Research Article

Demography of Leprosy Patients Presenting with Altered Skin Pigmentation in State Capital of North India

1Department of Microbiology, Integral Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, Integral University, Lucknow, UP, India.

2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Allahabad, Allahabad, U.P, India.

*Corresponding Author: Siddharth Prakash, Department of Microbiology, Integral Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, Integral University, Lucknow, UP, India.

Citation: Prakash S., Saquib M., Sharma B. (2024). Demography Of Leprosy Patients Presenting with Altered Skin Pigmentation in State Capital of North India. Scientific Research and Reports, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 1(6):1-11. DOI: 10.59657/2996-8550.brs.24.022

Copyright: © 2024 Siddharth Prakash, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: July 03, 2024 | Accepted: October 21, 2024 | Published: November 18, 2024

Abstract

Background and objectives: Regardless of improvements in all branches of medical disciplines, leprosy continues to be a problem for the healthcare systems in nations like India. Our research will evaluate the demographic profile and microscopic status of patients who present with a clinical picture of leprosy, with an emphasis on altered skin pigmentation among the suburban residents of a state capital in northern India, who are visiting a tertiary care dermatology OPD.

Materials and Methods: Samples were collected by slit skin smear preparation from 7 sites (both ear lobes and both eyebrows, chick, chin and edge of the lesion). Stained with modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain and examined at 1000 X magnification under oil emersion.

Results: Out of 44 cases only 9 were microscopically positive (20.45%). The average bacteriological and morphological index of seven sites was 2+ and 70% with hyperpigmentation in 2 and hypopigmentation in 7 patients. In positive patients 7 were males and 2 were females, only one patient was under weight and average body mass index was 20.76 kg/m2, 6 patients (5 males and 1 female) were urban residents and 3 patients (2 males and 1 female) were rural residents. Some patients arrived late due to social stigma, and many patients had irregular checkups and were not taking medications on a regular basis, resulting in failure in prognosis.

Conclusion: It was observed that leprosy caused hypopigmentation in majority of patients and hyperpigmentation in relatively lower number of patients. Furthermore, the use of more advanced diagnostic modalities, such as PCR, which found a greater number of initial-stage cases when slit skin smear tests were negative, can enhance the low positivity rate of suspected patients by conventional microscopic methods.

Keywords: leprosy; hansen’s disease; hypopigmentation; hypermentation; slit skin smear

Introduction

Hansen's disease, widely known as leprosy, primarily affects men [1] One of the old and chronic diseases presents with erythematous, hypo- or hyperpigmented skin lesions, thickened, painful peripheral nerves, muscle weakness, and eventually paralysis of the hands and feet [2]. Mycobacterium leprae, obligate intracellular pathogen, prefers temperature below 370C to grow [3]. M. leprae has a preference for macrophages as well as Schwann cells found in the peripheral nerves [4]. This bacterium has curved ends, measures from 1 to 8 µm × 0.3 µm and is weakly acid-fast. Although it is curable, nerve damage and physical deformity cannot be undone [5].

The two widely used methods of classification for leprosy patients are Ridley-Jopling method and the World Health Organization's classification. Bacteriologic index, histopathologic characteristics, and clinical signs are all combined across Ridley-Jopling classification method. It makes it easier to categorise various leprosy subtypes along a spectrum, such as tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, mid-borderline, borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Patients which are yet to experience an immune response mediated by cells to bacilli and who may eventually progress to tuberculoid or lepromatous stage are referred to as having indeterminate leprosy [6-11].

In 2016, the World Health Organization announced a five-year "Global leprosy strategy 2016-2020" aimed at speeding the road to a world without leprosy. The campaign is built around three fundamental components: increasing government involvement, collaboration, and communication; preventing leprosy and its challenges; and preventing inequality while encouraging acceptance. At the end of 2016, the worldwide prevalence was more than 170,000, with a documented prevalence of 0.23 per 10,000 citizens, a decrease from 2015. The number of noncommunicable diseases for the year was approximately 210,000, a slight increase over 2015. These global statistics have been calculated on the information provided by more than 140 nations from various parts of the world [12].

The tactics and guidelines for the National Leprosy Eradication Programme in India happen to be designed at the national level, and states and union territories carry out the programme's implementation, sponsored by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of the Indian government. India attained EPHP in the last month of 2005 with an overall prevalence of approximately 0.01%, while in 2016 it was even lower at 0.0066%. One among the 22 nations that account for ninety five percent of the collected data on leprosy worldwide, India persists as the source to about sixty percent of the fresh cases identified internationally annually. In the year 2016, about 34000 newly identified cases of leprosy in areas with high endemicity were discovered as a result of the NLEP's innovative Leprosy Case Detection Campaign strategy, constituting twenty-five percent of yearly reported cases. As far as the programme is concerned, Orissa, Delhi, Chandigarh and Lakshadweep are states and territories where the prevalence is more than one per 10,000 people [12].

