Research Article

A Nepal Demographic Health Survey Findings on Status of Women Empowerment Using Indicator as Employment Status in Nepal

1MPH, BRAC University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

2MPH, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

*Corresponding Author: Sandesh Bhattarai, MPH, BRAC University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Citation: Bhattarai S, Bishwas S. (2024). A Nepal Demographic Health Survey Findings on Status of Women Empowerment Using Indicator as Employment Status in Nepal. Journal of Women Health Care and Gynecology, BioRes Scientia Publishers. 4(3):1-11. DOI: 10.59657/2993-0871.brs.24.065

Copyright: © 2024 Sandesh Bhattarai, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: September 23, 2024 | Accepted: October 29, 2024 | Published: November 13, 2024

Abstract

Background: Empowering women through increased employment is crucial for sustainable development goals; however, globally, women face economic disparities and limited access to opportunities. In South Asia, including Nepal, low female labor force participation persists due to various challenges, such as gender-based violence, discrimination, and societal norms. This study aimed to investigate the factors influencing women's employment status in Nepal by focusing on education, children, wealth, partners’ education, and other socioeconomic factors.

Method: Data from the 2016 Nepal Demographic Health Survey were obtained through a DHS website. A working dataset was constructed comprising 11 independent variables and was cleaned for analysis. Missing values were addressed, and the statistical analysis plan included descriptive analysis and chi-square tests to examine relationships between variables.

Results: The sociodemographic profile of married women aged 15-49 in Nepal reveals a predominance of male-headed households, urban residency, and secondary education attainment. Unadjusted logistic regression findings indicated significant associations between women's employment status and factors such as age, rural residency, lower education levels, more children, and poorer household wealth. However, multivariate analysis suggested that female-headed households have a slightly lower likelihood of employment. Age and education emerge as key determinants, with older and educated women being more likely to be employed. Provincial disparities are evident, with certain provinces showing increased employment odds, while mobile phone ownership is associated with increased employment likelihood. These findings emphasize the complex interplay of factors influencing women's employment status, underscoring the need to address socioeconomic disparities for enhanced empowerment and economic participation.

Conclusion: The findings reveal a greater prevalence of employment among women than among unemployed individuals, yet disparities persist between male and female employment rates. Women with no education are more likely to be employed in daily waged labor-intensive jobs, indicating a need for targeted interventions to enhance employment opportunities, particularly in disadvantaged regions such as Province 6. The study underscores the association between women's age and education levels with employment status, highlighting the importance of educational attainment in facilitating employment. Moreover, the findings suggest a positive correlation between husbands’ education level and women's employment, emphasizing the significance of household dynamics. Recommendations include the development of employment programs tailored to women's educational backgrounds and vocational training initiatives to enhance their participation in professional sectors, ultimately fostering economic independence and empowerment at the local level.

Keywords: women's employment; economic status; empowerment; female labor force participation; Nepal

Introduction

Empowering women is considered a crucial purist of Sustainable Development Goals [1]. A greater number of women employed is a sign of positivity that a nation is developing and is an asset to the nation. Employment is the source of income for employees or for individuals who are self-employed [2]. Employment status can be a factor in determining the status of empowerment among both men and women, where empowering women through education, access to resources, and decision-making power can lead to increased participation in the female workforce, improving their employment status [2]. Compared with the male population, more than 2.4 billion women worldwide lack economic rights, and the number of women working globally increased significantly from 34% in 1950 to more than 57% [3]. Women's empowerment has been a critical issue in many countries where efforts have been made to ensure that the rights of men and women are equally aimed at ensuring gender equality. Despite these efforts, women continue to face discrimination and inequality in various forms, including limited access to education, healthcare, employment, and political representation [4].

