Research Article

Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: The Hidden Cause of Gastrointestinal Problems in Children Undergoing Surgeries

- Shabnam Eskandarzadeh 1

- Sepideh Darougar 2

- Maryam Kazemi Aghdam 3

- Mohsen Rouzrokh 4

- Mohammad-Reza Sohrabi 5

- Niusha Sharifinejad 6

- Mahboubeh Mansouri 1*

1 Allergy and clinical immunology department, Mofid Children Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2 Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

3 Department of Pathology, Pediatric Pathology Research Center, Mofid Pediatric Medical Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4 Pediatric Surgery Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5 Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Community Medicine Department, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

6 Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

*Corresponding Author: Mahboubeh Mansouri, Allergy and clinical immunology department, Mofid Children Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Citation: Eskandarzadeh S, Darougar S, Maryam K Aghdam, Rouzrokh M, Mansouri M, et al. (2024). Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: The Hidden Cause of Gastrointestinal Problems in Children Undergoing Surgeries, International Clinical Case Reports and Reviews, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 2(3):1-8. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0855.brs.24.017

Copyright: © 2024 Mahboubeh Mansouri, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: July 15, 2024 | Accepted: August 02, 2024 | Published: September 05, 2024

Abstract

Background: Considering that non-eosinophilic esophagitis EGIDs could mimic serious surgical conditions, including hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, intussusception, and bowel perforation, we aimed to investigate what proportion of the patients who had undergone GI surgeries were suffering from that.

Methods: Children who had undergone GI surgeries between March 2017 and March 2018 at Mofid Children's Hospital, Tehran, were randomly selected and their pathologic specimens were re-evaluated.

Results: Seventy-two pediatric patients with a median age of 2.5 years, suffering from constipation and abdominal pain were studied. The majority of patients were primarily diagnosed with Hirschsprung’s syndrome (38.9%), followed by imperforated anus (34.7%) and ileal atresia (16.7%). Among the studied patients ten (13.9%) were confirmed to have tissue eosinophilia, compatible with conventional method of non-EoE EGID diagnosis. More evidence supporting the presence of tissue eosinophils were infiltration of 1-26 eosinophils in the muscular and subserosal layers of more than 97% of samples, degranulated eosinophils and multi-nucleated cells in 6 (8.3%) tissue samples, and different levels of tissue fibrosis in 37 patients (51.4%).

Conclusion: Non-EoE EGIDs should be considered in the context of severe relapsing GI complications requiring urgent or emergent surgical interventions, particularly in those without a convenient response after surgeries.

Keywords: eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases; non-EoE EGIDs; food allergy; skin prick test; gastrointestinal surgery

Introduction

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) are a rare group of heterogeneous disorders characterized by the presence of eosinophilic infiltration in specific sections of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, causing clinical signs and symptoms related to the involved segment(s), and the absence of any other underlying disorders [1-3]. Eosinophils are innate immune cells traditionally associated with allergic diseases and parasitic infections [4]. Over-activation of these immune cells may induce T helper 2 (Th2)-mediated cytokine release and cause subsequent tissue damage observed in patients with EGIDs [5,6]. Since food allergens are mostly known as potential triggers of eosinophilic inflammation in GI tract of the affected children, the elimination of these kinds of food may remarkably improve their clinical conditions [7,8]. Allergic diseases comorbidities, including food allergy, asthma and allergic rhinitis have been widely reported in patients with EGIDs [9]. In addition, these patients have a constellation of unmet needs, which could significantly impact their lives [10]. More than half of these patients experience delays in diagnosis often due to transition through multiple health-providers [10].

