 56.22±13.00 | 00 |

| Government Employee | 16 | 58.49±12.15 | 00 | 16 | 58.28±13.00 | 00 |

| Private Employee | 7 | 51.39±10.53 | 00 | 7 | 54.19±7.79 | 00 |

| Business | 11 | 51.28±12.46 | 00 | 11 | 51.08±11.09 | 00 |

| Others | 9 | 54.83±12.58 | 00 | 9 | 51.69±11.67 | 00 |

| * Upper class were clubbed into upper middle class as the number of cases in upper (n=11) were small. Socio‑economic class was defined by modified Kuppuswamy’s scale 2012. NA, not available; SD, standard deviation | ||||||

Table 2shows the scale descriptive from the research sample. For the overall sample or age-based subgroups, social functioning had the highest scores while emotional functioning had the lowest scores. Both the child self-report and the parent proxy report followed the same pattern.

Table 2: Scale descriptive for Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scale by age group (total, child and adolescent).

| Scale | Child self‑report | Parent proxy report | ||||

| Mean ± SD | Alpha | SEM* | Mean ± SD | Alpha | SEM* | |

| ALL | ||||||

| Total score | 56.73±13.11 | 0.866 | 0.92 | 55.83±12.70 | 0.856 | 0.89 |

| Physical health | 59.52±17.71 | 0.901 | 1.24 | 58.32±17.87 | 0.883 | 1.25 |

| Psychosocial health | 55.23±12.95 | 0.962 | 0.91 | 54.51±12.62 | 0.953 | 0.88 |

| Emotional functioning | 51.31±15.77 | 0.675 | 1.11 | 49.52±15.36 | 0.667 | 1.08 |

| Social functioning | 64.57±21.15 | 0.831 | 1.48 | 64.62±21.14 | 0.822 | 1.48 |

| School functioning | 49.82±17.32 | 0.761 | 1.21 | 49.38±16.32 | 0.744 | 1.14 |

| Child (8‑12) | ||||||

| Total score | 51.00±14.07 | 0.904 | 1.89 | 48.77±13.80 | 0.898 | 1.86 |

| Physical health | 50.85±17.76 | 0.896 | 2.39 | 47.67±16.41 | 0.878 | 2.21 |

| Psychosocial health | 51.09±14.66 | 0.965 | 1.97 | 49.36±15.18 | 0.965 | 2.04 |

| Emotional functioning | 50.54±17.04 | 0.758 | 2.29 | 47.72±17.94 | 0.844 | 2.42 |

| Social functioning | 56.27±20.71 | 0.830 | 2.79 | 53.09±21.15 | 0.806 | 2.85 |

| School functioning | 46.45±17.62 | 0.896 | 2.37 | 47.27±18.32 | 0.829 | 2.47 |

| Adolescent (13‑18) | ||||||

| Total score | 58.87±12.10 | 0.839 | 0.99 | 58.48±11.22 | 0.817 | 0.92 |

| Physical health | 62.77±16.62 | 0.896 | 1.37 | 62.30±16.77 | 0.869 | 1.38 |

| Psychosocial health | 56.79±11.94 | 0.959 | 0.98 | 56.43±10.97 | 0.942 | 0.9 |

| Emotional functioning | 51.59±15.32 | 0.642 | 1.26 | 50.20±14.29 | 0.541 | 1.17 |

| Social functioning | 67.68±20.53 | 0.817 | 1.69 | 68.94±19.51 | 0.804 | 1.61 |

| School functioning | 51.08±17.09 | 0.681 | 1.41 | 50.17±15.49 | 0.696 | 1.27 |

| *SEM was calculated by multiplying the SD by the square root of 1‑alpha (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient), # Parent proxy report of school functioning (2‑4 years) data are from 97 respondents. NA, not available; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of mean. | ||||||

The total HRQOL score had an internal consistency reliability of 0.87 for the child form and 0.86 for the parent version (Table II). With the exception of emotional functioning (child & parent forms) and school functioning in the child form, the sample demonstrated strong internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha >0.7) across domains for both child and parent reports. When the results were stratified by age, emotional and school functioning showed less internal consistency between the areas. Across all age groups, this tendency was observed for both child and parent forms. For both child (56.73 vs. 83.91, P less than 0.001) and parent proxy reports (55.83 vs. 82.29, P less than 0.001), the mean values for total HRQOL score in the current study (age group 8-18 yr) were substantially different from the reference paper by Varni et al. As the reference data were produced from children aged 8-18 yr., this comparison was conducted after building a comparable sample (children aged 8-18 yr. only) from the complete sample. In addition, mean scores for physical health, psychosocial health, emotional functioning, social functioning, and school functioning differed between the two studies on age-appropriate comparisons in both child and parent reports. The specifics are given in Table. III.