Similarly, South Asia is a region that is diverse in terms of culture, religion, geographical implications, and socioeconomic status. The average FLFP in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Nepal is 23.6%, whereas in developed countries such as China, it is 61% [5]. South Asia has substantially higher unemployment rates than the rest of the world, and there are still considerable barriers preventing women from finding gainful jobs [6]. South Asia has the lowest percentage of FLFP in the world. In low-income families, female employment and participation rates are relatively high [7]. A study showed that employment accelerates women’s empowerment in Nepal [8]. The ILO Nepal states challenges such as the prevalence of gender-based violence and discrimination against marginalized communities of women, including Dalit, Indigenous, and Muslim women, which have adverse effects on employment and empowerment [9]. Due to the many geographical challenges and higher illiteracy rates among females, Nepal has lower employment rates for women than for men. A national-level newspaper, Kathmandu Post, writes that even though there are more men than women in the country who are of working age, there is a significant pay gap between the sexes and a lower employment rate for women [13]. Prevalent patriarchal society thinking leads women to stay inside the home and perform household work rather than go out for jobs. Even girls, mainly in rural areas, are not sent to school, and boys in the same house are enrolled in boarding schools, which shows disparity among females [10]. A study conducted on demographic and socioeconomic determinants of women’s empowerment in Bangladesh showed significant associations between age, division, number of children, education level, and wealth status [11].

The major aim of this study is to identify the factors that influence the employment status of women in Nepal by using the 2016 NDHS survey. A total of 15- to 49-year-old married women were the study population who had or had not been engaged in some form of employment, as employment status is considered a powerful indicator of women's empowerment status.

Methodology

Source of data

The research explores the “status of women’s empowerment in Nepal by using the indicator of employment status”. First, I created a DHS account and emailed USAID’s DHS program to request the dataset for the analysis. I started with the analysis of the dataset to present the findings. The study data were obtained from the Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) 2016, which was performed by the Ministry of Health, Nepal; hence, ethical approval is not needed for the analysis of data from the NDHS. The data files are freely available at https://www.dhsprogram.com/.

Working dataset

I generated the working dataset by separating dependent and independent variables according to my objective containing relevant information. There was a total of 6,288 variables in the Nepal Demographic Health Survey in 2016. From those variables, I selected the 11 independent variables for the study.

I subsequently ran STATA V.17, dropped all the other variables, and retained only the outcome and explanatory variables with the keep (variable code) command. I subsequently added four variables that are associated with employment status and women’s empowerment according to the literature search. Moreover, a weighted sample was taken for study purposes. The weight calculation for the sample size was performed with the following command, where all the generated results are based on weighted calculations.

gen wgt = weight sampleunit/1000000

svyset PSU [pw=wgt], strata (Stratasampledesign)

Once I had generated the working dataset, I cleaned the data by checking for missing values, outliers, and other data quality issues and then analyzed the data to answer the research questions.

Variables and Measurements

The study, based on NDHS 2016 data, investigates the employment status of women in Nepal, with the outcome variable being binary (employed or not). Nine independent variables, including women's education level, number of living children, household wealth quintile, partner's education level, type of residence, partner's occupation, ownership of a mobile phone, etc., are examined. The household wealth quintile indicates socioeconomic status, while education level represents the highest and lowest educational attainment of women and men in the household. The number of children refers to how many children are living in the family. All the measurements and categorizations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Dependent and explanatory variables with their measurements, codes, and labels

| Dependent Variable | |||||

| SN | Name of Variables | Name | Type of Variable | Variable Code | Labels |

| 1 | Respondent currently working | empstatus | Binary Categorical | v714 | Yes “Employed” |

| No “Not-Employed” | |||||

| Explanatory Variables | |||||

| 1 | Sex of household head | sexHHhead | Categorical | V151 | Male |

| Female | |||||

| 2 | Recode the respondent's current age group | Age_cat | Categorical | Recode of V012 | 15-24 |

| 25-34 | |||||

| 35-44 | |||||

| 45+ | |||||

| 3 | Type of place of residence | place type | Categorical | V025 | Urban |

| Rural | |||||

| 4 | Highest women's educational level | womenedulvl | Categorical | V106 | No education |

| Primary | |||||

| Secondary | |||||

| Higher | |||||

| 5 | categorized number of children | Chil_cat | Categorical | Recode of V218 | No children |

