Review Article

Confirmatory factor analysis of the corporate governance of universities around the SDGs

- Jorge E. Chaparro Medina 1*

- Cruz García Lirios 2

- Isabel Cristina Rincón Rodríguez 3

- Julio E. Crespo 4

- Javier Carreón Guillen 5

- Marcela Patricia Estrada Arango 6

- Omar Alejandro Afanador Ortiz 7

- Jairo Eduardo Vargas Álvarez 7

1University of Research and Development UDI, Bucaramanga, Colombia. 2University of Health, CDMX, Mexico. 3University of Research and Development UDI, Bucaramanga, Colombia. 4University of Los Lagos, Osorno, Chile. 5National Autonomous University of Mexico, CDMX, Mexico. 6University of Research and Development UDI, Bucaramanga, Colombia. 7University of Research and Development UDI, Bucaramanga, Colombia

*Corresponding Author: Jorge E. Chaparro Medina,University of Research and Development UDI, Bucaramanga, Colombia. 2University of Health, CDMX, Mexico.

Citation: J.E.C. Medina, Cruz G. Lirios, I.C.R. Rodríguez, Julio E. Crespo, Javier C. Guillen, et al. (2024). Confirmatory factor analysis of the corporate governance of universities around the SDGs. International Journal of Medical Case Reports and Reviews, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 3(6):1-7. DOI: 10.59657/2837-8172.brs.24.068

Copyright: © 2024 Jorge E. Chaparro Medina, this is an open-accsess article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: October 14, 2024 | Accepted: October 25, 2024 | Published: November 05, 2024

Abstract

Corporate governance has been identified as a result of a context in which organizations seek to maximize benefits from their image about the parties that make them up. Considering the university environment, this work aimed to compare the theoretical structure of governance with a series of empirical observations. A cross-sectional, psychometric, confirmatory, and correlational study was conducted with 100 students from a public university in central Mexico. Six of the ten dimensions that explained between 16% and 86% of the variance related to corporate governance are confirmed. The incidence of other indicator factors that would increase the percentage of variance is recognized. It is recommended that the study and the sample be extended to confirm the structure.

Keywords: confirmatory factor analysis; covid-19; corporate governance; sdgs

Introduction

Corporate governance refers to the system by which companies are directed and controlled (Husted & Serrano, 2002). Throughout history, corporate governance has evolved in response to the changing needs of companies, investors, and society. During the Industrial Revolution, the formation of large modern corporations began to take shape. Companies were formed primarily to exploit economies of scale during this period. As companies grew, owners (shareholders) began to hire professional managers to manage daily operations. This separation of ownership and control was one of the earliest concerns in corporate governance (Crespo et al., 2022). As companies grew, owners could no longer directly control managers (Davis, 2005). In this context, agency theory emerged, which describes the conflict of interests between owners (principals) and managers (agents). Managers may make decisions that do not necessarily benefit shareholders. Laws and regulations began to be developed that protected the interests of shareholders, ensuring that managers act in the best interests of the company's owners. The Great Depression of 1929 was a turning point in corporate governance, highlighting the need for tighter regulation and oversight of companies (Agosin & Pastén, 2003). Creating the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 marked an important milestone in the United States' stock market regulation and corporate transparency. With the collapse of several large companies due to mismanagement and fraud, there was a renewed interest in corporate governance beginning in the 1980s and 1990s. Codes and recommendations began to be created on how companies should be run to avoid problems. An important example was the 1992 Cadbury Report in the United Kingdom, which laid the foundations for many modern governance principles, such as independent boards of directors. Corporate scandals such as Enron (2001) and WorldCom in the US demonstrated the need to strengthen rules on auditing and internal control of companies (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). In response, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) was enacted in 2002, requiring greater transparency and accountability in US corporations. The global financial crisis 2008 again highlighted the importance of good corporate governance, particularly for financial institutions. New reforms were implemented to prevent high-risk behavior in companies. Corporate governance has evolved to include social responsibility and sustainability (Yermack, 2017). Investors and the general public demand that companies pursue short-term profits and contribute positively to the environment and society. The ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) concept has gained prominence and is now a critical factor in assessing a company’s performance and responsibility. Board diversity, transparency, and business ethics are central issues in modern governance. The use of technology in governance, such as artificial intelligence and data analytics systems, is redefining how information and decision-making are managed in companies.