Considering the different levels of GI tract involvement, EGIDs are categorized into four groups comprising eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis. It is noteworthy that the location of the GI involvement is responsible for specific symptoms appearing in each patient. For example, the involvement of the muscle layer mainly causes bowel obstruction, and subserosal layer involvement is also predominantly associated with eosinophilic ascites [11]. Some studies have reported that non-EoE EGIDs could mimic serious surgical conditions, including hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS), intussusception, and bowel perforation, leading to surgical complications, especially in pediatric patients, whereas the removal of the probable allergen or administrating immunosuppressive drugs could simply resolve the symptoms [12-14]. Considering the fact that 11-85%) of the total global burden of all disorders is attributable to surgically-treated diseases [15], and knowing that patients with non-EoE EGIDs tend to undergo more surgical procedures due to the higher chance of recurring symptoms as well as diagnostic difficulties [16], achieving a better understanding of this disease is of paramount importance. At present, no guidelines exist for diagnosis or treatment of non-EoE EGIDs [2].

Given the above, we aimed to investigate what proportion of the pediatric patients who had undergone GI surgeries were in fact suffering from non-EoE EGIDs. This study outlines how the timely diagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs may prevent unnecessary surgeries to improve the patients’ clinical conditions through eliminating food allergens and/or immunosuppressive medications.

Material and Methods

Patients

The patients were randomly selected from the children who had undergone GI surgeries between March 2017 and March 2018 at the Surgical Department of Mofid Children's Hospital (Tehran, Iran) affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Those patients who were older than 18 at the time of surgery, were operated secondary to trauma, had inadequate tissue samples, or were affected by other known secondary causes of eosinophilia were excluded from the study. Finally, a total of 72 patients fulfilled the criteria and underwent subsequent analyses.

Ethics

Prior to data collection, written informed consents were obtained from the patients and/or their caregivers/parents. All the experiments were approved by the local ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the reference No. of IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1398.501 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Samples collection and demographic data

After evaluation of the gastrointestinal pathologic specimens of the patients, an appropriate form was developed to collect the demographic data from the patients’ medical records or by direct interviews and medical examinations. The form included age, sex, family history of allergy, present and prior allergic diseases comorbidities [asthma, allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis], and clinical pre- and post-surgery GI, non-GI, and allergic manifestations. This form was designed according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2018) guideline for food allergy symptoms [17]. CBC values were obtained from the patients’ medical records at the time of admission and were compared to normal age-adjusted ranges.

Skin prick test for food allergens including cow’s milk, meat, egg, sesame, nuts (walnut, peanut, hazelnut, pistachio), barley, and wheat was subsequently performed on all of the patients.

Histological assessment

GI biopsy specimens, previously collected from the patients during surgeries, were reassessed by a pathologist with special attention to eosinophil infiltration or its footprint, such as fibrosis, degranulated eosinophils and multinucleated cells, in different layers of GI specimens. The number of eosinophils per high-power field (HPF), as the main and conventional criterion for diagnosis of EGID, was measured and compared with normal pediatric values in each part of the GI tract described by DeBrosse et al. [18].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (v. 26.0, Chicago, IL). Median and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for quantitative variables with abnormal distribution. Qualitative data were interpreted using number and percentage.

Results

Demographic data

The data evaluation of 72 pediatric patients (41 males, 31 females) who underwent GI surgeries at a median (IQR) age of 2.5 (1.2-11.0) years showed that 28 patients were operated due to hirschsprung’s syndrome (38.9%), followed by 25 imperforated anus (34.7%) and 12 ileal atresia cases (16.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: An illustration of the causes of gastrointestinal surgeries in pediatric patients

The results of the skin prick tests were positive in 31 cases (43%), yet there was no significant difference between the patients undergoing different surgical operations. Only 6.9% of the patients (5 out of 72) had positive family history of allergy. Milk (19 patients) and egg (14 patients) were the most frequent food allergens.