| 1-3 Children | |||||

| 4 and more | |||||

| 6 | Wealth index combined | quintile | Categorical | V190 | Poorest |

| Poorer | |||||

| Middle | |||||

| Richer | |||||

| Richest | |||||

| 7 | Recode partner education | Partnered_new | Categorical | No education | |

| Primary | |||||

| Above secondary | |||||

| don’t know | |||||

| 8 | Province | state | Categorical | V024 | Province 1 |

| province 2 | |||||

| province 3 | |||||

| province 4 | |||||

| province 5 | |||||

| province 6 | |||||

| province 7 | |||||

| 9 | Owns a mobile telephone | Mbl phone | Categorical | V169a | Yes |

| No | |||||

| 10 | Women's individual sample weight | Women sample unit | V005 | ||

| 11 | Respondents current age | empstatus | Continuous | V012 | 15 to 49 age group |

| 12 | Primary sampling unit | PSU | V021 | ||

| 13 | Stratification used in the sample | Strat a sampledes | V023 | ||

| 14 | Number of living children | Numb children | Discrete | V218 | 1 to 11 children present |

Sampling Strategy and Data Collection Procedure

The DHS is a five-year cross-sectional survey conducted in Nepal and many other countries. The Central Bureau of Statistics sample frame was employed by the NDHS. The country now has 753 local-level entities with new urban‒rural divisions. The stratified sampling approach employed includes two steps in rural regions and three stages in urban areas. The federal states were divided into urban and rural regions, yielding a total of 14 sample strata. Ward samples were chosen at random in each stratum. In the first step, 383 wards were chosen with a probability proportionate to ward size and independently. In the second stage of urban area selection, one enumeration area (EA) was chosen at random from each sample ward (NDHS, 2016).

The last round of selection involved selecting a specified number of 30 households per cluster with an equal likelihood of systematic selection from the newly constructed household listing. Half of the men and women aged 15 to 49 who lived in chosen houses and were either permanent residents or guests who stayed the night before the survey were eligible to be questioned. To avoid bias, no replacements or adjustments to the preselected households were permitted during the implementation stages. The overall number of respondents (household heads) was 12,862, with 8743 men and 4119 women. There were five types of questionnaires used: household, female, male, biomarker, and verbal autopsy. Before collecting the data, a formal informed consent was obtained. The questionnaire was encoded into a tablet after it was translated from English into Nepali, Maithili, and Bhojpuri. All women between the ages of 15 and 49 were surveyed using a questionnaire [12].

Examine missing values

Dealing with missing values in the NDHS data that I generated for the study required careful consideration, as this can affect the accuracy and reliability of the analysis that is going to be performed. There were no missing values for the outcome or dependent variable. The working dataset shows missing values for the independent variable 2958 on the partner's level of education. Since the missing observations can be due to responses, they cannot or are willing not to provide information to enumerators, and all the participants were married women. Thus, 2958 missing observations related to partner education were included in the group not familiar with the variables.

Statistical analysis plan

To determine the associations and effects of all those independent or explanatory variables on the response variable, appropriate statistical analysis is crucial for the study conducted. To address the research

Questions, the following steps follow:

A descriptive analysis was performed to calculate the percentage and explore the sociodemographic characteristics of currently married women aged 15-49 years who reported engaging in some form of employment; the results are displayed in the graphs.

To examine the relationship between two categorical variables, i.e., the sex of the household head, respondent age group, type of residence, respondent education, grouped number of living children, household wealth quintile, province, and owning a mobile phone, chi-square tests were used to determine the significant associations between those variables and the response variable.

To identify the factors that influence the employment status of women, multivariate analyses, such as logistic regression or factor analysis, can be conducted to identify the significant predictors of women's employment status with respect to all other relevant variables. The logistic regression model is expressed as follows:

Findings and Discussion

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 2 shows that approximately 56.92% of women aged 15-49 years are engaged in some form of employment, which is similar to the 57% of women currently employed (NDHS, 2016). Moreover, the increasing trend of women's employment has been seen over the past several years as a major indicator.