Table 3: Comparison of health‑related quality of life scores b/w the current study and the study by Varni et.al 14.

| Score on scale | Current study | Varni et.al 14 | Mean difference | P-value | Effect size | |

| Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Child report (n=202) | ||||||

| Total score | 56.73±13.11 | 5079 | 83.91±12.47 | -27.18 | 0.000 | 0.59 |

| Physical health | 59.52±17.71 | 5070 | 87.77±13.12 | -28.25 | 0.000 | 0.69 |

| Psychosocial health | 55.23±12.95 | 5070 | 81.83±13.97 | -26.6 | 0.000 | 0.52 |

| Emotional functioning | 51.31±15.77 | 5068 | 79.21±18.02 | -27.9 | 0.674 | 0.64 |

| Social functioning | 64.57±21.15 | 5056 | 84.97±16.71 | -20.4 | 0.001 | 0.55 |

| School functioning | 49.82±17.32 | 5026 | 81.31±16.09 | -31.49 | 0.091 | 0.26 |

| Parent report (n=202) | ||||||

| Total score | 55.83±12.70 | 8713 | 82.29±15.55 | -26.46 | 0.000 | 0.77 |

| Physical health | 58.32±17.87 | 8696 | 84.08±19.70 | -25.76 | 0.000 | 0.88 |

| Psychosocial health | 54.51±12.62 | 8714 | 81.24±15.34 | -26.73 | 0.000 | 0.53 |

| Emotional functioning | 49.52±15.36 | 8692 | 81.20±16.40 | -31.68 | 0.309 | 0.15 |

| Social functioning | 64.62±21.14 | 8690 | 83.05±19.66 | -18.43 | 0.000 | 0.77 |

| School functioning | 49.38±16.32 | 7287 | 78.27±19.64 | -28.89 | 0.262 | 0.17 |

| *The comparison was restricted to the age group of 2‑16 years as Varni et.al 14 had no adolescents in the age group 17‑18 years. The P values are for the independent t tests for comparison of means. Effect size was calculated using pooled SD | ||||||

For both child (56.73 vs. 87.39, P<0>

Table 4: Comparison of health‑related quality of life scores b/w the current study and the study by Manu Raj, 17.

| Score on scale | Current study | Manu Raj et.al 17 | Mean difference | P-value | Effect size | |

| Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Child report (n=202) | ||||||

| Total score | 56.73±13.11 | 538 | 87.39±11.11 | -30.66 | 0.000 | 0.59 |

| Physical health | 59.52±17.71 | 538 | 91.72±11.73 | -32.2 | 0.000 | 0.69 |

| Psychosocial health | 55.23±12.95 | 538 | 85.08±12.42 | -29.85 | 0.000 | 0.52 |

| Emotional functioning | 51.31±15.77 | 538 | 76.89±17.86 | -25.58 | 0.674 | 0.64 |

| Social functioning | 64.57±21.15 | 538 | 94.18±12.46 | -29.61 | 0.001 | 0.55 |

| School functioning | 49.82±17.32 | 538 | 84.18±15.81 | -34.36 | 0.091 | 0.26 |

| Parent report (n=202) | ||||||

| Total score | 55.83±12.70 | 672 | 90.03±9.47 | -34.2 | 0.000 | 0.77 |

| Physical health | 58.32±17.87 | 672 | 93.44±12.33 | -35.12 | 0.000 | 0.88 |

| Psychosocial health | 54.51±12.62 | 672 | 87.82±9.80 | -33.31 | 0.000 | 0.53 |

| Emotional functioning | 49.52±15.36 | 672 | 79.12±14.23 | -29.6 | 0.309 | 0.15 |

| Social functioning | 64.62±21.14 | 672 | 96.76±10.09 | -32.14 | 0.000 | 0.77 |

| School functioning | 49.38±16.32 | 672 | 87.73±15.42 | -38.35 | 0.262 | 0.17 |

| *The comparison was restricted to the age group of 2‑16 years as Manu Raj et.al 17 had no adolescents in the age group 17‑18 years. The P values are for the independent t tests for comparison of means. Effect size was calculated using pooled SD | ||||||

ICC looked into the agreements between the parent/caretaker and the kid in terms of reporting HRQOL totals and sub-scores (two-way mixed effects). Except for school functioning, there was good agreement (ICC 0.61-0.77) between the two groups on all HRQOL categories in the five-to-seven-year age range. Except for emotional and social functioning, all HRQOL categories showed good agreement in the 8–12-year-old age range. Except for physical health and educational performance, the same pattern was observed in the 13–18-year-old age group. In all of the HRQOL domains, there was moderate to fair agreement between child and parent reports across all age groups. Table V contains all of the pertinent information.