Clinical presentations

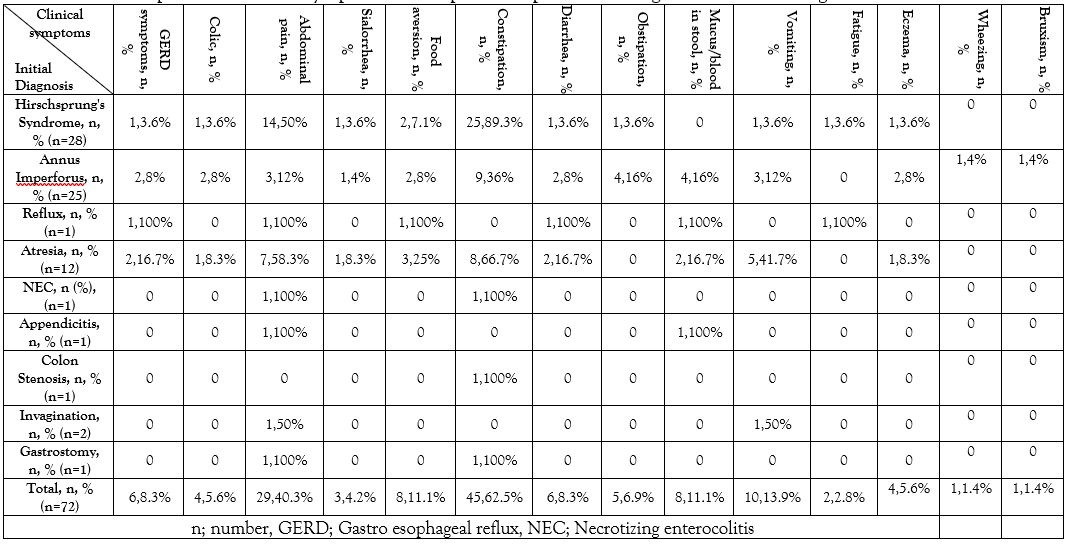

Constipation, abdominal pain, and vomiting were the most common reported pre-surgical symptoms with 62.5% (45 patients), 40.3% (29 patients), and 13.9% (10 patients), respectively. After comparing these clinical symptoms in each diagnostic group, it was found out that constipation and abdominal pain were more common in Hirschsprung’s syndrome and mucus/or blood in stool was frequently found in surgically-repaired imperforated anus after operation (Table 1).

Table 1: Pre-operation clinical symptoms of 72 pediatric patients with gastrointestinal surgeries.

The recurrence of GI symptoms after surgery, including constipation (31 cases, 43.1%), abdominal distension (30 cases, 41.7%), obstipation (28 cases, 38.9%), and vomiting (9 cases, 12.5%), were observed in all the patients, even after the initial surgical interventions (Table 2), suggesting another underlying disorder other than the initial diagnoses.

Table 2: Post-operation clinical symptoms of 72 pediatric patients with gastrointestinal surgeries.

| Clinical symptoms Initial Diagnosis | Constipation, n, % | Abdominal distension, n, % | Obstipation, n, % | Vomiting, n, % |

| Hirschsprung's Syndrome, n, % (n=28) | 12, 42.9% | 13, 46.4% | 9, 32.1% | 4, 14.3% |

| Annus Imperforus, n, % (n=25) | 10, 40% | 10, 40% | 13, 52% | 3, 12% |

| Reflux, n, % (n=1) | 1, 100% | 1, 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Atresia, n, % (n=12) | 4, 33.3% | 5, 41.7% | 3, 25% | 2, 16.7% |

| NEC, n, % (n=1) | 1, 100% | 0 | 1, 100% | 0 |

| Appendicitis, n, % (n=1) | 1, 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colon Stenosis, n, % (n=1) | 1, 100% | 1, 100% | 1, 100% | 0 |

| Invagination, n, % (n=2) | 1, 50% | 0 | 1, 50% | 0 |

| Gastrostomy, n, % (n=1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total, n, % (n=72) | 31, 43.1% | 30, 41.7% | 28, 38.9% | 9, 12.5% |

Peripheral blood cells findings and allergic lab data

Normal WBC, platelet and lymphocyte counts with low hemoglobin levels were found in 88.4%, 73.5%, and 48.8% of the patients, respectively. However, most patients (46 out of 72) were reported to have blood eosinophilia (63.9%).