Table 2: Prevalence of working status of married women aged 15-49 years in Nepal

| Category | Weighted Frequency | Weighted Percentage |

| Not Employed “No” | 5540 | 43.08 |

| Employed “Yes” | 7322 | 56.92 |

| Total obs. (N) | 12862 | 100 |

| (Weighted Data) Percentage: 56.92% | ||

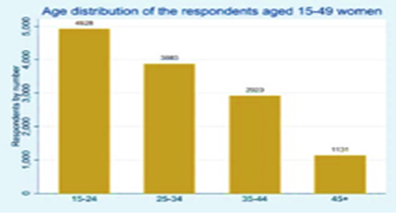

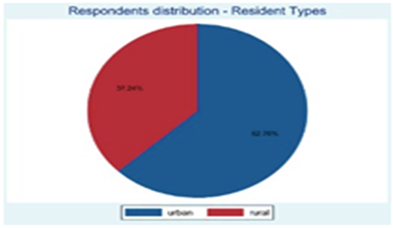

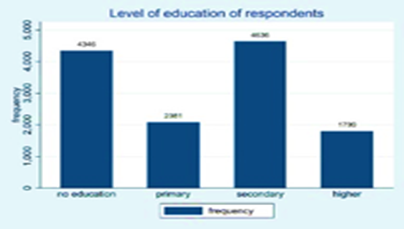

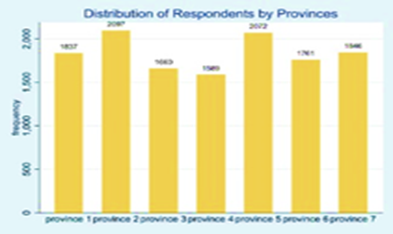

Table 3 shows the sociodemographic profile of the married women aged 15-49 years. A total of 12862 respondents were enrolled in the NDHS 2016,of whom 8866 were male and 3996 were female. This shows that, compared with females, almost 69% of households in the patriarchy group were male. The majority of respondents lived in urban areas rather than urban areas. The oldest age group of the sampled respondents was 25 to 34 years (30.64%), followed by 35 to 44 years (23.01). Thirty-five percent of the respondents had a secondary education, followed by 33% with no education. A greater number of women with 1 to 3 children were recorded, followed by no children and 4+ children. The distribution of the wealth indices was similar, ranging from poorest to richest. The respondent’s husbands had a more secondary level of education (47%). We can see that in terms of education, 33.28% of women had no education, whereas only 12% had no education. Provinces 1, 2, 3, and 5 had similar percentages of respondents enrolled in the survey, and the other three had similar percentages, but province 6 had the lowest percentage. Seventy-two percent of the married women had a phone. This section includes pie and bar charts of socio-demographic tables. This consist of Error! Reference source not found., Error! Reference source not found., Error! Reference source not found. and Error! Reference source not found. (NDHS, 2016).

Figure 1: Age distribution of respondents aged 15-49 (NDHS, 2016).

Figure 2: Respondents Resident Distribution (NDHS, 2016).

Figure 3: 1evel of education of respondents (NDHS, 2016).

Figure 4: 1evel distribution by provinces (NDHS, 2016).

Table 3: Sociodemographic profile of married women aged 15-49 years.

| Factors | Weighted Frequency | Weighted Percentage |

| Sex of Household Head | ||

| Male | 8866 | 68.93 |

| Female | 3996 | 31.07 |

| Respondents Age Group | ||

| 15-24 | 4849 | 37.70 |

| 25-34 | 3941 | 30.64 |

| 35-44 | 2960 | 23.01 |

| 45+ | 1113 | 8.65 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 8072 | 62.76 |