Corporate governance has evolved from a simple approach to management and control to a complex system involving multiple actors and aspects, such as ethics, social responsibility, and sustainability (Pargendler, 2016).

Table 1: Comparison of corporate governance dimensions

| Dimension | Before the pandemic | After the pandemic |

| Governance structure | Predominantly hierarchical, with a rector, board of directors, and faculties. | More flexible and adaptive approaches with less centralized structures. |

| decision making | Generally carried out by collegiate bodies, long and formal processes. | Faster, more agile decision-making driven by the crisis. |

| Technology and digitalization | Limited use of technologies for teaching and administration. | Mass adoption of technological platforms for teaching, research, and management. |

| Distance education | Secondary option, not significantly developed. | Consolidated hybrid model, with virtual tools as a central part. |

| Transparency and accountability | Transparency policies, but in many cases, are limited to formal compliance. | Greater demand for transparency, with real-time accountability, thanks to digital technologies. |

| Financial resource management | Traditional financial models are based on tuition fees and government subsidies. | Revenue diversification through online education, partnerships, and blended financing. |

| Sustainability and social responsibility | Focus on social programs, but with limited reach. | Increased focus on sustainability and social responsibility as a core institutional strategy. |

| Participation in the university community | Limited participation of students and teachers in strategic decisions. | Greater involvement of the university community in decision-making processes through digital media. |

| Educational innovation | Moderate innovation based on traditional methods. | Accelerating innovation through artificial intelligence, big data, and new teaching methodologies. |

| Risk management | Risk planning is limited to specific traditional scenarios (economic crisis, security). | A comprehensive risk management approach incorporates the ability to respond to global crises, such as pandemics. |

| Internationalization | Focus on student mobility and international collaboration agreements. | Growth of digital internationalization, virtual cooperation between institutions, and greater global access. |

| Relationship with the labor market | Relationship with the local labour market, adapted to specific needs. | Faster adaptation to global labor demands, with a focus on digital skills. |

| Inclusion and equity | Traditional equity programs focus on admissions policies. | Greater emphasis on digital equity, access to technology, and policies to close social gaps. |

However, their structural composition has yet to confirm the dimensions of corporate governance. Therefore, this paper aims to prove the factorial structure of corporate governance observed in a public university in central Mexico.

Are there significant differences between the corporate governance established in the literature review concerning the observations of this work? The premise on which this work is based suggests differences between the theoretical and empirical dimensions since higher education institutions emphasize the normative part more than the descriptive one.

Methods

Design. A cross-sectional, confirmatory, correlational, and psychometric study was conducted with 100 students from a public university in central Mexico, selected for their affiliation and commitment to the SDGs.

Instrument

The Corporate Governance Scale was used (see Appendix A). It includes the following dimensions: 1) Governance Structure, 2) Decision Making, 3) Resource Management, 4) Financial Strategies, 5) Sustainability, 6) Inclusiveness, 7) Engagement, 8) Innovation, 9) Continuous Improvement, 10) Commitment. The instrument's reliability reached values just above the minimum alpha and omega of 0.700, the adequacy was higher than 0.600, and the sphericity was significant for the validity that ranged between 0.325 and 0.6547.

Procedure

Respondents were informed about the project's objective and those responsible for it. They were told their participation would not be remunerated and their responses to the instrument would not affect their academic status. They were invited to a focus group session to clarify concepts and to a Delphi study for evaluation. The surveys were administered at the university's facilities.

Analysis

The parameters of reliability, adequacy, sphericity, validity, adjustment, and residuals were processed. The hypothesis was contrasted, considering values close to unity except for the residuals.

Appendix A

Survey

Measuring Corporate Governance in Universities Committed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Governance Structure and Decision-Making

To what extent does your university integrate SDGs into its strategic planning and decision-making processes?

A) Fully integrated into all decision-making processes.

B) Partially integrated into some decision-making processes.

C) SDGs are acknowledged but not systematically integrated.