Histologic Findings

Except for 2 patients (2.8%), a range of 1-35 eosinophils/HPF, not normally found in healthy children, was detected in the muscular or serosal layers of the patients’ specimens. Additionally, 1-26 eosinophils/HPF were reported in the sub serosal layers of specimens in 70 patients (97.2%). Six specimens (8.3%) revealed degranulated eosinophils and multi-nucleated cells. Ten patients revealed tissue eosinophilia compatible with EGID according to conventional diagnostic criteria (13.9%). Four of these patients underwent surgery for Hirschsprung disease (40%), three for imperforated anus (30%), and one for ileal atresia (10%), intussusception (10%), and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC, 10%) each. However, tissue eosinophilia was not taken into consideration initially in any of the aforementioned conditions prior to the surgeries. Almost half of the patients (37 of 72, 51.4%), including all of those with tissue eosinophilia, had different levels of tissue fibrosis in the collected specimens. Furthermore, due to hemorrhagic mucosa in two specimens, it was not pathologically possible to become certain about the existence of eosinophilic infiltration.

Constipation, vomiting and abdominal pain were the most common presentations. Peripheral blood eosinophilia was present in 70% and 63.2% of the patients with and without tissue eosinophilia (according to conventional diagnostic criteria), respectively. Skin prick test was positive in 8 out of ten patients whose tissue eosinophilia exceeded the cut-off limit. The results of egg and cow’s milk skin prick tests were positive in 6 and 4 of these patients, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, 70 patients who had undergone intestinal surgeries were recalled for further interviews as well as skin prick tests. An expert pathologist also reexamined the patients’ histopathology specimens for the second time. Additionally, their histopathologic specimens were evaluated again. The aim of this evaluation was to detect tissue eosinophilia, caused by non EoE EGID as the underlying disease, leading to surgical operations in the course of the disease. The allergic background of these patients was also evaluated.

Almost 14% of the patients' specimens matched the conventional diagnostic criteria for non-EoE EGID, which was mainly relied on the number of eosinophils in the tissue [18]. The post-operative diagnoses in the majority of these patients were congenital gastrointestinal developmental disorders, including Hirschsprung’s disease followed by imperforated anus and ileal atresia. Interestingly, all the patients experienced recurrent GI symptoms (mainly constipation and abdominal pain) before and even after the surgeries. Relying on the classical diagnosis method of non-EoE EGID (i.e., counting tissue eosinophils alone), it was diagnosed in 13.9% of the patients in the present study, which is 5000 times more than the general population (2.5/100,000) [19].

In light of the two facts presented above (recurrent GI symptoms and a higher prevalence rate of non EoE EGIDs), we developed an innovative hypothesis of an etiological relationship between non-EOE EGIDs and pediatric intestinal surgeries, raising the question as to whether the origin of non-EoE EGIDs could be from an early intrauterine onset with possible evolution to surgical conditions in the natural course of the disease. However, this is not to be verified by this study alone and further research is needed before confirming such a presumption.

On the other hand, further evidence was found that corroborated the presence of tissue eosinophils in the study population. More than half of the patients had different levels of tissue fibrosis in their obtained intestinal tissue. Since the presence of eosinophils leads to the secretion of transforming growth factor-beta and a number of other related cytokines which, in turn, cause fibrosis as the final stage of chronic inflammation [20,21], it could be assumed that fibrosis might stem from previous eosinophilic inflammations and non-EoE EGID. Additionally, the histological assessments of six patients (8.3%) revealed degranulated eosinophils and multi-nucleated cells, known as suggestive diagnostic criteria of non-EoE EGIDs [22]. Eosinophils were also detected in the muscular and serosal layers of the surgically excised tissues in more than 97% of the patients. Muscular and serosal layers are considered abnormal tissues in case of the existence of eosinophils in the GI tract, indicating the presence of non-EoE EGID [22].