| Rural | 4790 | 37.24 |

| Respondent Education | ||

| No Education | 4281 | 33.28 |

| Primary | 2150 | 16.72 |

| Secondary | 4,516 | 35.11 |

| Higher | 1,915 | 14.89 |

| Children Category | ||

| No Children | 3724 | 28.95 |

| 1 to 3 Children | 7164 | 55.70 |

| 4 and More Children | 1975 | 15.35 |

| Household Wealth Index quintile | ||

| Poorest | 2176 | 16.92 |

| Poorer | 2525 | 19.63 |

| Middle | 2595 | 20.17 |

| Richer | 2765 | 21.50 |

| Richest | 2801 | 21.78 |

| Partners/Husband Education | ||

| No Education | 1575 | 12.25 |

| Primary Education | 2158 | 16.77 |

| Above Secondary Education | 6119 | 47.58 |

| Don’t Know | 3010 | 23.40 |

| Division/Provinces | ||

| province 1 | 2173 | 16.90 |

| province 2 | 2563 | 19.93 |

| province 3 | 2732 | 21.24 |

| province 4 | 1249 | 9.71 |

| province 5 | 2274 | 17.68 |

| province 6 | 724 | 5.63 |

| province 7 | 1145 | 8.91 |

| No | 3520 | 27.37 |

| Yes | 9342 | 72.63 |

| Overall | 12862 | 100 |

Bivariate analyses (chi-square test)

Table 4 illustrates the chi-square test performed to determine the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variables. The table shows that the test values are significant at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels. The two variables of sex of the household head and residence type are significant at the 10% level. Moreover, for the other explanatory variables, there exists a significant association with the current employment status of women in Nepal.

Table 4: Factors associated with women's employment status among married women aged 15-49 years in Nepal

| Variables | Employed (%) | Not Employed (%) | Chi2-value | P value |

| Sex of Household Head | 5.72 | 0.0991* | ||

| Male | 56.22 | 43.78 | ||

| Female | 58.48 | 41.52 | ||

| Respondents Age Group | 477.69 | <0> | ||

| 15-24 | 45.07 | 54.93 | ||

| 25-34 | 60.95 | 39.05 | ||

| 35-44 | 67.03 | 32.97 | ||

| 45+ | 67.44 | 32.56 | ||

| Residence | 27.52 | 0.0891* | ||

| Urban | 55.16 | 44.84 | ||

| Rural | 59.9 | 40.1 | ||

| Respondent Education | 135.58 | <0> | ||

| No Education | 62.53 | 37.47 | ||

| Primary | 60.33 | 39.67 | ||

| Secondary | 50.9 | 49.1 | ||

| Higher | 54.78 | 45.22 | ||

| Children Category | 196.43 | <0> | ||

| No Children | 47.93 | 52.07 | ||

| 1 to 3 Children | 59.27 | 40.73 | ||

| 4 and More Children | 65.37 | 34.63 | ||

| Household Wealth Index quintile | 646.12 | <0> | ||

| Poorest | 75.58 | 24.42 | ||

| Poorer | 65.98 | 34.02 | ||

| Middle | 53.93 | 46.07 | ||

| Richer | 49.58 | 50.42 | ||

| Richest | 44.29 | 55.71 | ||

| Partners/Husband Education | 103.90 | 0.0003** | ||

| No Education | 62.08 | 37.92 | ||

| Primary Education | 63.34 | 36.66 | ||

| Above Secondary Education | 56.48 | 43.52 | ||

| Don’t Know | 50.53 | 49.47 | ||

| Division/Provinces | 488.28 | <0> | ||

| Province 1 | 59.06 | 40.94 | ||

| Province 2 | 38.51 | 61.49 | ||

| Province 3 | 61.53 | 38.47 | ||

| Province 4 | 61.32 | 38.68 | ||

| Province 5 | 59.09 | 40.91 | ||

| Province 6 | 63.18 | 36.82 | ||

| Province 7 | 70.05 | 29.95 | ||

| Own a Mobile Phone | 9.70 | 0.0247** | ||

| No | 54.71 | 45.29 | ||

| Yes | 57.76 | 42.24 |

Note on CI: *** 99% confidence interval; ** 95% confidence interval; * 90% confidence interval

Logistic Regression Analysis

The unadjusted logistic regression model from Table 5 shows that households with a female as the household head have a 10% greater tendency to be engaged in employment. Among women in the 25-34, 35-44, and 45+ age groups, 1.90, 2.48, and 2.52 times the odds of being employed, respectively, were found compared to those in the 15-24 age group. This shows that the greater the age is, the greater the possibility of being engaged in any form of employment. Women residing in rural areas have 21% greater odds of being employed than women residing in urban areas. This may be because the population of rural areas is likely to perform agricultural and labor work on a daily basis. Among those with no education, 38% had 38%, and women with a primary education had a 25% greater chance of being employed than women with higher education. This is a contradictory result because many women in Nepal work as daily wage laborers compared to educated women who perform professional/official work. Nepal is a highly rural economy where farming and daily wage labor are the main economic activities for women. Agricultural land is more common in rural areas where farming and agriculture need no education. This is considered an agri-business service [3].