D) SDGs are not currently considered.

How transparent are your university's decision-making processes regarding SDG-related initiatives?

A) Fully transparent and openly communicated to all stakeholders.

B) Transparent but only communicated to specific groups (e.g., faculty, administration).

C) Somewhat transparent but not widely communicated.

D) Not transparent or communicated.

How often does your university's board or governing body review SDG-related goals and progress?

A) Regularly (e.g., annually or biannually).

B) Occasionally (e.g., every few years).

C) Rarely (e.g., ad hoc or occasionally).

D) Never.

Financial Management and Resources

To what extent does your university allocate financial resources to SDG-related initiatives?

A) A significant portion of the budget is dedicated to SDG initiatives.

B) A moderate portion of the budget is dedicated to SDG initiatives.

C) Minimum budget allocation for SDG initiatives.

D) No specific budget for SDG initiatives.

How does your university ensure financial accountability in SDG-related projects?

A) Through regular audits and detailed financial reports specific to SDG initiatives.

B) General financial oversight but no specific focus on SDG projects.

C) Some financial oversight, but accountability is inconsistent.

D) No specific financial oversight for SDG-related projects.

Sustainability and Environmental Governance

To what extent does your university incorporate environmental sustainability into its operations (e.g., energy use, waste management, and procurement)?

A) Fully integrated, with clear policies and measurable goals.

B) Partially integrated, with some policies and goals.

C) Limited integration with ad hoc initiatives.

D) Not integrated.

How does your university track and report its environmental impact on SDG targets (e.g., carbon footprint, energy efficiency)?

A) Comprehensive tracking and regular public reporting.

B) Some tracking with limited reporting.

C) Minimal tracking and no regular reporting.

D) No tracking or reporting.

Stakeholder Engagement and Inclusivity

How actively are students, faculty, and staff involved in shaping the university's SDG-related policies and initiatives?

A) Actively involved at all levels (planning, implementation, and evaluation).

B) Involved primarily in specific initiatives or projects.

C) Limited involvement in policy-making but some participation in activities.

D) Not involved.

How inclusive are your university's governance processes ensuring diverse representation (gender, minority groups) in SDG-related decision-making?

A) Fully inclusive, with structured efforts to ensure diversity.

B) Somewhat inclusive, but diversity is not a primary focus.

C) Limited inclusion, with some representation but no formal processes.

D) Not inclusive or representative.

To what extent does your university collaborate with external stakeholders (e.g., local communities, NGOs, and industry) to advance the SDGs?

A) Extensive collaboration with regular partnerships and joint initiatives.

B) Moderate collaboration, with occasional partnerships.

C) Minimal collaboration with few external engagements.

D) No collaboration with external stakeholders.

Innovation and Continuous Improvement

How does your university promote innovation in addressing the SDGs (e.g., through research, curriculum development, and technology)?

A) Strong emphasis on innovation with dedicated programs and resources.

B) Moderate emphasis, with some programs focused on innovation.

C) Limited emphasis, with few innovative initiatives.

D) No focus on innovation for SDGs.

Does your university have mechanisms for regularly evaluating and updating its SDG-related policies and governance practices?

A) Yes, through formal review processes and continuous improvement strategies.

B) Some mechanisms are in place but not consistently applied.

C) Minimal evaluation of SDG-related policies.

D) No formal evaluation mechanisms.

Overall Commitment to the SDGs

How committed is your university to achieving the SDGs by the 2030 deadline?

A) Fully committed, with clear objectives, strategies, and timelines.

B) Moderately committed, with some objectives and strategies in place.

C) Somewhat committed but lacking clear strategies and timelines.

D) Not committed to the SDGs.

Scoring and Interpretation

For each section, assign points as follows

A = 4 points

B = 3 points

C = 2 points

D = 1 point

Total Score:

50-52 points: Excellent commitment to SDG-related governance.

40-49 points: Strong commitment but with areas for improvement.

30-39 points: Moderate commitment, with several areas needing attention.

Below 30 points: Limited or no commitment to SDG governance.