Due to the normal presence of hemostatic eosinophils in the lower parts of gastrointestinal tract as well as the lack of consensus on the cut-off number of tissue eosinophils, non-EoE EGIDs, cannot still be diagnosed with high levels of certainty [23]. Favorably, a histological system has been developed for eosinophilic esophagitis that scores eight pathological signs including eosinophil density, eosinophil abscess (accumulation of more than 4 eosinophils) and basal cell hyperplasia [24]. Establishing such scoring system for pathological tissue changes, as well as accumulation of eosinophils in the tissue, is essential for more accurate and timely diagnosis of the disease.

Additionally, it is safe to assume that only counting the number of tissue eosinophils does not seem to be sufficient for the purpose of diagnosis, and therefore more clinical and pathologic studies are required to elucidate the diagnosis. Apart from the challenges in identifying tissue eosinophilia [25], such as the problems with measuring eosinophils in the acute diagnosis of non-EoE EGID, our recommendation is considering a combination of the patients' chronic and recurrent clinical symptoms, the subtle evidence of the presence of eosinophils in tissues (in forms of fibrosis, fistula, presence of eosinophils in layers other than mucosa), macroscopic features of GI tissues (such as nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and eosinophilic abscess) along with the measurements of eosinophil cytokines (such as MBP ,ECP, Eotaxin) for a precise diagnosis.

Remarkably, the frequency of non-EoE EGID in the patients diagnosed by the conventional method in the present study was about 13.9% which is far more than the prevalence of non-EoE EGID in general population (with a prevalence of 2.5/100,000) [19]. This higher prevalence of non-EoE EGID in our study population along with other evidence confirming tissue eosinophilia (in more than 97% of the patients) raises this question as to whether there was a real cause and effect relationship between non-EoE EGID and abdominal surgical conditions. In addition, peripheral blood eosinophilia in more than 63% to 70% of the patients as well as positive skin prick test results with “egg” as the most common food allergen in 43% of the patients may indicate other supportive evidence of this causality and highlight the role of allergy as an etiopathological factor in our study population.

The allergic nature of non-EoE EGIDs has been earlier expressed by Spergel JM et al. (26), and the immunological mechanism in delayed food allergic reactions are predominantly non-immunoglobulin E-mediated [27].

A few studies have reported the allergic basis of some surgical conditions such as recurrent NEC (e.g., in a boy secondary to allergic enterocolitis due to cow's milk protein allergy) [28] and intussusception in both pediatric and adult patients resulting from eosinophilic enteropathy [29, 30]. In one study, Yamada et al. [31] recommended screening and treatment of EoE in patients with esophageal stenosis/or atresia.

Due to the above-mentioned nature of allergy in inducing non-EoE EGIDs, non-invasive interventions including dietary elimination and elemental diets have shown promising effects in both children and adults with non-EoE EGIDs [7,32,33]. Elemental and six-food eliminating diets are the most effective treatments in 90.8% and 72.1% of the patients with EGID, respectively [32]. This mode of therapy alongside systemic and topical corticosteroids may reduce surgical interventions and their potential complications as well as the burden of the disease on both the patients and health system.

As with the majority of studies, the design of the current study is also subject to limitations. Firstly, there was no ther choice, but to re-evaluate the patients’ tissues that were previously collected during the operation. This might negatively have influenced the finding of eosinophils by taking the sample from inappropriate necrotic sites leading to inaccurate and inconclusive pathologic results regarding eosinophils and other inflammatory cells. In addition, immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay as a reliable method to trace the presence of eosinophil-related proteins and cytokines [34] was not implemented in this study either. Another possible source of error was taking biopsies from fibrotic tissues lacking eosinophils because of their fibrotic nature, which was reported in more than 50% of the patients as a sign of chronic eosinophilic inflammation, bleeding or necrosis.