Table 5: Intra‑class correlations (ICC)# between child self‑report and parent proxy report for Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scales.

| Scale score | Age group (yr) | ||

| Overall | Child (8‑12) | Adolescent (13‑18) | |

| Total score | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.68 |

| Physical health | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.67 |

| Psychosocial health | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.67 |

| Emotional functioning | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| Social functioning | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.72 |

| School functioning | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.59 |

| # ICC was calculated by two‑way mixed effect model (absolute agreement, single measures). All values are significant at P<0> | |||

The total score as well as specific domain scores were compared among subgroups based on age, sex, residence location, and socioeconomic status (SES). Both older children (8-12 year) (51.00 vs. 87.3, =0.042) and adolescents (13-18 yr) (58.87 vs. 86.0, P=0.001) reported significantly higher HRQOL total scores than younger children (5-7 yr). In the parent proxy report, there was no corresponding pattern. Physical health (59.52 vs. 90.1, P=0.000), psychosocial health (55.23 vs. 83.8, P=0.000), emotional functioning (51.31 vs. 75.2, P=0.000), and school functioning (49.82 vs. 82.4, P=0.091) were all areas where younger children outperformed teenagers.

Table 6: To know the quality of life the Children and Teenagers before and after COVID-19 Pandemic by the Semi-Structure Questionnaire.

| Sl. No. | Semi-Structure Questionnaire | N | Median | IQR | ICC | SEM | 95% confidence interval | P-Value |

| 1 | How much of time (excluding study hours) your child was spending time in screen (TV/smart phone/laptop etc.) before COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 2 | 1.25 | 0.484 | 0.61 | 0.319-0.609 | 0.000 |

| 2 | How much of time (excluding study hours) your child was spending time in screen (TV/smart phone/laptop etc.) during COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 4 | 1 | 0.484 | 0.65 | 0.319-0.609 | 0.000 |

| 3 | How do you see the educational performance of your child, now as compare to before COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 2 | 3 | 0.103 | 0.88 | -0.074-0.383 | 0.07 |

| 4 | How do you rate your child’s interest in playing game / involvement in any extracurricular activities before COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 3 | 1 | 0.103 | 0.56 | -0.074-0.383 | 0.07 |

| 5 | How do you rate your child’s interest in playing game / involvement in any extracurricular activities during COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 3 | 3 | 0.257 | 0.90 | 0.019-0.437 | 0.01 |

| 6 | How do you see your child is Enjoying his/her life now as compare to before COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 3 | 2.25 | 0.257 | 0.86 | 0.019-0.437 | 0.01 |

| 7 | How do you see changes in Quality of Life of your child now as compare to before COVID-19 Pandemic? | 202 | 1 | 2 | 0.432 | 0.84 | 0.313-0.538 | 0.00 |

| 8 | Rate your child's experience during last one month especially with regard to COVID-19 Pandemic. | 202 | 1 | 2 | 0.604 | 0.89 | 0.477-0.700 | 0.00 |

| *For (1-2) 1= 1hrs, 2= 2hrs, 3= 3hrs, 4= 4hrs and more | ||||||||

| *For (3-8) 1= Poor, 2= Neither poor nor good, 3=Good, 4= Excellent | ||||||||

Table 6 compares the quality of life before and after covid-19. Question 1,2,7,8 has an ICC of 0.48-0.60, while the SEM is 0.90. For questions 1,2,7,8, we receive the significant value. The analysis shows that HRQL before covid-19 is lower than it is during covid-19.

Discussion

In both direct and proxy report formats, the current study provides data on HRQOL of normal children and adolescents. The study also allows for an age-appropriate comparison of HRQOL between children and adolescents in the United States and Kerala, India, as well as their Odisha counterparts. It also includes a number of sub-groups stratified total HRQOL ratings, allowing for thorough inter-group comparisons.