Appendix B

# Install necessary packages

! pip install pandas odfpy semopy

# Import required libraries

import pandas as pd

from semopy import Model, Optimizer

# Load the data from the .ods file

file_path = '/mnt/data/SEM CFA Governance.ods'

data = pd.read_excel(file_path, engine='odf')

# Display the first few rows to understand the structure

print(data.head())

# Define the CFA model (example with latent variables `Factor1`, `Factor2`)

# Replace 'Factor1' and 'Factor2' with the current factor names and observed variables from your model

model_desc = """

Factor1 =~ observed_variable1 + observed_variable2 + observed_variable3

Factor2 =~ observed_variable4 + observed_variable5 + observed_variable6

# Create and fit the model

model = Model(model_desc)

opt = Optimizer(model)

results = opt.fit(data)

# Print summary of the results

print(model.inspect())

# Show model fit statistics

print ("Model fit statistics:")

print(model.calc_stats())

Results

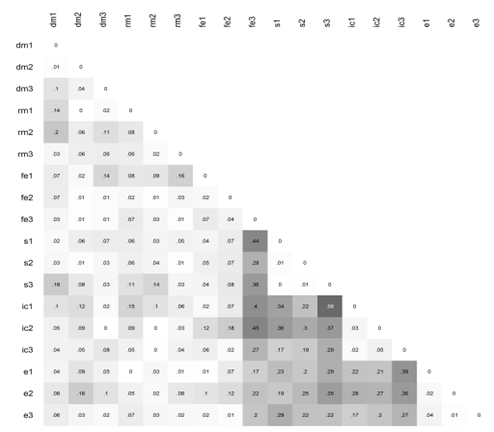

Figure 1: Covariances between corporate governance indicators

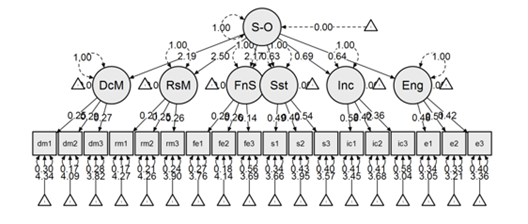

The structural factor analysis specifies the relationships between factors and indicators (see Fig. 2). The values between the indicators and the factors, as well as between the second-order factors and the first-order factor, suggest the confirmation of a six-factor factor structure with 18 indicators that converge on a common factor identified by the literature as university governance.

Figure 2: Confirmatory factor model of university governance

The fit and residual values [x2 = 1054.240 (129 gl) p > 0.0001; GFI = 0.959; RMSEA = 0.000; SRMR = 0.141] suggest that the hypothesis regarding the relative differences between the theoretical structure and the empirical observation of corporate governance is not rejected.

Discussion

This work's contribution to the state of the art lies in establishing a confirmatory factor corporate governance model. The results confirm six of the ten dimensions that explain 16% and 86% of the variance.

The literature on corporate governance has evolved over the years, with various studies focusing on different aspects of this topic (Huang, 2010). The evolution of the economic and institutional scenario highlights the new relationships between large corporations, shareholders, and commissioners. The challenges of implementing the corporate governance model are also explored with a focus on the role of the parceled chambers in this process. Understanding the development of corporate governance in companies emphasizes the conceptual, theoretical, and applied reflections on this topic.

Internal control activities shed light on the importance of internal control from the internal and external audit perspectives as a cause and effect of good governance of accounting reports and tax returns (Williamson, 1988). The empirical relationship between corporate governance and performance, with emphasis on technical efficiency and productivity growth. The association between corporate governance and earnings management in companies highlights the sample of publicly traded companies. The relationship between corporate tax avoidance and the company's value on the stock market.

Family businesses and their concepts, theories, and structures provide insight into this specific aspect of corporate governance (Claessens, 2006). The pillars of corporate governance, such as transparency, fairness, accountability, and corporate responsibility, emphasize the importance of creating a system for the company's management. Overall, the review of the literature on corporate governance covers several dimensions, including the evolution of the economic and institutional scenario, internal control activities, the relationship between corporate governance and performance, earnings management, tax avoidance, and family businesses. These studies contribute to a comprehensive understanding of corporate governance and its implications for organizational development in the Brazilian context.