Women who have four or more children are 2.05 times more likely to be currently employed than women with no children are, as more children need more income to address or fulfill the daily basic needs of the family. Therefore, this might be the reason why women are engaged in some form of employment. Women from the poorest families are 3.14 times more likely to be working than women from richer families are. Married women whose partners/ husbands had a primary level of education had a 6% greater chance of being employed than women whose partners/husbands had no basic education. Women from Province 7 have a 62% greater chance of being employed than women from Province 1. Women who use mobile phones are 1.13 times more likely to be employed than women who are not using phones.

Table 5: Unadjusted logistic regression results for women's employment status in Nepal

| Variables | Odds Ratio | P value | 95% Conf. Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Sex of Household Head | ||||

| Male (Reference) | ||||

| Female | 1.10 | 0.099 | 0.98 | 1.22 |

| Respondents Age Group | ||||

| 15-24 (Reference) | ||||

| 25-34 | 1.90 | <0> | 1.69 | 2.15 |

| 35-44 | 2.48 | <0> | 2.21 | 2.78 |

| 45+ | 2.52 | <0> | 2.13 | 2.99 |

| Residence Type | ||||

| Urban (Reference) | ||||

| Rural | 1.21 | 0.089 | 0.97 | 1.52 |

| Respondent Education | ||||

| No Education | 1.38 | <0> | 1.16 | 1.63 |

| Primary | 1.25 | 0.016 | 1.04 | 1.51 |

| Secondary | 0.86 | 0.047 | 0.73 | 0.99 |

| Higher (Reference) | ||||

| Children Category | ||||

| No Children (Reference) | ||||

| 1 to 3 Children | 1.58 | <0> | 1.39 | 1.79 |

| 4 and More Children | 2.05 | <0> | 1.72 | 2.44 |

| Household Wealth Index quintile | ||||

| Richer (Reference) | ||||

| Poorest | 3.15 | <0> | 2.51 | 3.95 |

| Poorer | 1.97 | <0> | 1.68 | 2.32 |

| Middle | 1.19 | 0.011 | 1.04 | 1.36 |

| Richest | 0.81 | 0.013 | 0.68 | 0.96 |

| Partners/Husband Education | ||||

| No Education (Reference) | ||||

| Primary Education | 1.06 | 0.487 | 0.91 | 1.23 |

| Above Secondary Education | 0.79 | 0.006 | 0.67 | 0.94 |

| Don’t Know | 0.62 | <0> | 0.53 | 0.74 |

| Division/Provinces | ||||

| province 1 (Reference) | ||||

| province 2 | 0.43 | <0> | 0.31 | 0.62 |

| province 3 | 1.11 | 0.590 | 0.76 | 1.61 |

| province 4 | 1.10 | 0.602 | 0.77 | 1.57 |

| province 5 | 1.00 | 0.995 | 0.68 | 1.47 |

| province 6 | 1.19 | 0.404 | 0.79 | 1.79 |

| province 7 | 1.62 | 0.022 | 1.07 | 2.45 |

| Own a Mobile Phone | ||||

| No (Reference) | ||||

| Yes | 1.13 | 0.025 | 1.02 | 1.26 |

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

The multivariate-adjusted logistic regression model from Table 6 shows that household heads with females have a 6% lower tendency to be employed than households with a male as a head when other variables are considered constant. However, this difference was not statistically significant, as the p value was 0.279 > 0.05. The odds of being employed were 2.24 times greater for women in the 25-34 age group (AOR=2.24, 99% CI= 1.98, 2.54), 3.32 times greater for women in the 35-44 age group (AOR=3.32, 99% CI= 2.84, 3.88), and 3.36 times greater for those in the 45+ age group (AOR=3.36, 99% CI= 2.74, 4.13) than for those in the 15-24 age group when other variables were kept constant. This means that older women tend to be more employed. Women residing in rural areas have a 3% greater chance of being employed than women in urban areas. This might be because in rural areas, people are usually employed in daily waged labor.