When HRQOL scores (total, summary, and sub-domains) were compared between the reference study and the current study, there was a significant difference between the three populations. When compared to their US counterparts and Kerala, India, all HRQOL scores for children/adolescents from the current study were significantly lower (Varni JW et.al, 2001). The large range of mean differences (verni et al. -31.68 to 13.71 and manuraj et al. -2.08 to -38.35) and effect sizes (verni et al. 0.15 to 0.72 and manuraj et al. 0.15 to -0.13) suggests that HRQOL reference values for children/adolescents should be derived from respective populations. that share ethnic, cultural and socio-economic scenarios. In addition, the MCID as denoted by the corresponding SEM values is lower for study children compared to US children and Kerala, India.

Several methodological discrepancies exist between the three investigations, which could explain the reported differences. In the reference study, the sample was made up of uninsured people, whereas in the current study, the sample was made up of everyone. Between the reference and the current study, there was a substantial variation in the enrolling response rate (verni et.al. 51 vs 100 % and manuraj et.al 99 vs 100 %) The three research also used different types of data collecting (mailed questionnaire and home visits vs Online Google form). Other possible explanations for the observed discrepancy include study time (2001 and 2015 vs. 2021), administration language (five vs. one), and ethnicity (multi-ethnic vs. single ethnic). PedsQL 4.0 offers strong feasibility and fair reliability for both child and parent proxy reports among Indian children across all HRQOL scores, according to the study findings. In the current study, emotional functioning had the lowest dependability among the sub-domains. The current study's dependability metrics were similar to those published by Varni et al. and Manuraj et al.

The current study's child vs parent report agreement levels, as measured by ICC, were equivalent to those reported by Varni et al. The clinical importance of the real discrepancy between child and parent reporting of HRQOL is uncertain, according to a review of parent-child agreement across paediatric HRQOL tests (Upton P et.al.,2008). According to the study, there are two major causes for this: either a lack of parental understanding about their children's experiences and ideas, or a discrepancy in self- and other-perspective. It also mentions that parents' levels of awareness, sensitivity, and tolerance for their children's health difficulties differ (Upton P et.al.,2008). The same reasons may have played a role in the differential reporting of HRQOL by children and parents in the current study.

In our research, younger children had higher HRQOL scores than older children. This age pattern was comparable to those found in a recent evaluation of 37 studies on children and adolescents' self-reported QOL (Jardine J et.al., 2014). In both the current study and the previous review, no such trend could be found among parent proxy reports (Jardine J et.al., 2014).

HRQOL data from developing nations such as China (Zheng S, et al 2011) and Brazil were compared to the findings of this study (Ciconelli RM, et al,2008). The data from China revealed a pattern that was comparable to what we found in our research. Both studies found that social functioning had the highest maximum score and emotional functioning had the lowest minimum score. Both the child and parent reports showed the same pattern. The data from Brazil, on the other hand, indicated a trend that was comparable to that of Varni et al 2014. In contrast to the current study and the Chinese study, both Brazilian and US data indicated maximum scores for physical health (for both child and parent forms). The lowest scores for both the US and Brazilian data were for emotional functioning on both the child and parent forms, which was similar to the current study as well as studies from China (Zheng S, et al 2011) and Kerala, India (Manu Raj et.al. 2015).

Sex-based variations in HRQOL total and various sub-domain-based scores were found in the current study to be consistent with previously published studies from other countries (Viira R et al., 2011). Female adolescents exhibited considerably poorer total HRQOL values, as well as physical health, emotional functioning, and psychosocial health categories, than their male counterparts, according to an Estonian study (Viira R et.al.,2011). In one Norwegian study (Reinfjell T et al.,2006), a sex difference was seen only in the emotional functioning sub-scale. In the current study, this conclusion was limited to direct (child) reports and not proxy (parent) reports for HRQOL. In the field of HRQOL research, the fact that rural children from low-resource situations, as well as their parents, reported better HRQOL than their urban counterparts, is an interesting finding. This rural-urban HRQOL disparity, which may be seen in both types of reporting, is likely related to disparities in rural and urban populations' perceptions and expectations regarding QOL and life amenities.

Our study had a high enrollment response rate, which reduced selection bias. For increased generalizability, the study included both rural and urban populations, as well as diverse socioeconomic levels. The study sample's age structure was comparable to that of Census 2011, enhancing the findings' generalizability to the general population. In comparison to Varni et al and Manu Raj et al, we can see that our study's mean and standard deviation are much lower. This demonstrates that the health-related quality of life during the Covid-19 epidemic is significantly lower than before the pandemic. We may also argue that the pandemic crisis has changed everyone's way of life, and many individuals are experiencing difficulties with their health-related quality of life.