A transformation involves the participation of rulers and the ruled (Romano, 1996). ECLAC can propose changes, adjustments, transitions, or guidelines, but changes cannot be considered if one or several civil society sectors do not participate directly or indirectly. ECLAC seems to recognize this issue since its 2018 proposal introduces the topic of governance to include the participation of organized society. This initiative reveals an institutional advance by ECLAC since a new Bottom-Up approach is replacing its top-down model. In this sense, artificial intelligence, as a growth perspective in the information society of the region, must be built according to talent training.

Leaders who are trained today in artificial intelligence and have a bottom-up policy will allow the inclusion of sectors (Thomsen, 2004). In this way, ECLAC is moving towards an inclusive transformation of its proposals by considering two axes on which it has little influence, such as governance and artificial intelligence. This is an institutional case in which social demands or the advances of science and technology force it to rethink its objectives for the coming years. ECLAC's institutional learning regarding its proposed policies suggests a global transformation in which intellectual capital and civil sectors acquire institutional and political awareness that allows them to interfere in public affairs. In exchange, civil society must open itself to the interference of its rulers in their private lives. The State, through artificial intelligence itself, must design policies that guarantee the formation of intellectual capital with political solvency to reduce the risks posed by artificial intelligence and the omnipresence of the State in the economy.

In this way, ECLAC can continue to propose public policies. However, if it does not consider the inclusion of civil society, it will not be able to advance one iota in realizing its purposes for the coming years. Even if ECLAC continues to consider the environment as an externality between rulers and the governed, it will be left in the lurch when it learns that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) are a priority over any science, technology, device, or socio-digital network (Aras & Crowther, 2008). The SDGs are the guiding axes of any proposal for growth and development. If any of these SDGs were not met, environmental risks would make the sectors that have acquired the capacity to mobilize and enter into conflict with the State more vulnerable. Suppose any SDG is considered secondary to growth and development based on artificial intelligence. In that case, ecologically conscious users will not be able to adopt any technology that does not include recycling or energy optimization in its processes.

Different from the state of the art, in which corporate governance emerges as a phase of organizational evolution, this paper notes that in educational settings, corporate governance is not so dispersed and is instead guided by axes of commitment, responsibility, decision, sustainability, and innovation. Therefore, it is recognized that the study should be extended to adjust the model and confirm the structure reported in the literature.

Conclusion

This study seeks to define an empirical factor structure for comparison with corporate governance theory. Six of the ten factors have been validated, but further research is necessary. Expanding the sample size to validate all dimensions and enhance the variance explained between the factors and reagents is also recommended.

References

- Agosin, M.R., & Pastén, E. (2003). Corporate governance in Chile. Working Papers (Central Bank of Chile), 209:1-25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Aras, G., & Crowther, D. (2008). Governance and sustainability: Investigating the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Management Decision, 4 (3):433-448.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Claessens, S. (2006). Corporate governance and development. The World Bank Research Observer, 21(1):91-122.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Crespo, J.E., Álvarez Zúñiga, M.A., & Monteverde Sánchez, A. (2022). Gobierno corporativo, educación superior y sostenibilidad en contextos multiculturales. Revista de Filosofía, Venezuela, 39(100):104-113.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Davis, G. F. (2005). New directions in corporate governance. Annu. Rev. Sociol, 31 (1):143-162.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Huang, C.J. (2010). Corporate governance, corporate social responsibility and corporate performance. Journal of management & organization, 16 (5):641–655.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Husted, B.W., & Serrano, C. (2002). Corporate governance in Mexico. Journal of Business Ethics, 37:337-348.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Pargendler, M. (2016). The corporate governance obsession. J. Corp. L., 42:359.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Romano, R. (1996). Corporate law and corporate governance. Industrial and corporate change, 5 (2):277-340.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The journal of finance, 52 (2):737-783.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Thomsen, S. (2004). Corporate values and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society, 4 (4):29-46.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Williamson, O. E. (1988). Corporate finance and corporate governance. The journal of finance, 43 (3):567-591.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Yermack, D. (2017). Corporate governance and blockchains. Review of Finance, 21 (1):7-31.

Publisher | Google Scholor