Regardless of developments in every field related to medical sciences, leprosy is still a problem for healthcare in nations like India. In our study we have determined the microscopic status of patients presenting with clinical picture of leprosy with special emphasis on altered skin pigmentation in the suburban population of a state capital in North India attending a tertiary care Dermatology OPD.

Materials and methods

From January 01, 2023 to May 31, 2023, patients visiting the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary care facility in Lucknow participated in an observational study to determine the prevalence and characteristics of dermatological conditions. A review of medical records and direct observation of patient consultations was used to gather data.

Sample Collection

Through telephonic and verbal interviews with patient’s consent, demographic data such as age, height, weight, and sex, as well as residence, education, and occupation, and clinical data such as family history, medical history, deformity, site and size of lesion, type of pigmentation, inflammatory findings, and sensory loss, were collected from suspected cases of leprosy.

Slit Skin Smear

Samples were taken from 7 sites (both ear lobes and both eyebrows, chick, chin and edge of the lesion). The preferred location was cleaned with ethyl alcohol, followed by the site being tightly compressed to stop bleeding with the nondominant hand. A 5 mm long by 3 mm deep incision was made using a size 15 sterile scalpel blade while maintaining finger pressure. The cut was deep enough to penetrate the dermis. Wiped away any potential blood or lymph exudates before repeatedly scraping the wound in the same direction while rotating the blade at an angle to collect tissue fluid and pulp on one side of the blade. The collected material was then smeared on a glass slide in a circular motion from the inside to the outside until it is about 8 mm in size. Finally, the smear was fixed over a flame.

Modified Ziehl-Neelsen Stain

The slide was covered with 1

Results

Data and sample of 44 patients were collected in 6 months, 34 interviews were conducted face to face and 9 were telephonically interviewed. Out of 44, 36 patients were males and 8 were females.

The most common age group was between 18 to 30 years and the least common age group was between 66 to 78 years. Median age is 35, mode is 27 (appeared 4 times) and range is 72.

Highest BMI was 30.2 and lowest BMI was 17. Average of BMI of total patients was 20.60 whereas, average BMI of male and females was 20.50 and 24.36, respectively. Analysing body mass index of patients, 38 patients had normal weight, 4 patients were underweight, and only 2 patients were overweight. The median of BMI was 20.15, mode 19.4 (appeared 5 times) and range 13.2.

14 patients (11 males and 3 females) were illiterate, 21 patients (18 males and 3 females) had secondary and below secondary education, and 9 patients (7 males and 2 females) had higher education. While 30 patients were unemployed and 14 patients were employed with average salary of 20000 Rupees per month. Out of 44 patients, 24 patients were from urban area and 20 patients were from rural area. The duration of illness of patients ranged from 1 months to 2.5 years, none of the patients had any family history of leprosy, only 2 patients faced infections other than leprosy, one with oral ulcers and other with Tinea corporis.

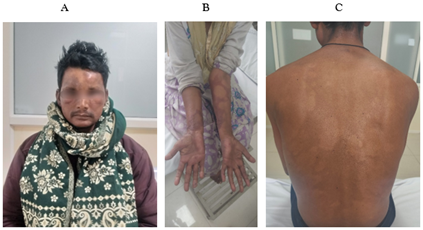

Figure 1: A. Madarosis and infiltration on face; B. Hypopigmented lesions on forearm; C. Hypopigmented lesions on back.

Deformities were observed in only 6 patients, 5 with clawing of hands and one with madarosis. Lesions were present all over body in patients in which back was most common site (17 patients), Forearm was second most common site (9 patients), followed by lesions on hands (5 patients) (Figure 1 A to C). The smallest lesion observed was 1X1 centimetres and biggest was 10X4 centimetres. Inflammation was seen in 15 patients, sites of inflation were mostly elbow, forearm, and arm. The ratio of hyperpigmentation to hypopigmentation and absence to presence of sensory loss was 7:37 and 4:7, respectively.

Clinical staging of some patients lied between two types of leprosy such as: BL/LL, BT/LL. Borderline Tuberculoid leprosy (40.90%) was observed in majority of patients, BT/LL was in 11.36%, LL type 2 reaction and BT/LL was 9.09%, LL was 6.81%, and Intermediate leprosy (2.27%) and Borderline lepromatous leprosy (2.27%) was least observed (Table 1).