Conclusion

Currently, there are no consensus guidelines, pathognomonic symptoms or laboratory tests for the diagnosis of non-EOE EGIDs. However, clinical manifestations, positive family history of allergies and positive skin prick tests for food allergens may provide useful clues in the diagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs. Our work has led us to conclude that non-EoE EGIDs should be considered in the context of severe relapsing GI complications requiring urgent and/or emergent surgical interventions (except traumatic and cancerous indications), particularly in those without a convenient response after surgeries. Under such circumstances, tissue samples obtained from GI surgeries should be reviewed and scrutinized for eosinophils. Other abnormal, additional findings in the histological assessment of non-EoE EGIDs may include the presence of eosinophils in muscular and serosal layers, degranulated eosinophils, and fibrosis. Samples that are positive for eosinophils may indicate non-EoE EGID in patients, so if treated appropriately in terms of food allergy and timely use of anti-inflammatory medications, it may potentially result in the relief of the symptoms, without further need for surgical procedures.

This study is the first step towards suggesting the surgical complications of delayed diagnosis and management of non-EoE EGIDs in the natural course of this group of disorders, so if diagnosed and treated in a timely manner, such surgeries might not ever be required in some patients. Further studies need to be carried out prospectively in larger populations with specific laboratory studies enabling statistical analysis. IHC staining as well as detection of the eosinophil-driven cytokines, eosinophil specific or secondary granules in addition to direct eosinophil counts, are needed in order to increase the probability of identification of tissue eosinophilia.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the experiments were approved by the local ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the reference No. of IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1398.501 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained from the patients and/or their caregivers/parents for their participation and article publication.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by the Pediatric Surgery Research Center, Mofid Children's Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Author Contributions

SE: interpretation of data, designing the work, drafting the work. SD, MKA: acquisition and interpretation of data, designation of the work MR: acquisition of data, and revision of the manuscript. MRS: acquisition and interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript. NS: drafting and revision of the work. MM: substantial contributions to the conception, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Gonsalves N. (2019). Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 57(2):272-285.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Abonia JP, Alexander JA, Arva NC, Atkins D, et al. (2022). International consensus recommendations for eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease nomenclature. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology. 20(11):2419-2420.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hiremath G, Dellon ES. (2018). Commentary: Individuals affected by Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders Have Complex Unmet Needs and Experience Barriers to Care. Journal of rare diseases research & treatment. 3(2):34.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Lucendo A. (2008). Immunopathological mechanisms of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Allergologia et immunopathologia. 36(4):215-227.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hogan SP, Rothenberg ME. (2006). Eosinophil function in eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders. Current allergy and asthma reports. 6(1):65-71.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jaffe JS, James SP, Mullins GE, Braun-Elwert L, Lubensky I, Metcalfe DD. (1994). Evidence for an abnormal profile of interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and γ-interferon (γ-IFN) in peripheral blood T cells from patients with allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Journal of clinical immunology. 14(5):299-309.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kagalwalla AF, Wechsler JB, Amsden K, Schwartz S, Makhija M, Olive A, et al. (2017). Efficacy of a 4-food elimination diet for children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 15(11):1698-1707.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Reed C, Woosley JT, Dellon ES. (2015). Clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and resource utilization in children and adults with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Digestive and Liver Disease. 47(3):197-201.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mansoor E, Abou Saleh M, Cooper GS. (2017). Prevalence of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis in a population-based study, from 2012 to 2017. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 15(11):1733-1741.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hiremath G, Kodroff E, Strobel MJ, Scott M, Book W, Reidy C, et al. (2018). Individuals affected by eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have complex unmet needs and frequently experience unique barriers to care. Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology. 42(5):483-493.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Licari A, Votto M, D'Auria E, Castagnoli R, Caimmi SM, Marseglia GL. (2020). Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in children: a practical review. Current Pediatric Reviews. 16(2):106-114.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Huang F-C, Ko S-F, Huang S-C, Lee S-Y. (2001). Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with perforation mimicking intussusception. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 33(5):613-615.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sandrasegaran K, Rajesh A, Maglinte DD. (2006). Eosinophilic gastroenteritis presenting as acute abdomen. Emergency Radiology. 13(3):151-154.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Siahanidou T, Mandyla H, Dimitriadis D, Van-Vliet C, Anagnostakis D. (2001). Eosinophilic gastroenteritis complicated with perforation and intussusception in a neonate. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 32(3):335-337.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Butler EK, Tran TM, Nagarajan N, Canner J, Fuller AT, Kushner A, et al. (2017). Epidemiology of pediatric surgical needs in low-income countries. PloS one. 12(3):e0170968.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dhaliwal J, Tobias V, Sugo E, Varjavandi V, Lemberg D, Day A, et al. (2014). Eosinophilic esophagitis in children with esophageal atresia. Diseases of the Esophagus. 27(4):340-347.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Food allergy in under 19s: assessment and Diagnostic.