Women with higher education levels had a 42% greater chance (AOR=1.42, 99% CI=1.14, 1.76) of being employed than noneducated women did, while the effects of all the other variables were kept constant. With no children serving as a reference, none of the variables in this category show a significant association with women's employment status. This model also predicts that the odds of women being employed from poorer families are 44% less likely (AOR=0.66, CI=0.54, 0.80) than women from the poorest family, keeping all the other variables constant. Similarly, compared with those of the poorest family, the odds of women being employed in the middle family are 56% (AOR=0.44, CI=0.35, 0.56) lower when another variable is constant. Women employed in the richer and richest wealth quintiles have 69% and 83%, respectively, lower chances than women employed by the poorest family.

The respondent partner's education is not significantly related to the employment status of women. The odds of being employed in province 2 are 52% lower (AOR=0.48, 99% CI=0.34, .070) than those in province 1 when other provinces are kept constant. Province 3 and Province 7 had 42% (AOR=1.42, CI=1, 2.02) and 47% (AOR=1.46, CI=1.00, 2.14) greater chances of being employed, respectively, than did Province 1 when other variables were kept constant. The model predicts that women who have a mobile phone have a 26% (AOR=1.26, 99% CI=1.11, 1.43) greater chance of being employed than women who have no mobile phone.

Table 6: Adjusted logistic regression results for women's employment status in Nepal

| Variables | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% Conf. Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Sex of Household Head | ||||

| Male (Reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.94 | 0.279 | 0.85 | 1.04 |