Conclusion

In this study, healthy children and adolescents from Odisha, India was given HRQOL reference values. This HRQOL nomogram, along with several others from across India, will aid researchers in developing a pooled country-specific HRQOL reference for Indian youngsters. In this study, we can also detect a significant difference in HRQL before and after covid-19. We can see that it has a significant impact on the children and adults of Odisha, India. This type of HRQOL reference could let researchers apply it to a variety of pediatric diseases/disorders and compare it to the HRQOL of their normal counterparts in a contextually appropriate manner.

References

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Lane MM. (2005). Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: An appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 3(34):1-9.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fayers PM, Machin D. (2000). Quality of life: Assessment, analysis, and interpretation. New York, Wiley.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Spilker B. (1996). Quality of life and Pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. (1999). Pediatric health-related quality of life measurement technology: A guide for health care decision makers. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 6:33-40.

Publisher | Google Scholor - World Health Organization. (1948). Constitution of the World Health Organization: Basic Document. Geneva, Switzerland.

Publisher | Google Scholor - FDA. (2006). Guidance for Industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Rockville.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M. (2005). The PedsQL™ as a pediatric patient-reported outcome: Reliability and validity of the PedsQL™ Measurement Model in 25,000 children. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 5:705-719.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Schwimmer JB, Middleton MS, Deutsch R, Lavine JE. (2005). A phase 2 trial of metformin as a treatment for non-diabetic pediatric nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 21:871-879.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Connelly M, Rapoff MA. (2006). Assessing health-related quality of life in children with recurrent headache: Reliability and validity of the PedsQL™ 4.0 in a pediatric sample. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31:698-702.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Willke RJ, Burke LB, Erickson P. (2004). Measuring treatment impact: A review of patient-reported outcomes and other efficacy endpoints in approved product labels. Controlled Clinical Trials, 25:535-552.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sherman SA, Eisen S, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. (2006). The PedsQL™ Present Functioning Visual Analogue Scales: Preliminary reliability and validity. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4:75:1-10.

Publisher | Google Scholor - McHorney CA. (1999). Health status assessment methods for adults: Past accomplishments and future challenges. Annu Rev Public Health, 20:309-335.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Idler EL, Benyamini Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav, 38:21-37.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Patrick DL, Deyo RA. (1929). Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care, 27(3):S217-S232.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. (1999). The PedsQL: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care, 37:126-139.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. (2007). Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: A comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 5:43.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Sherman SA, Hanna K, Berrin SJ. et al. (2005). Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: Hearing the voices of the children. Dev Med Child Neurol, 47 : 592-597.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Thavorncharoensap M, Torcharus K, Nuchprayoon I, Riewpaiboon A, Indaratna K, et al. (2010). Factors affecting health-related quality of life in Thai children with thalassemia. BMC Blood Disord, 10:1.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Massad SG, Nieto FJ, Palta M, Smith M, Clark R et al. (2011). Health-related quality of life of Palestinian preschoolers in the Gaza Strip: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 11:253.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Awasthi S, Agnihotri K, Chandra H, Singh U, Thakur S. (2011). Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in school-going adolescents: Validation of PedsQL instrument and comparison with WHOQOL-BREF. Natl Med J India, 25:74-79.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Banerjee T, Pensi T, Banerjee D. (2010). HRQoL in HIV-infected children using PedsQL 4.0 and comparison with uninfected children. Qual Life Res., 19:803-812.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. (2001). PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care, 39:800-812.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Seid M, Knight TS, Uzark K, Szer IS. (2002). The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales: Sensitivity, responsiveness, and impact on clinical decision-making. J Behav Med. 25:175-193.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. (2003). The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr, 3:329-341.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Census of India. (2011).

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. (2012). Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year. Indian J Public Health, 56:103-104.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. (2007). How young can children reliably and validly self-report their health-related quality of life? an analysis of 8,591 children across age subgroups with the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes; 5:1.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C. (2008). Parent-child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: A review of the literature. Qual Life Res 17:895-913.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jardine J, Glinianaia SV, McConachie H, Embleton ND, Rankin J. (2014). Self-reported quality of life of young children with conditions from early infancy: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 134:e1129-1148.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ji Y, Chen S, Li K, Xiao N, Yang X, Zheng S, et al. (2011). Measuring health-related quality of life in children with cancer living in mainland China: feasibility, reliability and validity of the Chinese mandarin version of PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales and 3.0 Cancer Module. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9:103.

Publisher | Google Scholor