Table 1:Clinical staging in suspected patients

| Clinical Staging of Patients | Number of Cases |

| BT | 18 |

| BT/LL | 4 |

| BL | 2 |

| BL/LL | 5 |

| LL | 3 |

| IL | 1 |

| BT Type 1 Reaction | 2 |

| BT Type 2 Reaction | 2 |

| BL Type 2 Reaction | 1 |

| LL Type 2 Reaction | 4 |

| PNL | 2 |

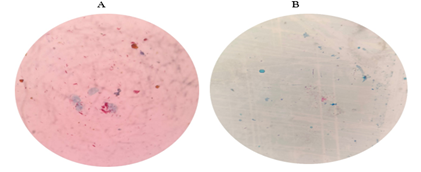

Positive smear of the bacteria is shown in Figure 2. The bbacteriological and morphological index of positive cases with clinical stages are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2: Positive smear showing Acid Fast Bacilli : A. BI-+5; B. BI-+3.

Table 2: Bacteriological and morphological index of positive cases with clinical staging

| Average Bacteriological Index of seven sites | Average Morphological Index of seven sites | Clinical Staging |

| 2+ | 10-20% | LL Type 2 Reaction |

| 5+ | 80-90% | BT |

| 3+ | 80-90% | BL |

| 1+ | 70-80% | BL Type 2 Reaction |

| 1+ | 80-90% | LL Type 2 Reaction |

| 2+ | 70-80% | LL Type 2 Reaction |

| 1+ | 50-60% | LL |

| 2+ | 70-80% | BL/LL |

| 3+ | 80-90% | BT/LL |

Out of 44 cases only 9 were microscopically positive (20.45%), average bacteriological and morphological index was 2+ and 70% on both sites with hyperpigmentation in 2 and hypopigmentation in 7 patients (Table 2; Figure 2). Lepromatous leprosy was most observed in positive cases. In positive patients 7 were males and 2 were females, only one patient was underweighting and average body mass index was 20.76 kg/m2, 6 patients (5 males and 1 female) were urban residents and 3 patients (2 males and 1 female) were rural residents. Sensory loss was seen in three patients and two patients had deformity, whereas inflammation was observed in 5 patients.

Discussion

Leprosy was first described as a chronic, non-fatal infectious disease caused by M. leprae in ancient Indian texts from the sixth century BC. Since the first meeting of the WHO's Leprosy Expert Committee in 1956, its prevalence has been declining globally. However, there are still places where leprosy is endemic, like India. Our study aimed to find the proportion of patients with altered skin pigmentation, whose primary cause is leprosy and to study their demographic makeup.

The immune system's reaction to a variety of diseases, such as M. leprae, is significantly influenced by the state of nutrition and body mass index is a very frequently employed metric to evaluate the state of nutrition. In one study, the majority of patients (30, 60%) had a normal BMI, and in seven patients (14%), it was less than 18.5 with a male to female ratio of 3.1 [16]. In our study, 38 patients had normal weight (BMI between 18.4 and 25), four were underweight (BMI less than 18.5), and only two were overweight (BMI greater than 25), with a male to female ratio of 4:5:1.

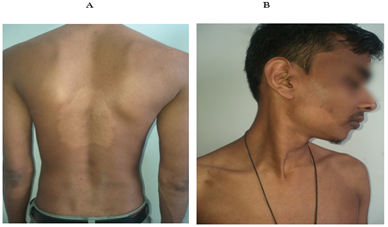

In contrast to our study, where the ratio of hyperpigmentation to hypopigmentation and the absence of sensory loss were 7:44 and 4:7 (Figure 3), there were 8 men and 4 women, the majority in their second decade (mean age 19.1±8.05 years), presented with hypopigmented macules most frequently on the upper limbs for a mean duration of 6.33 ± 5.10 months [17].

Figure 3: Hypopigmented patch on deltoid.

In a comparative study, erythematous plaque was the most common presentation (74.44%), followed by hypopigmented patch (20%) and nodules (14.44%), on extremities (62.22%), trunk (45.55%), and 17.78% presented with generalized lesion (all over body) including face [18]. In contrast, in our study, lesions were present on all parts of the body, with the back being the most common (17 patients), forearm being the second most common (9 patients) and face being the least; the elbow, forearm, and arm were the most common sites of inflation; the smallest and the largest lesions were 1 x 1 and 10 x 4 cm, respectively (Figure 4 A and B).

Figure 4: A-Hypopigmented patch on back B- Hypopigmented patch over mandible.

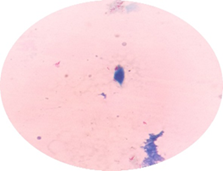

In our investigation, out of 44 cases, only 9 were microscopically positive (20.45%), only one patient in the group of positive patients (7 men and 2 women) was underweight, the average bacteriological and morphological index was 2+ and 70% on all sites (Figure 5), while another study found that 28 (30.77%) of 91 suspected cases were positive for acid-fast bacilli indicative of M. leprae. There were 64 men in total, 20 of them (71.43%) were positive; and 8 out of 27 female suspects (28.57%) were positive for AFB. The male to female ratio was 2.37:1. The maximum number of positive cases i.e.14 (50%), was observed in the age group 31-50 years [19].