Publisher | Google Scholor - DeBrosse CW, Case JW, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Rothenberg ME. (2006). Quantity and distribution of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract of children. Pediatric and developmental pathology. 9(3):210-218.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Zhang M, Li Y. (2017). Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: A state‐of‐the‐art review. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 32(1):64-72.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Li-Kim-Moy JP, Tobias V, Day AS, Leach S, Lemberg DA. (2011). Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis and hyalinization are features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 52(2):147-153.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Thaker AI, Melo DM, Samandi LZ, Huang R, Park JY, Cheng E. (2021). Esophageal fibrosis in eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 72(3):392-397.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hurrell JM, Genta RM, Melton SD. (2011). Histopathologic diagnosis of eosinophilic conditions in the gastrointestinal tract. Advances in anatomic pathology. 18(5):335-348.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Collins MH. (2009). Histopathology associated with eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 29(1):109-117.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Collins MH, Martin LJ, Alexander ES, Boyd JT, Sheridan R, He H, et al. (2017). Newly developed and validated eosinophilic esophagitis histology scoring system and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Diseases of the Esophagus. 30(3):1.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kuang FL. (2020). Approach to patients with eosinophilia. Medical Clinics. 104(1):1-14.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Spergel JM, Beausoleil JL, Mascarenhas M, Liacouras CA. (2002). The use of skin prick tests and patch tests to identify causative foods in eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 109(2):363-368.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Cianferoni A. (2020). Non-IgE mediated food allergy. Current Pediatric Reviews. 16(2):95-105.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Srinivasan P, Brandler M, D'Souza A, Millman P, Moreau H. (2010). Allergic enterocolitis presenting as recurrent necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm neonates. Journal of Perinatology. 30(6):431-433.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shin WG, Park CH, Lee YS, Kim KO, Yoo K-S, Kim JH, et al. (2007). Eosinophilic enteritis presenting as intussusception in adult. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 22(1):13.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bramuzzo M, Martelossi S, Villanacci V, Maschio M, Costa S, Ventura A. (2016). Ileoileal intussusceptions caused by eosinophilic enteropathy. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 62(6):e60.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yamada Y, Nishi A, Watanabe S, Kato M. (2015). Esophageal eosinophilia associated with congenital esophageal atresia/stenosis and its responsiveness to proton pump inhibitor. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135(2):AB45.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Arias Á, González-Cervera J, Tenias JM, Lucendo AJ. (2014). Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 146(7):1639-1648.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Okimoto E, Ishimura N, Okada M, Mikami H, Sonoyama H, Ishikawa N, et al. (2018). Successful food-elimination diet in an adult with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. ACG case reports journal. 5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, Covey S, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, et al. (2014). Markers of eosinophilic inflammation for diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis and proton pump inhibitor–responsive esophageal eosinophilia: a prospective study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 12(12):2015-2022.

Publisher | Google Scholor