| Respondents Age Group | ||||

| 15-24 (Reference) | ||||

| 25-34 | 2.24 | <0> | 1.98 | 2.54 |

| 35-44 | 3.32 | <0> | 2.84 | 3.88 |

| 45+ | 3.36 | <0> | 2.74 | 4.13 |

| Type of Residence | ||||

| Urban (Reference) | ||||

| Rural | 1.03 | 0.747 | 0.83 | 1.29 |

| Respondent Education | ||||

| No Education (Reference) | ||||

| primary | 1.12 | 0.253 | 0.92 | 1.35 |

| secondary | 1.00 | 0.931 | 0.83 | 1.22 |

| higher | 1.42 | 0.002 | 1.14 | 1.76 |

| Children Category | ||||

| No Children (Reference) | ||||

| 1-3 Children | 1.05 | 0.579 | 0.87 | 1.26 |

| 4 and more | 0.94 | 0.619 | 0.75 | 1.18 |

| Household Wealth Index quintile | ||||

| Poorest (Reference) | ||||

| poorer | 0.66 | <0> | 0.54 | 0.80 |

| middle | 0.44 | <0> | 0.35 | 0.56 |

| richer | 0.31 | <0> | 0.24 | 0.39 |

| richest | 0.17 | <0> | 0.13 | 0.23 |

| Partners/Husband Education | ||||

| No Education (Reference) | ||||

| primary | 0.98 | 0.788 | 0.82 | 1.16 |

| above secondary | 1.05 | 0.607 | 0.87 | 1.28 |

| do not know | 1.20 | 0.144 | 0.93 | 1.54 |

| Division/Provinces | ||||

| province 1 (Reference) | ||||

| province 2 | 0.48 | <0> | 0.34 | 0.70 |

| province 3 | 1.42 | 0.045 | 1.00 | 2.02 |

| province 4 | 1.13 | 0.417 | 0.83 | 1.58 |

| province 5 | 1.17 | 0.385 | 0.82 | 1.64 |

| province 6 | 0.75 | 0.181 | 0.48 | 1.14 |

| province 7 | 1.45 | 0.053 | 0.99 | 2.12 |

| Own a Mobile Phone | ||||

| No (Reference) | ||||

| yes | 1.26 | <0> | 1.11 | 1.43 |

Summary and Conclusion

In summary, this study focused on determining the factors that may influence the employment status of women in Nepal. The summary is based on the data analysis of the NDHS 2016 data, which were financially supported by the USAID in different countries. The findings indicate that women's employment is greater than their unemployment rate, which is similar to the findings disseminated by the NDHS. The study showed that women are still far behind men in terms of employment. The findings show that women with no education are more employed than women with a professional education are; women tend to be employed in daily wage labor-based jobs that need no education for employment. The least employed women are seen in Province 6 compared to other provinces. Province 6 is the regressor province and lags far behind in infrastructure and development; various social stigmas for females are prevalent in these areas. This could also explain why they had less employment. Therefore, opportunities for women should be created with a focus on new program designs in the coming years. The age of married women is associated with employment, whereas older women are more likely to be employed. Women who had a higher education are likely to be employed .42 times more often than women with a lower education, followed by those with a primary education. However, women with secondary education and no education have similar levels of employment. The study suggested that women whose husbands’ education is above the secondary level are likely to be employed, which shows cooperation and understanding in educated couples.

The study suggests that several governments, local-level governments, prime ministers’ employment programs, NGOs, and INGOs should design and create employment opportunities to join professional job sectors. Moreover, education and employment are the most important factors in today’s context. In comparison to males, women's employment opportunities should be prioritized depending upon their education and literacy level. Moreover, for noneducated women, vocational training and skills programs can be organized by different local-level governments relating to agriculture and livestock, sewing, rearing, and farming according to relevance, which will increase independence at the local level through an increase in production.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not needed for the above study since secondary data were used and are available on the public domain DHS website.

Consent for publication

The data used for analysis are available in the public domain. Moreover, we have not used any images or details from any individual participants, and we do not need any consent for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The following data were obtained from demographic and health surveys (DHS) and are available here: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests associated with this study.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author’s Contributions

Sandesh Bhattarai contributed to the study design and conceptualization of the analysis methods. Sandesh Bhattarai and Md. Sajan Bish reviewed the literature and performed the statistical analysis. Sandesh Bhattarai formatted the table and figures to be presented in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the DHS program for providing the data.

References

- Kehinde MO, Shittu AM, Adeyonu AG, Ogunnaike MG. (2021). Women empowerment, Land Tenure and Property Rights, and household food security among smallholders in Nigeria. Agric Food Secur, 10(1):25.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Hossain M, Tisdell CA, Hossain M, Tisdell CA. (2005). Does Workforce Participation Empower Women? Micro-Level Evidence from Urban Bangladesh.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2022). World Bank Report. Nearly 2.4 Billion Women Globally Don’t Have Same Economic Rights as Men.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Dahal P, Joshi SK, Swahnberg K. (2022). A qualitative study on gender inequality and gender-based violence in Nepal. BMC Public Health, 22(1):2005.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Verick S. (2014). Female labor force participation in developing countries. IZA World Labor.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mukhopadhyay U. (2023). Disparities in Female Labor Force Participation in South Asia and Latin America: A Review. Rev Econ, 74(3):265-288.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Sarwar F, Khan REA. (2021). Factors Contributing Toward Women Employability: An Impact Assessment of a Women Skill Development Training Program. Rev Econ Dev Stud. 7(3):417-431.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Jain BK. (2020). Employment Empowering Women: An Experience of Nepal. Tribhuvan Univ J, 35(2):116-134.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2005). International Labor Office in Nepal, editor. Dalits and labor in Nepal: discrimination and forced labor. Kathmandu, Nepal: International Labor Organization, ILO in Nepal. 150.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Vinding D, Kampbel ER. (2012). Indigenous women workers: with case studies from Bangladesh, Nepal and the Americas. Geneva: ILO.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Mahmud S, Shah NM, Becker S. (2012). Measurement of Women’s Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh. World Dev, 40(3):610-619.

Publisher | Google Scholor - Ministry of Health, Nepal; New ERA; and ICF. (2017). Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health, Nepal.

Publisher | Google Scholor - (2021). The Kathmandu Post. “Wage Gap between Men and Women Persists, Report Says”.

Publisher | Google Scholor