Figure 5: AFB positive smear in a suspected patient of leprosy, BI: +3.

The results of our investigation showed that the bacillary index of slit skin smear (BIS) was positive in 20.45% of patients. However, in a different study, the bacillary index of granuloma (BIG) was consistently positive when the bacillary index of slit skin smear (BIS) was positive [20]. Three borderline tuberculoid leprosy individuals with five lesions who were treated with the PB regimen had positive bacillary index of granulomas, but all three cases had negative bacillary indices of slit skin smears [20].

Limitations

Our study was limited by a small sample size, and we did not perform biopsy and staining. A comparison of microscopic findings with histopathological findings could have given us more information about the positive cases. To confirm these findings, additional investigations and a larger sample size is required.

References

- Gupta, S. K. (2015). Histoid leprosy: Review of the literature. International Journal of Dermatology, 54(11):1283-1288.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Eichelmann, K., González González, S. E., Salas-Alanis, J. C., & Ocampo-Candiani, J. (2013, September). Leprosy: An update: Definition, pathogenesis, classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliográficas, 104(7):554-563.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Draper, P. (1983, March). The bacteriology of Mycobacterium leprae. Tubercle, 64(1):43-56.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Singh, P., & Cole, S. T. (2011). Mycobacterium leprae: Genes, pseudogenes and genetic diversity. Future Microbiology, 6(1):57-71.

Publisher | Google Scholor - White, C., & Franco-Paredes, C. (2015). Leprosy in the 21st century. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 28(1):80-94.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Maymone, M. B. C., Laughter, M., Venkatesh, S., Dacso, M. M., Rao, P. N., Stryjewska, B. M., & et al. (2020). Leprosy: Clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 83(1):1-14.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ridley, D. S., & Jopling, W. H. (1966). Classification of leprosy according to immunity: A five-group system. International Journal of Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, 34(3):255-273.

Publisher | Google Scholor - WHO Chemotherapy Study Group. (1995). Indian Journal of Leprosy, 67(3):350-352.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pin, D., Guerin-Faublee, V., Garreau, V., & et al. (2014). Mycobacterium species related to M. leprae and M. lepromatosis from cows with bovine nodular thelitis. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 20(12):2111-2114.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Fonseca, A. B., Simon, M. D., Cazzaniga, R. A., & et al. (2017). The influence of innate and adaptive immune responses on the differential clinical outcomes of leprosy. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 6(1):5.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Modlin, R. L. (1994). Th1-Th2 paradigm: Insights from leprosy. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 102(6):828-832.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Rao, P. N., & Suneetha, S. (2018). Current situation of leprosy in India and its future implications. Indian Dermatology Online Journal, 9(2):83-89.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mohan, N., Sunil, M., Akhil, G., Priya, S. K., Vijayakumar, V., Vineetha, M., & et al. (2023, July-December). Modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining for Mycobacterium leprae. Journal of Skin and Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 5(2):120-122.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gautam, M., & Jaiswal, A. (2019). Forgetting the cardinal sign is a cardinal sin: Slit-skin smear. Indian Journal of Paediatric Dermatology, 20(4):341-344.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Patil, A. S., Mishra, M., Taiwade, P., & Shrikhande, S. (2020). A study of indices in smear positive leprosy in the post-elimination era: Experience at a teaching tertiary care centre. MAMC Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(3):211-215.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jindal, R., Nagrani, P., Chauhan, P., Bisht, Y. S., Sethi, S., Roy, S., & et al. (2022). Nutritional status of patients with leprosy attending a tertiary care institute in North India. Cureus, 14(3):e23217.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Bhatia, R., Gupta, V., Arava, S., Khandpur, S., & Ramam, M. (2020). Macular hypopigmentation, hair loss and follicular spongiosis: A distinct clinicopathological entity. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, 86(4):386-391.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Gupta, N., Kumawat, K., Gupta, D., Paliwal, V., Khan, I., Saharan, N., & et al. (2021). A comparative analysis of expression of leprosy according to age group: Area of focus for eradication. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research, 12(11):43618-43623.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kalita, J. M., Nag, V. L., & Yedale, K. (2020). Spectrum of leprosy among suspected cases attending a teaching hospital in Western Rajasthan, India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(6):2781-2784.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Kumaran, S. M., Bhat, I. P., Madhukara, J., Rout, P., & Elizabeth, J. (2015). Comparison of bacillary index on slit skin smear with bacillary index of granuloma in leprosy and its relevance to present therapeutic regimens. Indian Journal of Dermatology, 60(1):51-54.

Publisher | Google Scholor